Exhibition offers a fascinating journey into the uniqueness of Galileo

PADUA.- Nothing was ever the same again after Galileo. Not only in terms of astronomical research and science, but in art as well. With him, the sky became the realm of astronomers rather than astrologists.

For the first time ever, the exhibition conceived by Giovanni C.F. Villa for the Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Padova e Rovigo (Padua, Palazzo del Monte di Pietà, 18th November 2017 – 18th March 2018) relates the role of one of the leading characters of the Italian and European myth, outlining his figure in full. This art show, completely original in nature, brings together masterpieces of Western art and a variety of papers and artefacts that take us on a journey of discovery of a man that everyone has heard of, but few really know.

The exhibition reveals multiple facets of the “man Galileo”: from the scientist who invented the scientific method to the man of letters extolled by Italian authors and critics such as Foscolo and Leopardi, Pirandello and Ungaretti, De Sanctis and Calvino. From Galileo the virtuoso musician and performer to Galileo the artist, depicted by Erwin Panofsky as one of the leading art critics of the 1600s. From Galileo the entrepreneur – renowned for his telescope, he also designed a type of microscope (“occhiolino”) and compass – to Galileo in his everyday life. For the man proved just as extraordinary in his small vices and weaknesses as in his powerful intuition and scientific genius. Amongst other things: his studies in the field of viticulture and great love of the wine produced on the Euganean Hills – indeed, preferring to trade his precision instruments with “the best” of wines rather than to accept “filthy lucre” – or his production and sale of medicinal pills.

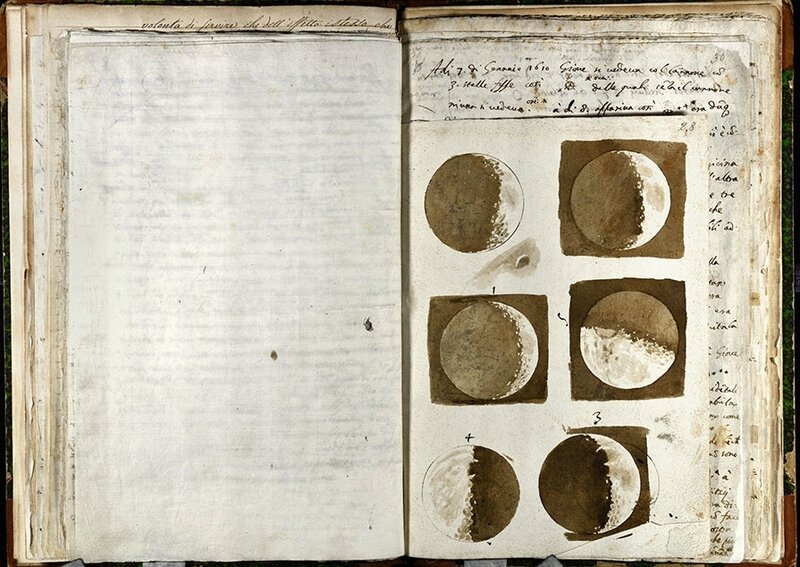

In order to supply “The Galileo Revolution” with documentary evidence, Giovanni C.F. Villa has brought an impressive amount of artwork to Palazzo del Monte di Pietà in Padua, starting from Galileo’s own magnificent watercolours and sketches, which showcase his great drawing ability. After all, the scientist was a keen observer of art, as shown by his salacious comments ranging from wood intarsias (“lacking in softness and made of sticks”) to Arcimboldo, author of “vagaries characterised by a blurry and chaotic medley of lines and colours”. The influence brought to bear by Galileo’s achievements, not to mention by modern science, on artistic culture has been recognisable since the early 1600s: from detailed depictions of nature, as attested by the stunning works by Govaerts and the Brueghel family, to a style of painting that instantly accepted the enormous impact of Galileo’s “machines”.

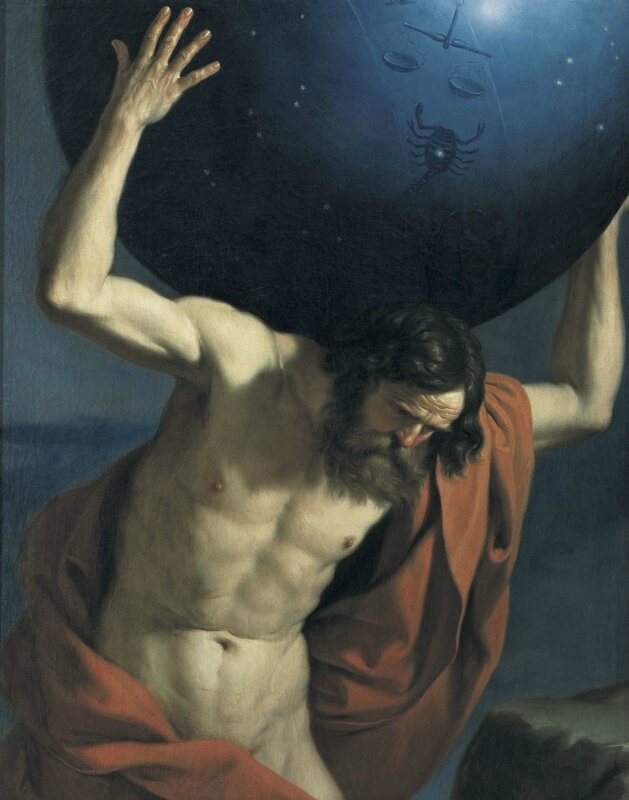

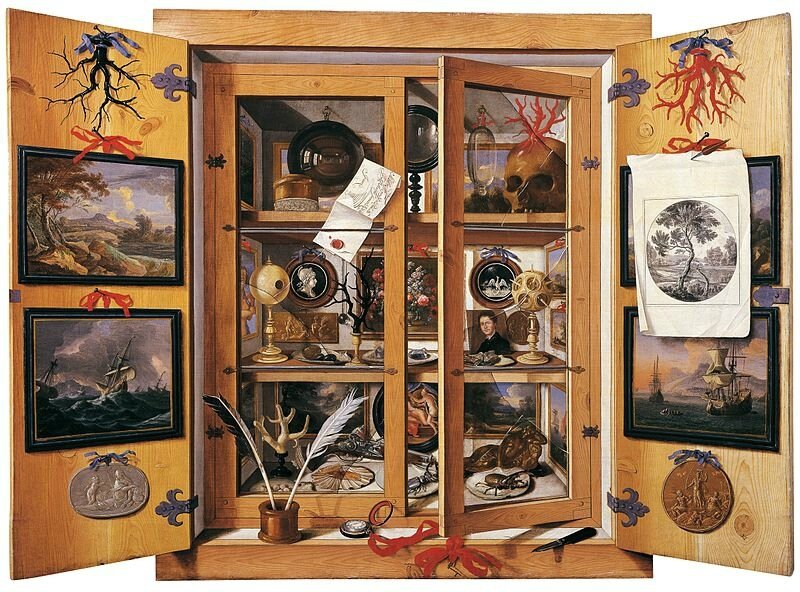

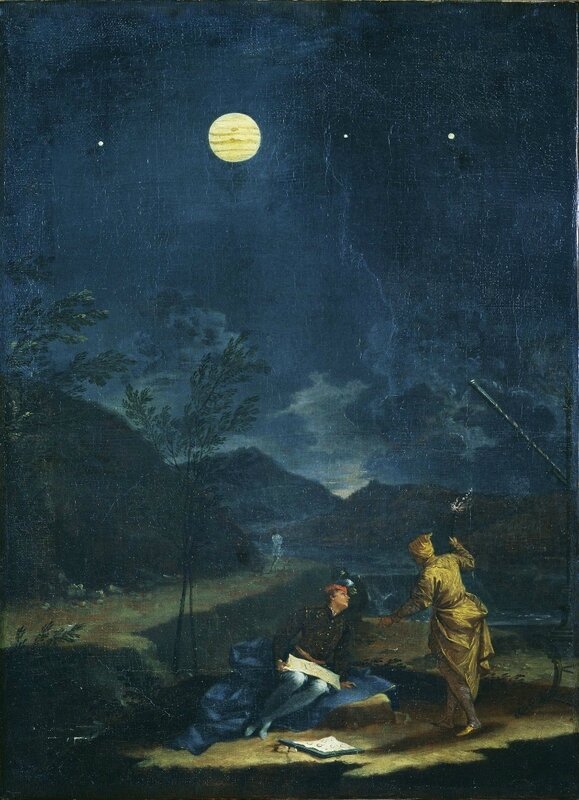

We can see the immediate effect of Galileo’s Sidereus Nuncius, published in 1610, in Adam Elsheimer’s famous Flight into Egypt, the first rendering of the Milky Way. And later, in a series of artists capable of depicting the moon as it appeared with the telescope; indeed, a major section of the exhibit is devoted to the “discovery” of the moon, from Galileo all the way down to modern times. Even the genre of the still life develops new compositional formulas, as vanitas symbols are replaced by documentary portrayals linked to the development of natural science. Followed by an iconographic story told by a series of masterpieces, amongst which Guercino’s painting devoted to the myth of Endymion stands out, alongside one of the earliest portrayals of the spyglass improved by the scientist from Pisa. The 1620s and 1630s saw the advent of a Galilean bottega or studio; that is, a generation of artists (Artemisia Gentileschi, Jacopo da Empoli, Stefano della Bella, etc.) able to share in the suggestions arising from the scientist’s precepts. For instance, Donato Creti’s Astronomical Observations, now housed in the Vatican Museums: a series of magnificent canvases depicting stars and planets as observed with a telescope, recalling Galileo’s discoveries.

Giovanni Francesco Barbieri (Guercino), Atlante, 1645-1646. © Musei Civici Fiorentini - Museo Stefano Bardini

Finally, the exhibit’s vast section devoted to contemporary art ranges from Previati and Balla to Anish Kapoor, who contributed the opening artwork.

Thus, seven centuries of Western art interweave with science, technology and Galilean hagiography to fully restore the human path of Galileo in the city – Padua – that saw him play a leading role for 18 years. Fondly remembered by the scientist as the happiest in his life due to the freedom granted to him by the Paduan Studio which, at the time, represented the pinnacle of European culture. And indeed, as announced by Rector Professor Rosario Rizzuto, the Università degli Studi di Padova itself has drawn up a programme of activities, meetings and in-depth study on the figure of one of the college’s greatest teachers and Masters of all time to coincide with the exhibition.

Galileo Galilei, Osservazioni della luna, 1609. © Central National Library - Florence.

Dialogue over the Two Maximum Systems of the World, In Fiorenza, Per Gio:Batista Landini MDCXXXII, private collection.

Luca Giordano (1634-1705), Self-portrait as astronomer. Private collection.

Domenico Remps (1620-1699), Cabinet of Curiosities, 1690s. © Museo dell'Opificio delle Pietre Dure, Florence.

Donato Creti, (Cremona 1671 - Bologna 1749), Astronomical observations, Jupiter, 1711. © Musei Vaticani

Donato Creti, (Cremona 1671 - Bologna 1749), Astronomical observations, Venus, 1711. © Musei Vaticani

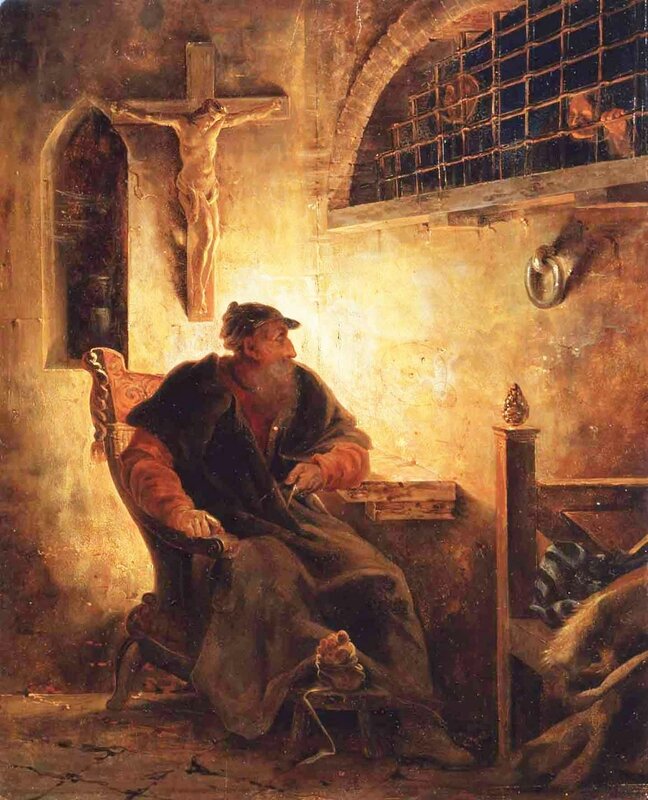

Cesare Benevello della Chiesa, Galileo in jail, before 1838. © Musei Civici, Pavia

Cristiano Banti, Galileo in front of the Inquisition, 1857. © Palazzo Foresti

Anish Kapoor, Laboratory for a New Model of the Universe, 2006, Acrylic, 123 x 134.1 x 132.7 cm. Photo Wilfried Petzi © Anish Kapoor, 2017

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F06%2F47%2F119589%2F122451614_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F08%2F32%2F119589%2F110757077_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F93%2F66%2F119589%2F75410176_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F50%2F06%2F119589%2F35567148_o.jpg)