Rarely seen seventeenth-century painting makes its North American debut at the Yale Center for British Art

Unknown artist (Dutch School), The Paston Treasure, ca. 1663, oil on canvas, Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, Norwich, UK, courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service.

NEW HAVEN, CONN.- The Yale Center for British Art presents an exhibition featuring the enigmatic masterpiece The Paston Treasure (ca. 1663) in its North American debut. Organized in partnership with the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, UK, and on view from February 15 through May 27, 2018, The Paston Treasure: Microcosm of the Known World explores the world of the Pastons—a landowning family of Norfolk famous for their medieval letters—through a display of nearly 140 objects from more than fifty international institutional and private lenders. This exhibition includes five treasures from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries that appear in the painting: a pair of silver-gilt flagons, a Strombus shell cup, two unique nautilus cups, and a perfume flask with a mother-of-pearl body, which are gathered together for the first time in more than three centuries. A host of other objects, many with Paston provenance, depict the story of collecting within the family from the medieval period until the moment of the making of the painting. This exhibition will subsequently travel to the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, where it will be on view from June 23 to September 23, 2018.

Unknown artist (English), Pair of Flagons, 1598, silver gilt, cast, chased, engraved, and pricked, Untermyer Collection, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

“This painting is about distances, geographical as well as temporal. It is a complex and highly personal representation of the world as the Pastons saw it—a world of wealth and sensuality, which for the family, was not to last,” said Nathan Flis, one of the exhibition’s organizing curators (and Head of Exhibitions and Publications, and Assistant Curator of Seventeenth-Century Paintings at the Center). Like the painting, which captures in a microcosm the world as the Pastons knew it, the individual objects take us on journeys across time and place. The late sixteenth-century silver-gilt flagon decorated with shells and dolphins is held by the young man on the left side of the painting. In his other hand, he holds a mounted Strombus shell, an exotic species from the West Indies, which is tipped on its side. He exhibits for the viewer’s contemplation the open forms of both flagon and Strombus shell cup just as he, a person with dark skin originating from a distant place, and in all probability a slave owned by the Pastons, would have been the subject of curiosity and wonder for a European audience.

Unknown artist (Dutch), Nautilus cup, ca. 1630–60, Nautilus pompilius shell, silver gilt, with auricular-style mount (original mount, but shell replaced), courtesy of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

The nautilus shells were harvested on the slopes of coral reefs in Southeast Asia (the part of the world most prominently displayed on the globe in the painting) and were then imported to the Low Countries, where they were transformed—polished to reveal their lustrous mother-of-pearl undersurfaces, which were often engraved, and their mounts shaped with mythological sea creatures. The body of the perfume flask on the far right of the painting was assembled in Gujarat from eight mother-of-pearl segments derived from the South Pacific green turban snail, and the shell flask was imported to London where it was given its metal mount and chains. All of these objects, and others in the exhibition that belonged to the Pastons, had fascinating subsequent provenances too; centuries later they found their way into the hands of collectors like the Rothschilds, J. Pierpont Morgan, and William Randolph Hearst.

Attributed to Nicolaes de Grebber, Nautilus cup, 1592, Nautilus pompilius shell, silver gilt, glass, and enamel, Collection Museum Het Prinsenhof, Delft, Acquired with the support of the Vereniging Rembrandt, courtesy of Museum Het Prinsenhof, Delft.

The Paston Treasure was commissioned around 1663 by either Sir William Paston, first Baronet (1610–1662/63), or his son Robert Paston, first Earl of Yarmouth (1631– 1683). The identity of the painter, a Dutch itinerant artist working out of a makeshift studio at Oxnead Hall, remains unresolved, although candidates have been proposed. Adding to its mystique, the painting defies categorization because it combines several art historical genres: still life, portraiture, animal painting, and allegory. It has provided the opportunity to think anew about seventeenth-century studio practice, and the painterpatron relationship.

Attributed to the workshop of Stephen Pilcherd and Anthony Hatch, Cup with strombus shell, ca. 1660, Lobatus goliath shell, brass, and enamel, Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, Norwich, UK, courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service.

“The Paston Treasure is the first painting to record accurately the richly diverse and internationally collected possessions of any English gentry family. It survives as the single most important visual document of a lost collection—that of the Paston family’s country house, Oxnead Hall in Norfolk,” said Andrew Moore, exhibition curator (and former Keeper of Art at the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery). The painting celebrates the multigenerational legacy of collecting, while providing only a glimpse of the family’s larger collection, which contained hundreds of such treasures: the seventeenth-century inventories describe dozens of mounted shells, ostrich eggs, and coconuts, in addition to pietre dure tables and cabinets, works of sculpture in bronze and marble, paintings and works on paper, books and manuscripts, gemstones, jewels, and a pair of crocodiles that hung in the hall at Oxnead.

Unknown artists (Gujarati and English), Mother-of-Pearl Flask, first half of the seventeenth century, with mounts, ca. 1650–60, mother-of-pearl from the Turbo marmoratus (assembled in Gujarat), silver gilt (mounted in London), private collection, London, photo by Jon Stokes.

Likely initiated by the Tudor sea captain Clement Paston (ca. 1515/23–1598), who built the family’s primary residence, Oxnead Hall, the collection was further augmented by subsequent generations. William Paston traveled to Italy, Egypt, Palestine, and Jerusalem from 1638 to 1639 and returned to Oxnead with fascinating treasures from his world tour. A poem dedicated posthumously to Sir William, discovered among the Sloane manuscripts in the British Library in the course of research for the exhibition, celebrates his voyage and suggests the image of a restless spirit who continues his travels:

“There is lacking in his treasure-house this one unique and everlasting gem: it is called eternal life. To purchase this, he sails under Christ’s auspices, to the market of the new Jerusalem.” In the crescendo moment of this exhibition, the “best closet” at Oxnead is partially reconstructed with a dense display of decorative arts objects, elaborate vessels, jewels, natural history specimens, musical instruments, and sculptures interspersed with paintings, miniatures, and drawings.

Unknown artist (Florentine), Pietre dure tabletop, ca. 1625, with coats of arms, 1638, stone inlay, including lapis lazuli, red jasper, agate, and chalcedony, on a ground of black Belgian marble, private collection.

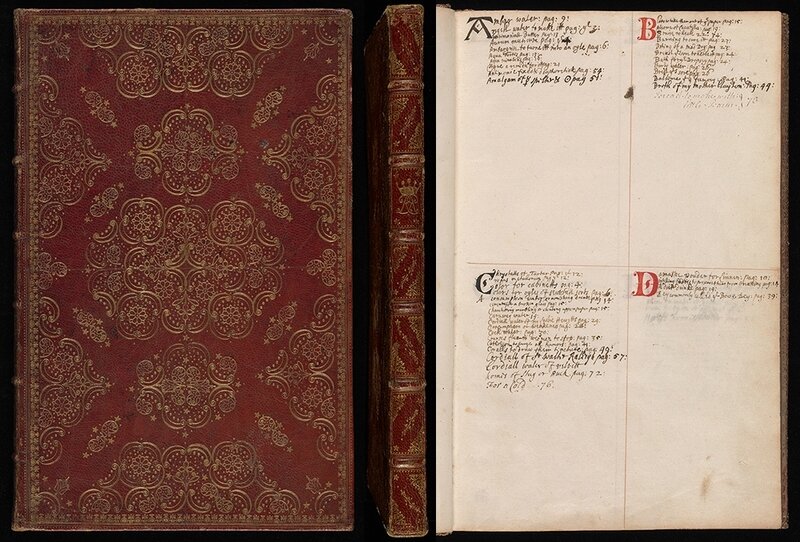

The final section of the exhibition re-creates Sir Robert Paston’s alchemical laboratory. An early member of the Royal Society and contemporary of Isaac Newton (1643–1727), “Sir Robert had an obsession for alchemy, particularly the imitation of natural substances, the production of painters’ pigments, and the search for the philosopher’s stone, or red elixir, a legendary substance capable of transmuting base metals into precious ones,” said Francesca Vanke, organizing curator (and Keeper of Art and Curator of Decorative Art at the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery). Robert’s book of alchemical recipes, on loan from the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University, is displayed alongside an Italian book of primarily medical recipes that belonged to his eldest child, Margaret Paston (1652–ca. 1723). Margaret assisted in her father’s laboratory as a girl and is believed to be depicted in The Paston Treasure. She immigrated to Venice in the 1670s and established her own alchemical workshop, specializing in pharmacology.

Attributed to the Master of The Paston Treasure, Monkeys and Parrots, ca. 1660s, oil on canvas, Collection of Glen Dooley, New York.

Despite financial difficulties brought on by the English Civil War (1642–51), when their estates were sequestered by Oliver Cromwell’s (1599–1658) army, the Pastons continued to spend lavishly, their obsessive collecting leading to the point of ruin. Robert failed to transmute base metals into precious ones, and the family fortunes continued to decline. The collection was sold off within two generations of the painting’s completion, resulting in the worldwide dispersal of the treasures the organizers have regathered for this display. “The painting speaks to themes of wealth, continuity, knowledge, transformation, ambition, alchemy, survival and loss, and ultimately, a sad demise,” said Edward Town, co-organizing curator (and Head of Information Access, and Assistant Curator of Early Modern Art at the Center).

Unknown taxidermist, Nile crocodile(Crocodylus niloticus), mid-twentieth century, Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

Questions about the nature of The Paston Treasure itself—including who painted it and for what purpose—lie at the heart of this exhibition. Between 2005 and 2006, technical analysis was undertaken by Spike Bucklow, Reader in Material Culture, Cambridge University, with Jessica David, Senior Conservator of Paintings at the Center. Their examination included conventional X-ray, which revealed a spectacular series of pentimenti in the upper-right corner of the painting: a large silver dish originally incorporated in the composition was painted over with an (unidentified) lady, which was once more painted over with the quiet solution of the diamond-shaped clock. In April 2016, lingering questions about the structure of the painting and improvements in analytical tools led the Center and the Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, in collaboration with the University of Catania, Sicily, to conduct a new campaign of stateof-the art technical analysis that revealed marked color transformation and fading in some parts of the painting, uncovering, to a certain degree, what The Paston Treasure looked like when it was fresh from the easel. The analysis also shed new light into the order in which parts of the composition were painted, as well as an unusually high number of pigment ingredients compared to contemporary still-life works. A film created for the exhibition, entitled The Paston Treasure: A Painting Like No Other, distills this data, helping audiences to understand how the painting was made and elucidating how the new research is invaluable in answering some of the riddles that have puzzled generations of scholars regarding the authorship and making of this strange and fascinating picture.

Attributed to the Master of the Legend of the Magdalen (Flemish), The Seven Sorrows of the Virgin Mary or The Ashwellthorpe Triptych, ca. 1519, Norwich Castle Museum & Art Gallery, Norwich, UK, courtesy of Norfolk Museums Service.

Castrucci workshop, Collector’s cabinet, ca. 1610, Macassar ebony with ebonized and gilded wood, and pietre dure, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Gilbert Collection.

Josias Jolly, Enamel-cased watch, ca. 1635–42, gold, enamel, gilt brass, steel, and glass, Collection of Simon Bull, England.

Unknown maker, Bass viol, ca. 1640–65, maple, spruce, and gut, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Unknown artist, Medusa cameo ring, ca. 1580, white agate set in gold and enamel, Victoria and Albert Museum, London, Salting Bequest.

Recipe book containing medical, chemical, and household recipes and formulas, ca. 1659–83, by Robert Paston, first Earl of Yarmouth (1631–1683), James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection and the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

Unknown artist (Dutch), Sir William Paston, ca. 1643–44, oil on canvas, Felbrigg Hall, The Windham Collection (National Trust). Photo: Ronnie Rysz / YCBA

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_ac5c4c_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_709b64_304-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_22f67e_303-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240417%2Fob_9708e8_telechargement.jpg)