Exhibition at the Prado Museum brings together 82 sketches by Peter Paul Rubens

Rubens, Prometheus, 1636 - 1637. Oil on panel. 16,6 x 25,7 cm, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado

MADRID.- In addition to focusing on the importance of Rubens within the history of the oil sketch and facilitating an appreciation of the unique qualities of his works of this type, the exhibition Rubens. Painter of Sketches presents the results of an exhaustive research project directed by the exhibition’s two curators: Friso Lammertse, curator of Old Master Painting at the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, and Alejandro Vergara, chief curator of Flemish and Northern schools painting at the Museo del Prado. The conclusions of their study are presented in the exhibition and also form the basis of the accompanying publication.

The practice of producing oil sketches within the process of creating a painting began in 16th-century Italy. Artists such as Polidoro da Caravaggio, Beccafumi, Federico Barrocci, Tintoretto and Veronese were the first to make use of painted oil sketches as vehicles to try out their ideas when devising a painting. However, their use of such works was limited, given that drawing was their principal preparatory method.

Rubens, The Capture of Samson, ca. 1609 - 1610. Oil on panel, 50.4 x 66.4 cm, Chicago, Art Institute of Chicago, Robert A. Waller Memorial Fund, inv 1923.551.

Basing himself on these precedents, Rubens’s innovative contribution consisted of developing this preparatory process and making systematic use of images painted in oil and on more durable supports than paper. Rubens used some of these sketches to elaborate his ideas on new compositions, or often to show to clients or as a guide for his assistants and collaborators. Depending on their different purposes, these sketches could be very sketchy or highly finished, as well as small or relatively large. They differ from the rest of the artist’s pictorial output in that they are less highly finished and detailed, the paint layer is thinner and the preparatory layer is frequently visible.

Rubens thus transformed the oil sketch into a fundamental part of his creative process, and the nearly 500 surviving examples by his hand reveal him to be the most important artist of this type of work in the history of European art.

Rubens, The Miraculous Draught of Fishes, ca. 1610. Oil on panel, 39.7 x 48.2 cm, Cologne, Wallraf-Richartz Museum & Fondation Corboud.

The present exhibition brings together 73 examples, including five small sketches for the ceiling paintings in the Jesuit church in Antwerp, loaned by the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (2), the Boijmans Van Beuningen Museum, the Národni Gallery, Prague, and the Gemäldegalerie, Vienna; the Achilles Series, the display of which is completed in the Prado’s Central Gallery of the Villanueva Building with an oil sketch from the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, shown alongside the painting of Achilles revealed by Ulysses and Diomedes by Rubens and his studio; and the Eucharist Series from the Prado’s own collection, accompanied by an oil sketch loaned from the Art Institute of Chicago. The six oil sketches in the Prado from the Eucharist Series were the subject of an important restoration project in 2014. The results were presented to the public in the exhibition Rubens. The Triumph of the Eucharist as part of the Museum’s Restoration Programme sponsored by Fundación Iberdrola.

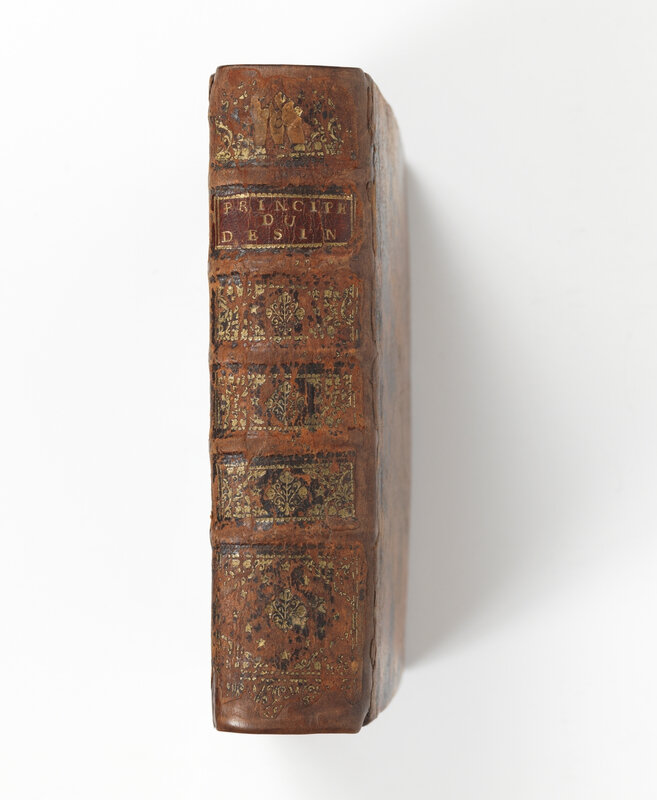

Also on public display for the first time is a manuscript copy of a lost sketchbook by Rubens known as the Bordes Manuscript which includes texts and drawings. It is the most important of the four known copies of the manuscript, which in addition to being a direct copy of the original contains two original drawings by the artist, one of them a study for the colossal sculpture known as the Farnese Hercules. The notebook entered the collection of the Prado in 2015 as a generous donation by the sculptor, architect and art historian Juan Bordes.

Anónimo (Taller de Rubens, Pedro Pablo), Manuscrito de principios artísticos de Rubens (Manuscrito Bordes), 17th century. Pencil on paper, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado

Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640) was the most important creator of oil sketches within the history of European art. Following in the footsteps of a few earlier painters from Antwerp and Italy, he painted around 500 works of this type during his career.

In the present exhibition, an “oil sketch” or simply “sketch” refers to “a painting executed in preparation for another work”. Some of these sketches were made by Rubens in order to work out ideas for new compositions, or frequently to be shown to clients or as guides for his collaborators, or often for all three purposes. According to their function they are very sketchy or highly finished and may be small or relatively large.

Rubens, Saint Matthew, 1610 - 1612. Oil on panel, 106.5 x 82 cm © Museo Nacional del Prado.

Painters prior to Rubens had primarily used drawing to prepare their works, and this was also true in his case. His innovative contribution lay in developing this preparatory process to systematically include images painted in oil and on more durable supports than paper. While drawings were normally monochrome, Rubens’s oil sketches almost always involve colour, generating the illusion of skin and muscle on the figures. The particular function of these sketches differentiates them from the rest of his pictorial output: they are less highly finished and detailed, the paint layer is thinner and the preparatory layer is often visible.

Despite their unique nature, Rubens’s oil sketches encourage the viewer to appreciate the qualities fundamental to all his art. The dynamic but light brushstroke and a sense of compressed energy convey a seriousness of purpose allied to his unique joie de vivre. Paradoxically, it is also evident that extremely important issues are resolved in these scenes, and the viewer experiences a sense of closeness to the emotions expressed in them, in the manner of a direct experience: an affirmation of what it is to be alive.

Rubens, Descent from the Cross, ca. 1611 - 1612. Oil on panel, 115.2 x 76.2 cm, London, The Courtauld Gallery, The Samuel Courtauld Trust.

The Eucharist Series

In the first half of the 1620s Rubens designed twenty tapestries on The Triumph of the Eucharist. They were commissioned by the Infanta Isabel Clara for the convent of the Descalzas Reales in Madrid and their subject is the Eucharist, the principal dogma defended by the Archduchess as Governor of the Southern Low Countries.

This large series involved the participation of Rubens, his assistants, the Infanta and the tapestry weavers. Rubens produced two series of preparatory oil sketches of different sizes.

The exhibition includes one sketch from the smaller series, the only one that shows a number of the intended tapestries in a single image (Art Institute of Chicago), and six from the larger series which belongs to the Prado. Rubens used his oil sketches to define the composition and to show to his patrons, while they also functioned as guides for his assistants, who were entrusted with painting the large-format cartoons to be used as models by the tapestry weavers.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Victory of Truth over Heresy, ca. 1625. Oil on panel, 64.5 x 90.5 cm, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Victory of Truth over Idolatry, ca. 1625. Oil on panel, 65 x 91 cm, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Defenders of the Eucharist, ca. 1625. Oil on panel, 65.5 x 68 cm, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Meeting of Abraham and Melchizedek, ca. 1625. Oil on panel, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. © Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Triumph of the Church, ca. 1625. Oil on panel, 63.5 x 105 cm, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. © Museo Nacional del Prado

Peter Paul Rubens, The Triumph of the Church, ca. 1625. Oil on panel, 65 x 91 cm, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. © Museo Nacional del Prado

Peter Paul Rubens, The Triumph of Divine Love, ca. 1625. Oil on panel, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. © Museo Nacional del Prado

Paintings for the ceiling of the Jesuit church in Antwerp

In 1620 the Jesuits commissioned Rubens to execute 39 works for the Company’s church in Antwerp. Most were to be installed on the ceiling and would thus be seen from below. The final paintings, which were destroyed in a fire in 1718, were painted by Van Dyck and other assistants. To prepare this cycle Rubens produced small monochrome sketches and other, more elaborate coloured ones, both in oil, as well as various drawings. The complicated foreshortenings required a rigorous preparatory process. The smaller sketches are studies of light and shade while the large ones indicate that the colour is already completely devised. In the accompanying contract Rubens was given the choice of handing over the preparatory sketches or of painting another work for one of the lateral altars. It would seem that he opted for the latter, indicating the esteem in which he held his own oil sketches.

The Achilles Series

The Achilles Series was the final tapestry series designed by Rubens. It depicts various episodes from the life of the Greek hero in eight scenes. Rubens prepared the project with two sets of oil sketches. The ones in the first series are smaller and less highly finished, and three of them are included in this section of the exhibition. The larger and more detailed ones from the second series were the models to be used by the weavers for painting the cartoons.

This section is completed in the Central Gallery of the Villanueva Building with the display of an oil sketch loaned by the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, shown alongside Achilles revealed by Ulysses and Diomedes by Rubens and his studio from the Prado’s own collection.

Rubens (and workshop), Achilles discovered among the daughters of Lycomedes, 1630-1635. Oil on panel, 107,5 x 145,5 cm, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. © Museo Nacional del Prado

Peter Paul Rubens, Thetis Dipping the Infant Achilles into the River Styx, ca. 1635. Oil on panel, 44.1 x 38.4 cm, Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen.

Paintings for the Banqueting House ceiling

Rubens painted these oil sketches in preparation for the painted decoration of the ceiling in the Banqueting House (part of Whitehall Palace in London), of which the subject is a celebration of the reign of James I. The sketches include the nine scenes that appear in the ceiling, in addition to various isolated figures and architectural elements.

The scene that depicts the union of the crowns of England and Scotland commemorates the most important event in the reign of James I. Here the personifications of the two nations are united by Cupid, representing Love, with Minerva above him joining the two crowns together. In the second scene Peace embraces Abundance, while in the third a figure representing both Temperance and Modesty subjugates a Vice that is identified is Immodesty in the accompanying iconographic programme.

Rubens, England, Scotland, Minerva, Cupid and Two Victories, c. 1632. Oil on panel, 64 x 49 cm, Róterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen.

Oil sketches for the Torre de la Parada

In 1636 Philip IV commissioned the now elderly Rubens to paint more than 60 mythological scenes to decorate a hunting pavilion known as the Torre de la Parada on the outskirts of Madrid. The artist designed all the scenes in small oil sketches, only painting a few of the final works himself and entrusting the execution of most of them to other painters.

The richness of Rubens’s pictorial vocabulary and his vivid imagination is evident in these sketches, which are rapidly painted with little pigment. They clearly reveal his creative process: the thin preparatory layer that functions as a base and the frequent use of vertical, black lines which help to place the figures in the composition. Other smaller lines and incised marks along the edges of the panels relate to the transfer of these small images to the final, large-format works.

Rubens, The Lion Hunt, c. 1615. Oil on panel, 73.6 x 105.4 cm, London, The National Gallery.

Domenico Tintoretto, Prayer in the garden, late 16th-first third 17th century. Gouache, tempera on paper, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paim Rubens, Franz Snyders, The Recognition of Phililpoemen, ca. 1609. Oil on canvas, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. © Museo Nacional del Prado

Peter Paul Rubens, The Recognition of Phililpoemen, ca. 1609-1610. Oil on panel, 50 x 66 cm, Paris, Musée du Louvre, Département des Peintures, Legs Dr Louis La Caze, 1869.

Peter Paul Rubens and Franz Snyders, Ceres and Two Nymphs, 1615 - 1617. Oil on canvas, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, Portrait of Clara Serena Rubens, ca. 1616. Oil on canvas, mounted on wood, 33 x 26 cm, Liechtenstein, The Princely Collections, Vaduz-Viena.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Death of the Consul Decius, 1616 - 1617. Oil on panel, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, Achilles discovered by Ulysses and Diomedes, 1616 - 1617. Oil on canvas, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Expulsion of Adam and Eve from the Garden of Eden, 1620. Oil on panel, 49.5 x 64.5 cm, Prague, Národní Galerie.

Paul Pontius (Engraver) and Peter Paul Rubens, Allegorical Portrait of the Count-Duke of Olivares, 1626. Taille douce: etching and engraving on laid paper, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. © Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, Apollo and the Python, 1636 - 1637. Oil on panel, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, Deucalion and Pyrrha, 1636 - 1637. Oil on panel, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, Hercules and Cerberus, 1636 - 1637. Oil on panel, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, Vertumnus and Pomona, 1636 - 1637. Oil on panel, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Rape of Europe, 1636 - 1637. Oil on panel, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Persecution of the Harpies, 1636 - 1637. Oil on panel, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, Cephalus and Procris, 1636 - 1637. Oil on panel, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, The Death of Hyancinth, 1636 - 1637. Oil on panel, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Peter Paul Rubens, Diana and her Nymphs Hunting, 1636 - 1637. Oil on oak panel, 27.7 x 58 cm, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

Jan Cossiers, Prometheus, 1636 - 1638. Oil on canvas, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado

Peter Paul Rubens, The Triumphal Chariot of Kallo, 1638. Oil on panel, 105.5 x 73 cm, Antwerpen, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten.

Anonymous, The Wrestlers, 18th century. Serpentine, Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado. ©Museo Nacional del Prado.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F14%2F49%2F119589%2F72525263_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F75%2F12%2F119589%2F33618667_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F52%2F119589%2F32465808_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F37%2F96%2F119589%2F30153749_o.jpg)