Very Rare Archaic Bronzes Lead Bonhams Fine Chinese Art Sale in London

© Bonhams 2001-2018

LONDON - Bonhams is delighted to offer an exceptional selection of Chinese ceramics and works of art, for sale on 17 May 2018 at New Bond St, London. The highlights include rare works of art ranging from archaic bronzes, early ceramics and later porcelain, Buddhist stone sculptures, Buddhist and Daoist bronze figures to jade, Imperial silk textiles, Imperial lacquer wares and coromandel screens. Many of the objects boast important collection provenance, including from a Royal Collection, Lord Cunliffe, Marchese and Marchesa Taliani di Marchio, Marquesa de Sotomayor y Condesa de Alba Real, C.T. Loo, T.T. Tsui, Audrey B. Love, Maurice and Marguerite Sulzbach, Stanley Charles Nott, the Mengdiexuan Collection, the Reid Collection, and many other important collectors.

Leading the sale are two very rare archaic ritual bronze vessels: A very rare archaic bronze ritual food vessel, fangding, late Shang/early Western Zhou dynasty, from the Mengdiexuan Collection, estimated at £120,000-150,000 (Lot 36); and a very rare archaic bronze ritual food vessel, ding, late Shang dynasty, 12th/11th century BC, which is estimated at £180,000-240,000, from the Reid Collection (Lot 31). Both vessels have been exhibited in important museums. Additionally, a rare archaic bronze wine vessel and cover, He, Warring States Period, estimated at £80,000-120,000 (Lot 34) will also be offered. This outstanding vessel with an unusual hinged beak mythical-bird spout, elaborately ornamented with zoomorphic motifs, is typical of Western Zhou bronzes from the South.

Lot 36. A very rare archaic bronze ritual food vessel, Fangding, Late Shang-early Western Zhou Dynasty, inscribed Zhu Fu Ding; 26.2cm (10 1/4in) high. Estimate £ 120,000 - 150,000 (€ 140,000 - 170,000). Sold for £ 368,750 (€ 422,152) inc. premium. © Bonhams 2001-2018

Crisply cast in rectangular section supported on four straight legs decorated with cicada blades, the body cast with taotie masks in relief below pairs of confronted kuidragons, all reserved on a leiwen ground, centred and flanked at the edges with flanges, the top rim set with a pair of upright loop handles, the interior cast with a two-character inscription, with olive and light green patina and malachite encrustations.

Provenance: The Mengdiexuan Collection.

Exhibited: Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong & Urban Council of Hong Kong, Ancient Chinese and Ordos Bronzes, 12 October - 2 December 1990

Hong Kong Museum of Art, Metal, Wood, Water, Fire and Earth: Gems of Antiquities Collections in Hong Kong, 21 September 2001 - 5 October 2005

Chinese University Hong Kong Art Museum, Divine Power: The Dragon in Chinese Art, 12 February - 7 November 2012.

Published and Illustrated: J.Rawson and E.Bunker, Ancient Chinese and Ordos Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1990, p.98, no.19

Metal, Wood, Water, Fire and Earth: Gems of Antiquities Collections in Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2004, p.104

Note: A related archaic bronze vessel, zun, early Western Zhou dynasty, in the Hirota Hiroshi Collection, Tokyo, cast with an identical inscription reading 'Zhu Fu Ding', is recorded by the Institute of History and Philology, Academia Sinica, Taipei, in the Digital Archives of Bronze Images and Inscriptions, no.05639.

Fangding are among the scarcest ritual vessels of the Bronze Age, and the present piece with its powerful taotie mask comprising kui dragons and robust shape is a rare example. Food vessels of square ding form were first produced in pottery as food containers in the Erlitou period and were later made in bronze in the Erligang period. In the Shang and Western Zhou dynasties, fangding were made for use in ancestral worship or other sacrificial ceremonies, and their ownership appears to have been strictly regulated; Li Xixing in The Shaanxi Bronzes, Xi'an, 1994, p.35, notes that in the Western Zhou period, the gentry were allowed to acquire three ding, high-ranking officers five, dukes seven, and the Emperor nine.

Compare a very similar, but larger (29.6cm high) fangding, Shang dynasty, from the Qing Court Collection in the Collections of the Palace Museum: Bronzes, Beijing, 2007, p.29, no.12. For other similar examples from important museum and private collections, see one dated to the late Anyang period/ early Western Zhou dynasty, illustrated in Shang Ritual Bronzes in the National Palace Museum Collection, Taipei, 1998, pp.564-569, no.97; and another illustrated by B.Karlgren, 'Some Bronzes in the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities', published in The Bulletin of the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm, 1949, no.21, pp.1-2, pl.1. A further example, from the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, is illustrated by R.L.d'Argence, Bronze Vessels of Ancient China in the Avery Brundage Collection, San Francisco, 1977, pp.74-75, pl.29; and compare also another illustrated by Takayasu Higuchi and Minao Hayashi, ed., Ancient Chinese Bronzes in the Sakamoto Collection, Tokyo, 2002, pl.108.

Compare with a similar but smaller (22.8cm high) fangding, Late Shang/ early Western Zhou dynasty, which was sold at Bonhams Hong Kong, 29 November 2016, lot 27.

Lot 31. A very rare archaic bronze ritual food vessel, Ding, Late Shang Dynasty, 12th-11th century BC, inscribed Yu ; 21cm (8 2/8in) high. (2). Estimate £ 180,000 - 240,000 (€ 210,000 - 270,000). Sold for £ 212,500 (€ 243,274) inc. premium. © Bonhams 2001-2018

The deep round body flanked by two upright loop handles and supported on three cylindrical legs, crisply cast on the sides with three taotie masks intersected by flanges, each with prominent eyes, upright horns and small claws, beneath a band of twelve stylised kuidragons on a leiwen ground, the wall of the interior cast with a pictogram, the bronze covered with an attractive olive patina with areas of encrustation, Japanese wood box.

Provenance: J.T.Tai & Co., New York

William Bowmore, Australia (1909 - 2008)

Mossgreen, Melbourne, 25 November 2008, lot 762

The Reid Collection.

Exhibited: Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide, 2 November 1999 - 1 April 2000, The William Bowmore Collection: The Fine Art of Giving. 90 Masterpieces

Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, January 2009 - February 2018 (on loan).

Note: Ritual bronze vessels such as the present lot were among the most highly prized and technically sophisticated objects manufactured in early China. Reserved for use by the most powerful families of the time, they carried the offerings presented to the ancestors during the performance of elaborate rituals. The role of these vessels was thus fundamental in ensuring the continuity of family lines, as it was believed that the ancestors were active participants to the life of their living offspring, which they could positively influence if provided with continuous nourishment.

Compare with a similar archaic bronze ding vessel, 11th-11th century BC, decorated in two registers with confronted dragons and taotie masks, illustrated by R.Bagley, Shang Ritual Bronzes in the Arthur M.Sackler Collections, pp.464-465, no.86.

An archaic bronze ding, late Shang dynasty, similarly decorated in two registers depicting dragons and taotie designs, was sold at Christie's Hong Kong, 30 May 2012, lot 4131.

Lot 34. A very rare archaic bronze wine vessel and cover, he, Warring States Period (475-221 BC); 25.5cm (10in) wide. (2). Estimate £ 80,000 - 120,000 (€ 91,000 - 140,000). Sold for £ 100,000 (€ 114,481) inc. premium. © Bonhams 2001-2018

The compressed globular body decorated around the exterior with stylised scrolling dragons on a dotted ground between two bands of C-scrolls and whorl-patterns, issuing a mythical bird-shaped spout with hinged beak, supported by three humanoid figures beneath birds with outstretched wings and curled beaks, openwork overhead beast handle linked to the flat cylindrical cover, fitted box.

Christie's Hong Kong,The Jinggutang Collection: Magnificent Chinese Works of Art, 3 November 1996, lot 597

An Asian private collection.

This vessel is unusual because of the hinged beak of the mythical bird spout. Among the bronze he of the Western Zhou period, those from southern sites are usually more elaborately ornamented with zoomorphic motifs and complex flanged elements than their northern counterparts. In the Eastern Zhou period, he from the south continue to exhibit elaborate ornamentation. Compare with a he probably from the south with similar bird-head spout, bail handle in feline form, the legs also with birds standing on the shoulders of human figures, in the Art Institute of Chicago (ac.no.1930.366), illustrated by J.So, Eastern Zhou Ritual Bronzes from the Arthur M.Sackler Collections, New York, 1995, p.411, fig.84.3.

Compare with a related tripod wine vessel and cover with bird spout, Warring States Period, illustrated by J.So, Ibid., pp.406, no.84. Another related bronze he with bird-head spout and feline form handle, early Warring States Period, is illustrated by W.Tao, Chinese Bronzes from the Meiyintang Collection, London, 2009, pp.52-53, no.24. See also another he, Warring States period, in Bronzes in the Palace Museum, Beijing, 1999, pp.286-287, no.285. Further related examples of archaic bronze tripod wine vessels, Warring States Period, are illustrated by A.J.Koop, Early Chinese Bronzes, London, 1924, pp.39 and 105. Another related vessel, Warring States, is illustrated by W.Perceval Yetts, The Cull Chinese Bronzes, London, 1939, pl.XXII, no.17.

A very rare pair of monumental fahua Buddhist lions on stands, Late Ming Dynasty, 16th/17th century, measuring over 2 metres high, are estimated at £150,000 - 250,000 (Lot 70). This outstanding pair belongs to a specially commissioned statuary group that served as guardians, most likely for an important temple. Very few related sculptures of such massive proportions have survived, making this pair exceptionally rare. They were formerly in the collection of Audrey B. Love, a philanthropist and patron of the arts, and the daughter of Edith Guggenheim and Admiral Louis Josephthal, and were previously with the eminent Chinese art dealer C.T. Loo.

Lot 70. A very rare pair of monumental fahua Buddhist lions on stands, Late Ming Dynasty, 16th-17th century; 203.3cm (80in) high overall. Estimate £ 150,000 - 250,000 (€ 170,000 - 290,000). Sold for £ 512,750 (€ 587,006) inc. premium. © Bonhams 2001-2018

The imposing pair, each superbly modelled as male and female beasts seated on their haunches with wide bulging eyes and wide gaping mouth, wearing a tassel-hung collar around the neck, the mane, thighs and flames issuing from the powerful body glazed amber, the female with the right forepaw over a playful cub, the male with the left forepaw over a brocade ball, both creatures resting on a square and waisted lotus base elaborately carved with bands of peony scrolls, petal lappets and ruyi, the central constricted section decorated with a rabbit, deer, recumbent cow and qilin, the lower section of one base a wood replacement and painted to match. (4)

Provenance: Collection of the grandson of the Daoguang Emperor, by repute C.T.Loo & Co. (labels)

Cornelius Ruxton Love Jr. (1904 - 1971) and Audrey B. Love (1903 - 2003), New York

Christie's New York, The C. Ruxton and Audrey B. Love Collection, 20 October 2004, lot 317

A distinguished Western private collection.

C. T. Loo (1880 - 1957)

Note: Audrey B. Love, a philanthropist and patron of the arts, was the daughter of Edith Guggenheim and Admiral Louis Josephthal. C. Ruxton Love Jr. was a partner with the Stock Exchange firm of Josephtal & Co. Both were well known art collectors and their collection of Napoleonic art was exhibited in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1978 and their Georgian silver collection was exhibited in the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2002. Audrey Love was a founding member of the Lowe Art Museum of the University of Miami.

This outstanding pair of Buddhist lions belongs to a specially commissioned statuary group that served as guardians, and was most likely specially commissioned for an important temple. Few related sculptures of such massive proportions have survived, making this pair exceptionally rare. Such sculptures would have probably been placed outdoors, either entirely or within a protective shelter; furthermore, the massive size and complexity of the stoneware sectional structure, are all elements which would have made such sculptures more susceptible to damage, resulting in few surviving sculptures.

Compare, however, a very similar pair of monumental fahua Buddhist lions, Ming dynasty, in the Newark Museum, New Jersey, acc.no. 39.430.1-2. This pair of lions is remarkably similar to the present lot, and was most likely made in the same workshop. Furthermore, the close similarity suggests that both pairs may have originated in the same temple or complex. The Newark Museum lions were gifted to the museum in 1939 by Herman A.E. Jaehne and Paul C. Jaehne. The present lions bear C.T.Loo labels, who was active in the US from 1915 to 1950. It is therefore likely that both pairs of lions reached the US prior to 1939, and were both possibly sold by C.T.Loo. in New York. Models of lions were introduced to China from Central Asia as symbols of religious might, but have evolved to be seen as noble and divine creatures and protectors of the Truth. Typically modelled in pairs of a male and female lion, they also symbolise the yin and yang forces, as well as the auspicious wishes for unity and continuity.

Compare also another pair of large lions, 16th century, glazed in a sancai palette, illustrated by Y.L d'Argencé, ed., Chinese, Korean and Japanese Sculpture in the Avery Brundage Collection, Japan, 1974, pp.320-321, no.171. See also a related but smaller pair of Buddhist lions on pedestals, with a temple dedicatory inscription dated to 1465 (61cm high), which was sold at Christie's London 31 March 1969, illustrated by A.du Boulay, Christie's Pictorial History of Chinese Ceramics, Oxford, 1984, p.180, no.2.

These splendid guardian lions should be visualised standing protectively before a classical temple-hall for which they were commissioned. Glazed in a striking azure blue flecked with turquoise and highlighted in yellow, they stand impressively tall, raised on waisted pedestals to an overall height of over 200 cm (80in), well over head-height. They are boldly modelled with authoritative but lively facial demeanour which masks their robust form.

Guardian figures are thought to have arrived in China from Central Asia in the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD) to be placed outside the palace halls of the wealthy. Later, with the establishment of religious sites, some of which had originated as the gifted residences of wealthy patrons, guardian figures and guardian animals continued to ward off evil at the entrances of temples and halls bequeathed or endowed anew by wealthy patrons. Most guardian figures placed in the open were lions, either carved in stone or cast in bronze or iron, and they became a fashionable sign of prestigious rank outside fine residences or generously-endowed temples. However, ceramic guardian lions are relatively few, possibly because their inherent fragility reduced the numbers which survived, and being outdoors they would be more vulnerable in turbulent times (see Fig.1 in the printed catalogue for other typical guardian figures).

Fig.1.

This pair has survived remarkably well and each assembly is presented imposingly in three parts with the lion resting on a matching two-piece pedestal 90 cm (36 in) high. They announce in many ways their Buddhist association.

The male lion, traditionally positioned on the right as one faces the hall, sits open-mouthed and staring ahead with his left front paw, as is customary, resting playfully on an embroidered brocade ball. The female sits to the left with her mouth nearly shut and, as is also customary, has her right paw clasped protectively around her cub. The ball and cub are strongly embedded in traditional styling, and explanations for their meaning are offered in the folklore of different East Asian countries. However, their origin and true significance are now obscure.

Similarly, the 'one mouth shut and one open' convention is seen often in guardian figure pairs, and explanations are offered throughout Asia for its significance. Many agree that 'mouth open' signifies vocalisation of the first character, 'a', of the Sanskrit alphabet, and 'mouth shut' the last, 'um', and that together they represent the sound 'om' which expresses the 'Absolute or Ultimate Reality' in the Sanskrit mantra. Another interpretation is that the two sounds represent the 'first and last breath' or the beginning and end of life whilst, in some Japanese traditions, a third suggests in a similar vein that the male lion inhales whilst the lioness exhales, symbolising 'life and death'.

More compelling are the astonishing eyes of the lioness. Whilst her right eye stares fixedly ahead, her left eye is swivelled rearwards as if re-directing her gaze towards, or to some point behind, her mate. This strabismus is clearly intended but its meaning is unclear. Moreover, the skilful modelling of the animal's head and facial contours renders this intriguing and unusual feature almost unnoticeable at first sight to the casual frontal observer.

Remarkable also is the tightly coiled 'coiffure' of the lions' manes which refers strongly to the archaic influence of Greco-Buddhist art from Central Asia in the early days of Buddhism in China in the 5th century.

Azure blue dominates the glaze colour-scheme, covering much of the body area of the lions and a significant proportion of their pedestals. The principal contrast is yellow which is used for the lions' lips, for the palate roof of the open-mouthed male lion, and to outline the musculature of their thighs and shoulders. Yellow also colours manes, their below-chin hair, eyebrows and the inner surface of ears. In places, the yellow colouring is delicately demarcated from the blue glaze alongside by a fine shadow underline in turquoise green, which in places has run on firing and colourfully relieved some otherwise solid blue areas with subtle vertical trails of turquoise. Other colour-detailing includes a bluish-white for the teeth and the sclera of the eyes, whilst dark aubergine is used for fur in shadow, behind the cheek lobes and on the underside of limbs. Aubergine is used also for the body fur of the lionesse's cub and for her mate's brocaded ball which is neatly tied with green and blue ribbons. The lions' eye-pupils are 'dotted' with a very dark, almost black aubergine and a lighter hue is used for the animals' prominent collars which are finely decorated with rosette-shaped studs and bells in a contrasting yellow.

The pedestal supporting the lioness has an old repair which has discoloured, but that of the male lion displays clearly the original colour scheme, which is predominantly blue in background with applied decoration in yellow. The upper face of each pedestal is shaped as a recessed tray that receives the flat register-plate on which the lion is mounted. This measures 60cm x 70cm (24in x 28in) and its low vertical sides are decorated with a band of yellow peonies relieved with green detailing against a blue ground of foliage, a decorative scheme which is mirrored on the lowest band at the base of the pedestal.

The recessed waists of the pedestals bear on each face a square panel fringed with yellow clouds depicting an animal also in yellow, with aubergine detailing in places, against a background of blue clouds and water. Amongst the animals depicted are a hare, a deer, a horse and a mythical qilin in full flight among clouds. Many of these are symbols from Buddhist iconography and similar representations appear also on the banded decoration at the base of the three surviving dragon-screen walls from the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), which are all in Shanxi Province in North China, and date from 1392 to 1607; see C.Eng, Colours and Contrast: Ceramic Traditions in Chinese Architecture, Leiden and Boston, 2015, pp.211-221.

The stepped layers above and below the waisted section are covered successively one with smaller and the other larger stylised lotus petals in yellow, edge-highlighted in green. The petals are applied tightly together so that the blue ground beneath is barely visible. These stylised petals were already prominent as an architectural motif in the early Ming and the smaller versions on the adjacent panels appear more developed stylistically and are probably later in the period.

Whilst yellow and green glazes belong to the sancai 三彩 'three-colour' palette of lead glazes widely used in China from the 5th century onwards, the turquoise, deep blue and aubergine colours belong to the so-called fahua 法华group of glazes (the precise etymology of fahua 法华remains unclear). These are based on complex metal oxide compounds, and were introduced to China from the Middle East during the Yuan dynasty (1271-1368). Fahua colours were later famously deployed together with sancai colours in the polychrome dragon-screen walls of the Ming.

The size, modelling and glaze quality of these lions invites attention. Large glazed ceramic works of this kind belong to a group of objects for which, from the Yuan dynasty onwards, the expertise was developed in craft family workshops in Shanxi Province in North China. These workshops specialised in glazed architectural components, generically referred to in China as liuli 琉璃 which can be translated as 'glaze-work' (for the historical development of Chinese architectural ceramics, see C.Eng, Colours and Contrast: Ceramic Traditions in Chinese Architecture, Leiden and Boston, 2015). Their products ranged from simple roof tiles to large decorative finials composed from separately fired parts and weighing several tons for the roofs of imperial palaces. They also made large figurative statues such as life-sized luohans, 'worthy disciples of Buddha', which were fired in one piece as indeed were these guardian lions, for which similar production methods, discussed below, would almost certainly have been employed (Luohans have recently been the subject of intensive study and the definitive work is by Eileen Hsiang-Ling Hsu, Monks in Glaze: Patronage, Kiln Origin and Iconography of the Yixian Luohans, Leiden and Boston, 2017; see Fig.2 in the printed catalogue for one of the surviving luohan examples discussed below).

Fig.2. Arhat (luohan), Liao dynasty, ca. 1000, Hebei Province, China. Earthenware with three–color (sancai) glaze. @ The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Each lion appears to be moulded in two hollow segments, a head and a body which were subsequently luted (joined with ceramic paste) before firing. In these examples the joint may be concealed beneath their broad aubergine-coloured collars.

Shaping, firing and then glazing shapes as complicated as these would have been a skilful operation. The makers would have wanted not to make these figures as solid objects, because of the risk of explosive failure during firing. Instead, parts were shaped separately as hollow or thin mouldings, assembled by luting using 'slip' (a viscous liquid clay), then air-dried to 'leather-hardness' before initial firing. Parts for the pedestals, being simpler geometric shapes, could be modelled in press-moulds, but parts for the bodies and heads required great skill.

The greatest challenge would have been to hand-mould these parts as thinly as possible to reduce their thermal mass and water content but without the clay slumping during drying or firing. A supporting armature of some kind would have received an initial coarse modelling, followed by the application of a smoother clay to give a 'sculptural' finish to its displayed surface. Completely vegetal material, such as wood or bamboo, would have been unsuitable as an armature-former because it would have carbonised and disintegrated during the first firing at 1000-1100°C. However, X-ray and conservation studies have shown the use in similarly large works of thin metal-rod armatures of wrought iron wound with vegetal fibres which cushioned clay shrinkage during air-drying and, for time enough, the subsequent thermal expansion of the metal rods during firing (see N.Wood, C.Doherty, M.Menshikova, C.Eng and R.Smithies, 'A Luohan from Yixian in the Hermitage Museum: Some Parallels in Material Usage with the Longquanwu and Liuliqu Kilns near Beijing', Bulletin of Chinese Ceramic Art and Archaeology No.6, Beijing, December 2015, pp.34-35).

In these lions particular skill would have been employed in modelling re-entrant areas such as mouths, or the enclosed areas of limbs and lower abdomen, all with adequate support and internal ventilation during air-drying and for escape of steam in firing. In both lions a vent-hole was left behind the mouth at the throat, in the lioness just visible through her clenched teeth, whilst in the body portions can be seen now-plugged vent-holes at the navel and in the small of the back. These were presumably sealed before glazing and subsequent second firing. There may also have been a third vent-hole in the base of the body. The second firing, carried out at a lower temperature of 900-1000°C, would have taken place on a now very dry ceramic body with reduced risk of failure.

Whilst the modelling of the parts would often have been executed from familiar traditional models which evolved only slowly, especially in the case of guardian lions, the glaze-application would have required innovation for every new commission. The shading, interlining, outlining and application of colour fields on pieces such as these would very likely have changed from one commission to the next because such works were often unique demonstrations of the craftsmen's art.

Although the production techniques for these figures was developed in family craft workshops in Shanxi, craftsmen from the province and their linear descendants, together with their jealously guarded techniques, were successively drafted to set up kilns for the construction of the new capital city, first Dadu for the Yuan, and at the subsequently re-named Beijing for the Ming and Qing capitals.

Recent research has established that at least two of the luohan figures, out of ten surviving works now all in museums worldwide, were made from clay whose distinctive compositional markers indicate that it came from a scarce geological deposit in China measuring a compact 8km by 50km. just west of Beijing. In part of this area in the Western Hills, kilns making architectural ceramics still operate under the supervision of contemporary descendants of the original Shanxi craft families (see N.Wood, et al, 'A Luohan from Yixian in the Hermitage Museum', Beijing, 2015, pp.31-33).

The unusual predominant colour of the lions may connect in another way with both Buddhism and Shanxi Province. The mountainous Wutaishan region, in the north-east of Shanxi lies roughly 300km west of Beijing, and has some seventy important surviving ancient Buddhist temple-sites. Most were founded in the Ming but some earlier and two survive from the Tang dynasty (618-907). Beginning in the 5th century, repeated accounts of local apparitions and mystical phenomena led Wutaishan to become a major destination for Lamaist (Tibetan Buddhist) pilgrims from Mongolia, China and the Himalayan Plateau including Tibet and Northern India. In time, the region became identified with the earthly home of Mañjuśrī (in Chinese Wenshu 文殊), the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, in honour of whom many temples and temple halls were richly endowed (a Bodhisattva is a person who has delayed making the final step to nirvana and Buddhahood in order further to conduct good worldly deeds). Patrons included from earliest times members of the (Buddhist) imperial families whose rulers were considered to be imbued with the qualities of Wenshu, their patron deity.

Wenshu is sometimes associated emblematically with a blue lotus and is often represented riding a blue lion, the combined representation said to signify iconographically the achievement of mental composure through wisdom. Such a figure of Wenshu astride a blue lion stands in the Shuxiangsi 殊像寺 (The Temple of the Likeness of Wenshu) in Wutaishan. It is an imposing 10 meters in height overall, though made not of ceramic but of plaster and other materials. It is possible that the colour of the guardian lions under discussion might be a metaphoric reference to Wenshu and possibly therefore to the temple for which they were commissioned.

In conclusion, these lions were probably made by leading craftsmen from Shanxi Province working either in Shanxi or near to Beijing, and they were very possibly commissioned for an important and generously endowed temple dedicated to the Bodhisattva Mañjuśrī (Wenshu). The glazes used were all fully developed by the mid to later Ming and the lotus petal motifs and animal figures on the pedestals are consistent with that period. These lions are an exceptional example of the liuli master's art exhibiting timeless quality and their own exotic ancestry.

The Newark Museum, New Jersey; © 2018. The Newark Museum/Art Resource/Scala, Florence.

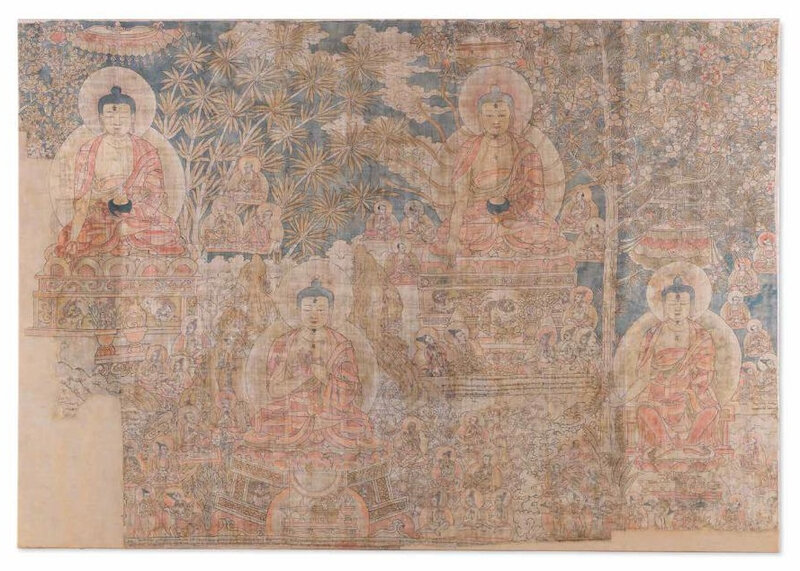

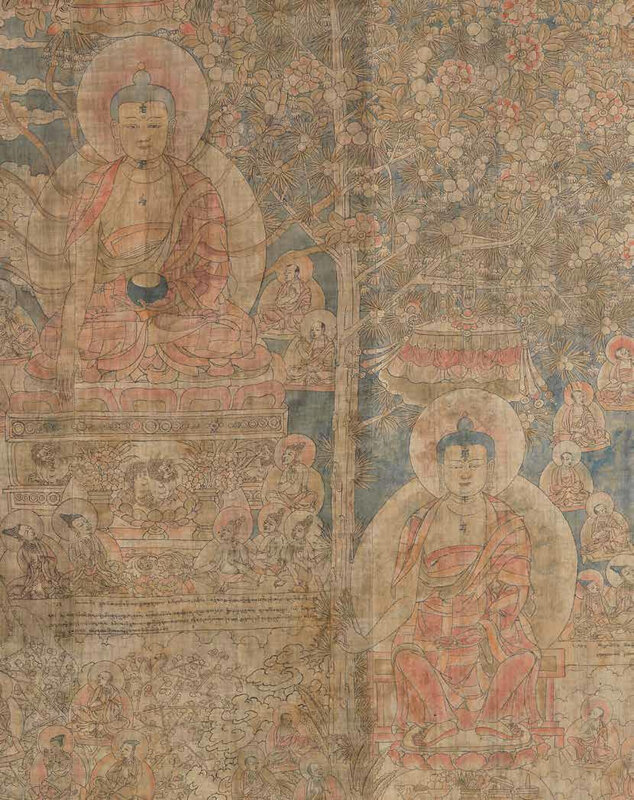

A large selection of Buddhist art includes a rare and large painting of the Cosmic Buddhas, East Tibet, 14th/early 15th century, which is estimated at £130,000 - 150,000 (Lot 107). This painting is a rare early surviving example depicting four of the Five Cosmic Buddhas. Unusually, the painting fuses elements of Tibetan pictorial traditions with Chinese stylistic conventions.

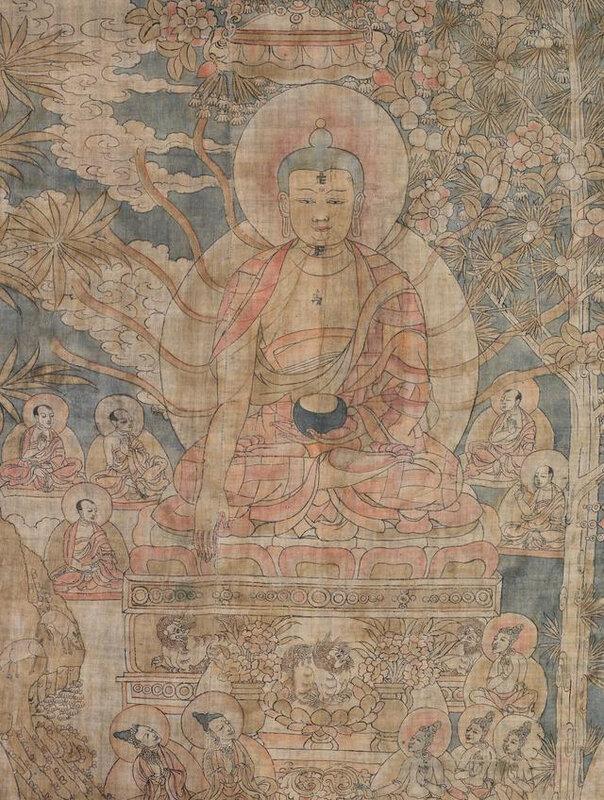

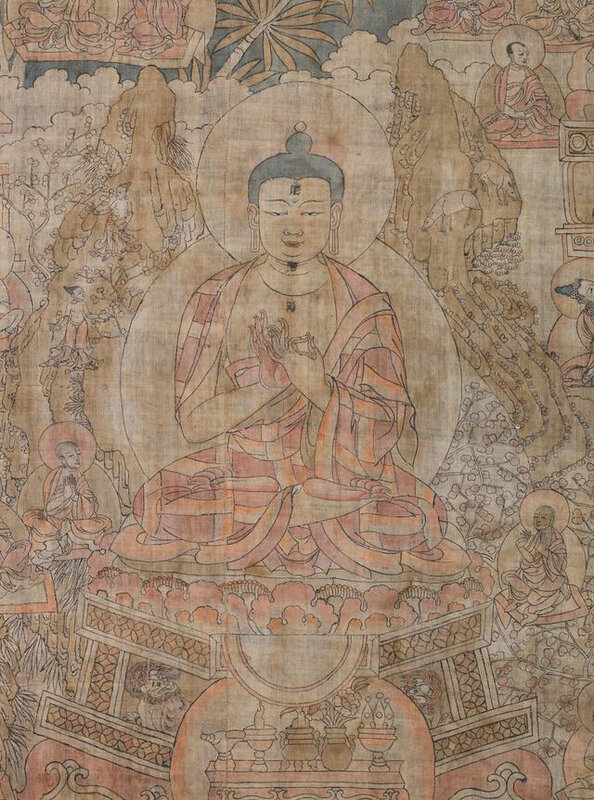

Lot 107. A rare and large painting of the Cosmic Buddhas, East Tibet, 14th-early 15th century. Distemper on cloth, 241cm x 172cm (95in x 67 6/8in). Estimate £ 130,000 - 150,000 (€ 150,000 - 170,000). Unsold. © Bonhams 2001-2018

Provenance: a European private collection.

The result of Adamantio s.r.l. Science in Conservation Laboratory, Turin, TSC-HD carbon 14 test, 2007, notes 95.4% probability of the date between 1300-1420 AD.

Note: Monumental in size, this exceptional painting is an early surviving Tibetan example depicting four of the Five Cosmic Buddhas who, from at least the first century AD, were thought to coexist at the same time in various parts of the universe. These Buddhas were considered emanations of the Historic Buddha Shakyamuni, and each was associated with a specific colour, position, gesture etc.

Seated on a lion throne in the foreground is Vairocana, recognisable by his hand gesture of setting in motion the Wheel of the Doctrine, symbolic of the Tathagata family to which he belongs. He occupies the central position in the universe and is associated with pure and absolute wisdom defeating the evil of ignorance. The Buddha Amitabha would have sat on Vairocana's right, while to his left sits Amoghasiddhi, presiding over the northern quarter of the universe and displaying the gesture of absence of fear and reassurance towards the devotees surrounding him. He belongs to the Karma family and is associated with active wisdom defeating the evil of envy. The third figure, Akshobhya, sits in the background between Vairocana and Amoghasiddhi, holding his right hand in bhumisparsa mudra. He presides over the blissful land of the East, Abhirati, representing consciousness as an aspect of reality. To the upper left is Ratnasambhava, belonging to the Jewel family and presiding over the southern quarter of the universe. He is shown with the gesture of giving spiritual riches to the devotees surrounding him and is associated with wisdom opposing evil born of feelings.

The inscriptions on the painting relate to four of the fifteen miraculous deeds performed by Shakyamuni at Shravasti. These days correspond to the first fifteen in the first month of the Buddhist calendar adopted in Tibet. This painting was thus likely to have been commissioned on the occasion of the New Year celebrations taking place in Tibet. The fusion of Tibetan pictorial traditions and Chinese stylistic conventions, noted in the vaporous clouds, bamboo and flowering prunus branches surrounding the deities, probably derived from the several visits paid by the high-ranking members of the Tibetan clergy to the Court of the Yuan dynasty emperors. Two large Buddhist paintings dating to the Yuan dynasty, including a large fresco depicting the Maitreya heavens, dated to 1298, from the Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto (acc.no.933.6.1), and a painting of the Buddha of Medicine, 1320, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (acc.no.65.29.2), show a similar treatment of clouds and physical traits of the Buddhas that can be seen in the present work. An earlier depiction of the Shakyamuni Buddha, dated between 1181 and 1186 and from the National Palace Museum, Taipei (acc no.n2006110384), depicts a similar foliage surrounding the holy figures.

The first inscription on the lowest margin, to Amoghasiddhi's right, refers to the first day in spring, when Shakyamuni travelled to a field that had been prepared for his visit and sat upon a 'lion' throne. After receiving offerings from his lay follower Prasenajit, the ruler of Kosala, the Buddha planted a toothpick on the ground, which immediately grew into a tree bearing beautiful leaves, flowers, fruit and jewels. When the tree rustled in the wind the sounds of the Buddha's teachings were heard. Embodying the Buddha Shakyamuni, Amoghasiddhi's parasol is depicted hanging from a branch of the miraculous tree mentioned in the inscription.

The inscription on the left, on the lowest margin of the painting, refers to the second day, when king Udrayana presented great offerings to Shakyamuni, who turned his head to the right and to the left, making two mountains emerge on each side, one covered with grass to feed animals, the other with food to satisfy humans. Then the Buddha taught the dharmaaccording to each individual's ability and more came closer to enlightenment by listening. The two mountains are depicted on the present work flanking Vairocana.

The inscription below Akshobya's throne relates to the miracle performed by Shakyamuni on the fifth day, when king Brahmadatta of Varanasi prepared various offerings for him. A golden light shone from the Buddha's face and filled the entire world, reaching all living beings and purifying the three poisons: desire, hatred and ignorance. The golden light emanating from Shakyamuni is depicted here as rays emanating from the radiant face of Akshobya.

The remnants of the inscription on Amoghasiddhi's left, refer to the miracle performed by Shakyamuni on the sixth day, when the Licchavi people made offerings to him. The Buddha allowed those present to examine each other's mind so everyone could understand others' good and evil thoughts. All of them experienced great faith and, after Shakyamuni taught the dharma, thus many attained great understanding and enlightenment and many secured a future rebirth as humans or gods.

Bonhams would like to thank Ernesto Lo Bue and Adriano Fabbroni for translating the inscriptions and Dr. Giuseppe Baroetto for his suggestions concerning their interpretation.

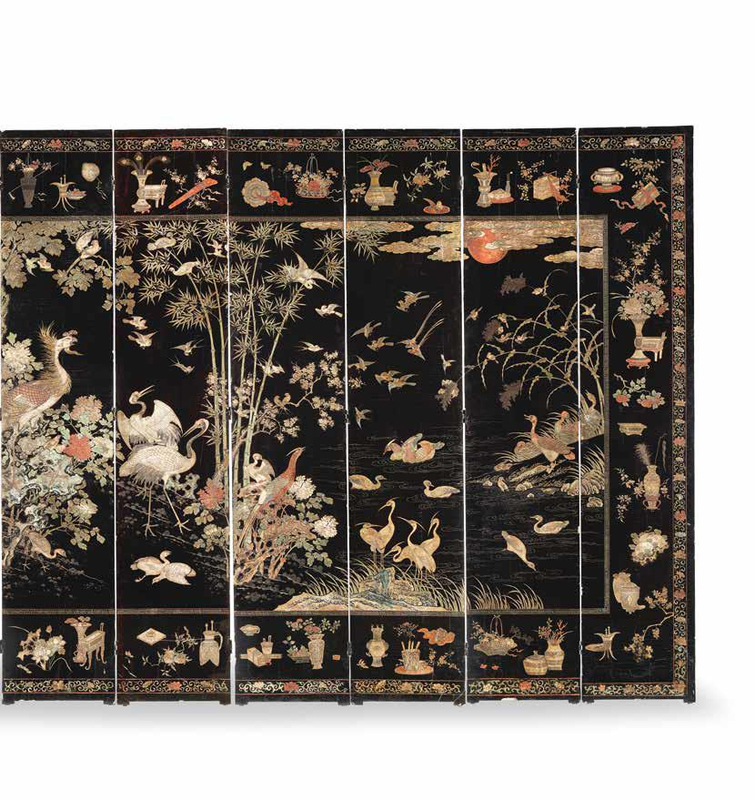

A select number of imposing lacquer screens will be offered, including a rare coromandel ten-leaf lacquer 'Palace' screen, cyclically dated to the Dingmao year, corresponding to 1687 and of the period, estimated at £70,000-100,000 (Lot 71); and a magnificent and rare twelve-leaf double-sided coromandel lacquer screen, Kangxi period, from a Royal Collection, which is estimated at £60,000-80,000 (Lot 75). Such screens were expensive and laborious to produce, and were aimed at high-ranking officials, scholars and gentry who commissioned them to commemorate important events. Also offered in the sale are a number of Imperial textiles including a rare Imperial yellow-ground embroidered 'nine dragon' kang cushion cover, Qianlong, estimated at £30,000-50,000 (Lot 74).

Lot 71. A rare Coromandel ten-leaf lacquer 'Palace' screen; Cyclically dated to Dingmao year, corresponding to 1687 and of the period; 208.1cm (81 7/8in) high x 502cm (197 1/2in) wide. Estimate £ 70,000 - 100,000 (€ 80,000 - 110,000). Unsold. © Bonhams 2001-2018

Exquisitely decorated on one side with a detailed palace scene showing a delegation approaching from the far right, a flag with the character shuai flies above and stands next to the gate, in the centre of the enclosed palace is a dignitary, entertained by dancers, the rear of the palace with courtly ladies and ponds, the border decorated with chi-dragons, the reverse with a long dedicatory inscription by the scholar Gong Zhang in fine xingshu calligraphy in gold, further to the left the names of donors. (10).

Provenance: Marquis de Trazegnies

Gisele Croes Arts D'Extreme Orient, Brussels

A Belgian private collection, acquired from the above on 21 June 1990.

Note: The present lot was destined for the domestic market and not for export, as is clearly demonstrated by the lengthy inscription.

Such screens were highly expensive and laborious to produce, and were aimed at high-ranking officials, scholars and gentry who commissioned them to commemorate important events. The present lot appears to have been commissioned by a group of officials who are named on the far left, for the birthday of General Meng Wengjin 夢翁金. The long dedicatory essay was written by Gong Zhang 龔章 (1637–1695).

The palatial scene on the screen depicts a reception or banquet given by General Guo Ziyi 郭子儀 (697-781), a celebrated figure who was credited with saving the Tang dynasty by putting down the An Shi rebellion. He was later made a prince and eventually deified in popular culture as a God of Wealth and Happiness. The subject would have made this screen a highly appropriate birthday gift for a military general such as Meng Wengjin.

The lengthy encomium on the reverse was written by the official and educator Gong Zhang. Originally from Guishan County (now Huizhou), at age 24 he was of the highest-grade exam candidates. In 1673, Gong achieved the highest degree of jinshi and became in charge of the Hanlin examiners. He later hosted the exams in the Jiangnan region and passed many famous scholars.

Several coromandel lacquer screens with similar scenes of palaces and processions, Kangxi, are illustrated by W.De Kesel and G.Dhont in Coromandel: Lacquer Screens, Gent, 2002, pp.40-44. See also further examples illustrated by M.Beurdeley, Le Mobilier Chinois: Le Guide du Connaiseur, Fribourg, pp.135-142.

Lot 75. A magnificent and rare twelve-leaf double-sided 'coromandel' lacquer screen, Kangxi (1662-1722); overall 636cm (250 1/3in) wide x 203.8cm (80 2/8in) high. Estimate £ 60,000 - 80,000 (€ 68,000 - 91,000). Sold for £ 344,750 (€ 394,676) inc. premium. © Bonhams 2001-2018

Exquisitely decorated on the front with a detailed scene of court ladies within a palatial landscape, all enclosed within a border carved with the 'Hundred Antiques', the reverse depicting 'one hundred birds courting the phoenix', with a central pair of phoenix perched on rockwork beside flowering peony, with numerous other birds including egrets, crane, pheasants and mandarin ducks. (12).

Provenance: a Royal Collection.

Lot 74. A rare imperial yellow-ground embroidered 'nine dragon' kang cushion cover, Qianlong (1736-1795); Estimate £ 30,000 - 50,000 (€ 34,000 - 57,000). Sold for £ 125,000 (€ 143,102) inc. premium. © Bonhams 2001-2018

Of rectangular form, delicately worked in shades of red, blue, green, and white satin stitch and couched gold threads with a full-frontal five-clawed dragon coiled around a flaming pearl, flanked by eight ferocious dragons in different poses, all leaping amidst leafy lotus scrolls and trailing clouds, all within a border of turbulent waves and terrestrial diagrams surrounded by a key-fret band, the outer border with alternating designs of phoenixes and bats on further floral scrolls, framed and glazed.

Provenance: Spink & Son, Ltd., London, 16 January 1953 (invoice), according to which it was "Taken from a table in the private apartments of the Empress T'zu-Hsi, during the Boxer Rebellion, 1900."

An English private collection.

Note: Delicately woven with nine five-clawed dragons pursuing flaming pearls, this brilliant cover evokes multiple layers of auspicious meanings relating to the figure of the empress and her quest of attaining immortality. Capable of flying high in the sky and diving back in the sea, dragons were, since the earliest phases of Chinese history, seen as intermediaries between Heaven and Earth and regarded as vehicles transporting humans to immortal realms. According to the 'Book of Songs', compiled in the third century BC, dragons represent victory over the forces of darkness, cast light onto the Gate of Heaven and allow one to glimpse the wondrous residence of immortal beings. Complementing the design, the phoenix, symbolic of the empress, inhabited the immortal lands of the Queen Mother of the West, source of eternal light and the profusion of lotus, symbolic of Buddhist enlightenment, recalls the floral showers that accompanied the birth of the Buddha.

The refinement of the embroidery characterising the present cover suggests that it may have been produced during the reign of the Qianlong emperor, when the silk industry reached the highest standards of its aesthetic development. Compare with a yellow-ground silk cover embroidered with designs of nine dragons, 18th century, in the Victoria and Albert Museum, illustrated by V.Wilson, Chinese Textiles, London, 2005, pl.39. A yellow-ground cover for a stool, decorated with similar designs of dragons, phoenix and bats and dated to the second or third quarter of the eighteenth in the Art Institute of Chicago, is illustrated by J.Vollmer, Clothed to Rule the Universe, Chicago, 2000, p.26, pl.VII.

A much smaller yellow-ground silk 'dragon' throne seat cover, 18th century, was sold at Sotheby's New York, 17 September 2013, lot 238.

A selection of paintings by the artist Lin Fengmian (1900-1991), from distinguished European private collections, will also be offered with estimates ranging from £5,000-30,000 (Lots 307-315).

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F62%2F90%2F119589%2F129832900_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F61%2F119589%2F129832828_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F01%2F04%2F119589%2F129831900_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F09%2F18%2F119589%2F129831747_o.jpg)