Gold Earrings of Last Queen of The Punjab Achieve Eight Times Their Estimate at Bonhams

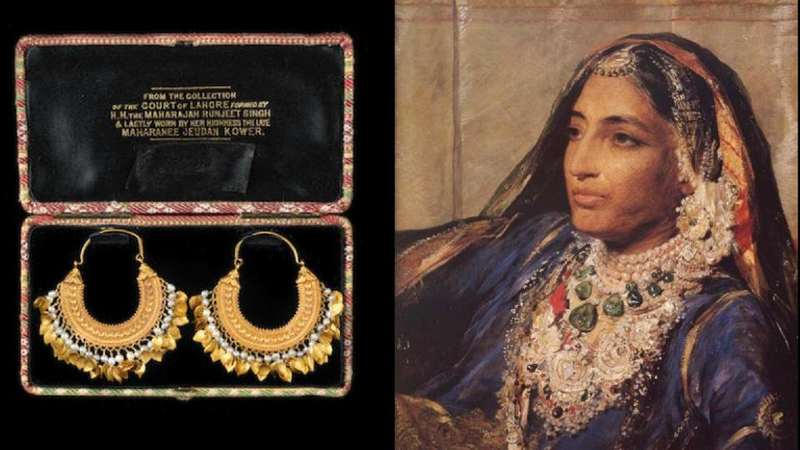

The earrings were part of a collection plundered by the British army when she was deposed in 1846. The items then confiscated and brought to London included the Kohinoor diamond and the Timur Ruby.(Photo courtesy: Bonhams and Wikipedia)

LONDON - A pair of gold pendant earrings from the collection of Maharani Jind Kaur, the mother of the last Sikh ruler of the Punjab, sold at Bonhams Islamic and Indian sale in London today (24 April) for an impressive £175,000. The earrings had been estimated at £20,000-30,000.

Bonhams Head of Islamic and Indian art, Oliver White, said, "These gold earrings are a powerful reminder of a courageous woman who endured the loss of her kingdom, and persecution and privation, with great dignity and fortitude. The impressive price paid for these beautiful pieces of jewellery conveys their significance."

Lot 300. A pair of gold pendent earrings from the collection of Maharani Jindan Kaur (1817-63), wife of Maharajah Ranjit Singh, the Lion of the Punjab (1780–1839), Punjab, probably Lahore, first half of the 19th Century. Sold for £ 175,000 (€ 199,543) © Bonhams 2001-2018

each crescentic and on gold loops, finely decorated with granulation, the terminals with floral motif, the lower edge with a band of suspension loops, each with a seed pearl and small gold leaf pendant, verso undecorated; in a fitted box covered in an Indian cotton with inscription stating: 'From the Collection of the Court of Lahore formed by H.H the Maharajah Runjeet Singh & lastly worn by Her Highness the late Maharanee Jeudan Kower'; 6.5 cm. high; the case 8 x 14.5 cm., 46. g. (total weight)(3)

Provenance: Collection of Maharani Jindan Kaur (1817-63), wife of Maharajah Ranjit Singh (1780-1839).

Sold by Frazer and Hawes from Garrards of Regent Street, London.

Formerly in a European private collection (early 1930s-present).

Note: Two necklaces from the Maharani in similar fitted cases have been sold at auction: Bonhams, Islamic and Indian Art, 8th October 2009, lot 366; and Christie's, Magnificent Mughal Jewels, London, 6th October 1999, lot 178.

An important emerald and seed-pearl Necklace from the Lahore Treasury, worn by Maharani Jindan Kaur (1817-63), wife of Ranjit Singh, the Lion of the Punjab (1780–1839) Lahore, first half of the 19th Century. Sold for £ 55,200 (€ 62,941) at Bonhams, Islamic and Indian Art, 8th October 2009, lot 366. © 2002-2009 Bonhams 1793 Ltd

Cf. my post: 19th Century Necklace Owned by Wife of Last Sikh Ruler for Sale @ Bonhams

Between 1849 and 1850, when the British took control of the court in Lahore, they entered the Treasury, where they found the court jewels wrapped in cloth. The Treasury was fabled to be the greatest and largest treasure ever found. The most famous and well-known jewels were taken away as gifts for Queen Victoria, including the Koh-i Noor and the Timur Ruby. Confiscated treasures were sold by Messrs Lattie Bros. of Hay-on-Wye in the Diwan-i-Am of the Lahore Fort. The items were listed in seven printed catalogues and the sales took place over five successive days, the last one starting on 2nd December 1850. It is also known that some of the jewels were boxed in Bombay by Frazer and Hawes and were sent to London, where they were sold by Garrards. Based on the case, this would have been done after the Maharani's death.

Maharani Jindan Kaur

Maharani Jindan Kaur was born in 1817 in Chahar, Sialkhot, Punjab. Of humble origins, she was the daughter of Manna Singh Aulak, the Royal Kennel Keeper at the Court of Lahore. She grew into a young lady of exquisite beauty and came to the attention of Maharajah Ranjit Singh at a young age. Manna Singh was reported to have pestered the Maharajah, promising that his daughter would make him youthful again. In 1835, she became Ranjit Singh's seventeenth wife and in 1838 bore him a son, Duleep. Duleep was his last child and just ten months later Ranjit Singh died following a stroke. Jindan was the Maharajah's only surviving widow, rejecting the practice of 'Sati' or throwing herself on the funeral pyre with his other wives, choosing to bring up her young son instead.

Ranjit Singh's empire stretched from the Indian Ocean to the Himalayas, with its southern boundary bordering British India. His court was fabled for its patronage of the arts and sciences, and for its riches. The Russian painter Alexis Solykoff wrote on visiting the court: "What a sight! I could barely believe my eyes. Everything glittered with precious stones and the brightest colours arranged in harmonious combinations". Upon the Maharajah's death, his body was carried through the streets to his funeral pyre in a golden ship, "with sails of gilt cloth to waft him into paradise'. Immediately after his death, Ranjit Singh's golden empire began to crumble. His eldest son, Kharak Singh took the throne, but was murdered two years later; the reign of Sher Singh was similarly short-lived and he was assassinated in 1843, upon which the five year old Duleep was proclaimed Maharajah, with his maternal uncle as Prime Minister and his mother, Jindan, as Regent. His uncle's position as Prime Minister was brief, after the Khalsa Army declared him a traitor and killed him. As Jindan came to power, she was swiftly confronted by the British army that had moved to her southern border in the hope of conquering one of the last independent states of Northern India.

As Regent, Jindan became a thorn in the side of the East India Company. She waged two unsuccessful wars against the British, the First and Second Anglo-Sikh Wars of 1846-49, which brought about the annexation of the Punjab. In 1846 she was deposed as Regent and in February 1847 the British took possession of the capital, Lahore, installing Sir Henry Lawrence as British Resident to oversee their affairs. The British continued to see her as a major threat to their control of the Punjab, since she was instrumental in organising Sikh resistance, rallying her armies to battle and plotting rebellion against the British. Thus in August 1847, to halt her influence on the young king, Duleep was sent away from the palace, Jindan was ordered by Sir Henry Lawrence to the Summan Tower of Lahore Fort, and was then incarcerated in the fort at Sheikhurpura. After being moved around several prisons, in 1849 she escaped from British captivity at Chunar Fort, leaving a note for the British: "You put me in a cage and locked me up. For all your locks and your sentries, I got out by magic....I had told you plainly not to push me too hard – but don't think I ran away, understand well that I escape by myself unaided...When I quit the fort of Chunar I threw down two papers on my gaddi and one I threw on a European charpoy, now don't imagine I got out like a thief!". Disguised as a beggar woman, she fled to the Himalayas, where she found troubled sanctuary in Kathmandu, Nepal. All her jewels and gold that had been left in the government treasure in Benares were confiscated, with the added threat that if she went to Nepal she would lose her pension as well.

In Kathmandu, she lived under the protection of the Nepalese King and government, and spent her time studying scriptures and doing charitable work through a temple she had built near her house. Life was not easy for her and she was kept as a virtual prisoner with a meagre allowance. Under pressure from the British officials at Kathmandu, who portrayed her as dangerous with her alleged efforts to create disaffection against the British, the Nepalese imposed humiliating restrictions upon her. In the meanwhile, the British press began a campaign to blacken her name, calling her the 'Messalina of the Punjab', a term first coined by Governor-General Lord Hardinge. Like Messalina, the wife of the Roman Emperor Claudius, Jindan was portrayed as a licentious seductress, who was powerful and influential, and too rebellious to control.

The young Maharajah, Duleep, was moved to Fategarh, where he lived under the guardianship of Dr John Login and his wife, and eventually arrived in Britain in 1854, at the age of sixteen, where he was adopted as a godson by Queen Victoria. Under the influence of the Logins, he converted to Christianity and was brought up as a young English gentleman. In 1860, Duleep sent his native attendant to Kathmandu to find out about his mother and a report came back through the British resident at Nepal that: "The Rani had much changed, was blind and lost much of her energy, which formerly characterised her, taking little interest in what was going on". The Governor General agreed to a meeting based on this report of the Rani's condition, thinking that the last queen of the Punjab no longer posed a threat.

In 1860, tired of her exile and isolation, and the indignity she was made to suffer, she travelled to meet her son in Calcutta. For the first time in thirteen and a half years, they were reunited at Spence's Hotel in January 1861. Duleep found her almost blind and suffering from poor health. He offered her a house in Calcutta, but she expressed her wish to stay with her son, following years of enforced separation. And so it was agreed that the Rani would travel to England. Her private property and jewels, previously taken by the British authorities, would be restored to her on the basis that she left India and in addition she would be granted a pension of £3,000 per annum. Her jewels were returned to her at Calcutta at the start of the journey.

The Maharajah returned to London with his mother and took a house in Bayswater. Lady Login observed: "The half-blinded woman, sitting huddled on a heap of cushions on the floor with health broken and eyesight dimmed, her beauty vanished, it was hard to believe in her former charms of person and conversation! However, the moment she grew interested and excited in a conversation unexpected gleams and glimpses of the torpor of advancing age revealed the shrewd and plotting brain of the one who had been known as the 'Messalina of the Punjab'".

Lady Login noted a change in the Maharajah and for the first time heard him talk about his private property in the Punjab, information that only Jindan could have given to him. It is possible that the Rani saw it as a chance for retribution against the British for what they had done. During this time, she reawakened her son's true faith and royal heritage, telling him stories of all that had been lost to the British. She had sown the seeds of discontent in Duleep Singh's mind, which would bring about his fall from grace in later life. John Login tried to persuade the Maharajah to find his mother a separate house, feeling that her influence was bad for him. This did not happen until 1862 when she was moved to Abingdon House in Kensington under the charge of an English lady.

By 1863, Duleep Singh had set his sights on the Elveden Estate in Suffolk. On the 1st August of the same year, Jindan died in her Kensington home in the country of her sworn enemy, just two and a half years after being reunited with her son and leaving him inconsolable.

As a Sikh queen, cremation was the traditional practice, but one that was not allowed under English law. With the help of John Login, the Maharani's body was moved to the Dissenters Chapel at Kensal Green Cemetery until such time that it could be take to India for the last rites. The simple ceremony at Kensal Green was attended by a number of Indian dignitaries and the Maharani's retinue that she had brought with her, and the Maharajah spoke to them in their own language. Her body remained at Kensal Green for nearly a year and recently a marble gravestone bearing her name inscribed in English and Gumurkhi was found in the catacombs of the Dissenters Chapel. At the time, Charles Dickens wrote: "Down here in a coffin covered with white velvet, and studded with brass and nails, rests the Indian dancing woman whose strong will and bitter enmity towards England caused Lord Dalhousie to say of her, when in exile, that she was the only person our Government near feared".

In 1864, permission was granted to take the body to India, which had been her dying wish, and she was cremated at Bombay (Duleep was not allowed to go to the Punjab), her ashes scattered on the Godavai and a small memorial or samadh erected on the left bank. In 1924, her ashes were later moved to Lahore by her grand-daughter Princess Bamba Sutherland, and deposited at the samadh of Ranjit Singh. Finally the 'Messalina of the Punjab' returned home to rest. In 2006, whilst clearing the catacombs at Kensal Green Cemetery, the Rani's marble headstone was found broken. It was restored and unveiled at Thetford's Ancient House Museum in 2008.

Bibliography: Peter Bance, The Duleep Singhs. The Photograph Album of Queen Victoria's Maharajah, Stroud, 2004

Peter Bance, Sovereign, Squire and Rebel. Maharajah Duleep Singh, London, 2009

Christy Campbell, The Maharajah's Box, London, 2000

Patwant Singh and Jyoti M. Rai, Empire of the Sikhs. The Life and Times of Maharaja Ranjit Singh, London, 2008

Other highlights of the sale include:

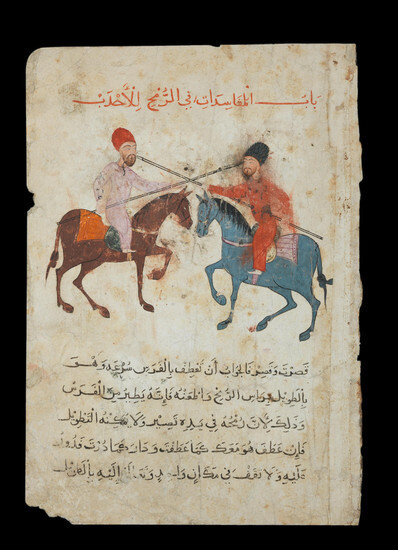

• An illustrated leaf from a Mamluk manuscript on horsemanship, depicting two lancers engaged in a combat exercise Egypt or Syria, late 14th/ early 15th Century sold for £47,500. It had been estimated at £3,000-£4,000.

Lot 7. An illustrated leaf from a Mamluk manuscript on horsemanship, depicting two lancers engaged in a combat exercise, Egypt or Syria, late 14th/early 15th Century. Estimate £3,000-£4,000. Sold for £ 47,500 (€ 54,161). © Bonhams 2001-2018

Arabic manuscript on paper, 15 lines to the page written in naskhi script in black ink, heading and significant words picked out in red, staining, slight losses to edges, 237 x 166 mm.

Provenance: Private Swiss collection.

Note: This leaf appears to derive either from an incomplete manuscript in the Keir Collection, referred to as 'The Furusiyya Manuscript', or from another, closely related to it. See B. W. Robinson, E. J. Grube, G. M. Meredith-Owens, R. W. Skelton, Islamic Painting and the Arts of the Book, London 1976, pp. 72-81 (where two illustrations of lancers are listed), and especially Plate 12 (no. II.8), where the leaf shown bears a strong resemblance to the present leaf, both in terms of the illustration and the hand in which the text is written.

Comparison can be made with another illustrated folio depicting two mounted lancers in an Arabic manuscript on the sciences by Muhammad bin Ya'qub ibn Khazzam al-Khuttali, entitled Kitab al-makhzun fi djami' al-funun, copied in AD 1474: see De Baghdad a Ispahan, exhibition catalogue, Milan 1994, pp. 170-177, no. 34. See also S. Carboni, 'The Arabic Manuscripts', in Pages of Perfection: Islamic Paintings and Calligraphy from the Russian Academy of Sciences, St. Petersburg, Milan 1995, pp. 84–89; J–P Digard, Chevaux et Cavaliers Arabes dans les Arts d'Orient et d'Occident, Paris 2002, pp. 103–107.

• Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh (Indian, born 1937) Composition in green and black inscribed on the reverse with the artist's name sold for £40,000.

Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh (India, born 1937), Composition in green and black, inscribed on the reverse with the artist's name, oil on canvas, 131.5 x 121.5cm (51 3/4 x 47 13/16in). Sold for £ 40,000 (€ 45,610). © Bonhams 2001-2018

Provenance: Private UK collection: a gift to the vendor from the artist.

Note: Ghulam Mohammed Sheikh was born in Surendranagar, Gujarat in 1937 and is acknowledged as one of the most influential artistic figures of his generation. A central figure of the Baroda school, he is also an art historian, Professor of painting and eminent Gujarati poet. His presence at the core of the Baroda school was deeply significant.

Whilst a student in London, he regularly visited the collection of Indian miniatures at the V&A: his work has often displayed the busy landscapes and multiple narratives found in miniature paintings. The present work is a departure from much of Sheikh's early pieces in terms of its simple composition with few figurative elements, however it continues to explore the use of pictorial space seen in some of his busier compositions. The few figurative elements which are depicted are placed disparately on the canvas but drawn together with line and colour: their relation to one another is left open to interpretation by the viewer. Much like a great deal of Sheikh's early work, it is imbued with a sense of the surreal and the fantastical; it explores the use of bright, almost psychedelic colours which is typical of his style in the 60s and 70s. The calm, thoughtful figure to the centre contrasts with the vivid colour and abstract linear motifs on the left of the canvas to highlight Sheikh's concern with bringing together the physical and the transcendental.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F76%2F25%2F119589%2F129014052_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_ac5c4c_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_709b64_304-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_22f67e_303-1.jpg)