A magnificent blue and white moonflask, Qianlong six-character seal mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1736-1795)

Lot 2751. A magnificent blue and white moonflask, Qianlong six-character seal mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1736-1795); 23 ¼ in. (59 cm.) high. Estimate HKD 60,000,000 - HKD 80,000,000. Price realised HKD 69,850,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2018

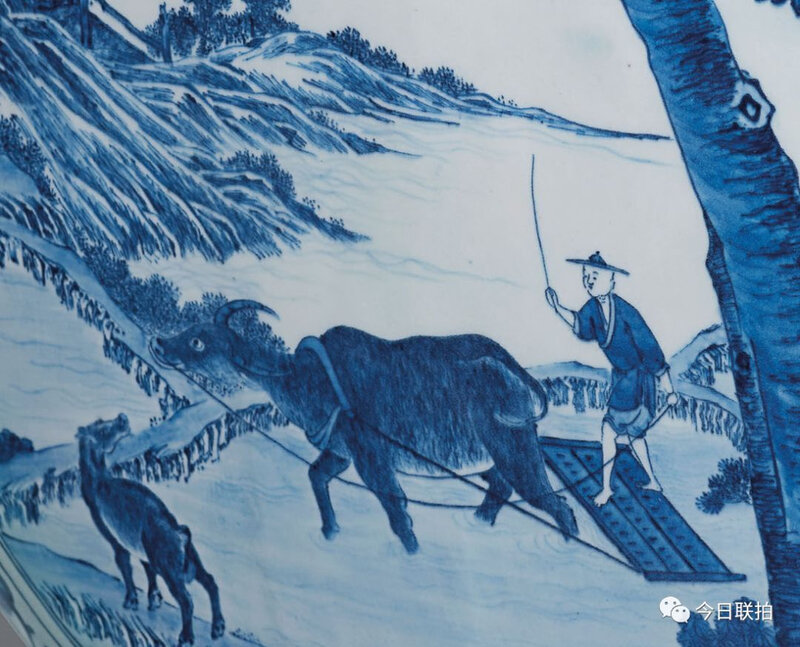

The circular body of oval section is raised on a splayed base and surmounted by a waisted neck flanked by bat-form handles holding lingzhi in their mouths, each side is finely painted in varying shades of bright cobalt blue with a farmer cultivating a field with a buffalo below paulownia trees, the short sides painted with scrolling peonies, and stylised shou characters suspending musical chimes, the base and the rim with a band of ruyi heads, box.

Provenance: Edward T. Chow Collection, sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 3-4 May 1994, lot 172

An Asian private collection

Dragon & Phoenix – 800 Years of Patronage, sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 1 November 2004, lot 902.

Exhibited: Galleries of the Baur Collection, Geneva, One Man's Taste, Treasures from the Lakeside Pavilion, 1988-1989, Catalogue, no. C15

Bountiful Harvest – A Magnificent Qianlong MoonFlask

Rosemary Scott, Senior International Academic Consultant Asian Art, Asian Art

This large, rare and magnificent flask is skilfully painted in rich underglaze cobalt blue with a large circular panel containing an agricultural scene on each side surrounded by a formal peony scroll. On either side of the neck are bat-shaped handles each one holding a lingzhi fungus of immortality in its mouth. Painted front and back of the neck are two more bats. All the bats – both painted and as handles - are depicted upside-down. Since bats are a symbol of happiness and the word for upside-down is a rebus for ‘arrive’, these bats symbolise the arrival of happiness. On either side of the flask, below the handle, is painted a lotus flower from which is suspended a complex hanging which appears to combine the Swastika symbol 卍 representing wan (ten thousand) and the character shou (longevity) – suggesting ten thousand years of long life. Below that is a suspended qing chiming stone, which is a rebus for qing celebration and jiqing auspicious happiness. The major decorative panel on either side of this moonflask does not merely represent an attractive bucolic scene of a peasant tilling his fields, which might appeal to a Chinese literatus dreaming fondly of a simple life away from the exigencies of official duties. It has much more important symbolism.

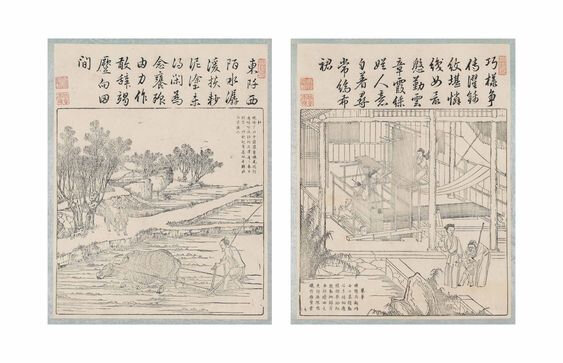

The immediate inspiration for the scenes on either side the flask is the famous 1696 imperial publicationYuzhi Gengzhi tu, sometimes known as the Peiwen zhai Gengzhi tu. In English this is usually known as‘Pictures of Tilling and Weaving’ or ‘Pictures of Agriculture and Sericulture’ and contained 23 illustrations of agriculture and 23 illustrations of sericulture, each accompanied by the Kangxi Emperor’s seven-character quatrains. A copy of this 1696 publication was sold by Christie’s London on 14 May 2013, lot 97 (fig. 1)in the sale of The Hanshan Tang Reserve Collection. The original version of the Gengzhi tu was written by the Southern Song scholar Lou Shou (1090-1163), whose courtesy name was Lou Shouyu or Lou Guoqi. He came from Yinxian in the prefecture of Mingzhou (modern Ningbo) and took up the post of magistrate ( ling) of Qianxian. He had considerable respect for the peasants and compiled a book illustrating details of their activities. The two juan book was eventually completed in 1132 and was submitted to Emperor Gaozong (r. 1127-1162), who welcomed it as another way to promote productive agriculture. The transmitted version of the Song dynasty Gengzhi tu consists of 21 images of agriculture and 24 pictures of sericulture accompanied by 45 five-syllable descriptive poems. This book not only described the technical processes involved with agriculture and sericulture, but also provided details of many of the implements involved. The first printed edition was eventually published around 1237 by Lou Shou’s grandsons Lou Hong and Lou Shen. Further publications of the Gengzhi tu by other authors, such as Liu Songnian in the Southern Song period and various authors in the Yuan and Ming dynasties largely copied Lou Shou’s original work.

fig.1. Jiao, B. Yuzhi Gengzhi Tu -- Imperially Commissioned Illustrations of Tilling and Weaving. Beijing: 1696. 2° (383 x 291mm). Woodblock printed calligraphic preface and 46 full page woodblock illustrations mounted in an accordion-style album. Text in Chinese. Original brocade-covered boards (extremities rubbed). Sold for 37,500 GBP at Christie’s London, 14 May 2013, lot 97. © Christie's Images Ltd 2013

In the Qing dynasty the Kangxi Emperor ordered the court painter Jiao Bingzhen (active c. 1680-1720) to revise the Gengzhi tu and to produce a fine dianben (palace edition) which could be distributed throughout the empire. Jiao, whose work shows the influence of the European Jesuit missionaries at the Chinese court, created exceptional images, which feature aspects of linear perspective. The finest woodblock cutter of the day, Zhu Gui (c. 1644-1717) was commissioned to cut the blocks from which the publication was printed. It is implied that the seven-character quatrains above each illustration were composed by the emperor, but some at least were probably composed by the scholars at the court, although the text is designed in imitation of the emperor’s own calligraphy. There are two versions of the 1696 edition, apparently printed from different blocks, one of which has the seals on the illustration pages in black and the other with the seals in red. Both versions have red seals appended to the preface. While the Kangxi Yuzhi Gengzhi tu remained and still remains the best-known version of this publication, further versions were produced during the Yongzheng and Qianlong reigns. In the Qianlong version, the illustrations were revised by the painter Jiang Pu. It has been suggested that this was a single copy which was stored in the Guijishan Tang Library of the Yuanming yuan, but that in 1769 the Qianlong Emperor added his own poems to this edition and thereafter it was stored in the Jiaxuan hall.

The significance of the Gengzhi tu to the imperial family in the 18th century can be seen not only in the fact that the Qianlong Emperor composed new poems for the 1769 edition published in his reign, but that in the Yongzheng reign a 52 leaf album was produced in colour on silk in which portraits of the Yongzheng Emperor were inserted in each illustration performing one of the tasks undertaken by one of the peasants in the Kangxi version – no matter how menial. This album is preserved in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, and is illustrated in Paintings by the Court Artists of the Qing Court, The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, vol. 14, Hong Kong, 1996, pp. 74- 90, with the illustration comparable to the image on the current flask being leaf number three, shown on page 76, lower left, entitled haonou.

These imperial depictions of agriculture and sericulture, which even included the emperor himself depicted working in the fields, serve as to illustrate of the importance of the success of these activities to China as a whole and the important role of the Emperor and Empress in ensuring bountiful harvests. As the Son of Heaven the emperor was an intermediary between Heaven and Earth, and was regarded as a significant participant in all cosmic activities. If he failed to conduct the proper rituals and sacrifices, he could be seen as responsible for disasters, such as poor harvests with their concomitant effects on the empire. A major ritual carried out by the emperor each year required that he personally ploughed the first furrow of the spring season – traditionally the second day of the second lunar month – and that the Empress should personally bring him sustenance after his exertions. An anonymous imperial hand scroll entitled The Emperor ploughing the first furrow, Qingeng tu in the collection of the Musee national des Arts asiatiques-Guimet in Paris, depicts the Yongzheng Emperor plough with a golden coloured water buffalo, while the princes and high officials wait to plough in their turn (exhibited in The Very Rich Hours of the Court of China 1662-1796 – Masterpieces from Qing imperial painting, Paris, 2006). This was a ritual which fascinated European visitors to China and there are many depictions of the Qianlong Emperor ploughing the first furrow, including the famous engraving of 1786 by Isidore Stanislas Helman (1743-1806). While the emperor conducted the rituals in respect of agriculture, the empress was responsible for ensuring the success of sericulture (silk production). On an auspicious day in spring the empress was required to conduct rituals at the Temple of the Goddess of Silk Leizu, who was believed to be an empress and wife to the legendary Yellow Emperor, and who is credited with discovering sericulture and inventing the silk loom. Amongst the rituals carried out by the Qing dynasty empress was the use of a golden hook to collect mulberry leaves to feed the silk worms, after which the other ladies would also collect leaves using hooks of different materials appropriate to their status.

The inspiration drawn from the Kangxi Yuzhi Gengzhi tu and its successors can be seen in a number of different media in the 18th century. A set of porcelain plaques mounted as a folding, four-volume book was produced in the Qianlong reign. These plaques, with paired images and text plaques, were beautifully decorated in grisaille enamel, except for the two seals on each of the text plaques, which were depicted in iron red. This ‘porcelain book’, from the former Qing court collection is illustrated in Poem and Porcelain: The Yu Zhi Shi Ceramics in the Palace Museum, Beijing, 2016, no. 73. An image on one of the plaques shows a farmer standing on a tangba , harrow, drawn by a water buffalo, while another shows the farmer ploughing, both similar scenes to that seen in one of the images in the original Kangxi Yuzhi gengzhi tu, and also similar to the scenes on the current moonflask. An imperial album of paintings by Xu Yang illustrating Ten Imperial Poems on Agricultural Implements by Emperor Gaozong (reflecting the interest in farming implements evinced in the Southern Song version of the Gengzhi tu) also includes one depicting a farmer tilling his fields, in this case with a plough, which clearly also took inspiration from the Yuzhi gengzhi tu. This album leaf was included in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, exhibition Story of a Brand Name – The Collection and Packaging Aesthetics of Emperor Qianlong in the Eighteenth Century,Taipei, 2017, pp. 196-7, no. IV-14. Scenes from the Yuzhi gengzhi tu,including tilling scenes using both a plough and a harrow are depicted on a set of eight Qianlong imperial embroidered panels offered by Christie’s Hong Kong on 26 April, 2004, lot 356.

Large imperial flasks with the decoration seen on the current vessel are extremely rare, but would almost certainly have been commissioned by the emperor to celebrate a particular occasion. Two Qianlong flasks decorated in doucai technique with similar scenes have been published. One is in the Tianjin Municipal Museum, illustrated in Porcelain from the Tianjin Municipal Museum, Hong Kong, 1993, pl. 176 (fig. 2), while the other is in the Roemer Museum, Hildesheim, illustrated by Ulrich Wiesner in Chinesisches Porzellan die Ohlmer’sche Sammlung im Roemer-Museum, Hildesheim, Mainz am Rhein, 1981, pl. 57. A very similar blue and white flask is in the collection of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (fig. 3), which, like the current flask, also bears a design based upon the illustrations of the Gengzhi tu – on one side depicting a farmer using a harrow and on the other side a farmer using a plough, both implements pulled by a water buffalo, as on the current flask. As all the other decoration appears to be the same on the two vessels, it is possible that they formed part of a specially commissioned set.

fig.2. A doucai moonflask, Qianlong reign, in the Collection of Tianjin Municipal Museum.

fig. 3. Flask with Scenes of Plowing, Qianlong period (1736-1795), porcelain with underglaze blue. H: 23 1/4 in. (59 cm). Acquired by Henry Walters, 1911, 49.2015 © The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore.

On both the current flask and the Walters flask, the agricultural scene includes two wutong trees in the foreground, which do not appear in the printed Yuzhi Gengzhi tu. It is likely that the addition of the wutong trees (parasol trees, Firmiana simplex) in the foreground of this scene is not simply an artistic device to create a pleasing balance and frame the design. While the inclusion of these trees in no way detracts from the realism of the scenes, it is understood that wutong trees are the favoured perch of the phoenix - a mythical bird which only appears during peaceful and prosperous reigns and is closely connected to the ruler. The trees may therefore be a subtle compliment to the emperor and a wish for peace and prosperity. Wutong trees also provide a rebus for ‘together’, and thus unity.

Christie's. Three Qianlong Rarities - Imperial Ceramics From An Important Private Collection, Hong Kong, 30 May 2018

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_2a8420_437713933-1652609748842371-16764302136.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_83ee65_2024-nyr-22642-0954-000-a-blue-and-whi.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_15808c_2024-nyr-22642-0953-000-a-blue-and-whi.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_e54295_2024-nyr-22642-0952-000-a-rare-blue-an.jpg)