A magnificent and extremely rare polychrome wood figure of Water Moon Guanyin, Liao-Jin dynasty (907-1234)

Lot 2858. A magnificent and extremely rare polychrome wood figure of Water Moon Guanyin, Liao-Jin dynasty (907-1234); 26 in. (66 cm.) high. Estimate HKD 15,000,000 - HKD 20,000,000. Price realised HKD 30,100,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2018.

The bodhisattva is shown seated in rajalilasana, the ‘posture of royal ease’, wearing a shawl draped over the shoulders and lopped over the arms, and a scarf tied around the torso, the dhoti tied above the waist falling in graceful folds around the legs, the face is well carved with a gentle expression below the hair gathered into a chignon behind the diadem.

Provenance: Collection of Martin Erdmann (1865-1937), New York

Sold at Christie’s London, 17-18 November 1937, lot 143

Collection of F. Brodie Lodge (1880-1967), Northamptonshire

Sold at Sotheby’s London, 7 June 1988, lot 48

Eskenazi Ltd., London, 1991.

Literature: Eskenazi Ltd., London, Ancient Chinese Sculpture from the Alsdorf collection and others, London, June 1990, cover, fig. 23, and fig. 1-13

Jin Shen, Fojiao diaosu mingpin tulu; waiguo bowuguan cangpin, Zhongguo bowuguan cangpin, Zhong wai shoucangjia cangpin [Pictorial Index of renowned Buddhist sculptures: treasures preserved in overseas museums, Chinese museums, and by Chinese and overseas collectors],Beijing, 1995, fig. 377

Petra Rosch, Chinese Wood Sculptures of the 11th to 13th centuries: Images of Water-moon Guanyin in Northern Chinese Temples and Western Collections, Stuttgart, 2007, p. 244 and p. 320, fig. XXIV

A Dealer’s Hand: The Chinese Art World Through the Eyes of Giuseppe Eskenazi, London, 2012, p. 229, pl. 134.

PROPERTY FROM A EUROPEAN PRIVATE COLLECTION. WOODEN FIGURE OF THE BODHISATTVA WATER MOON GUANYIN, LIAO - JIN DYNASTY, 12TH CENTURY

Rose Kerr

Museum Expert Advisor, Hong Kong

Former Keeper of the Far Eastern Department, Victoria & Albert Museum

This attractive, contemplative sculpture is a religious image, depicting a Buddhist deity know as a Bodhisattva. Bodhisattvas were originally ordinary people, who through long meditation, prayer and a cycle of rebirths, had reached the ultimate goal of nirvana, i.e. liberation from all mental cares, and rebirth into a state of the highest happiness. But Bodhisattvas choose to turn away from that transcendental bliss, in order to return to the world to help other suffering human beings. For that reason, they hold a special place in the hearts of Buddhist worshippers.

The particular Bodhisattva is known in India as Avalokitesvara, the “Lord who looks down”, and he embodies compassion. In China he is called Guanyin, which means “comprehending the cries [of the world]”. In this figure, the cast of face with inward-turning gaze emphasises the Bodhisattva’s powers as a comforter, while the naturalistic modelling of body and dress stress nearness and accessibility. The figure is seated in a relaxed way, leaning on one arm with one leg drawn up, a posture of Royal Ease that has been identified with Water Moon Guanyin, a name taken from a Buddhist text called the Flower Garland Sutra. Flower Garland Sutra was an influential text that illuminated a cosmos of infinite, interlocking realms, existing in a state of mutual balance, without contradiction or conflict. A peaceful teaching, it argued that there is no cause and effect in the world, rather a state of mutual interfusion and complete equality.

The figure depicted is a male deity, for his bare torso is clearly visible beneath his robes. During the succeeding Ming dynasty the portrayal of Guanyin changed to that of a female divinity, because Guanyin’s merciful nature was compatible with womanly qualities, in particular the power to grant sons.

Guanyin is dressed in a form of clothing that is essentially Indian, a legacy of the religion’s transmission from India during the long-ago Han dynasty. Chinese apparel would never reveal so much of the naked body. Round his waist Guanyin wears a skirt or dhoti, consisting of a piece of material tied around the waist with a sash and extending to cover most of the legs. The Brahmanic cord is tied around his body and scarves are draped round his shoulders and across his torso, their ends moving gently in a divine wind. His hair is tied on top of his head in an elaborate chignon, with long trailing tendrils of hair, and he wears earrings in his pendant ear lobes. Round his head is a delicate crown, with a space in the middle that may originally have borne a small, seated image of the Buddha Amitabha, as was common. An elaborate necklace with dangling pendant hangs across his chest, while his arms are adorned with bangles and armlets. In the centre of his forehead is a depression that originally held a jewel, representing the third eye of divine perception. Luxurious dress and jewellery indicate that Bodhisattvas are noble figures, their attire based on the garb of Indian princes. This contrasts with the humble costume of the Buddha himself.

Wooden statues with painted surfaces were made in large numbers for Buddhist temples in north China during the 10th-13th centuries. They originally sat in a temple hall, along with other Buddhist figures of veneration. Many northern temples were as extensive as palaces, and contained a series of courtyards in which stood magnificent buildings devoted to worship, teaching and monks’ living quarters. Water Moon Guanyins with attendants were often placed back-to-back with the main Buddha image in an image hall, facing the rear, that lead into a further courtyard. Thus they protected the sanctified domain against evil spirits.

Conservation work on this sculpture reveals that the deity was probably originally designed to have a lifelike appearance.1 The figure was subsequently redecorated at least twice over the centuries. It was probably in the Ming dynasty that the appearance of the statue was completely changed to resemble gilt bronze, by applying raised patterns to the clothing and gilding the entire surface of the figure. In the late nineteenth or early twentieth century the surface of the statue was covered with thin paper that obscured details of the fine carving beneath, and was painted in rather garish colours. These several phases of redecoration were necessary because the sculpture was situated in a draughty, unheated hall, and suffered depredation from the elements. Refurbishment was carried out as an act of devotion that attracted merit by worshippers, who often paid for the work to be carried out.

Research and conservation projects on Guanyin figures in the Victoria and Albert Museum (fig. 1) and the Rijksmuseum have (fig. 2) revealed details of how the sculptures were constructed and decorated.2 These programmes provide useful points of comparison. The figure in the Victoria and Albert Museum was made of blocks of wood, jointed together. The wood came from a Paulownia species, the “Foxglove Tree”. It is likely that the Bodhisattava under discussion here was constructed in a similar manner, with his head, feet and hands being inserted into the torso. His right hand and right foot contain replacement pieces of wood.

fig. 1. A polychrome wood figure of Water Moon Guanyin, c. 1200. Purchased with Art Fund support, the Vallentin Bequest, Sir Percival David and the Universities China Committee. Photo © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

fig. 2. A polychrome wood figure of Water Moon Guanyin, c. 1100-1200. Artwork © On loan from the Asian Art Society in The Netherlands.

The V&A figure was then covered with a gesso ground of kaolin clay bound with an animal glue; a similar colourless gesso layer was discovered on the Christie’s Bodhisattva. The surfaces were painted with several layers of pigments, their hues obtained from vegetable dyes like indigo, and mineral pigments. Expressive features were added, such as the delicate hairs of beard and moustache that were revealed when the mouth area of the Christie’s image was cleaned. The original, naturalistic painting of the figures appears to have changed completely during Ming dynasty restorations, when the images were made to look like gilt-bronze. Lastly, they suffered from crude paper-overlay repairs in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century.

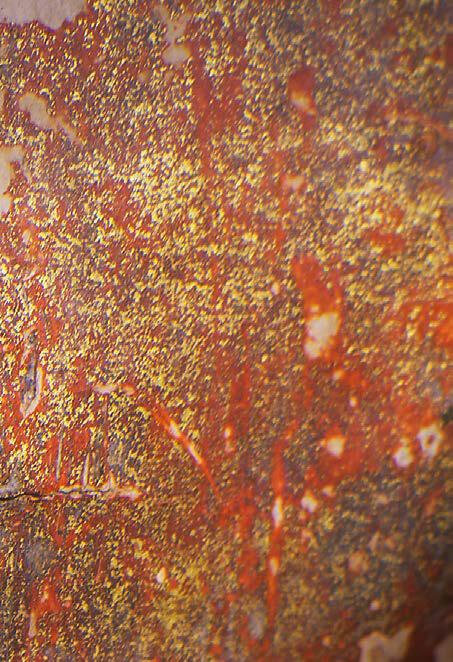

One significant feature of decoration on all three Guanyin figures (Christie’s, the Victoria and Albert Museum and the Rijksmuseum) was the embellishment of the original robes with designs of cut gold (fig. 3a & b). Investigation revealed the presence of this delicate patterning in protected areas, such as the back of folds in garments. Gold-foil was applied on Buddhist sculptures and paintings in order to give them a precious appearance, and its origins go back at least to the Northern Qi dynasty (550-577), as examples from excavations at Qingzhou in Shandong province have shown.3

fig. 3a. Traces of original cut gold on the face of the current wood Guanyin.

fig. 3b. Traces of original cut gold on the face of the current wood Guanyin.

Gold itself was not seen as mere decoration, but as a gift to Buddha. Thus the decoration of Buddhist works of art with gold and silver was a way of expressing one’s piety and devotion. Gold-foil applications on sculptures imitated gold-thread embroidery, or designs rendered in gold-foil imprints on textiles. They most likely copied not only Chinese textiles, but also those influenced by Central Asian and Indian clothing.

The application of gold-foil was a difficult process. First three layers of thin gold-foil leaves were joined together through heating, thereby creating a thicker and less easily-tearable sheet. Next, a sharp bamboo knife cut threads of gold-foil up to 3mm in width, that were applied to the painted surface, or to the gesso ground, using glue or lacquer. Geometrical patterns were built up using the gold threads, to mimic those of figured silk.4 The traces of deep red decoration with fine gold lines were found on a small area at the back, right-hand side of the Christie’s figure.

This figure was published by Petra Rosch in her book on images of Water-Moon Guanyin.5 She describes and researches images still in situ in China, and also many that were removed from temples during the 1920s and 1930s, and sent to the West. This sculpture is first mentioned in a Christie, Manson and Woods auction catalogue of 1937, when it was sold in London. The Guanyin then came into the collection of F. Brodie Lodge (1880-1967), Northamptonshire, and was later sold at a Sotheby’s sale in London in 1988. He then later made his next appearance in a 1990 catalogue of the distinguished London art dealer Giuseppe Eskenazi.6

This Water Moon Guanyin has thus travelled a long path. He was originally carved and painted for a temple in north China, at a time when the region was under the control of rulers from the north, first the Liao ( 907-1125), and then the Jin (1115-1234). Both were originally nomadic tribesmen, descended from the great tribes of Huns in the northern steppelands. Both empires became devoutly Buddhist, constructing temples and monasteries. The most important Buddhist sect of the Liao empire was the Huayan Sect, whose foundation derived from the Flower Garland Sutra. The centre of the Huayuan school of Buddhism was Shanxi province, the area where many wooden sculptures were made.

Jin dynasty rulers built on this religious tradition, adopting Buddhism as the state religion in place of Shamanism. In their turn they built impressive monasteries and nunneries, filled with religious statuary and icons. Buddhist monks had to be examined every three years, and the Buddhist community was organized down to county level. It is evident that China was lavish in its patronage of Buddhism in the 12th century, ensuring a rich legacy of temples, tombs and artefacts - including this lovely wooden statue.

1. Sophie Budden, The Conservation of a Guanyin Figure, Plowden and Smith conservation report.

2. John Larson and Rose Kerr, Guanyin, A Masterpiece Revealed (Victoria and Albert Museum, 1985). Aleth Lorne, Petra Rosch and Pauline Lunsingh Scheurleer, “The Chinese Wooden Sculpture of Guanyin. New technical and

art historical insights” in Bulletin Van Het Rijksmuseum 2002/3, pp.364-389.

3. Return of the Buddha: The Qingzhou Discoveries (Royal Academy of Art, London, 2002).

4. Petra Rosch, “Colour Schemes on Wooden Guanyin Sculptures of the 11th to 13th Centuries, with Special Reference to the Amsterdam Guanyin and its Cut Gold-foil Application on a Polychrome Ground”, in Monuments &

Sites III - The Polychromy of Antique Sculptures and the Terracotta Army of the FIrst Chinese Emperor (ICOMOS, 2001), pp.75-83.

5. Petra Rosch, Chinese Wood Sculptures of the 11th to 13th centuries. Images of Water-moon Guanyin in Northern Chinese Temples and Western Collections (ibidem Press, 2007), p.244.

6. Eskenazi Ltd, Ancient Chinese Sculpture from the Alsdorf Collection and Others, (London, 12 June – 6 July 1990), no.23.

Christie's. Contemplating The Divine - Fine Buddhist Art, Hong Kong, 30 May 2018

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F94%2F12%2F119589%2F122210217_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F49%2F54%2F119589%2F110309322_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F25%2F119589%2F110309128_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F29%2F50%2F119589%2F128346203_o.jpg)