Christie's announces highlights from its Asian Art Week series of auctions

NEW YORK, NY.- Christie’s announces Asian Art Week, a series of auctions, viewings, and events, from September 7-14. This season presents eight distinct auctions featuring over 900 lots spanning all epochs and categories of Asian Art from Chinese archaic bronzes through contemporary Indian painting. In addition to the four category sales, this season includes four thematic auctions: Qianlong's Precious Vessel: The Zuo Bao Yi Gui, a single-lot sale dedicated to a revered bronze formerly in the collection of the Qianlong Emperor; Masterpieces of Cizhou Ware: The Linyushanren Collection, Part IV, the fourth auction of a sale series of rare Chinese ceramics from an important private Japanese collection; Fine Chinese Jade Carvings from Private Collections, presenting a range of jades from five private collections; and The Ruth and Carl Barron Collection of Fine Chinese Snuff Bottles: Part VI.

The week of sales begins with Fine Chinese Paintings, led by a contemporary painting by Ma Xinle (B. 1963), Horses (estimate: $250,000-350,000) from the Collection of Steven C. Rockefeller, Jr. Additional highlights include Qi Baishi (1863-1957), Pumpkins (estimate: $60,000-100,000); and Zhang Daqian (1899-1983), Landscape (estimate: $100,000-150,000).

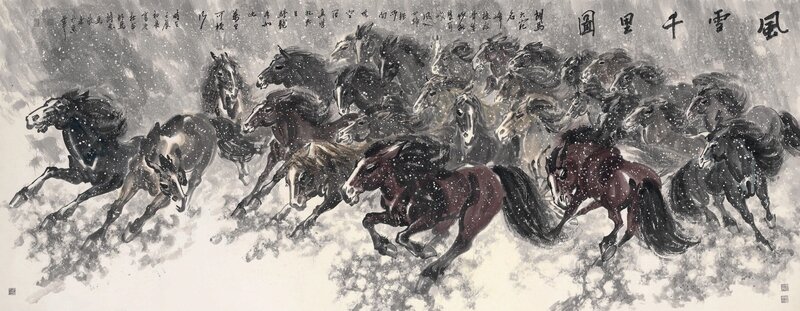

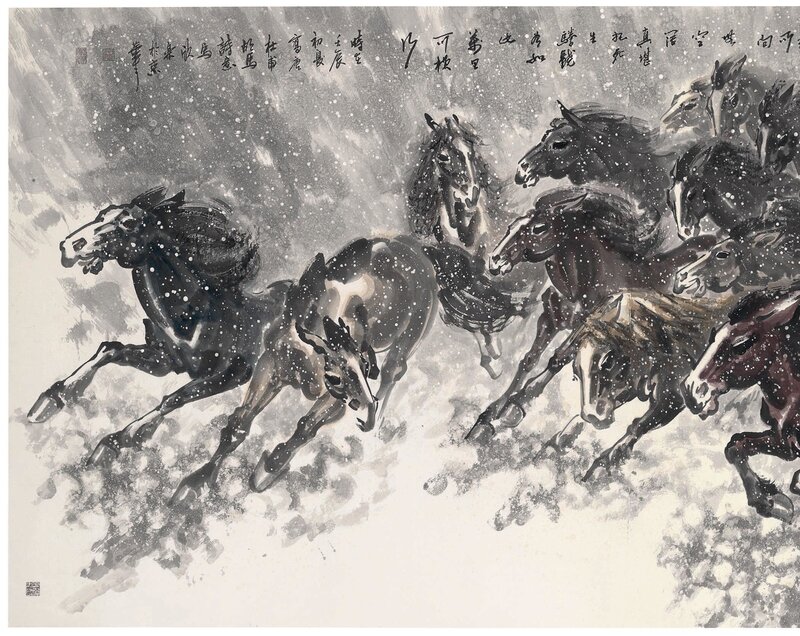

Property from the Collection of Steven C. Rockefeller, Jr. Ma Xinle (B. 1963), Horses. Scroll, mounted for framing, ink and color on paper, 55 æ x 143 in. (141.6 x 363.2 cm.) Entitled, inscribed, and signed, with two seals of the artist. Dated early summer, renchen year (2012). One collector’s seal of Steven C. Rockefeller, Jr. (born 1936). Estimate $250,000-350,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2018.

Provenance: Acquired directly from the artist.

Steven C. Rockefeller, Jr. discussing “Stampeding Horses in Snow”, International Conference Center at Yanqi Hu.

Note: Born in Xi’an, Ma Xinle received extensive artistic training beginning at a young age, when he beneftted from opportunities to observe such masters as Li Keran, Lu Yanshao, and Cheng Shifa demonstrate painting at Diaoyutai State House. He received a Master’s degree in Chinese traditional painting from the Xi’an Academy of Fine Arts and studied with such modern masters as Cheng Shifa ,Liu Wenxi, and Huang Zhou, who exerted the strongest infuence on the young artist. After he moved to the United States, Ma Xinle also studied connoisseurship with the artist-collector C.C. Wang (Wang Jiqian, 1907-2003). A very versatile artist, he also received an MFA in oil painting from Bowling Green State University in Ohio and taught watercolor and Chinese paintings for eight years. He now is active as an educator, art advisor, and cultural representative to such organizations as the Beijing Yanhuang Art Museum, the Rockefeller Art Foundation, and the Chinese Artists Association. Ma Xinle’s paintings have been widely exhibited in museums and galleries in China, the U. S. , Canada and other countries, and they can be found in museums, private and corporate collections, and government monumental buildings. In 2016 one of his paintings, The Nine Galloping Horses, was presented to Queen Elizabeth II on her 90th birthday as a state gift from the People’s Republic of China.

The frst version of this large and dramatic composition of horses racing through a blizzard of snow hangs in the main conference room at the International Conference Center at Yanqi Hu Lake, Huairou, Beijing, which has hosted such important events as the Asia-Pacifc Economic Cooperation (APEC) Forum. In 2012 Steven C. Rockefeller, Jr. commissioned Ma Xinle to complete a second but equally powerful version offered here. Mr. Rockefeller and his wife Kimberly have been enthusiastic collectors’ of Ma Xinle’s paintings for a decade. This relationship and friendship has resulted in the coordination of several Chinese art and culture exchange programs, including “Calligraphy and The Art of Business” now on view at Yale University. A key work on loan in this exhibition is Ma Xinle’s towering portrait of Yan Zhenqing (709-785) an historic Tang Dynasty calligrapher, governor and general.

Lot 38. Qi Baishi (1863-1957), Pumpkins. Hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, 53 ¿ x 13 ¿ in. (134.9 x 33.3 cm.) Inscribed and signed, with two seals of the artist. Two collector’s seals of Tsao Jung Ying (1929-2011). Estimate: $60,000-100,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2018.

Literature: Robert J. Maeda, Isamu Noguchi and the Peking Drawing of 1930, American Art, vol. 13, no.1, Spring, 1999, pp 84-93.

Jung Ying Tsao, The Paintings of Xu Gu and Qi Baishi, University of Washington Press, 1993, pp. 282-284.

Note: This composition of pumpkins, leaves and vines recalls Qi Baishi’s youth in the countryside and peasant roots. Yet, their energy and abstraction reveal the artist’s own dynamic personality and creativity. For example, the twisting tendrils of the vine are calligraphic in their creation and appearance. This painting was acquired from and published by the respected collector, connoisseur and dealer Tsao Jung Ying (1929-2011), owner of Far Eastern Fine Arts in Berkeley, California. Mr. Tsao began studying Chinese paintings from his family’s collection in his youth and during this time developed a strong interest in Qi Baishi’s paintings. Attracted to the artist’s bold and direct style but intimidated by the number of forgeries, Mr. Tsao spent the next three decades studying Qi’s works intensively. The culmination was the publication of The Paintings of Xugu and Qi Baishi in 1993. In his discussion of this painting, he concluded that it was painted at the peak of the artist’s mature style of his late 60s. “He [Qi] continued to use three broad strokes for each leaf, but before the ink had completely dried, he overlaid each of the leaves’ lobes with a single bold vein executed by wielding the brush according to the discipline of writing seal script. The fruits of this fnal stage also struck a happy medium between wide and think lines, naturalistic and abstract forms.” (Tsao Jung Ying, p. 282.)

Zhang Daqian (1899-1983), Landscape. Hanging scroll, ink and color on paper, 36 Ω x 16 æ in. (92.7 x 42.5 cm.) Inscribed and signed, with fve seals of the artist. Dated the second month, gengshen year (1980). Dedicated to J.M. Hu (1911-1995). Estimate: $100,000-150,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2018.

Provenance: J.M. Hu (1911-1995) Collection, and thence by descent.

Zhang Daqian presented this painting to J.M. Hu in honor of his seventieth birthday.

Note: Hu Hui Chun was born in 1911 in Beijing; in later years, he changed his given name to Jen Mou. The eldest son of the infuential banker Hu Chun, J.M. Hu was raised in an elegant private residence amongst his many stepbrothers and stepsisters. In keeping with tradition, he was given a rigorous background in the Chinese classics; more unusually, this was supplemented by a Western-style education, as well. He frst encountered Chinese ceramics during his student years, when he purchased a nineteenth-century brush-washer for his desk. This initial foray into collecting would become emblematic of J.M. Hu’s poignant relationship with art: even amidst the upheavals of war and the evolution of his collection, the modest brush-washer stayed with him until his death in 1995. J.M. Hu’s boyhood studies within the Chinese literati tradition greatly informed his philosophical approach to life and collecting: humble and erudite, he consistently affrmed that it was the visceral connection between a collector and his acquisitions that was of essential importance. True value, in J.M. Hu’s estimation, lay far beyond monetary worth.

J.M. Hu’s collection of Chinese ceramics provided abundant opportunity for personal scholarship and historical investigation. As early as the 1940s, he longed for a welcoming social environment where like-minded collectors could share and discuss art and objects. Two decades later, he established the Min Chiu Society in Hong Kong alongside fellow collectors K.P. Chen and J.S. Lee. A noted cultural philanthropist, J.M. Hu gifted substantial groupings from his collection to the Shanghai Museum in 1950 and 1989; many of these objects remain on view in the museum’s Zande Lou Gallery. The collector also arranged to have his family’s set of imperial zitan furniture sent to the National Palace Museum in Taipei for display, and returned the important Siming version of the Huashan Temple stele rubbing to the Palace Museum, Beijing.

Featured in a stand-alone sale, Qianlong’s Precious Vessel: The Zuo Bao Yi Gui (estimate: $4,000,000-6,000,000), is a magnificent archaic bronze gui and an exceptionally rare four-legged example formerly in the imperial collection of the Qianlong Emperor. Additional highlights across Chinese works of art include two early Tang dynasty limestone bodhisattvas offered in separate lots: a rare grey limestone figure of Avalokiteshvara, early Tang dynasty, 8th century (estimate: $1,500,000-2,500,000) and a rare grey limestone figure of Mahasthamaprapta, early Tang dynasty, 8th century (estimate: $1,500,000-2,500,000). Additionally featured is a superb selection of archaic bronzes from the MacLean Collection, Illinois, including a bronze ritual food vessel, ding, late Shang dynasty, 13th-12th century BC (estimate: $200,000-300,000).

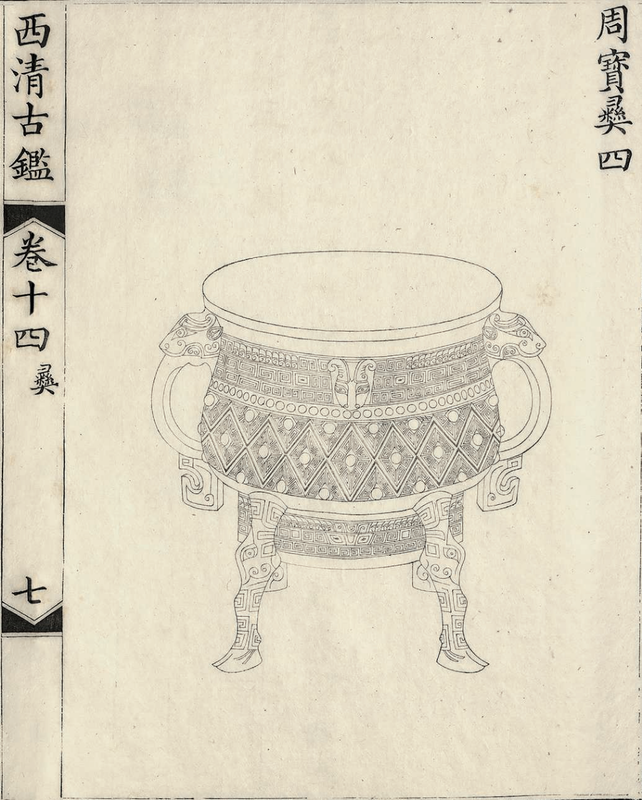

Lot 888. Qianlong's precious vessel: The Zuo Bao Yo Gui. A highly important and ectremely rare bronze ritual four legged food vessel, Early Western Zhou Dynasty, 11th-10th century BC; 7¡ in. (18.8 cm.) high, 7¿ in. (18.1 cm.) mouth diam., 3020 g. Estimate: $4,000,000-6,000,000. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

The vessel is raised on four tall hoofed legs, each decorated at the top in intaglio with a taotie mask shown in profle, above a kui dragon, the legs forming the four corners of the ring foot decorated between the legs with a quilled triple band forming a taotie mask. The body is decorated with a diamond-and-boss band between narrow borders of circles cast in thread relief, and the neck with a further quilled triple band centered on two sides by a small ram mask cast in relief and interrupted on the other two sides by a pair of handles surmounted by horned animal masks and cast at the bottom with hooked pendants. The bottom of the interior is cast with a threecharacter inscription reading zuo bao yi. The surface has an attractive, milky olive-green patina, cloth box.

Provenance: Collection of the Emperor Qianlong (1711-1799), by 1749.

Wu Dacheng (1835-1902) Collection, by 1887.

C. T. Loo & Co., New York, by 1940.

Edward T. Chow (1910-1980) Collection.

Sotheby’s London, 16th December 1980, lot 338.

Eskenazi Ltd., London, 1980.

Bella and P.P. Chiu Collection, by 1988.

Eskenazi Ltd., London.

Michael Goedhuis Ltd., New York, 1998.

Exhibited: Detroit, Exhibition of Ancient Chinese Ritual Bronzes Loaned by C.T. Loo & Co., The Detroit Institute of Arts, 18 October-10 November 1940.

New York, Exhibition of Chinese Arts, C. T. Loo & Co., 1 November 1941-30 April 1942.

Literature: By the order of Emperor Qianlong, Liang Shizheng, Jiang Pu, Wang Youdun, et al., Xiqing gujian (Mirror of Antiquities [prepared in the] Xiqing [Southern Study Hall]), Imperial Printing Ofice in the Wuyingdian (Hall of Martial Valor), Forbidden City, Beijing, 1755, vol. 14, p. 7.

Wu Dacheng, Kezhai cangqi mu (List of the Objects Collected by Kezhai [Wu Dacheng]), 1887.

Wu Dacheng, Kezhai jigulu (The Records of Collecting Antiques by Kezhai [Wu Dacheng]), 1918, vol. 7, p. 11 (inscription only).

Liu Tizhi, Xiaojiaojinge jinwen taben (Rubbings of Archaic Bronze Inscriptions at the Xiaojiaojingge Studio), 1935, vol. 7, p. 61 (inscription only).

Luo Zhenyu, Sandai jijin wencun (Surviving Writings from the Xia, Shang, and Zhou Dynasties), 1937, vol. 6, p. 19 (inscription only).

The Detroit Institute of Arts, Exhibition of Ancient Chinese Ritual Bronzes Loaned by C.T. Loo & Co., New York, 1940, no. 25.

C.T. Loo & Co., Exhibition of Chinese Arts, New York, 1941, no. 12.

Phyllis Ackerman, Ritual Bronzes of Ancient China, New York, 1945, pl. 29.

Chen Mengjia, Yin Zhou qingtongqi fenlei tulu (In Shu seidoki bunrui zuroku; A Corpus of Chinese Bronzes in American Collections), Tokyo, 1977, nos. A177 (illustration) and R363 (inscription).

Zhou Fagao, Zhang Risheng and Huang Qiuyue, Sandai jijin wencun zhulu biao (Contents of Literature of Surviving Writings from the Xia, Shang, and Zhou Dynasties), Taipei, 1977, no. 1303 (inscription only).

Zhou Fagao, Sandaijijin wencun bu (Supplements of surviving writings from the Xia, Shang and Zhou dynasties), Taipei, 1980, no. 363 (inscription only).

Sun Zhichu, Jinwen zhulu jianmu (Brief Contents of Literature of Archaic Bronze Inscriptions), Beijing, 1981, no. 1735 (inscription only).

Yan Yiping, Jinwen Zongji (Corpus of Bronze Inscriptions), Taipei, 1983, no. 1909 (inscription only).

The Institute of Archaeology, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, Yinzhou jinwen jicheng (Compendium of Yin and Zhou Bronze Inscriptions), Beijing, 1984, no. 3270. (inscription only).

Minao Hayashi, In Shu seidoki soran (Conspectus of Yin and Zhou Bronzes), vol. 1 (plates), Tokyo, 1984, p. 110, gui no. 248.

Thomas Lawton, ‘An Imperial Legacy Revisited: Bronze Vessels from the Qing Palace Collection’, Asian Art, vol. 1, no. 1, Fall/Winter 1987-8, pp. 51-79.

Jessica Rawson, The Bella and P.P. Chiu Collection of Ancient Chinese Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1988, no. 21.

Ma Chengyuan, Zhongguo qingtongqi (The Chinese Bronzes), Shanghai, 2009, p. 122, fg. 23.

Wu Zhenfeng, Shangzhou qingtongqi mingwen ji tuxiang jicheng (Compendium of Inscriptions and Images of Bronzes from the Shang and Zhou Dynasties), Shanghai, 2012, vol. 8, p. 221, no. 3922.

Giuseppe Eskenazi with Hajni Elias, A Dealer’s Hand, The Chinese Art World Through the Eyes of Giuseppe Eskenazi, London, 2012, p. 82, fg. 71.

On the Collector.

This is a collector, unusual in today’s world, of exceptional decisiveness and aesthetic acumen. His acquisitions over the years have been both intellectually impressive and the manifestation of a sparkling intuitive eye.

This bronze gui is of exceptional quality and importance, both on account of its calibre as a manifestation of Chinese bronze casting at its apogee, and the fact that it was published in 1755 in the Xiqing gujian, the Qianlong Emperor’s grand undertaking to catalogue the imperial collection of archaic bronzes.

It has been a pleasure knowing the present owner for two decades, which is a relationship that has grown as I assisted his family in assembling a frst-class collection of Chinese works of art. He has always collected with an astute awareness of historical signifcance, rarity and above all of beauty.

He is a collector interested in a wide range of works of art from various cultures, with his initial passion for bronzes ignited through his friendship with the Sackler family. Subsequently, as a founder of a number of world-leading advanced technology companies, he developed a deep appreciation for the unique achievement of early Chinese bronzes, an achievement that is so vividly expressed by the technical virtuosity and aesthetic quality of the present gui. For him, bronzes demonstrate the power of technology over the centuries to bring people together, just as today his commitment to the most exciting new technology represents his belief in the power of excellence.

Michael Goedhuis, London, 2018.

Tradition Transformed. A Western Zhou Legged gui Vessel

Apart from its bold decoration and fne patination, this magnifcent bronze gui 簋 food-serving vessel is art-historically important for its reinterpretation of the traditional gui form through the addition of four legs. As such, it joins a small handful of other legged gui vessels that were produced in the early and middle Western Zhou periods (西周早期, 西周中期).

A vessel for serving cooked millet, sorghum, rice, or other grains, this bronze gui comprises a traditional, circular gui form resting on four legs, each in the form of a hoofed animal leg. With its S-curved profle, the container portion of the vessel has a lightly faring lip, a constricted neck, and a lightly compressed globular bowl set on a circular footring. Attached to and overlapping the footring, four long legs descend to elevate the vessel. The top of each leg suggests an animal head in the form of a half-taotie mask 饕餮紋, while the shaft of each resembles an animal leg with a hoof at the bottom and a bulge at the middle representing a knee. Issuing from a stylized animal head on either side of the vessel’s neck, two opposed, vertically oriented, loop handles reconnect to the vessel at the bottom of the bowl, their curvature echoing the bowl’s full, bulging form. The bowl’s surfaces are divided into three clearly articulated decorative registers effectively separated by narrow, unembellished bands. Bordered top and bottom by a thin band of small rings, the principal decorative register, around the bowl’s bulging belly, features a diamond-and-boss pattern 方格的乳釘雷紋, while the registers around neck and footring sport so-called “animal triple bands”, which are centered on pairs of large rectangular eyes and lined by quills along the upper edges. A pair of naturalistic, horned ram’s heads enlivens the animal triple band around the neck, each head rising in relief and appearing a quarter turn from the handles. Unlike the ram’s heads at the neck and the bosses 乳釘 in the principal register, which rise in relief, the abstract decoration on the vessel legs appears in intaglio lines.

Bronze casting came fully into its own in China during the Shang dynasty 商朝 with the production of sacral vessels intended for use in funerary ceremonies. Those vessels include ones for food and wine as well as ones for water; those for food and wine, the types most frequently encountered, group themselves into storage and presentation vessels as well as heating, cooking, and serving vessels. A sacral vessel for serving offerings of cooked food, the gui first appeared during the Shang dynasty (c. 1600 BC–c. 1030 BC) and continued well into the Zhou 周朝 (c. 1030 BC- 256 BC).

Although standard vessel shapes and established decorative motifs both persisted after the fall of Shang, the people of Western Zhou 西周 (c. 1030 BC – 771 BC) quickly introduced changes, perhaps refecting slightly differing religious beliefs and ceremonial practices; in fact, some vessel types disappeared, while others became more elaborate and thus more imposing. Except for its legs, this gui foodserving vessel is conservative in shape, exhibiting the basic Shang interpretation of the vessel form. Through its transformation by the addition of the four legs, however, this vessel refects the new, post-Shang age in which it was produced.

Typically resting on a circular footring, gui vessels of the Shang dynasty claim a compressed, globular bowl, frequently with a lightly faring neck and two visually substantial, vertically oriented, loop handles. A variant vessel form with deep rounded bowl, often lacking handles but occasionally with a pair of horizontally set, loop handles, is often categorized as a yu 盂; functionally and stylistically related, both gui and yu vessels were used for serving cooked grains.1 Precise distinctions between yu and gui vessels are diffcult to defne, and, according to Jessica Rawson, “even the evidence of vessels self-named in their inscriptions is partly contradictory”. 2

The standard Shang form of the gui continued into the Western Zhou, though modifcations in both form and decoration soon ensued. The most obvious alteration to the form involved elevating the vessel, often by presenting it on an integrally cast square socle, or base,3 but occasionally by setting it on four legs, as in this excellent example. In rare instances, an entire group of vessels might be raised by placing them on a bronze altar table, known in Chinese as a jin 青銅禁, such as the example in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (24.72.1)4. The reasons for raising the vessels remain unknown but could involve changes in religious needs or ceremonial requirements, for example, or perhaps a simple desire for greater visual impact.

In discussing the present vessel, Jessica Rawson commented, “Animal-like legs on gui seem to have developed from elaborate handles used on a few gui… On later gui the elaborate handles were omitted, attention being focused instead on the legs attached to the footring, as here.”5 Early examples of legged gui vessels vary in the shape of the legs and their point of attachment. In some vessels, the legs are columnar, in others they claim a geometric shape, and in yet others they assume a zoomorphic form, whether the trunk of an elephant or the leg of an animal (as in this gui vessel). (Figs. 1-3) In some instances, the number of handles was increased from two to four, with the integrally cast legs descending from the bottom of the handles, as seen in the columnar legs of the Chen Chen Fu Yi Gui 臣辰父乙簋 in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums (1944.57.8.a-b)6 or in the columnar legs—albeit each with hoof at the bottom—of a gui that once was in the Qing Palace collection and that was sold at Christie’s, Hong Kong, in 2003.7 (Fig. 4) Over time, the legs came to be attached to the footring and occasionally were reduced in number to just three, as evinced by a gui in the collection of the Shanghai Museum,8 another in the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco (B60B893),9 and yet another in the Princeton University Art Museum (y1965-57).10 In fact, the shapely legs, their clearly defned points of attachment, and their harmonious relationship to the handled bowl they support rank the present vessel among the most aesthetically successful of the legged gui.

Fig. 1 Bo Gui, early Western Zhou dynasty. The Capital Museum Collection. After Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji (Complete Collection of Chinese Bronzes), vol. 6: Western Zhou 2, Beijing, 1997, no. 15.

Fig. 2 Ban Gui, middle Western Zhou dynasty. The Capital Museum Collection. After Zhongguo qingtongqi quanji (Complete Collection of Chinese Bronzes), vol. 6: Western Zhou 2, Beijing, 1997, no. 15.

Fig. 3 Zi Gui, early Western Zhou dynasty. The National Museum of China Collection. After Wenwu, 1959, no. 12, p. 59.

Fig. 4 Bronze four-legged gui, early Western Zhou dynasty. Christie’s Hong Kong, 7 July 2003, lot 624; now in the Compton Verney Collection.

Although the taotie mask 饕餮紋 was the decorative motif most frequently encountered on bronze ritual vessels from the Shang dynasty, other motifs were popular as well, including long-tailed birds, dragon-like forms, and even snakes. Apart from those “representational” motifs, a variety of abstract, non-representational, geometric motifs also appear on Shang bronzes, from interlocking T-forms and zig-zag, or chevron, patterns to vertical ribs and diamond-and-boss patterns. Long forgotten, the meaning of such decorative schemes, if any, has been lost to the mists of time for both geometric and representational types.

Many such motifs continued into the Western Zhou, the “representational” motifs often showing a distinct evolution, the abstract motifs generally remaining more traditional and conservative, even if presented in slightly new combinations and contexts. The late Shang gui with diamond-and-boss pattern, bordered above and below by a narrow band of small rings, that sold at Christie’s, New York on 22-23 March 2012 (lot 1507) stands as the model from which the related Western Zhou gui vessels derive.11 And the early Western Zhou gui with diamond-and-boss pattern, again, bordered top and bottom by a narrow band of small rings, that sold at Christie’s, New York on 17 March 2017 (lot 1005) demonstrates the Western Zhou continuation of the Shang type while also perfectly representing the type of vessel to which legs were added to create the present gui vessel.12

Used in ceremonies honoring the spirits of deceased ancestors, bronze sacral vessels from the Shang and early Western Zhou periods often bear short, dedicatory inscriptions. The so-called bronze-script characters 金文字 are related to contemporaneous oracle-bone characters 甲骨文字—that is, characters carved on ox scapulae 牛肩胛骨 or turtle plastrons 龜腹甲 as part of a divination process employed in Shang times—and they are the direct ancestors of modern written Chinese.

Integrally cast, a short inscription of three characters arranged in a single column appears on the foor of this gui; it reads zuo bao yi 作寳彜 and may be translated “Made [this] precious vessel”. As the name of the maker—more properly, the name of the person for whom the vessel was made—does not appear in the inscription, we cannot know in whose funerary ceremonies this vessel was used. Though likely no more than coincidence, the famous Zuo Bao Yi Gui 作寳彜簋 formerly in the collection of Julius Eberhardt (of Vienna, Austria) and, before that, in the collection of H.E. A.J. Argyropoulos (of Athens, Greece), bears the same inscription.13

The Hong Gui 妅簋 in the collection of the Shanghai Museum is the vessel most closely akin to the present gui;14 in fact, the two vessels are exceptionally close in date, style, and general appearance. (Fig. 5) Dating to the early Western Zhou period and standing on four clawed, rather than hoofed, zoomorphic legs, the Hong Gui claims a traditional gui form, with compressed globular bowl with a circular footring below and a lightly faring neck with thickened lip at the top. Its midsection boasts a diamond-and-boss pattern, while the band around the neck sports a pattern of snakes 蛇紋 set against a leiwen 雷紋 ground; the footring is undecorated. Instead of simple loops, the handles of the Hong Gui have elephant heads at the top with descending trunks that curve elegantly outward at the end but that are anchored to the bottom of the bowl by a strut. The inscription on the foor of the Hong Gui reads Hong zuo bao zun yi 妅作寳尊彜 and may be translated “Hong made [this] precious vessel”. Based on the context, the first character, which is read “Hong” 妅, is believed to be a personal name—i.e., based on its occurrence as the frst word in this formulaic inscription and on its placement immediately before the verb 作zuo (made). Alas, so far as is known, Hong is otherwise unrecorded, so Hong’s identity and life dates and circumstances remain unknown.

Fig. 5 Hong gui, early Western Zhou dynasty. The Shanghai Museum Collection. After Chen Peifen, Xia Shang Zhou qingtongqi yanjiu (Research on Xia, Shang, and Zhou Bronze Vessels), Shanghai, 2004, vol. 4, pp. 84-85, no. 231.

The present gui claims the most impeccable, the most impressive of pedigrees. By 1749 it was in the Qing Imperial Collection, one of the bronzes collected by the Qianlong Emperor 乾隆 (r. 1736–1795); it is published in his Xiqing gujian 西清古鉴, the forty-volume catalogue of the ancient bronzes in his collection (vol. 14, p. 7). Renowned collector Wu Dacheng 吴大澂 (1835–1902) had acquired it prior to 1887, and it is recorded in catalogue Kezhai Jigulu 愙齋集古錄 (vol. 7, p. 11), which was published posthumously in 1918. In the twentieth century this gui was owned by celebrated collector Edward T. Chow 仇焱之15, 16 and subsequently by acclaimed collectors Bella and P.P. Chiu (趙氏山海樓所藏古代青銅器).17

The present Zuo Bao Yi Gui as documented in the Xiqing gujian (Mirror of Antiquities [prepared in the] Xiqing [Southern Study Hall]), Imperial Printing Ofice in the Wuyingdian (Hall of Martial Valor), Forbidden City, Beijing, 1755, vol. 14, p. 7. Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing. Image copyright © The Palace Museum. Library

Featured in exhibitions in Detroit and New York, this gui has also passed through the galleries of such prominent art dealers as C.T. Loo 盧芹齋 (1880–1957), Eskenazi Ltd. and Michael Goedhuis Ltd.

A strikingly beautiful bronze and one with an exceptionally distinguished provenance, this gui is art-historically important for its reinterpretation of the traditional gui form through the addition of four legs. In fact, it is a major monument in the history of Western Zhou bronzes.

Robert D. Mowry

Alan J. Dworsky Curator of Chinese Art Emeritus, Harvard Art Museums, and Senior Consultant, Christie’s.

1 Ma Chengyuan, Ancient Chinese Bronzes (Oxford, Hong Kong, New York: Oxford University Press), 1986, ed. Hsio-yen Shih, p. 192.

2 For a discussion of this confusing nomenclature, see: Jessica Rawson, Western Zhou Ritual Bronzes from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, vol. IIB (Washington, DC: The Arthur M. Sackler Foundation, and Cambridge, MA: Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University), 1990, pp. 454-459, no. 59.

3 For an example, see the Western Zhou gui in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums (1944.57.1), published in Chen Mengjia, Yin Zhou Qingtongqi Fenlei Tulu (A Corpus of Chinese Bronzes in American Collections) (Tokyo: Kyuko Shoin), 1977, A 219. 陳夢家, 殷周靑銅器分類圖錄 (東京: 汲古書屋), 1977, A 219. Also see: https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/203788?position=31. Also see the famous Zuo Bao Yi Gui 作寳彜簋 formerly in the collection of Julius Eberhardt (of Vienna, Austria) and, before that, in the collection of H.E. A.J. Argyropoulos (of Athens, Greece): Regina Krahl, Sammlung Julius Eberhardt: Frühe chinesiche Kunst / Collection Julius Eberhardt: Early Chinese Art (Hong Kong: Magnum Ltd.), 2004, vol. 1, pp. 96-97, no. 39, translated by Stefan B. Polter (bilingual, German and English); also see: Sotheby’s, New York, Magnifcent Ritual Bronzes, 17 September 2013, lot 3.

4 Jessica Rawson, The Bella and P.P. Chiu Collection of Ancient Chinese Bronzes (Hong Kong), 1988, p. 66, no. 21. 趙氏山海樓所藏古代青銅器 (香港), 1988, 66 頁, no. 21.

5 See: Chen Mengjia, Yin Zhou Qingtongqi Fenlei Tulu, A 230; Hayashi, Minao, In Shu Jidai Seidoki no Kenkyu [Research on Shang and Zhou Bronzes] (Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan), Showa 59 [1984], vol. 1, In Shu Seidoki Soran [A Compendium of Shang and Zhou Bronzes], p. 102, no. 177. 林巳奈夫, 殷周時代靑銅器の硏究 (東京: 吉川弘文館), 昭和59 [1984], 殷周靑銅器綜覽, 1, 102頁, no. 177; Jessica Rawson, Western Zhou Ritual Bronzes from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, p. 469, fg. 61.4. Also see: https://www.harvardartmuseums.org/collections/object/204107?position=0

6 See: Christie’s, Hong Kong, The Imperial Sale: Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art, 7 July 2003, lot 624; Hayashi, Minao, In Shu Jidai Seidoki no Kenkyu, vol. 1, p. 108, no. 235. 林巳奈夫, 殷周時代靑銅器の硏究, 1, 108頁, no. 235.

7 See: Chen Peifen, Xia Shang Zhou Qingtongqi Yanjiu: Shanghai Bowuguan Cangpin (Research on Bronzes from the Xia Shang and Zhou Dynasties: Collection of the Shanghai Museum (Shanghai: Shanghai Guji Chubanshe), 2004, 1st ed., vol. 4, pp. 86-87, no. 232. 陳佩芬. 夏商周靑銅器研究: 上海博物館藏品 (上海: 上海古籍出版社), 2004, 第1版, 第2編 [v. 3-4], 86-87頁, no. 232.

8 See: Hayashi, Minao, In Shu Jidai Seidoki no Kenkyu, vol. 1, p. 109, no. 237. 林巳奈夫, 殷周時代靑銅器の硏究, 1, 109頁, no. 237.

9 See: Hayashi, Minao, In Shu Jidai Seidoki no Kenkyu, vol. 1, p. 119, no. 305. 林巳奈夫, 殷周時代靑銅器の硏究, 1, 119頁, no. 305.

10 See: Christie’s, New York, Fine Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art (Part II), 22-23 March 2012, lot 1507.

11 Christie’s, New York , Fine Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art, 17 March 2017, lot 1005.

12 See: Regina Krahl, Sammlung Julius Eberhardt: Frühe chinesiche Kunst / Collection Julius Eberhardt: Early Chinese Art, vol. 1, pp. 96-97, no. 39; also see: Sotheby’s, New York, Magnifcent Ritual Bronzes, 17 September 2013, lot 3.

13 See: Chen Peifen, Xia Shang Zhou Qingtongqi Yanjiu, vol. 4, pp. 84-85, no. 231. 陳佩芬. 夏商周靑銅器研究, 第2編 [v. 3-4], 84-85頁, no. 231.

14 For information on Edward T. Chow (1910–1980), see: https://www.freersackler.si.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/09//Chow-Edward.pdf

15 The Edward T. Chow collection was dispersed by Sotheby’s through auctions in Hong Kong and London on 25 November 1980, 16 December 1980, and 19 May 1981. This gui vessel was sold at Sotheby’s, London, on 16 December 1980; see: Sotheby’s, London, The Edward T. Chow Collection – Part Two: Early Chinese Ceramics and Ancient Bronzes, 16 December 1980, lot 338.

16 For information on the Chiu collection, see: Jessica Rawson, The Bella and P.P. Chiu Collection of Ancient Chinese Bronzes (Hong Kong), 1988. 趙氏山海樓所藏古代青銅器(香港), 1988.

17 For information on the Chiu collection, see: Jessica Rawson, The Bella and P.P. Chiu Collection of Ancient Chinese Bronzes (Hong Kong), 1988. 趙氏山海樓所藏古代青銅器(香港), 1988.

Highlights of the Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Works of Art sale are led by an important bronze group of seated Shiva and Uma, South India, Tamil Nadu, late Chola-early Vijayanagara period, late 13-early 14th century (estimate: $600,000-800,000); an 18th century thangka of Scenes from the Life of Milarepa, Eastern Tibet (estimate: $250,000-350,000); and a thangka of Amitabha from the Xumi Fushou Temple, Qianlong period, 1779-80 (estimate: $150,000-250,000).

The South Asian Modern + Contemporary sale features masterpieces by modern Indian painters, led by Tyeb Mehta (1925-2009), Diagonal XV (estimate: $1,500,000-2,000,000) and Akbar Padamsee (B. 1928), Rooftops (estimate: $800,000-1,200,000), a monumental painting from the artist’s gray period. Additional highlights include Manjit Bawa’s Untitled (Acrobat) (estimate: $600,000 – 800,000) and Francis Newton Souza’s seminal Family (estimate: $600,000 – 800,000), among other important paintings by the artist. The auction also includes important early works by Syed Haider Raza, Vasudeo S. Gaitonde and Maqbool Fida Husain along with an impressive collection of works in various mediums by Nasreen Mohamedi

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F60%2F34%2F119589%2F128961949_o.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F07%2F26%2F119589%2F127133936_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F48%2F119589%2F126810549_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F08%2F30%2F119589%2F126109859_o.jpg)