Su Shi was born into a literary family in 1037. At the age of 19 he passed the highest-level civil service examinations with flying colours, and was marked out as a rising star within the world of officialdom. His lucid, eloquent essays greatly impressed Emperor Renzong (1010-1063) and by the time the young Emperor Shenzong (1048-1085) ascended to the throne in 1067, Su Shi was a respected figure among scholar-officials at court.

One of 12 leaves from the album Stories of Su Dongpo by Zou Yigui (1686-1772), showing Su Shi when he was 66 years old. Sold for HK$437,500 on 28 May 2012 at Christie’s in Hong Kong. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

Tensions existed between rival political factions within the imperial court, however, and in 1071 Su Shi fell foul of this factionalism and left the capital to take up a post in Hangzhou. Over almost a decade, he held a variety of government positions in prefectures including Mizhou, Xuzhou and Huzhou.

In 1079, Su Shi was arrested and put in jail. It is thought that the reason for his punishment and subsequent banishment were private verses he had written that mildly satirised the reformist movement, which held sway at court at the time.

‘When he came out in 1080 he was a different man,’ explains Zhou. ‘He was more introspective and started to shy away from politics, and began instead to contemplate on life and philosophy. He was reading Confucius and the Book of Changes [an ancient Chinese text], and writing a lot of poetry.’

Su Shi was exiled to provincial Huangzhou, where he lived in relative poverty. He built a farm in the foothills of what became known as the Eastern Slope (Dongpo), and began to call himself Master of the Eastern Slope (Su Dongpo). For all the hardships he experienced in exile, it was during this period that he produced some of his most well-known verses.

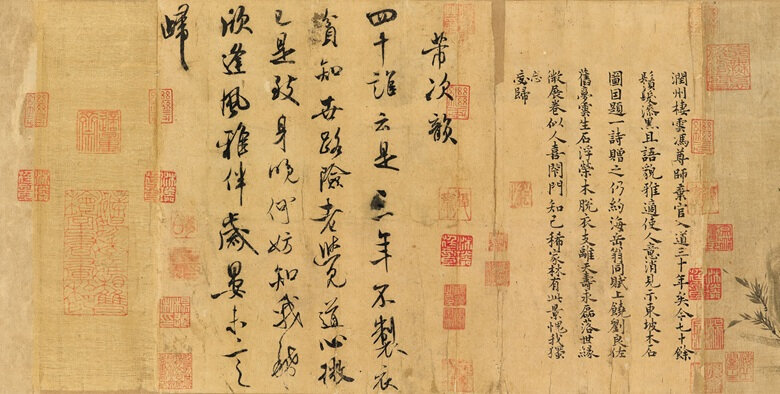

The Cold Food Observance, written during his exile to Huangzhou in 1082, then later transcribed into a work of calligraphy. It is widely hailed as the finest surviving example of Su Shi’s celebrated calligraphy. Photo: The Collection of National Palace Museum.

Frustrated with the court and living in exile, Su Shi’s works from this period ‘often conveyed a sense of desolation’, says Kim Yu, Christie’s International Senior Specialist in Chinese Paintings. ‘The artworks he created were different from those artisans, craftsmen or professional painters of the Imperial Academy. The bamboo plant and rocks, painted with brushstrokes that twist and turn, give a real air of elegance and grace. The lines may seem simple and yet they are incredibly varied and expressive.’

In 1086, Su Shi was recalled to the capital. During his absence, a power shift had taken place with the ascension of a dowager Empress who had a more sympathetic view of the conservative faction of which Su Shi was by then among the most senior living embodiments.

Su Shi was banished for the second time in 1094, being sent to Huizhou (in present-day Guangdong province) and Danzhou. During the Song dynasty, this provincial, malaria-ridden backwater would have been seen as a death sentence. Su Shi survived, however, and was pardoned in 1100, whereupon he was posted to Changzhou. He died the following year, while en route to his new assignment.

Today, Su Shi is recognised as one of the eight great prose masters of the Tang and Song, and one of the four Song masters of calligraphy. His poems, including At Red Cliff, Cherishing the Past and Prelude to the Water Melody, have become embedded in Chinese culture, inspiring landscape paintings and poetic illustrations throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties. His calligraphy has been copied, studied and collected for centuries.

Su Shi’s ideas on what it was to create an image, and the relationship of the image to the internal psychology of the painter, were revolutionary, and can be seen as a launchpad for painting as a non-representational, psychologically driven process. It was Su Shi who first began to explore concepts of artistic practice as the outward expression of the artist’s interior experience.

The painting in ink on the handscroll offered at Christie’s in November is one of only a handful of extant paintings by Su Shi.

Similarly revolutionary was Su Shi’s approach to brushwork. Other contemporary painters pursued a representational style that involved great detail and strong delineation. But Su Shi’s brushwork is impressionistic and spare. Writing on the principles by which to judge the highest class of painting, Su Shi once declared, ‘If one discusses painting in terms of formal likeness, one is no different from a child.’ For him, there was painting in poetry and poetry in painting.

‘There is a saying in Chinese art history that “ink has five colours”,’ says Zhou. ‘Ink has all that you need to depict the external world and to express yourself and whatever your artistic impulses have to say. Wood and Rock is a true embodiment of the artist’s state of mind at the time, which you can see so palpably in the painting.’

Ancient rocks and withered trees were subjects that were close to Su Shi’s heart. In Chinese iconography the withered tree has been imbued with many different meanings. It is associated with notions of surviving difficult situations, such as the one Su Shi found himself in, but still being able to grow tall.

Wood and Rock is inscribed with the poetry of Su Shi’s friend Mi Fu (1051-1107), which was probably added at a later date. Like Su Shi, Mi Fu was a celebrated poet, calligrapher, painter and statesman. For Su Shi, expressing affinity through the giving and exchanging of painting and verse in the form of calligraphy was a means of building networks of cultural capital.

The ink traces on this scroll offer insights into abstracted ideas of how Su Shi and Mi Fu thought and conceived of art, but also illuminate how these exceptional men of the 11th century understood each other. They are, therefore, tangible representations of the relationships between cultural giants of the distant past.

Mi Fu’s verse on the scroll interprets his friend’s painting of a withered tree as an intimate expression of oneself at an old age. The pathos in Mi Fu’s lament certainly resonates with what is known of Su Shi’s experiences in exile. In Mi Fu’s other writings, he speaks of how Su Shi condensed his emotions in the turns of his brush and the construction of his rocks and trees.

‘What Su Shi did, and what is palpable, tangible and legible in Wood and Rock,’ says Chinese Paintings specialist Malcolm McNeill, ‘was to replace illusion with something that, to his own understanding, was very much more psychologically raw and direct. In the elegant curves across the rock, every mark from each bristle coated in dry unsaturated ink creates a sense of this.’

And that, says Alastair Sooke, is Su Shi’s ‘gift to art history’ — the sense of an artist’s inner psychology being appropriate subject matter for art.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F34%2F12%2F119589%2F122049747_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_d8802e_440367117-1657711318332214-11984536568.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.over-blog.com%2Ft%2Fcedistic%2Fcamera.png)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_e64568_440367995-1657703268333019-41468471616.jpg)