Christie's sale celebrates pioneering Italian identity with masterpieces of 20th century Italian art

Lot 115. Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio, signed and titled 'l. fontana "Concetto spaziale" "LA FINE DI DIO"' (on the reverse, oil and glitter on canvas, 178 x 123cm. Executed in 1963. Estimate on request. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

LONDON.- During London’s Frieze week, Christie’s will present the second year of Thinking Italian, a sale concept that celebrates the eclecticism, rebellious iconoclasm, and sheer creativity of Italian art. This is the second edition of Thinking Italian, a showcase of the very best Italian Art of the 20th Century, which will follow Christie’s Post-War and Contemporary Art Evening Auction on 4 October 2018, and preludes the sale Thinking Italian: Design, scheduled in London on 17 October, which will explore the eclecticism, rigour, and creativity of 20th Century Italian design. From Umberto Boccioni and Giorgio Morandi to Alberto Burri, Lucio Fontana and Salvatore Scarpitta, the sale presents a tightly curated selection of artists who paved the way for many of the artistic developments in the latter decades of the 20th century. Furthermore, this auction celebrates the ongoing 50th anniversary of the Arte Povera movement with strong selection of works by Alighiero Boetti, Giuseppe Penone and Michelangelo Pistoletto. Highlights will be showcased in London from 28 September to 4 October 2018.

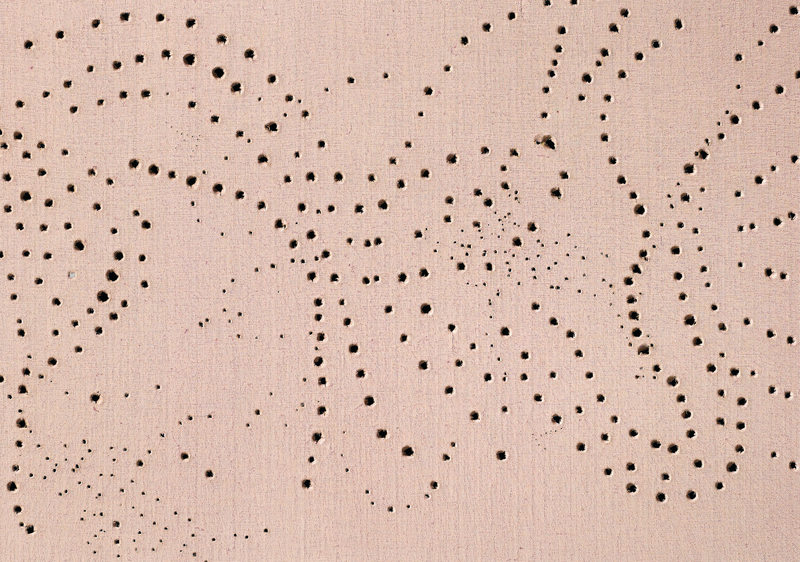

Leading the auction is Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio (estimate on request). Otherworldly, monumental and profoundly universal, this work is perhaps the most lyrically and deliberately composed work of Fontana’s rare and career-defining series. Composed of seemingly sparkling, constellation-like trails of buchi, it is interspersed with larger, primal punctures that penetrate the canvas with a visceral urgency. Works from this renowned series are today housed in museum collections across the world, including the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid, and the Museum of Contemporary in Tokyo. Equally high in museum-quality, Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio comes with distinguished provenance. Following its creation, this work entered the legendary collection of Philippe Dotrémont, a Belgian businessman who was devoted to 20th Century art, amassing a collection that encompassed masterpieces by the leading masters of modern and post-war art; including Matisse, Kandinsky and Léger, as well as Rothko and Still.

Lot 115. Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio, signed and titled 'l. fontana "Concetto spaziale" "LA FINE DI DIO"' (on the reverse, oil and glitter on canvas, 178 x 123cm. Executed in 1963. Estimate on request. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

Provenance: Philippe Dotrémont Collection, Brussels.

Renée Lachowsky Collection, Brussels.

Private collection, Europe.

Anon. sale, Sotheby's, London, 6 February 2003, lot 4.

Private Collection.

Anon. sale, Christie's New York, 12 November 2013, lot 19.

Private Collection.

Acquired from the above by the present owner.

Literature: E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana: catalogue raisonné des peintures, sculptures et environnements spatiaux, vol. II, Brussels, 1974, no. 63 FD 24 (illustrated, p. 137).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana: catalogo generale, vol. II, Milan, 1986, no. 63 FD 24 (illustrated, p. 469).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana: catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, vol. II, Milan, 2006, no. 63 FD 24 (illustrated in colour p. CCXXIII; illustrated, p. 660).

Exhibited: Brussels, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lucio Fontana, 1972, no. 66 (illustrated in colour, unpaged).

Lucio Fontana, 1963. Photo: Lothar Wolleh © Oliver Wolleh, Berlin.

Note: Otherworldly, monumental and profoundly universal, Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio (FD 24) is one of Lucio Fontana’s rare and career-defning series La fine di Dio. A complex and all-encompassing body of work, La fine di Dio is a group of thirty-eight, ovoid-shaped paintings of identicalsize and varying monochrome colour that Fontana executed over an eighteen-month period, from the beginning of 1963 through 1964, for three different exhibitions held consecutively in Zurich, Milan and Paris. Widely regarded as Fontana’s magnum opus, this series emerged as the aesthetic and conceptual zenith of the artist’s movement, Spatialism; serving as the ultimate culmination of his career-long desire to create an art form that could transcend the earthbound nature of matter and embody an infinite, immaterial and spiritual dimension. As such, it was with La fine di Dio that Fontana gained ultimate artistic freedom, triumphantly concluding his career-long interrogation of matter and material, space and light, to create a new form of art that perfectly befit the dawn of the new Space Age. Here, Fontana succeeded in unifying the relationship between time, gesture and eternity, conveying the constant transmutation of material into space, as well as the existential angst of man existing within the vast and unknowable void of space.

Neither painting nor sculpture, simultaneously a three-dimensional object and an immaterial, transcendent portal that invokes the fourth dimension and the boundless, unknowable depths of the universe, Concetto spaziale, La Fine di Dio is, like the rest of the series, a holistic object which, with its archetypal, regenerative and mystical ovoid or egg shaped form, also serves to embody the unknowable, unfathomable entity of the universe. A perfect, unending form that embodies birth, evolution, death and resurrection, it therefore serves to represent the beginning, end and entirety of existence itself. With the addition of the seemingly comprehensible yet insistently elusive title, ‘The End of God’, a statement at once shockingly iconoclastic, deeply profound and poetic, Fontana pronounced in one exultant body of work, the end of the centuries long evolution of Western painting and the beginning of a new era of art and thought. ‘For me’, he wrote, ‘La fine di Dio signify the infinite, something inconceivable, the end of figurative representation, the beginning of nothing’ (Fontana, quoted in E.Crispolti, Lucio Fontana: catalogo generale, vol. 1, Milan, 1986, p. 73).

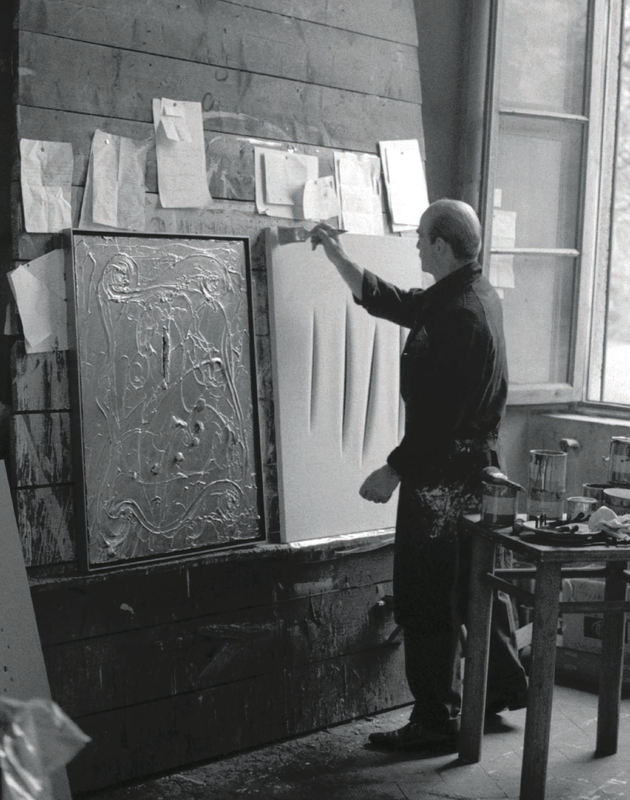

Lucio Fontana in his studio, Paris. Photo: Shunk-Kender © J.Paul Getty Trust. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles,

(2014.R.20). Gift of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in memory of Harry Shunk and Janos Kender. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2018

Occupying a supreme position within Fontana’s oeuvre, La Fine di Dio also stands as a timeless and singular expression of the post-war era, encapsulating the complex, contradictory and multivalent sentiments of an epoch defined by convulsive change, pioneering progress, conflict and existentialist crisis. As man conquered the earth’s atmosphere and reached the hitherto inconceivable realm of space, and scientific and technological discoveries changed the face of human thought and understanding, so Fontana created a strange, enigmatic and prophetic object that reflected the unknowable, visionary spirit of the times, and indeed, foreshadowed man’s physical experience of it. Composed of seemingly sparkling, constellation-like trails of buchi, interspersed with larger, primal punctures that penetrate the canvas with a visceral urgency, Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio (FD 24) is perhaps the most lyrically and deliberately composed work of this series. Unlike other works of the group, the variously formed buchi create a deeply poetic topography, spread amidst the oval plane with arhythmic harmony and a graceful beauty unique within this series. Clustered in tight formations, drifting in delicate, celestial single-line streams, or splitting the surface in violent, visceral ruptures rent open by Fontana’s hands, these emancipatory and revolutionary gestures evoke both earthly and astral planes, their placement seemingly created not by the artist but by time and space itself. Indeed, the compositional beauty of the surface surpasses any sense of the violence that bore its creation; it is no longer solely an object but appears like a timeless, mysterious sign from another world or a relic from another time. Around the perimeter of this galaxy-like orb runs a single oval outline that charts round the myriad materializing and dissolving buchi, which appear ever expanding, just like the universe itself.

Fontana had first painted Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio – at 178 cm high it is the height of the artist himself, and of the average male of the time, thus creating a revelatory, wholly immersive experience for the viewer – with his principal hue of bright, fresh pink monochrome oil paint, before covering this base with otherworldly copper-hued lustrini (‘glitter’), thereby creating an ever-changing and constant array of celestial reflections across the expansive plane. This rare combination of pink oil paint and copper lustrini lends this work a particular and unique effect. At once inherently earthbound – appearing like a piece of primeval matter emitted from the birth of the earth, its riven, shimmering surface like swelling volcanic magma, or a primordial landscape imprinted with man’s first gestures – it is at the same time insistently cosmological. Sprinkled with what could be lunar dust or the dissolving matter of an asteroid trial, this work is a cosmic splendour; an abstract evocation of far-of, constellation-filled galaxies, undiscovered planets, and elliptical orbits enlivened and invigorated with a subtle, yet alluring iridescent brilliance.

While works from this renowned series are today housed in museum collections across the world, including the Centre Pompidou in Paris, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofa in Madrid, and the Museum of Contemporary in Tokyo, Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio has a distinguished provenance, having remained largely unseen since 1963. Following its creation, this work entered the legendary collection of Philippe Dotrémont, a Belgian businessman who was devoted to 20th Century art, amassing a collection that encompassed masterpieces by the leading masters of modern and post-war art; including Matisse, Kandinsky and Léger, as well as Rothko and Still.

Lucio Fontana in his studio, circa 1963. Photo: Shunk-Kender © J.Paul Getty Trust. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles,(2014.R.20). Gift of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in memory of Harry Shunk and Janos Kender. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2018

GENESIS: The genesis of La Fine di Dio series dates to January 1963. ‘I’m incubating a series of paintings’, Fontana wrote to Enrico Crispolti, referring to this group for the first time, ‘that I would like to call the End of God’. ‘If you happen to be in Milan, come and see me’, he continued, clearly aware of the significance of this new body of work, ‘I’d like to discuss them with you, and if we agree, you could write a critical essay on them’ (Fontana to E. Crispolti, 17 January 1963, in E. Crispolti, ed., Lucio Fontana: Fine di Dio, Florence, 2017). The inspiration, Fontana explained in an interview of the same year, had supposedly come from a commission to illustrate the Bible, but instead of ‘visualising old things’, Fontana came up with these new spatial concepts (P. Gottschaller, Lucio Fontana: The Artist’s Materials, Los Angeles, 2012, p. 107). Anticipating his large egg-shaped canvases however, Fontana had already begun a small series of pen and ink drawings with the inscription ‘la fnedidio’ in as early as 1960 (see for example 60-61 DSP 116). Indeed, as with the majority of his defining cycles of work, Fontana conceived the initial concept on paper, creating what Luca Massimo Barbero has described as ‘diagrams of thought’, studies that served as, ‘a storage space of ideas, where Fontana works on the sign’ (L. Massimo Barbero, ‘The Oils. Pattern, Form and Frame: The Lexicon of the Fine di Dio’, in E. Crispolti, ed., op. cit., p. 72). These insightful pages see the artist eagerly experimenting with the oval format, filling these embryo like forms with tangled webs of lines that can be now be recognised as overriding placement of holes.

By the beginning of the 1960s, Fontana had already mastered Spatialism, the innovative movement he had founded in 1947. Interplanetary travel and the galactic accomplishments of the era fascinated the artist, as did technological innovations and Einstein’s concept of a space-time continuum: a fourth dimension of limitless, unfathomable space. In the face of these explosive developments, the destiny of painting, particularly the fate of the brushstroke was, in the eyes of Fontana and his colleagues, outmoded, antiquated and archaic.

Fontana understood that the artist, like the scientist, had to compete with a vision of the world exclusively comprised of time, matter, energy and above all, the pervasive void of deep space. Faced with this reality, Fontana called for artists to embrace this revolutionary stage of man’s evolution and produce a new, spatial art that expressed the extraordinary developments of science and space travel. ‘I assure you’, Fontana had stated in 1949, ‘that on the moon they will not be painting, but they will be making Spatial art’ (Fontana, quoted in S. Petersen, Space-Age Aesthetics: Lucio Fontana, Yves Klein, and the Postwar European Avant-Garde, Pennsylvania, 2009, p. 6).

It was with the buchi and subsequently the tagli that Fontana realised these conceptual aims. By perforating and penetrating through the previously inviolable surface of the canvas itself, Fontana succeeded in incorporating real space into his artwork, integrating slithers of darkness that served as philosophical metaphors for the infinite cosmic realm in which the earth had been found to exist. This for Fontana represented the final frontier in art: his incisions transformed the two-dimensional surface of the canvas into a multi-dimensional object that could exist within the limitless parameters of space and time: a Spatial concept.

Yet, by the early 1960s, as the post-war era was dramatically unfolding, man’s relationship with these radical innovations was changing. With Yuri Gagarin’s first voyage into space in April of 1961, the concept of space changed from being an intangible, unimaginable, near fantastical concept to something suddenly much more real and comprehensible. From seeking to embody the wondrous enigma and idealistic fascination for the cosmos, Fontana began to focus on the real, physical experience of this new realm and the existential questions that this advancement threw up. ‘Space is no longer an abstraction’, he explained, but has become a dimension which man can even inhabit, violating it with jets, with Sputniks, with space ships. It is a human dimension that can generate physiological pain, a terror in the mind, and I, in my most recent canvases, am trying to give form to this sensation’ (Fontana, quoted in L. Massimo Barbero, Lucio Fontana: Venice/New York, exh. cat., Venice & New York, 2006-2007, p. 24).

Embracing material once more in the Olii, a cycle defined by lavish, thick monochrome oil painted surfaces that are rent open with visceral, oozing, corporeal ruptures, Fontana then began a series of sculptures known as the Nature, primordial balls of clay incised with slashes or holes, in which he once again harnessed the full potential of tangible artistic matter in order to express the existential angst that accompanied space travel. It was not however, until the conception of La Fine di Dio in 1963 that Fontana succeeded in placing matter and concept into a perfect, transcendental equilibrium, while at the same time, conveying man’s own experience in space.

Exhibition view of Fondazione Prada Ca’ Corner della Regina, 2011. Courtesy Fondazione Prada. Photo: Attilio Maranzano. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2018.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale, La Fine di Dio, 1963. Fondazione Prada, Milan. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2018

EVOLUTION: By April of 1963, Fontana had, as he wrote to his friend Jef Verheyen, fnished his ‘series of “oval” paintings with the title The End of God, to show them in Zurich…’ (Fontana to J. Verheyen, 5 April 1963, in E. Crispolti, ed., op. cit., p. 30). The first of these were shown among examples of Fontana’s earlier work at the Gimpel Hanover Galerie, Zurich at the end of May. A month later, an exhibition dedicated solely to this new body of work was held at Beatrice Monti della Corte’s Galleria dell’Ariete in Milan.

With the exhibition titled ‘Lucio Fontana: Le Ova (The Eggs)’, from the very beginning of their creation, La Fine di Dio became equated to the form of the egg, one of the single most universal symbols of life itself. An iconic symbol in the iconographical lexicon of the world’s greatest ancient civilizations, the primordial and cosmic eggs occupy central roles in the cosmogony of the Ancient Egyptians, Chinese, the Greek Orphic tradition, Hinduism. In addition, this form holds a deeply symbolic meaning in both Judaism and Christianity, serving as a symbol of the Resurrection. A form without end that represents the eternal cycle of birth, life and death and rebirth, an embryo of new form and potential, as well as the embodiment of both the organic worlds of nature, life and matter and that of the more mystical and unknown realms of space, infinity and the spirit.

While many have disputed whether the metaphorical allusions were purposefully intended by the artist in this series, Fontana was fascinated by the symbolism of the oval in the cosmological theories of the birth and formation of the universe and there is no doubt he would have been well-aware of the powerful, universal meaning of the form that he had chosen, as well as by its formal characteristics. It has been stated that Fontana made his first oval in Adolfo Wildt’s class at the Brera Academy, Milan, in which he made his students sculpt a perfect egg in marble (P. Gottschaller, op. cit., p. 109). And, he was also well-aware of Brancusi’s perfectly formed, flawless work, Le nouveau né, describing the sculptor’s “egg” as ‘truly something colossal’ (Fontana, quoted in E. Crispolti & R. Siligato, eds., Lucio Fontana, exh. cat., Rome, 1998, p. 251). In purely formal, artistic terms, the form of the ovoid was of great importance to Fontana. Denoting wholeness and totality, it is a metaphysical symbol of perfection, complete and without end, and as such, simultaneously serves to be exactly the opposite: an aesthetic non-form. It was paradoxically through using this form – the signifier of everything and thus simultaneously of nothing – that Fontana arrived at his ultimate artistic goal with La Fine di Dio: to ‘represent nothingness’. In this formal context therefore, La Fine di Dio serve as the final, triumphant union of Fontana’s exploration into matter, a series in which material, the gesture, space, time come together in holistic union, which also took the shape of an oval, the shape of the universe and therefore all of life, existence, death and nothingness itself.

When, in February 1964, Fontana exhibited a selection from the now enlarged group of Fine di Dio, he ensured a change in their title, now presenting them as ‘Les Oeufs céleste’ (‘The Astral Eggs’). Like man evolving from his inhabitation of earth into space, so the works in this exhibition had a far stronger sense of cosmic mystery than their earlier predecessors. Moving away from the elemental colours and primeval gestures of the early works, these later Fine di Dio are marked by an increase in buchi, their surfaces almost covered with smaller, more refned, constellation-like marks. Just as the cosmos had been revealed to be an ever-expanding, unquantifable concept, so Fontana appeared to echo this in these astral eggs, adding to their surfaces and thereby intensifying the sense of the transmutation of matter into spirit, body into soul. So enamoured of these later, more astral Fine di Dio was Fontana, that he even returned to several of the earlier works, adding further punctures to them and in some cases even resurfacing them with golden brown pigment and glitter, to further the stellar efect of their surfaces.

It is to this group that the present Concetto spaziale, La fne di Dio belongs. Featuring in an important group of photographs of 1963, which show Fontana admiring the present work and two others in the basement of his Milan studio, this work appears in the images in its initial state, before the artist added the sparkling lustrini that now defines its richly coloured, cosmic surface. Unlike others that are grouped within the ‘Les Oeufs céleste’ however, the present work is not so heavily strewn with buchi that it loses its innate structure. Indeed, it serves as a bridge between these two groups; a work in which the muted pink carnal pigment is vitalised with the radiance of Fontana’s lustrini, encapsulating man’s move from earth to space.

Lucio Fontana, Galerie Iris Clert, Paris, 1964. Photo: Shunk-Kender © J.Paul Getty Trust. The Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles, (2014.R.20). Gift of the Roy Lichtenstein Foundation in memory of Harry Shunk and Janos Kender. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2018

DEATH AND TRANSCENDENCE: It was not until March 1964, the month following Iris Clert’s Paris exhibition, that La Fine di Dio were finally exhibited with this title, the phrase that Fontana had used in private since the moment of their conception on paper as early as 1960. By turning to this powerful statement, Fontana was not only rejecting the purely formalist approach that critics had been taking in regards to these works, but according to Enrico Crispolti, it was with this provocative title that the artist could truly invoke the meaning and conceptual intent of this iconic series.

Just as he believed that art would become extinct and irrelevant in this new world of cosmic adventure, so too, a belief in God was for Fontana an idea that would have no place in this new conception of the universe. In the face of the vastness of the universe, he believed that all earthbound thought, beliefs, traditions and practices, including the idea of a Christian God, would become redundant. This concept, as well as the title he chose, echoes Friedrich Nietzsche’s famous statement of 1882, ‘God is dead’, a refection on the supremacy of the part of Enlightenment thought that rejected religion in favour of rationalism and science. Just under a century later, Fontana was imparting this same idea: hailing the end of a society that placed its beliefs in an earthly conception of a deity and instead calling for a new faith in the infinite.

As he explained to Carla Lonzi: ‘God is nothing… I do not believe in gods on earth, it is inadmissible, there can be prophets, but not gods, God is invisible, God is inconceivable, therefore, today an artist cannot represent God on a chair with the world in his palm and a beard… It is in this, that religions must adapt themselves to the discoveries of science. The Pope too is outdated in his conception of modern discoveries, because the universe proves that it is in itself infinite, and that the infinite is nothingness and that eternity does not exist on earth... Eternity, faced by nothingness, by time…does not exist, because now and forty or fifty thousand years in the future, neither the doors of the Gates of Saint Peter, nor the Pope will exist. This is what man must stop believing – man must forget his ambition to immortalise his being in material forms made of marble and bronze…’ (Fontana, quoted in C. Lonzi, ‘Milan, 10 October 1967: Carla Lonzi interviews Lucio Fontana,’, edited by P. Campiglio, reproduced in Lucio Fontana: Sedici sculture/ Sixteen sculptures, 1937-1967, exh. cat, Milan & London, 2007, pp. 31-32).

Instead, Fontana offered a new form of faith in the infinite; in Crispolti’s words: ‘God turns into the absolute infinity of space’ (E. Crispolti,op. cit., p. 73). It was with the holes carved into the canvas, gestures that affirmed a mystic belief in the future, that Fontana succeeded in invoking the same eternal, intangible and mysterious presence of a higher form for the believers of the future.

Yet, Fontana also realised that the new era of spatial consciousness, carried, like birth itself, the inevitability of death. Just as all earthbound objects, ideas and art would be one day rendered extinct within the infinite dimension of space, so too would man expire. It was therefore with Concetto spaziale, La fine di Dio and this series, which were designed to be the very last material works of art made by man, that Fontana succeeded in creating truly spatial objects in every sense. Appearing like a wondrous astral artefact, this work embodies a transcendent transformation of matter into spirit, opening the gates of man’s mind to conceive of a future, previously unimagined world. At the same time it is a portentous object that signifies art and man’s eventual demise and therefore, their ultimate liberation. ‘When man realises that he is nothing, nothingness itself, that he is pure spirit, he will no longer have materialistic ambitions…[he] will become like God, he will become spirit. This is the end of the world and the liberation of matter, of man’ (Fontana, quoted in E. Crispolti, op. cit., p. 81).

Another highlight is Salvatore Scarpitta’s High Bride of 1960, a rare large-scale monochrome relief painting from a pivotal period in the artist’s oeuvre (estimate: £1,000,000 - 1,500,000). It belongs to a series of radical and trailblazing wrapped canvas works dubbed ‘extramurals’ that challenged and significantly expanded the concept of painting in the post-war era. First conceived of in 1957 and an influence on the reductive art of Scarpitta’s Italian peers Lucio Fontana and Piero Manzoni, the extramurals turned the tools and materials of art-making into the artwork itself.

Lot 114. Salvatore Scarpitta (1919-2007), High Bride, signed, titled and dated 'SALVATORE SCARPITTA 1960 "HIGH BRIDE"' (on the reverse), bandages and mixed media on canvas, 60 x 401/8in. (152.5 x 102cm.) Executed in 1960. Estimate GBP 1,000,000 - GBP 1,500,000 (USD 1,307,000 - USD 1,960,500). © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

Mariolina Bassetti, Chairman Italy, Head of Continental Europe, Post-War & Contemporary Art: “We are pleased to offer the second edition of ‘Thinking Italian’, the only auction dedicated to Italian works of art happening during Frieze week in London this season. The new brand will be reiterated across the auction calendar throughout international sales of Post-War and Contemporary Art happening in worldwide locations, from America to Asia. The dialogue and understanding of Post-War and Italian Art grows year on year, and as 2018 marks Christie’s 60th anniversary in Italy, we are excited to celebrate Italian art and culture across categories, as we will also be offering masterpieces of Italian Design in our upcoming sale Thinking Italian: Design, taking place on London on 17 October.”

Christie’s continues to hold the world record price for a work by Lucio Fontana at auction and will present a fresh selection of some of the artist’s most influential artistic creations, including two buchi, which illustrate the first artistic manifestation of Fontana’s movement, Spatialism, conceived in 1947. The present lots are early examples of Fontana’s ground-breaking buchi, showcasing the artist’s greatest practice: the act of puncturing through the surface of the canvas to create an irrevocable hole that reveals a chasm of immaterial darkness. As if gazing down at earth from space and seeing the sparkling networks of light radiating amidst the deep black of the cosmos, Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale of 1952 and 1953 present poetic constellations of holes scattered across the gleaming white surface of the canvas. Just under a decade later, Fontana extended the potential of this ground-breaking gesture by elongating his buchi so that they became long, elegant vertical slashes, or tagli. One of the most elegant iterations of Fontana’s tagli was executed in 1964, a moment when the artist was at the height of his powers. Fontana tore seven slashes through the previously sacrosanct surface, integrating a new spatial dimension into the picture plane and in so doing, significantly redefined the boundaries of painting. Discerning collectors may also appreciate the verso of this work, which is endowed with a specific autobiographical memory, as Fontana added the line, ‘Today I am having breakfast with the painter Clee’, a reference to the artist Clelia Cortemiglia, an artist who was a close friend and also student of the artist.

Lot 125. Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), Concetto spaziale, Attesa, signed, titled and inscribed 'l. fontana “Concetto Spaziale” ATTESA Perché il mondo marcia male? perché gli manca l'altro coglione al fanco !!' (on the reverse), waterpaint on canvas, 29 1/8 x 23 7/8in. (74 x 60.5cm.) Executed in 1965-1966. Estimate GBP 2,500,000 - GBP 3,500,000(USD 3,267,500 - USD 4,574,500). © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

Provenance: Renato Guttuso Collection, Rome (acquired directly from the artist).

Anon. sale, Christie's London, 20 October 2008, lot 117.

Acquired from the above by the present owner.

Literature: E. Crispolti, Fontana, Milan 1999, no. 247 (illustrated in colour, p. 231).

Enciclopedia dell'Arte, Le Garzantine-Arte, Milan 2002 (illustrated in colour, p. 1507).

A. Vettese, Lucio Fontana. I tagli, Cinisello Balsamo 2003 (illustrated on the cover; illustrated in colour, p. 42 ).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana; Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, vol. II, Milan 2006, no. 65-66 T 35 (illustrated, p. 823).

Exhibited: Milan, PAC Padiglione d'Arte Contemporanea, Centenario di Lucio Fontana. Cinque mostre a Milano: Lucio Fontana. Idee e capolavori, 1999 (illustrated in colour, p. 61).

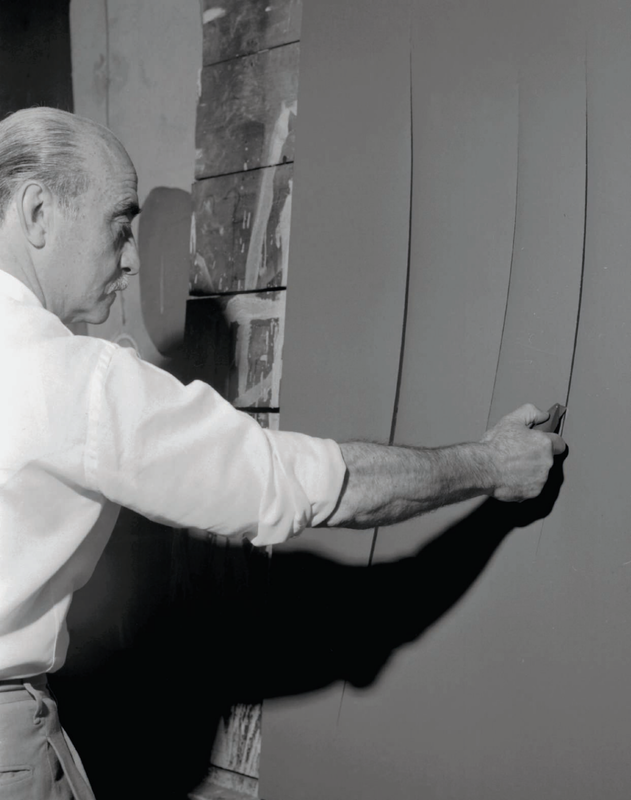

Lucio Fontana. Photo Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved

Note: A single slash incises the faming red monochrome canvas of Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale, Attesa, its irrevocable, graceful passage at once a destructive act enacted against the sacrosanct pictorial plane, while at the same time a gesture that is wholly emancipatory, liberating painting from the stultifying traditions of the past and offering an entirely now conception of what art could be. Executed in 1965-1966, this dramatic work is one of the artist’s famed tagli or ‘cuts’, a series that Fontana had inaugurated over a decade previously, in 1958. The present work is set apart from this series due to its unique provenance: it was presented as a gift from Fontana to fellow Italian post-war artist Renato Guttuso, this act providing a revealing and enlightening insight into the world of 20th Century Italian art.

The relationship between Guttuso, a realist painter actively involved in the Italian Communist Party from the Second World War, and Fontana, an artist who decisively called for the end of representational painting, wholeheartedly embracing the pioneering possibilities offered by the Space Age and the future, is intriguing. How could Guttuso, who prepared his canvases using his knowledge of ancient art and traditional skills within the greater figurative tradition, be linked with Fontana, who attacked the canvas with slashes, holes and insertions? Yet, their worlds’ were in fact not so disparate. In Milan in the 1930s, a city that buzzed with the talent and innovations of generations of artists, the two artists not only associated within the same circles, but also exhibited in the same gallery, Il Milione, which drew the attention of the most important art critics of the time. Fontana, who had just come back from Argentina in 1930, had his first show at the Galleria Il Milione shortly followed by a second one in 1935; this is considered to have been the first exhibition of abstract sculpture in Italy.

The effectiveness of the exhibition strategy that the Galleria Il Milione developed, meant success for Guttuso’s shows; he therefore became an important figure in the Milanese art scene, coming to know a number of his contemporaries. During the turbulent years of economic woe of the early 1930s, Guttuso was completing his military service in Milan as an army officer, and had the opportunity to help his friends, among them Fontana, by inviting them to have lunch in the canteen of the barracks. Fontana reciprocated this kindness when Guttuso, having spent a short period of time in Palermo, decided to go back to Milan: Fontana managed to find his friend a studio in Guglielmo Street, very close to his own. The two friends used to have lunch together in Fontana’s studio, enjoying the pasta cooked by Teresita, Fontana’s wife. Some evenings, they headed to the Galleria Il Milione, while sometimes they went to the Cafè Bifi, which was frequented by many of the intellectuals living in Milan during that period, such as Quasimodo, Mucchi, Cantatore, Tomea and Carrieri. Both Guttuso and Fontana formed part of the Corrente movement which came intoexistence in 1938, with the magazine Corrente di Vita Giovanile as its focus – it would later shorten its name to Corrente and focus on the painters, sculptors, poets and critics of the time.

The friendship between these two important Italian artists lasted for the years that followed, in particular when Guttuso begun to spend the summer in Velate at the end of the 1950s. This was near Varese, where Fontana moved in his final years, and so the two artists once more began to spend time together. It was during this phase of their lives that the idea of the gift of Concetto spaziale, Attesa originated: the large red work with its bold, calligraphic slash is a tribute to a friendship that bridged any differences of style or opinion, lasting over thirty years.

Since his days in Argentina during the Second World War, and upon his return to Milan in 1947, Fontana had pursued an artistic vision that united the rapidly-developing, pioneering world of science with contemporary art making. He called for an art form that would embrace the dynamic, intangible properties of light, space and time, so to better reflect and embody the spirit of the times. Soon after Fontana had inaugurated Spatialism, he made his most important gesture: the hole, and just under a decade later, he achieved, with a clean and minimal conceptualism, his career-long desires in the form of the tagli. Tearing through the surface of the canvas itself, these punctures, supremely elegant and breathtakingly simple, served to incorporate three-dimensional space into the constitution of the work itself, turning it from a static, inert two-dimensional plane, into a multi-dimensional object. In addition, the sliver of intriguing, enigmatic darkness that this incision revealed, served as the embodiment of the endless, infinite cosmos that had been only recently revealed to man. With a work such as Concetto spaziale, Attesa the slash creates a deliberate visual contrast between the material – the red canvas – and the immaterial, the slim chasm of the cosmos that Fontana has captured in our realm. Fontana is deliberately playing with scale, introducing a shard of infinity that is designed to prompt us into a contemplation of the infinite scale to which now, breaking away from earth’s gravity and into the vastness of space, man was now exposed. ‘Now in space, there is no longer any measurement’, he explained.

‘Now you see infinity... in the Milky Way, now there are billions and billions... The sense of measurement and of time no longer exists. Before, it could be like that... But today it is certain, because man speaks of billions of years to reach... and so, here is the void, man is reduced to nothing... When man realises... that he is nothing, nothing, that he is pure spirit he will no longer have materialistic ambitions... man will become like God, he will become spirit. This is the end of the world and the liberation of matter, of man... man will become a simple being like a flower, a plant and will only live through his intelligence, through the beauty of nature and he will purify himself of blood, because he constantly lives with blood... And my art too is all based on this purity, on this philosophy of nothing, which is not a destructive nothing, but a creative nothing, do you understand? And the slash, and the holes, the first holes, were not the destruction of painting... it was a dimension beyond the painting, the freedom to conceive art through any means, through any form. Art is not painting and sculpture alone: art is a creation of man, who can transform it into anything... as it may also end, because such exceptional events will happen... Art will seem to be too elementary: it will be superseded by man’s intelligence and other activities will replace art’ (Fontana, quoted in E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana: Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, Tomo I, Milan, 2006, p. 81).

The elegant, single cut that slices through the canvas of Concetto spaziale, Attesa therefore represents both a conceptual and visual encapsulation of Fontana’s search for a new artistic language. All superfluous elements are eliminated, leaving only the artistic gesture, which resonates with a powerful serenity and stillness. In Concetto spaziale, Attesa, Fontana was deliberately exploring a means of approaching an art of pure spirit, echoing the almost spiritual transformation that he perceived as the next level of man’s evolution and awareness, within the traditional bounds of the picture plane. Fontana’s cut in this canvas illustrates the obsolete nature of traditional art forms as mankind approaches a new age of science, reason and awareness of the immensity of space; at the same time, he has managed to create an unsullied zone of pure conceptualism, of pure spirit, and it is in this void that we can glimpse fleetingly the limitless wonder of the heavens and gain some awareness of our microscopic part within the giant turning wheel of the galaxy. As he explained, ‘And the slash, and the holes, the first holes, were not the destruction of the painting…it was a dimension beyond the painting, the freedom to conceive art through any means, through any form. Art is not painting and sculpture alone: art is a creation of man, who can transform it into anything…as is may also end, because such exceptional events will happen…Art will seem to be too elementary: it will be superseded by man’s intelligence and other activities will replace art’ (Fontana, quoted in ibid., p. 81) Indeed, it is the slash in the canvas that is sole protagonist of this work. Just as Fontana’s contemporary and friend, Yves Klein had declared that his paintings were the ashes of his art, so too the paint and canvas in Fontana’s Attese are almost incidental. It is the space that is irreducible, undeniable, inerasable. While over millennia to come, the material will be destroyed or expire, the simple gesture of the cut, and the space marked out by Fontana will remain, intangible and thus infinite. ‘Art is eternal, but it cannot be immortal,’ Fontana in the First Spatial Manifesto had two decades earlier declared. ‘We plan to separate art from matter, to separate the sense of the eternal from the concern with the immortal. And it doesn’t matter to us if a gesture, once accomplished, lives for a second or a millennium, for we are convinced that, having accomplished it, it is eternal’ (signed by Fontana, G. Kaisserlian, B. Joppolo, M. Milani, reproduced in E. Crispolti & R. Siligato, ed., Lucio Fontana, exh.cat., 1998, pp. 117-18).

Like an exquisitely refined wound bleeding into a crimson background, Concetto spaziale, Attesa embodies both the death and the resurrection of the canvas. Fontana’s desecration of the canvas is particularly subversive considering his roots in Italy, the land of the Renaissance. Indeed, his vocabulary of slashes is not without its pedigreed history – the greatest works of Renaissance and Baroque art enter his oeuvre. Particularly resonant is the lance wound of Christ, memorialized in paintings of the crucifxion, the pietá and the resurrection; indeed, the verticality and frontality of his slashes suggest the form of a figure on the cross, while the pain evoked in the wounding of the canvas invokes Christ’s suffering. Indeed, the motif of the crucifxion is entirely apt for Fontana’s staging of death and rebirth in the medium of painting. ‘My art is directed towards [a] purity’, Fontana stated at the end of his life, in 1967, ‘it is based on the philosophy of nothingness, a nothingness that does not imply destruction, but a nothingness of creation…’ (Fontana, quoted in P. Campiglio, ed., ‘Milan, 10 October 1967: Carla Lonzi interviews Lucio Fontana’ in Lucio Fontana Sedici sculture, Sixteen sculptures 1937-1967, exh. cat., London, 2007, p. 35).

Lot 124. Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), Concetto spaziale, Attese, signed, titled and inscribed 'l. fontana "Concetto Spaziale" ATTESE Margherita! ti scrivo per dirti che ho saputo che me hai tradito…' (on the reverse), waterpaint on canvas, 28 7/8 x 23 5/8in. (73.5 x 60cm.) Executed in 1965. Estimate GBP 2,000,000 - GBP 3,000,000 (USD 2,614,000 - USD 3,921,000). © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

Provenance: Private Collection, Milan.

Waddington Custot Gallery, London.

Acquired from the above by the present owner in 2002.

Literature: E. Crispolti, Fontana. Catalogo generale, Milan 1986, vol. II, no. 65 T 137 (illustrated, p. 584).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, Milan 2006, vol. II, no. 65 T 137 (illustrated with wrong image, p. 769).

Lucio Fontana in his studio, Milan, 1962. Photo: Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2018.

Note: A surface of pure, unblemished and seemingly unending monochrome white is penetrated in the centre by a troupe of four balletic slashes in Lucio Fontana’s serene and supremely elegant Concetto spaziale, Attese of 1965. At this time, the colour, or indeed the ‘non-colour’, white had become one of the most dominant aspects of Fontana’s prolifc oeuvre, its importance evidenced the following year, at the 1966 Venice Biennale, when the artist exhibited twenty white tagli. Together, the combination of the vertical cuts slicing singularly and irrevocably through the monochrome white canvas presented the perfect and most complete embodiment of Fontana’s Spatialism, the movement he founded in 1947, not only turning the canvas into a three-dimensional object, but transforming it into an enigmatic portal of discovery and potential, providing a glimpse into the unknown, and the fourth dimension. Revelatory in its concept and infinitely poetic in its appearance, Concetto spaziale, Attese immortalises the fleeting moment of the gesture for eternity; a crystallisation of the artist’s career-long formal and conceptual concerns.

It was with a piece of paper that Fontana first realised the artistic potential of piercing through the physical surface of the artwork itself. In 1949, Fontana created a number of holes in a piece of card, inaugurating his series of buchi. Realising the power of this gesture, Fontana moved to canvas, puncturing this previously inviolable, fat surface, which had served as the site of pictorial creation for centuries, and thereby opening this sacred plane up to integrate the dynamic concepts of real time and space into the artwork itself. The black chasms of seemingly unending space that these holes revealed also served for Fontana as invocations of the cosmos, revealing to the viewer a small yet powerful vision of dark, boundless celestial space. Fontana later explained, ‘my creation of holes was a radical gesture that shattered the space of the painting and declared: after this, we are free to do as we like. We cannot close the space of the picture within the limits of the canvas, for it must be extended out to all the space around it’ (Fontana, quoted in D. Palazzoli,‘Intervista con Lucio Fontana’, bt, no. 5, October-November 1967, in Lucio Fontana, exh. cat., London, 2015, p. 212).

Fontana’s diagram for the Technical Manifesto of Spatialism, 1951. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2018

Spiral galaxy. Photo: Fox Photos/Hulton Archive/Getty Images.

It was then, just under a decade later, that Fontana extended the potential of this groundbreaking gesture by elongating his buchi so that they became long, elegant vertical slashes. Over the previous years, Fontana had experimented ceaselessly with a variety of materials and ideas in his quest to create a work that would serve as the embodiment of his Spatialist ideas. Working with an abundance of materials in series such as the pietre or barocchi, in 1958, Fontana banished ornamentation, embellishment and decoration and instead focused solely on the gesture itself, beginning the series for which he would become best known: the tagli. Unlike the gesturality and physicality of the buchi, the dramatic, singular gesture of the tagli resonated with an elegant minimalism, serving as the embodiment of the artist’s formal and theoretical concerns. ‘With the taglio’, Fontana stated, ‘I have invented a formula that I think I cannot perfect…I succeeded in giving those looking at my work a sense of spatial calm, a cosmic rigor, of serenity with regard to the Infnite. Further than this I could not go’ (Fontana, quoted in P. Gottschaller, Lucio Fontana: The Artist’s Materials, Los Angeles, 2012, p. 58).

While the four slashes, which dance like calligraphic marks across a sheet of white paper, appear randomly deployed amidst the monochrome canvas in Concetto spaziale, Attese, they were in fact the result of a lengthy period of intense and deep contemplation by Fontana. After he prepared the canvas, applying white monochrome waterpaint with a brush, carefully ensuring that the surface remained perfectly smooth, free of any brushstrokes or evidence of the artist’s own hand, he then, with methodical care and precision, slashed through the canvas from top to bottom with a knife. The subtly varying lengths, angles and positions of each of the slashes in Concetto spaziale, Attese, and their rhythmic arrangement across the width of the canvas demonstrates Fontana’s scrupulous attention to detail and his extreme dedication to refning the minute details of his technique. Describing his artistic process, Fontana stated, ‘I need a lot of concentration. That means I don’t just walk into my studio take of my jacket, and boom, I make three or four tagli. No, sometimes I leave the canvas there propped up for weeks before I am sure what I will do with it, and only when I feel certain do I begin, and it is rare that I waste a canvas; I really need to feel in shape for doing these things’ (Fontana, quoted in P. Gottschaller, ibid., p. 82). With this description of his practice, Fontana dispelled any notion that his cuts were spontaneous, unplanned actions, carried out without planning or thought. Indeed, Fontana recalled an occasion when a visitor to his studio suggested he too could create tagli, remembering, ‘A while ago a surgeon came to visit me in my studio, and he told me that he was also very capable of making “these holes”. I responded to him that I too can cut of a leg, but I also know the patient will die of it. If he cuts it, however, it’s a different situation. Fundamentally different’ (Fontana, quoted in P. Gottschaller, ibid., p. 89).

Regarded as the result of this meticulous, near meditative practice, the cut becomes more than simply a physical action enacted arbitrarily or automatically upon the canvas, but a methodical, transcendent gesture flled with meaning and potential. It is in this way that Fontana realised his desire to transform the artwork from a material object into a spatial concept, the feeting action of the cut forever immortalised and thus eternal. ‘My cuts are above all a philosophical statement, an act of faith in the infnite, an afirmation of spirituality’, Fontana declared in 1962. ‘When I sit down to contemplate one of my cuts, I sense all at once an enlargement of the spirit, I feel like a man freed from the shackles of matter, a man at one with the immensity of the present and of the future’ (Fontana, quoted in L. Massimo Barbero, Lucio Fontana: Venice/New York, exh. cat., Venice & New York, 2006-2007, p. 23).

For Fontana, the tagli came to serve as the purest distillation of his Spatialist program, a perfect and complete visual incarnation of his artistic aims. Since the early 1940s when he had been living and working in Buenos Aires, Fontana desired an art form that would better reflect the new age of scientific and technological discovery. At the dawn of a new technological age, where particle physics and space exploration had completely redefined man’s understanding of the world and his place within it, Fontana realised that traditional forms of artistic representation had little use and no meaning. Instead, Fontana understood that the artist, like the scientist, had to compete with a vision of the world exclusively comprised of time, matter, energy and above all, the pervasive void of deep space. Faced with this reality, Fontana called for artists to embrace this revolutionary, exciting age and produce a new art entrenched in the extraordinary developments of science and space travel. Writing in the Manifesto Blanco of 1946 – the frst of a series of Spatialist manifestos that Fontana would publish – the artist declared: ‘We live in the mechanical age. Painted canvas and upright plaster no longer have any reason to exist… Colour, the element of space, sound, the element of time and movement which takes place in time and in space, are the fundamental forms of the new art, which contains the four dimensions of existence, time and space’ (Manifesto Blanco, 1946 in E. Crispolti and R. Siligato, eds., Lucio Fontana, exh. cat., Rome, 1998, p. 115).

It was with the monochrome white surface of the canvas enabled him to attain the sense of limitless, infnite, cosmic space that he wanted to convey through his tagli. Having experimented with a range of monochrome colours, it was white which most encapsulated the sense of boundless, unfathomable space that Fontana sought to convey in his work. White, he said, is the ‘purest colour, the least complicated, the easiest to understand’, that which most immediately and most successful attained a ‘pure simplicity’ and the ‘pure philosophy’ which he sought to attain in the works of the last years of his life (Fontana, quoted in E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, Tomo I, Milan, 2006, p. 79). While his artistic contemporaries, Piero Manzoni and Enrico Castellani were exploring the potential of white or indeed colourless canvases, seeking to return art to a blank virginal state, a tabula rasa, for Fontana, the monochrome canvas was not simply an empty receptacle, but was endowed, he believed, with a transcendent, transformative potential, invoking an infinite dimension.

The year after Fontana executed Concetto spaziale, Attese, he continued to explore the visual potential of white in a critically acclaimed installation at the XXXIII Venice Biennale, for which he was awarded the Grand Prize of Painting. Created in collaboration with the architect Carlo Scarpa, Fontana’s Ambiente Spaziale (Spatial Environment) consisted of a luminous white labyrinthine room filled with twenty white tagli, each with a single white slash. Fontana explained the impetus behind his design: ‘I wanted to create a ‘spatial environment’, by which I mean an environmental structure, a preliminary journey in which the twenty slits would be as if in a labyrinth containing blanks of the same shape and colour’ (Fontana, quoted in S. Whitfeld, Lucio Fontana, exh. cat., London, 1999, p. 200). In 1968, he created a similar maze-like room for the ‘Documenta 4’ in Kassel, Germany, placing a single, large, revelatory slash in a totally white room.

Lot 129. Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), Concetto spaziale, Attese, signed, titled and inscribed ‘l. fontana concetto spaziale ATTESE oggi vado a colazione colla pittrice Clee’ (on the reverse), waterpaint on canvas, 23 5/8 x 28 ¾in. (60 x 73cm.) Executed in 1964. Estimate GBP 1,800,000 - GBP 2,500,000(USD 2,352,600 - USD 3,267,500). © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

Provenance: Galleria Notizie, Turin.

Galleria Sperone, Turin.

Private Collection, Veduggio.

Acquired from the above by the present owner.

Literature: E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogue raisonné des peintures, sculptures et environnements spatiaux, Bruxelles 1974, vol. II,no. 64 T 47 (illustrated, p. 155).

E. Crispolti, Fontana. Catalogo generale, Milan 1986, vol. II, no. 64 T 47 (illustrated, p. 523).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, Milan 2006, vol. II, no. 64 T 47 (illustrated, p. 714).

Lucio Fontana performs a cutting, Milan, 1960. Photo: © Giancolombo. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2018.

Note: Seven slashes rhythmically rupture the pristine surface of Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale, Attese, revealing delicate slivers of the darkness that lies beyond the picture’s edge. One of the most elegant iterations of Fontana’s best-known series, the tagli, this work was executed in 1964, a moment when the artist was at the height of his powers. While simultaneously creating his iconic Fine di Dio works, large, otherworldly oval canvases rent open with myriad sizes holes, Fontana continued to explore the powerful aesthetic and symbolic potential of his sleek, single slashes; the works which have come to define his movement: Spatialism. With the slash, an act at once destructive and revelatory, iconoclastic and iconic, Fontana tore through the previously sacrosanct surface, integrating a new spatial dimension into the picture plane and in so doing, significantly redefined the boundaries of painting.

Concetto spaziale, Attese is inextricably linked to the post-war society in which it was created. Unlike his artistic counterpart Alberto Burri, Fontana chose to turn away from the destruction, both physical and psychological, that the Second World War had wrought upon mankind, and instead focus wholeheartedly upon the future, embracing all the possibility and excitement that the unknown held. Living and working in Italy in the years immediately following the war – Fontana had returned to Milan to find his pre-war studio bombed to the ground, while Burri returned having served as a medic in the Italian army before enduring incarceration in Texas – both artists were impelled to find a new artistic language that would befit this post-war era. While they both believed that traditional modes of painting and sculpture had no place in the post-war era, they found radically different modes of expression with which to better reflec the paradoxical sentiments of these times.

As Fontana declared, ‘Man today is too bewildered by the vastness of his world, he is too overwhelmed by the triumph of Science, he is too dismayed by the new inventions which follow one after the other, to be able to find himself in figurative painting. What is needed is an absolutely new language, a ‘Gesture’ purifed of all ties with the past, which gives expression to this state of despair, of existential anguish’ (Fontana, quoted in L. Massimo Barbero, Lucio Fontana: Venice/New York, exh. cat., Venice & New York, 2006-2007, p. 23).

With a rapt fascination for science and technology, Fontana looked resolutely skywards, watching with ever increasing awe as the earth’s atmosphere was breached, first with satellites, before man himself conquered space. He was determined, as the Futurists had been before him, that art should reflect these pioneering new times, quickly recognising that painting and sculpture were unable to aptly convey the new concepts of space and time that had been discovered. In the face of explosive technological and scientific innovation and change, what use, he asked, did illusionistic painted representations on canvas have? ‘Think about when there are big space stations’, he asked. ‘Do you think that the men of the future will build columns with capitals there? Or that they will call painters to paint?... No, art, as it is thought of today, will end’ (Fontana, quoted in A. White, ‘Art Beyond the Globe: Lucio Fontana’s Spatial Identity’ emaj, no. 3, 2008, p. 2).

The ceiling of Museo dell’Automobile di Torino, Turin. Photo: ©Iro Nikolaou, 2018.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto Spaziale. Venice Moon, 1961. Private Collection. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2018.

Contemporary art, Fontana believed, needed to come out of its frame and of its pedestal to instead incorporate and therefore exist in real time, space and movement. It was upon his return to Milan in 1947 following a seven-year sojourn in Buenos Aires that these ideas took shape. While in Argentina, he had already published a manifesto, the Manifesto Blanco, in which, borrowing the rhetoric of his Futurist forebears, Fontana denounced traditional forms of painting and sculpture, instead calling for an art that embodied the spirit of the intrepid, rapidly changing times. ‘We need a change in essence and in form’, the manifesto declared. ‘We need to go beyond painting, sculpture, poetry, and music. We need a greater art in harmony with the requirements of the new spirit’ (Manifesto Blanco, 1946 in E. Crispolti & R. Siligato, eds., Lucio Fontana, exh. cat., Rome, 1998, p. 115). A year later, Fontana presented a second tract entitled Primo Manifesto spaziale, which presented the central tenets of Fontana’s newly founded Spatialism, the movement to which he would remain devoted for the rest of his career. ‘We refuse to believe that science and art are two distinct facts, that the gestures accomplished by one of the two activities cannot also belong to the other’, Fontana declared in this text, surmising the central aspects of the movement. ‘Artists anticipate scientific gestures, scientific gestures always provoke artistic gestures’ (Primo Manifesto spaziale, 1947, in ibid., p. 118).

Along with the space race, Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity had hit Fontana with the force of a revelation. Discovering these pioneering concepts, Fontana sought in his art to look beyond the bounds of reality and representation: just as Einstein expounded the existence of the fourth dimension, so Fontana sought to capture this concept in artistic form. ‘Spatial is what is beyond the perspective...the discovery of the cosmos...Which are all ideals aren’t they? Foreground, middle ground and perspective, which is the third dimension and which is also parallel to the discovery of science.... Einstein’s discovery of the cosmos is the infinite dimension, without end. And here we have the foreground, middle ground and background, what do I have to do to go further? I make a hole, infinity passes through it, light passes through it, there is no need to paint...everyone thought I wanted to destroy; but it is not true, I have constructed’ (Fontana in conversation with Carla Lonzi, 1967, in C. Lonzi, Autoritratto, Bari, 1969 p. 176).

It was through the cut that Fontana succeeded, with a single, simple and irrevocable gesture, to encapsulate these concepts in his art. When, in 1958, he first sliced through the canvas, he discovered that he could not only transform the previously inviolable pictorial surface into a three-dimensional object that interacted and coexisted with the space surrounding it, but, by revealing the black, empty and seemingly endless space beyond the surface of the canvas, he could offer the viewer a glimpse of the infinite: a view of the fourth dimension. ‘When I hit the canvas I sensed that I had made an important gesture’, he explained. ‘It was, in fact, not an incidental hole, it was a conscious hole: by making a hole in the picture I found a new dimension in the void. By making holes in the picture I invented the fourth dimension’ (Fontana, quoted in P. Gottschaller, Lucio Fontana: The Artist’s Materials, Los Angeles, 2012, p. 21). Just as scientists and astronauts were altering the limits of human consciousness with their scientific discoveries and technological inventions, so Fontana pioneered a new form of art that offered a new way of seeing and thinking about the world.

While the tagli are distinctly of their time, conceived as the embodiment of the epoch in which they were created, with the slash Fontana believed he had invented a gesture that would transcend the boundaries of earthly time. The cut was an eternal gesture that, unlike the material itself, which would inevitably decay over years, existed without end. ‘We plan to separate art from matter’, he had declared in the Primo Manifesto spaziale of 1947, ‘to separate the sense of the eternal from the concern with the immortal. And it doesn’t matter to us if a gesture, once accomplished, lives for a moment or a millennium, for we are convinced that, having accomplished it, it is eternal’ (Primo Manifesto spaziale, 1947, op. cit., p. 118). It was with works such as Concetto spaziale, Attese that Fontana achieved an absolute clarity, the highly concentrated act of slicing the canvas serving as the climax of his artistic explorations. As he stated, ‘With the taglio I have invented a formula that I think I cannot perfect… I succeeded in giving those looking at my work a sense of spatial calm, of cosmic rigour, of serenity with regard to the Infinite. Further than this I could not go’ (Fontana, quoted in P. Gottschaller, op. cit., p. 58).

The inherently emancipatory nature of the slashes is also reflected in the sense of anticipatory optimism evoked by the titles of the tagli themselves. Every Attesa or ‘expectation’, a word affixed to the title of Fontana’s slash paintings, evokes not just the immeasurable space beyond the surface of the earth, but also the vastness of the human mind. Opening up the boundaries previously instilled by the confines of the canvas, Fontana was likewise seeking to expand the confines of human consciousness, leading the viewer into a new realm of heightened spiritual awareness. Embodying the mystery of an unknown future, these works are endowed with a visionary dimension. As Fontana stated, ‘In future there will no longer be art the way we understand it… No, art, the way we think about it today will cease…there’ll be something else. I make these cuts and these holes, these Attese and these Concetti… Compared to the Spatial era I am merely a man making signs in the sand. I made these holes. But what are they? They are the mystery of the Unknown in art, they are the Expectation of something that must follow’ (Fontana, quoted in L. M. Barbero, op. cit., p. 47). Fontana often inscribed personal, philosophical or anecdotal details on the verso of his Attesa, endowing some of these works with specific autobiographical meanings or memories. In the case of the present work, Fontana has added the line, ‘Today I am having breakfast with the painter Clee’, a reference to the artist Clelia Cortemiglia, an artist who was a close friend and also student of the artist.

Lot 119. Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), Concetto spaziale, signed, titled and dated ‘l. fontana “concetto spaziale” 1953’ (on the reverse); signed ‘l. fontana’ (on a label with artist’s fnger print on the reverse), oil and glass on canvas, 23 5/8 x 28 ¾in. (60 x 73cm.). Executed in 1953. Estimate GBP 1,600,000 - GBP 2,500,000 (USD 2,091,200 - USD 3,267,500). © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

Provenance: Beatrice Monti della Corte Collection, Milan.

Private Collection (acquired from the above in the 1980s).

Anon. sale, Sotheby's London, 21 June 2006, lot 13.

Acquired at the above sale by the present owner.

Literature: E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, vol. I, Milan, 2006, no. 53 P 35 (illustrated, p. 263).

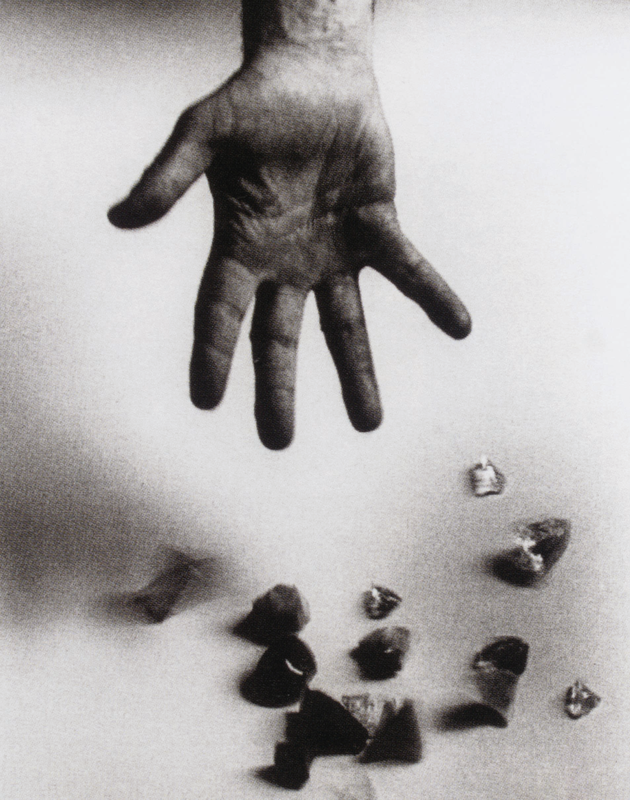

The hand of Lucio Fontana throwing stones, 1966. Photo Ugo Mulas © Ugo Mulas Heirs. All rights reserved.

Note: Against a pale backdrop, rough-hewn shards of red and pink glass glitter like gems in Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale, created in 1953. This introduces an intriguing and complex play of light and colour that is only accentuated by the contrast between the glimmer of the protruding glass and the radiating trails of holes that punctuate the surface. It was only a few years earlier that Fontana had begun to experiment with adding glass to his perforated canvases, and in the intervening time he had seldom turned to this variation, which called the Pietre, or ‘Stones.’

It was in 1953, the year that Concetto spaziale was made, that Fontana truly embraced this medium, creating a succession of elegant, refined works. In Concetto spaziale, that elegance is emphasised by the monochrome background, a factor that would become rarer the following year, as Fontana experimented with adding oil paint to the surface, introducing the swirls of impasto that would lead to his Barocchi. In Concetto spaziale, a more refined baroque is evoked through the pared-back presentation of holes and glass. It is a mark of the quality of Concetto spaziale that it was formerly in the collection of Beatrice Monti della Corte, the founder of the legendary Galleria dell’Ariete in Milan, where a decade later Fontana would exhibit his egg-shaped Fine di Dio series of paintings. Many of those celebrated paintings contained similar juxtapositions of holes and additional matter to the surface of Concetto spaziale, revealing the enduring power of this innovation.

It was only four years before Concetto spaziale was made that Fontana had begun to explore one of the innovations that was to become a defining factor in his career, the ‘hole.’ At that point, Fontana had already been long established as an artistic pioneer: born in 1899, he had already risen to prominence as a sculptor in the decade before the outbreak of the Second World War. Fontana had been born at the end of the Nineteenth Century in Argentina, and when war engulfed Europe, he returned to his native land for a number of years, exploring avant-garde concepts while teaching in Buenos Aires. On returning to Italy, he became the figurehead of Spazialismo, or Spatial Art.

While the works that arguably demonstrated his beliefs in finding modern media for a new modern age were his architectural installations, with looping spirals of fluorescent lighting and holes cut into walls and ceilings, he also began to create his trailblazing paintings such as Concetto spaziale. In these, he disrupted the traditional concept of the picture plane, first by penetrating the surface and then by adorning it with objects such as the glass shards that gleam so vigorously here. While the holes allowed space to be incorporated within the canvas, the use of the glass also allows Fontana to embrace the fourth dimension: time. After all, there is a constant change in the glimmer of reflected light and shadow that plays across the complex surface of each fragment. This introduces an almost performative aspect to Concetto spaziale, which shifts constantly according to its environs. Even the viewer becomes a part of the appearance of the work, reflected obliquely and in miniature in some of the tiny, irregular facets. The picture will look different according not only to where it is placed, but also by whom it is seen. In this way, Fontana is able to contrast the eternal nature of space and of his inerasable gestures with the transience of human existence, a factor that is only highlighted by the faint pink glow of the canvas itself, which recalls the flesh visible in so many of the martyred saints and long-dead heroes represented in the paintings and frescoes of the art historical canon with which Italy is so rich.

Fontana’s introduction of space into the picture surface marked a manner of Copernican reversal of received wisdom. In this, Fontana was exploring the new perspectives on the world being granted by fight, as planes, helicopters and rockets became increasingly an accepted fact of life. Granting a new understanding and vision of a realm that we now see as three-dimensional, yet had hitherto considered fat, Fontana’s opening of the picture surface was an analogue to the novelty of aerial views. With the addition of the glass fragments in Concetto spaziale, Fontana heightens the sense that we are somehow looking upon some distant terrain, a notion reinforced by the diagrammatic trails of holes, which follow undulating paths, rippling and radiating. The sense of movement invoked by the glass is also echoed in the composition, which recalls Futurist attempts to capture a sense of motion, for instance Giacomo Balla’s studies of swallowsflying. Like Balla, Fontana is harnessing a poetic transformation of the visual language of science and of engineering. Yet at the same time, the faint pink hue of the canvas and the glimmer of the glass both recall heavily-adorned reliquaries and the ornate interiors of baroque churches. In this way, Fontana is able to appropriate and disrupt an established aesthetic tradition in order to emphasise the modernity of his own vision. While this is expressed through an elegant and eloquent restraint in Concetto spaziale, a similar arsenal would be used just under a decade later in the famous Venezia series of paintings that Fontana created in 1961, in which holes and glass were placed on canvases that were often decorated with thick, elaborately-worked oils, often featuring a metallic sheen.

Lucio Fontana, Concetto spaziale, All’alba Venezia era tutto d’argento (At dawn Venice was all in silver), 1961. Private Collection. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2017.

As in the Venezia series which was the spiritual heir of Concetto spaziale and its sister works, this painting uses the glass for a number

of purposes. Introducing a form of ever-changing light-source into the surface of the picture, Concetto spaziale echoes on a smaller scale the vast architectural installations that Fontana was creating during the same period such as those for the 31st Milan Trade Fair which took place the same year, for instance the ceiling of the cinema in the Breda pavilion, which featured striations of perforations. Fontana at this point found himself at the cutting edge, introducing a new aesthetic to a world that had only recently been in the turmoil of a war which had seen technology pushed to incredible new scopes, from the improvements in fight to the horrors and wonders of nuclear science. It was only too apt that Fontana sought to express himself using new media such as glass—its reflective surface and coloured glow echoing the lights and buttons of control panels, hinting at the imminent Space Age. In Concetto spaziale, this element is located upon a monochrome canvas, resulting in an engaging fusion between the old and the new, between tradition and innovation.

Intriguingly, Fontana relied on a highly-traditional industry for the glass that he used in his Pietre. These fragments appear to have been sent to Fontana in bulk deliveries from foundries in Murano, the Venetian island considered one of the great centres of glass-making. These fragments would otherwise have been discarded, leftovers from the glass-making process, but now found themselves incorporated into his paintings, granted a new lease of life, a resurrection. As documented by Pia Gottschaller, decades after his death Fontana’s studio still contained masses of nuggets of coloured glass, a legacy of the creative process in making his Pietre (see P. Gottschaller, Lucio Fontana: The Artist’s Materials, Los Angeles, 2012, pp. 37-38).

Concetto spaziale was formerly in the collection of Beatrice Monti della Corte, a renowned Italian gallerist and patron of the arts. The retreat that she and her writer husband, Gregor von Rezzori, created in Tuscany saw writers such as John Banville, Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Hughes and Michael Ondaatje staying there during their lifetimes; since then, fellowships have been awarded to other authors including John Banville, Lawrence Osborne, Zadie Smith and Colm Tóibín. While the Galleria dell’Ariete which Monti helped found and direct was only seldom the venue for exhibitions of Fontana’s work, one of the exceptions being the Fine di Dio series a decade after Concetto spaziale was created, the artist was nonetheless a regular visitor. Indeed, Monti would herself recall, in an interview in Domus published in 1963, that Fontana was one of her invaluable supporters. ‘Fontana has always bought very many paintings, even by painters who were completely unknown at the time,’ she recalled. ‘This was very encouraging. And selling to him is a real pleasure, because he is always enthusiastic, ready to interest himself in everything’ (Beatrice Monti, quoted in ‘I mercanti d’arte’, Domus, No. 398, January 1963, p. 29). This enthusiasm was clearly reciprocated, as Monti owned several impressive works by Fontana, from a much exhibited 1934 sculpture to an oil from the 1960s.

Lot 117. Lucio Fontana (1899-1968), [Concetto spaziale], signed and dated ‘l. fontana 53’ (on the reverse), oil on canvas, 19 5/8 x 31 ½in. (50 x 80cm.) Executed in 1951. Estimate GBP 800,000 - GBP 1,200,000 (USD 1,045,600 - USD 1,568,400). © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

Provenance: D. Cavalli Collection, Pavia.

Anon. sale, Sotheby's Milan, 25 November 2003, lot 232.

Acquired at the above sale by the present owner.

Literature: E. Crispolti, Fontana. Catalogo generale, Milan, 1986, vol. I, no. 51 B 19 (illustrated, p. 104).

E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana. Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, vol. I, Milan, 2006, no. 51 B 19 (illustrated, p. 234).

Lucio Fontana in front of Concetto spaziale, 1958-59. Photo: Frank Philippi. © DACS 2018. Artwork: © Lucio Fontana/SIAE/DACS, London 2018

Note: Space penetrates a light pink canvas in the form of a constellation of holes in Lucio Fontana’s Concetto spaziale. Executed in 1951 –despite an inscription with a later date on the reverse – this is one of the earliest of Fontana’s Buchi, or ‘Holes.’ These were the works that he created from 1949, only two years earlier, in which he harnessed raw space within the fabric of a picture surface. This pioneering development would launch what would almost become a second career for Fontana, and over the following years, he would explore a number of variations upon the theme of the hole, for instance in his slashed canvases – the Attese – and the group of oval works entitled La fine di Dio. The catalogue raisonné of Fontana’s works lists only 30 other Buchi from before 1951; he created almost as many that year alone, showing the extent to which this new art form, initially experimental, was occupying an increasingly central position within his works. By the time Concetto spaziale was created, Fontana had still not exhibited any of his ‘holes’ – this would only take place the following year as part of a group show, and this great breakthrough would only be shown as a series in its own right in 1953. This locates Concetto spaziale at the very beginnings of the phase of Fontana’s career in which he created his most enduring legacy.

By 1951, when Concetto spaziale was executed, Fontana had been exploring the potential for ‘Spatial’ art in a number of ways and media. This included large-scale architectural installations, sometimes involving spirals of neon tubes, for instance in the grand staircase of the Palazzo dell’Arte during the course of the 9th Triennial in Milan that year. Fontana was an established sculptor, working in the round, but was increasingly aware of the increasing obsolescence of traditional art forms in the modern world that was growing around him. It was now that he turned to the traditional oil on canvas for his Buchi, creating his first pictures, yet reassembling their constituent parts in order to form something radical and new. He was emphasising the three dimensionality of the picture, highlighting the sculptural quality of the oil on canvas by opening it up and refusing to allow it to perform its time-honoured function as an inert surface on a wall.

The concept that drove this transformation was ‘Spatial Art.’ This was based in part on the changes that had occurred in technology, not least during the Twentieth Century. Now, with aviation becoming increasingly normal, man had managed to leave the surface of the planet and gain a new perspective on the world. With that release of the timeless bond between humanity and the Earth, which would probed even further by the launch of Sputnik into space in 1957, Fontana felt that it was time to create objects that embraced this new understanding of our place in the world. In Concetto spaziale, he managed to open up the picture surface, gouging it repeatedly to create a pattern of incisions that introduce space into the world of matter.

The cosmic theme of Concetto spaziale is extended by the constellation like composition that Fontana has created. To the right, tendrils spread out like the arms of the Milky Way. Meanwhile, dense clusters of smaller perforations add to the notion of distant systems of the night sky. However, these are all seen in reverse: the star-like holes introduce dark spots of infinity against the gentle warmth of the light pink surface, which itself faintly evokes the skin tones of so many Italian frescoes. This underscores the way in which Fontana is using Concetto spaziale to introduce the infinite scope of space into our realm, prefiguring the ‘rose’ monochromes of his friend, the younger artist Yves Klein, half a decade later. At the same time, the sheer sense of balance and rhythm brings an legance that has been noted by Enrico Crispolti when he listed Concetto spaziale among the most refined works of the series (E. Crispolti, Lucio Fontana: Catalogo ragionato di sculture, dipinti, ambientazioni, vol. I, Milan, 2006, p. 65).