Exhibition traces the emergence and influence of the nude in Renaissance art

LOS ANGELES, CA.- Drawing inspiration from classical sculpture and the study of the live model, Renaissance artists made the nude central to their art, creating lifelike, vibrant, and varied representations of the human body. This transformative moment is one that would shape the course of European art history and resonate through the present day.

On view at the J. Paul Getty Museum October 30, 2018 through January 27, 2019, The Renaissance Nude traces the rise of the nude over the course of a century with masterpieces made in Italy, France, Germany, and the Netherlands, from the early 15th to the early 16th century.

The Fall of the Damned, 1468–69, Dieric Bouts, oil on panel. On deposit from Musée du Louvre, Paris, to the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Lille, 1957. Image © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Jean-Gilles Berizzi

“Since the Renaissance, the nude has a central preoccupation of European Art. Yet until now no museum has undertaken a comprehensive examination of where and how the nude obtained its pre-eminent place in art practice and history,” says Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum. “In bringing together some of the greatest examples of Renaissance art from major European and American collections, the exhibition explores the various aspects of this enduring and captivating subject, allowing visitors an unprecedented opportunity to immerse themselves in one of Western art’s richest and most innovative traditions.”

Featuring more than 100 works in a variety of media, the exhibition casts its net widely. Painting and sculpture feature prominently, but so do drawings, illuminated manuscripts, and prints.

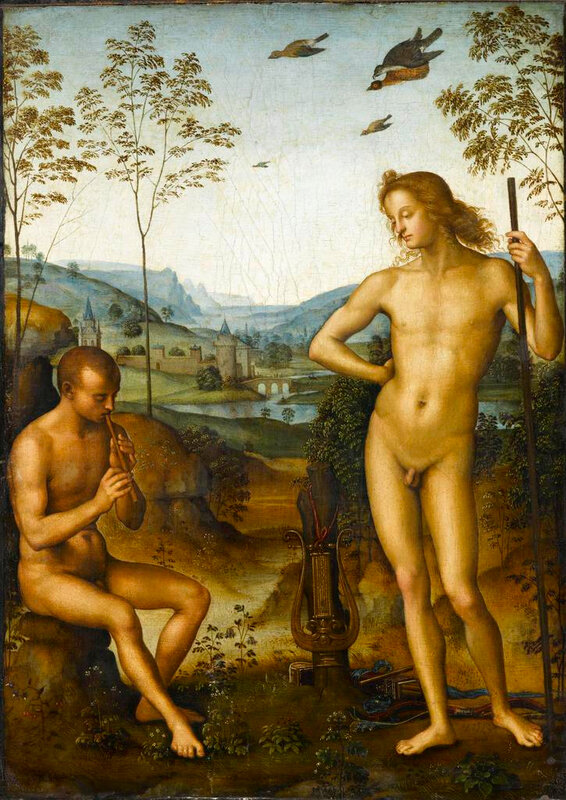

Apollo and Daphnis, about 1495, Perugino (Pietro Vannucci), oil on poplar. Musée du Louvre, Paris, Département des Peintures. Image © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY. Photo: Gérard Blot

The exhibition looks not only at the centers most often associated with the Renaissance nude – such as Florence, Venice, Rome and Nuremberg – but also Paris, Bruges, and lesser known centers of northern Europe. Artists represented include Leonardo da Vinci (Italian, 1452-1519), Raphael (Italian, 1483-1520), Michelangelo (Italian, 1475-1564), Titian (Italian, 1487-1576), Giovanni Bellini (Italian, about 1431/1436 – 1516), Albrecht Dürer (German, 1471-1528), Lucas Cranach the Elder (German, 1472-1553), Jean Fouquet (French, born about 1415-1420, died before 1481), Jan Gossart (Netherlandish, about 1478-1532), Hans Memling (Netherlandish, about 1440-1494), and many others.

“In taking a broad view, this exhibition embraces the tremendous variety of nudes in the Renaissance across subjects, functions, media, and regions, tracing numerous strands of development, some familiar and enduring, some parallel but separate, and others short-lived but prophetic,” said lead exhibition curator Thomas Kren.

Venus Rising from the Sea (Venus Anadyomene), about 1520, Titian (Tiziano Vecellio), oil on canvas. National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh. Accepted in lieu of Inheritance Tax by HM Government (hybrid arrangement) and allocated to the Scottish National Gallery, with additional funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Art Fund (with a contribution from the Wolfson Foundation), and the Scottish Executive, 2003

The Renaissance Nude is organized around five major themes: Christian Culture, Humanist Culture, Artistic Theory and Practice, the Abject Body, and the Nude in Personal Iconography. Within this framework, the exhibition looks at how artists across Europe approached particular subjects and themes, ranging from the body of Christ and St. Sebastian to the nude in the landscape to Venus, the power of women, and male sexuality. For example, no figure from ancient art and literature held more appeal for Renaissance artists than Venus, the Roman goddess of Love. By the 1520s, major artists in nearly every corner of Europe were representing her in different media. The very different paintings by Titian and Gossart in the exhibition emphasize the goddess’s beauty and charm; both also have sophisticated intellectual underpinnings in classical narratives that underscore the brilliance of each artist in making these sensual figures at once meaningful and alluring for the viewer.

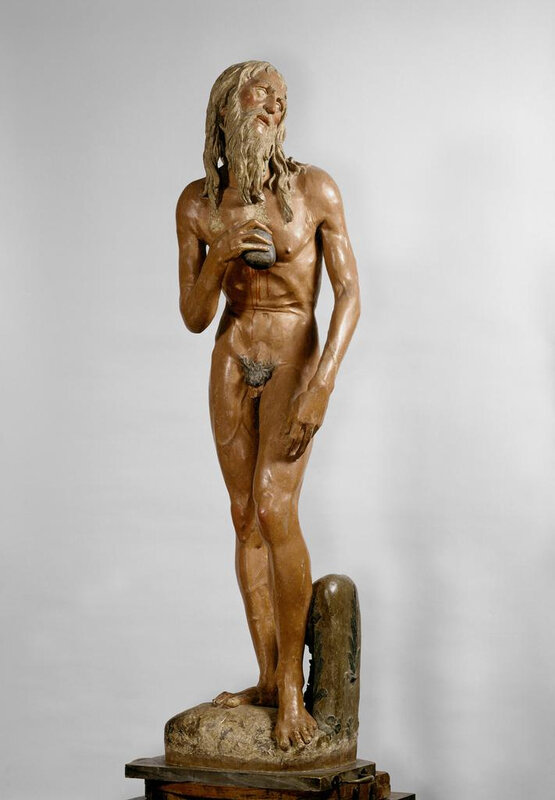

Saint Jerome, 1460–70, Donatello, polychrome wood. Pinacoteca Comunale, Faenza. Image: Scala / Art Resource, NY

The exhibition also draws upon recent scholarship that reexamines controversies around the nude, including the complex and varied reactions to individual works. For example, the show opens with a section on the nude in Christian art that establishes a broader cultural framework than humanist culture. The first image visitors will encounter is Cranach’s Adam and Eve, a narrative of the Fall of Man from the Hebrew and Christian books of Genesis that establishes bodily shame as originating in human history. In this way, the exhibition and accompanying catalogue explore the way not only humanist culture, new artistic attitudes, and spiritual beliefs shaped the appearance, meaning, and reception of the nude and continue to do so on our own time.

The Temptation of Adam and Eve, about 1510, Lucas Cranach the Elder, oil on panel. National Museum, Warsaw. Image courtesy of the Muzeum Narodowego w Warszawie

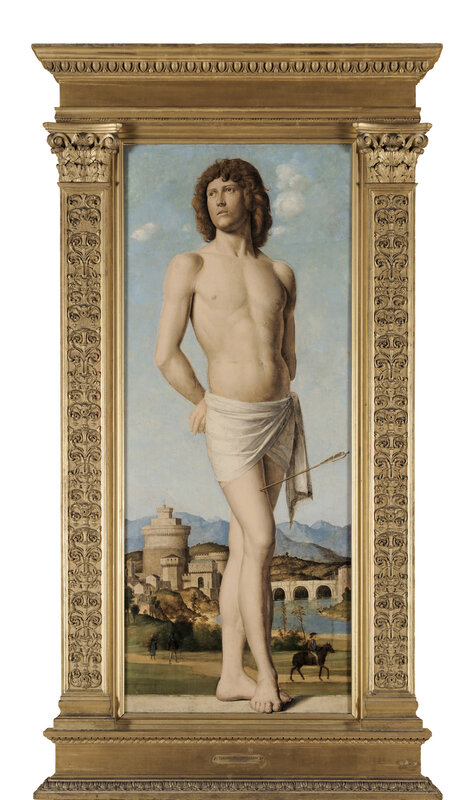

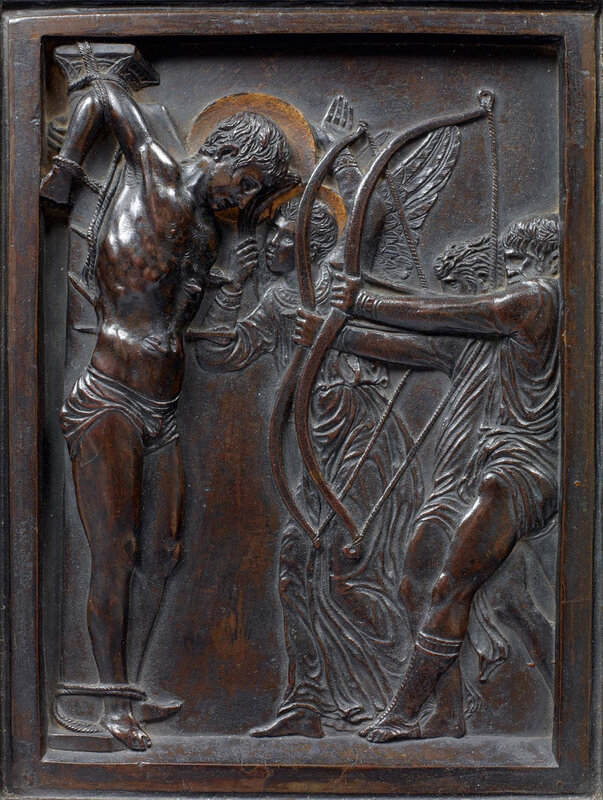

The Renaissance Nude also examines the relative prominence of male and female nudes at this time. Whereas female nudes by Titian, Giorgione, and Correggio (ill.), all represented in the exhibition, helped make the female nude one of the most popular themes in European art, the exhibition shows that in Italy, especially in the fifteenth century, the male nude was preeminent. As Italian artists from the 1460s began to be trained in drawing from live models, who for many decades were only male, the male nude became the most important subject for demonstrating skill in depicting the human figure. For example, Antonio Pollaiuolo’s large engraving from the 1470s, Battle of the Nudes, in which ten naked male figures are displayed in various postures, became famous throughout Europe. Reputed to be one of the first artists to dissect corpses for study, Pollaiuolo was painstaking in his rendition of the male form. Meanwhile, Saint Sebastian, always shown unclothed as he suffers the arrows of his persecution, was invoked for protection from the plague; its frequent recurrences created a large demand for images of Sebastian across Europe. As depictions by Donatello, Cima da Conegliano, and Martin Schongauer in the exhibition demonstrate, the subject offered an unparalleled opportunity to display mastery of the male form in a range of media.

Three Labors of Hercules, about 1530, Michelangelo Buonarroti, red chalk. Image: Royal Collection Trust / © Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018

The exhibition explores not only the very different notions of ideal beauty represented in Renaissance art but also the interest that artists often had in other types of unclothed bodies, including the ascetic, the emotionally distraught, and the aged. Donatello’s St. Jerome in Penitence, 1454-55, represents in wood a life-size sculpture of the nude saint scourging himself with a rock, his body showing the results of his denial of worldly pleasures, including conventional sustenance, and of exposure to the hardships of the desert in his pursuit of spiritual truths. By contrast, The Discovery of Honey, a painting by Piero di Cosimo from about 1499, is a bawdy classical scene that depicts Bacchus and his entourage of satyrs and maenads drunkenly stealing honey from a hive in a dead tree.

The exhibition is curated by Thomas Kren, with Jill Burke and Stephen J. Campbell and with the assistance of Andrea Herrera and Thomas de Pasquale.

Laura, 1506, Giorgione (Giorgio da Castelfranco), oil on canvas, originally mounted on a softwood panel. KHM—Museumsverband, Picture Gallery, Vienna. Image: KHM-Museumsverband / Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

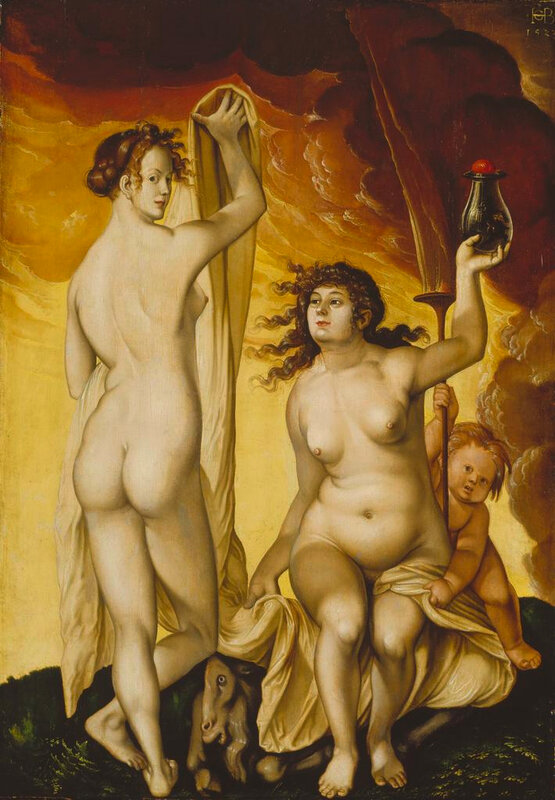

Two Witches, 1523, Hans Baldung (Grien), oil on panel. Städel Museum, Frankfurt. Photo: © Städel Museum - U. Edelmann - ARTOTHEK

Hercules and Antaeus, model created by 1511, cast 1519, Antico (Pier Jacopo Alari-Bonacolsi), bronze. KHM—Museumsverband, Kunstkammer, Vienna. Image: KHM-Museumsverband/Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

Saint Sebastian, 1478–79, Antonello da Messina, oil on canvas transferred from panel. Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Photo: bpk Bildagentur / Gemaeldegalerie Alte Meister / Elke Estel/Hans-Peter Klut / Art Resource, NY.

Saint Sebastian, 1500–02, Giovanni Battista Cima da Conegliano. Oil on wood, 45 7/8 x 18 1/2 in. Strasbourg, Musée des Beaux-Arts. Photo: M. Bertola.

The Martyrdom of Saint Sebastian, about 1450–52, Donatello. Bronze base in marble, 10 1/4 × 9 7/16 × 3 1/2 in. Institut de France, Musée Jacquemart-André, Paris, MJAP-S 764. Image © Studio Sébert Photographes.

Madonna and Child with Saints (Sacra Conversazione), about 1510, Moderno (Galeazzo Mondella). Gilt silver, 5 1/2 × 4 × 3/8 in. KHM-Museumsverband, Kunstkammer. Image: KHM-Museumsverband / Kunsthistorisches Museum, Wein.

Madonna and Child Surrounded by Angels, 1454–56, Jean Fouquet. Oil on panel, 36 1/4 x 32 7/8 in. Courtesy of Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen. Image © www.lukasweb.be–Art in Flanders vzw, photo Dominique Provost

Adam and Eve, 1504, Albrecht Dürer. Engraving, 9 13/16 x 7 9/16 in. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Art Museum Council Fund. Image: www.lacma.org.

Danaë, about 1530, Correggio (Antonio Allegri), oil on canvas. Galleria Borghese, Ministero dei Beni e delle attività culturali e del Turismo, Rome.

The Feast of the Gods (detail), ca. 1517–18, Raphael. Rome, Villa Farnesina, Loggia of Psyche. Photo: Miguel Hermoso Cuesta, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license (CC BY-SA 3.0). Source: Wikimedia Commons

Man of Sorrows, about 1430, Michele Giambono. Tempera and gold on panel, 18 1/2 x 12 1/4 in. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1906. Image: www.metmuseum.org

Christ on the Cold Stone, about 1530, Jan Gossart, oil on panel. Real Colegio Seminario de Corpus Christi de Valencia—Museo del Patriarca. Colegio del Patriarca Fotografía: Mateo Gamon.

The Flagellation, about 1525–30, Simon Bening. Tempera colors, gold paint, and gold leaf on parchment, 6 5/8 x 4 1/2 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. Ludwig IX 19, fol. 154v.

The Procession of Flagellants, in Belles Heures of the Duke of Berry, about 1405–8, Limbourg Brothers (Hermann, Paul, Jean), gold, silver, ink, and tempera colors on parchment. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cloisters Collection, New York, 1954 (54.1.1). Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY.

Bathsheba Bathing from the Hours of Louis XII, 1498–99, Jean Bourdichon. Tempera colors and gold on parchment, 9 9/16 x 6 11/16 in. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Ms. 79, recto.

Figure of a Woman Shown in Motion in Vier Bücher von menschlicher Proportion, 1528, Albrecht Dürer. Woodcut and letterpress, 13 1/8 x 8 3/8 in. Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, UCLA.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F08%2F50%2F119589%2F69969169_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F23%2F48%2F119589%2F122509465_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F94%2F05%2F119589%2F117582005_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F07%2F41%2F119589%2F112792921_o.jpg)