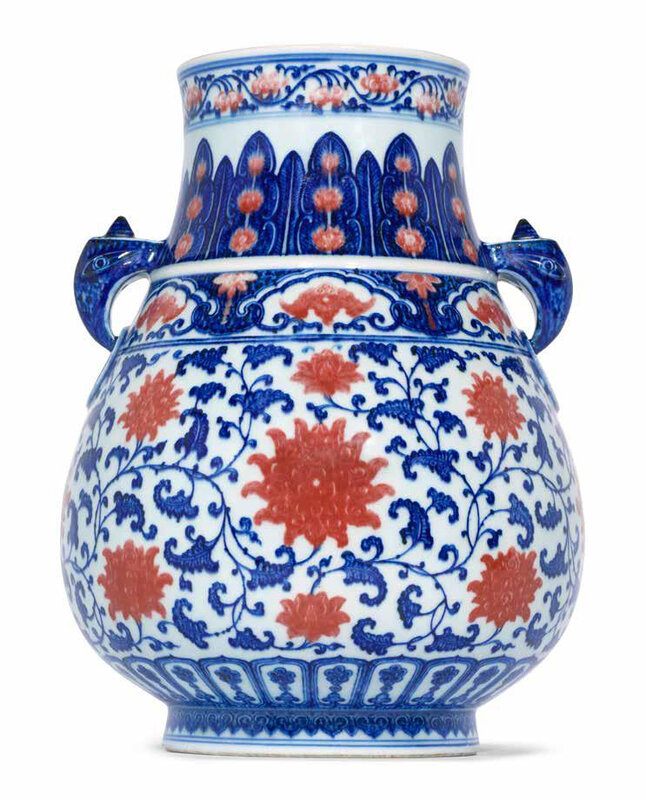

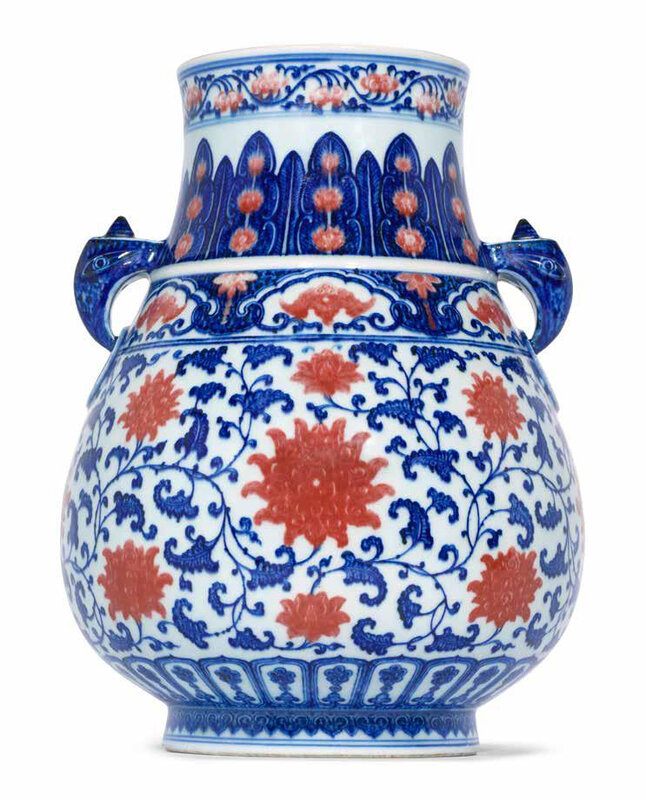

Lot 71. An exceptionally rare Imperial Ming-style underglaze-blue and copper-red vase, jiu'er zun, Qianlong seal mark and of the period (1736-1795); 34.3cm (13 1/2in) high. Estimate: HK$6,000,000.00 - HK$9,000,000.00 (€ 670,000 - 1,000,000). © Bonhams.

Of archaic bronze ovoid form, rising from the slightly spreading foot to the waisted neck, flanked by a pair of zoomorphic elephant ring handles set above a raised band around the shoulders, the body exquisitely painted with a continuous meandering foliate scroll in vibrant shades of underglaze-blue with 'heaping and piling' bearing lotus blossoms in three sizes superbly painted in vivid underglaze-red, all between lotus petal panels above the foot, each lappet enclosing a trefoil blossom and flower, and the shoulders set with a border of ruyilappets enclosing underglaze-red suspended flowers alternating with interlaced ruyi cartouches each enclosing an underglaze-red bat, the neck painted with upright plantain, each enclosing three graduated underglaze-red flowerheads, with a band of continuous foliate underglaze-blue scroll bearing underglaze-red lingzhifungus below the rim, the foot painted with a band of pendant ruyi, the base with the seal mark in zhuanshus cript.

Provenance: Tang Shaoyi (1862-1938), first Prime Minister of the Republic of China, 1912.

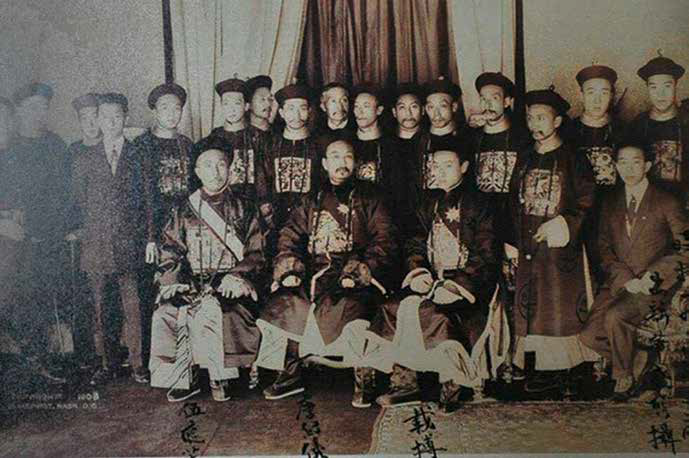

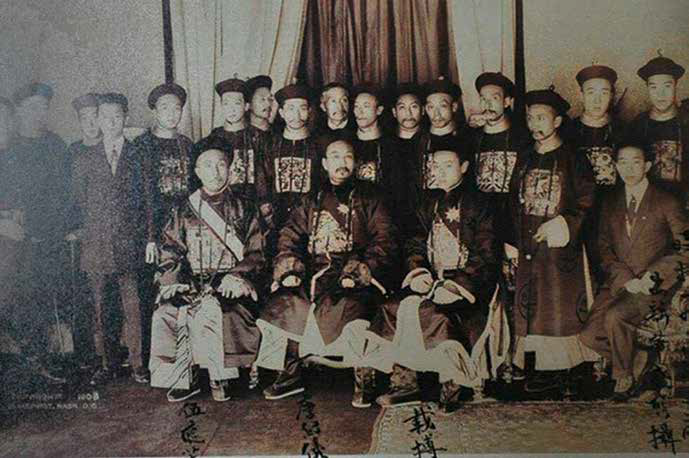

Tang Shaoyi, circa 1900s.

Tang Shaoyi (Tong Shao-yi) who was to become the first Premier fledgling Republic of China in 1912, following a successful civil service and diplomatic career during the twilight days of the Qing dynasty, was a passionate collector and connoisseur of Chinese porcelain. Chinese porcelain was to be used by him on at least one occasion as a diplomatic tool, and it was his love for Chinese porcelain and antiques which was used as a ruse for entry into his home and living room during his tragic assassination in 1938.

Tang was born in 1860 to a wealthy Cantonese family. Through his family relation Tang Ting-shu, a comprador in Jardine Matheson, and an old school friend of Yung Wing, a Yale University graduate and an official in the Qing government responsible for the programme to send Chinese students to study in the US, Tang was included amongst a select group of 120 boys and was sent to study in 1874.

Studying abroad was still disapproved of at the time and not considered the optimal way to improve the prospects of an individual or his family, in comparison with the traditional method of joining the Imperial Civil Service through success at the Imperial Examinations. However, Tang's family connections and their exposure to foreign firms convinced them of this as a positive prospect.

Tang went to grammar and high schools at Springfield and Hartford, followed by studies at Columbia University in 1880. However, in 1881 conservative elements in the Chinese government led to the students being recalled due to claims of them becoming over-Westernised and some converting to Christianity.

Following his return, in 1882 Tang began his diplomatic career in Korea, then a tributary of China, working against the expanding Japanese influence. It was during this period that he met General Yuan Shikai, then the Imperial Garrison Commander (and later first President of the Republic of China), who was impressed with Tang's abilities during an attempted Japanese coup. Yuan recommended Li Hongzhang, a high-ranking official and influential Viceroy of Zhili who directed China's foreign policy in Korea, to promote Tang to become consul in Korea and serve as Yuan's chief adviser. Thereafter Tang's career was closely related to Yuan's fortunes.

Yuan Shikai, between 1885 and 1894, depended on Tang to handle the diplomatic aspects in Korea and China's policy of asserting its suzerainty over Korea. However, these efforts ended in failure due to the Sino-Japanese war of 1894-1895. Following the war, Tang returned as the unofficial consul-general to Korea, until his recall in 1898.

In 1899 the Chinese imperial government appointed Tang as the managing director of the 600-mile Northern Railways. In this capacity Tang developed a lifelong friendship with Herbert Hoover, then working as a young engineer in Northern China and later to become the 31st President of the USA (1929-1933). Hoover described Tang as a man of great abilities, fine integrity and high ideals for the future of China. In May 1900 Yuan asked for Tang to be assigned to work in his province to handle diplomatic problems, many of which had arisen due to the Boxer Rebellion of 1900-1901. After that Tang was re-assigned to his previous Railways position. During the siege on the Westerners in Tianjin, Tang joined Hoover and his family, and was saved by Hoover from probable execution when wrongly accused by a Russian with colluding with the Boxers. During the siege, Tang's wife and one of his sons died from shellfire and Hoover helped Tang and his surviving children. Tang was able to repay this debt in part in 1928, when he came to the assistance of Hoover, clearing him of allegations of past corruption whilst working in China.

In the aftermath of the Boxer Rebellion, Yuan Shikai became the leading civil and military administrator and chief foreign-policy adviser to the Dowager Empress, Cixi. Yuan recommended Tang to the Imperial government as a man of superior talent and perception and well versed in diplomatic affairs. Following Li Hongzhang's death in 1901, Yuan was promoted to the position of Viceroy of Zhili and in turn appointed Tang in 1902 to his staff to the influential position of Chief Magistrate and Customs Superintendent for Tianjin which had foreign concessions by England, France, Germany, Russia, Japan, Austro-Hungary, Italy and Belgium and therefore required diplomatic relations with the foreign representatives in Tianjin. Despite the many lucrative possibilities, Tang was known for his honesty and respected by the foreign powers.

In 1904, following the British Younghusband expedition to Tibet – which China considered to be within its suzerainty - Tang was appointed Special Commissioner to Tibet. He visited India, as China's envoy, to negotiate the Tibet Convention, which was subsequently completed at Beijing, in April 1906. It is interesting to note that Chinese porcelain played a circumstantial role in these negotiations: one of the main British key-influencers was Lord Kitchener, Commander in Chief of the British Army in India, who preferred Tibet as a Chinese buffer state to German and Russian influence. Lord Kitchener was well known for his partiality to Chinese porcelain and Tang and his colleagues exchanged with him many valuable items during their stay (see a description of Kitchener's Kangxi and Qianlong porcelain noted by Sven Hedin in Trans-Himalayas – Discoveries and Adventures in Tibet, New York, 1909. ch.17, p.18). The agreement reached in Beijing in 1906 in effect restored British diplomatic recognition of China's sovereignty over Tibet.

Tang was strongly opposed to the Opium trade and its effects on China economically and on the population. Appointed junior vice president of the foreign ministry in 1905 he used his influence to gain foreign acceptance of the anti-opium programme. He approached the Empress Dowager personally and succeeded in persuading her to issue an edict in 1906 calling for an opium ban within ten years.

In 1906, he was appointed Vice-President of the Board of Foreign Affairs. Shortly afterward, he was made Director-General of all railways in China. In May of the same year, he was appointed Comptroller-General of the Revenue Council in Beijing, which was created to oversee the Imperial Customs service, which was managed and strongly influenced by foreigners and British in particular. Later he was promoted to Senior Vice-President of the Board of Communications whilst continuing to serve as Vice-President of the Board of Foreign Affairs. During this period, he negotiated foreign loans for railway development and succeeded in increasing Chinese influence within foreign firms which owned the railways.

Due to political intrigues against Yuan Shikai, Tang (being perceived as his henchman) was targeted by political rivals and the Dowager Empress was persuaded to issue an edict against him for nepotism. Tang reigned from his metropolitan posts but was then in 1907 assigned the governorship of Fengtien Province in Manchuria with diplomatic responsibility for all Manchurian affairs, during which he fought to maintain Chinese control and influence against Russian and Japanese encroachments.

In 1908 he was sent as a special envoy to the US to thank the United States Government for waiving part of the Boxer Indemnity, during which he visited the White House and met President Roosevelt; however, his main mission was to persuade the US to fund the development of Manchuria and promote a Sino-American-German understanding. Tang presented during the visit the Library of Congress with a set of the Chinese encyclopaedia Tu shu chi sheng ch'eng and a Kangxi period vase (see D.G.Hinners, Tang Shao-Yi and His Family: A Saga of Two Countries and Three Generations, Lanham, 1999, p.26).

Following the death of the Dowager empress and the Guangxu emperor, Tang was recalled to Beijing in early 1909. The government headed by the Prince Regent Chun dismissed Yuan Shikai and Tang, as well as removing him from his position as governor of Fengtian Province.

In August 1910, Tang was the prospective Vice-President of the Board of Communications, but was undermined by the Prince Regent and his vice-president by their policy of nationalisation of the railways which required mortgaging the railways to foreign banks, a policy which Tang opposed, resulting in his resignation in 1911.

After the outbreak of the Republican Revolution in 1911 Yuan Shikai re-appeared at the behest of the Prince Regent to take command of the Imperial Armies resisting the rebels and assuming power of government. When it became apparent that military power would not suffice to quell the rebellion, peace negotiations were held in Shanghai, headed by Tang representing Yuan Shikai's government. It is interesting to note that whilst negotiating for the government, according to certain family sources, Tang already held at the time Republican sympathies, assisting Sun Yat Sen (founding father of the Republic of China and first provisional President of the Republic of China) to avoid capture by the Imperial Secret Service.

On 13th February 1912, after the abdication of the last Manchu Qing dynasty emperor Puyi, Tang was appointed as the first Prime Minister of the Republic of China, with Yuan Shikai as the formal President. However, whilst official power rested with him, real political and military power was with the President. Disillusioned with Yuan Shikai's lack of respect for the rule of law, on 27th June Tang resigned the Prime Ministership, and was appointed High Adviser to the President on State Affairs. However, in 1915 he denounced President Yuan Shikai when the latter aspired to be emperor; and worked against his Imperial plan.

This period saw continuing attempts by Japan to increase its influence. On 21st May 1916 an interview of Tang was published in the New York Times. At the end of the interview with Tang by correspondents about Japan's attempts at expanding its influence, Tang ushered the correspondents into rooms across the hall displaying his porcelain collection. The correspondent described this in his own words:

It is perhaps the finest private collection in China. Pieces of Sung and Ming, of Clair de Lune, of San de Boeuf, of wonderful peach bloom, and blue and white, were arranged around the walls on shelves, each with its carved black teakwood stand and its pink satin-padded box. He fondled each piece with the loving fingers of a connoisseur ... He lifted down a great cool green vase of sea nympth's pallor, with marvellous dragons twisting themselves around it in relief – imperial dragons, with five claws holding the precious jewel. "This is my favourite," he announced. "It is very rare, I have had my agents looking for the mate to it all over the country for five years. Wouldn't J. P. Morgan have loved to get hold of it?".

After the death of Yuan Shikai in 1916, Tang was appointed Minister of Foreign Affairs; but only proceeded as far as Tianjin and returned to Shanghai before the assumption of office, on account of opposition in Beijing. He supported the Beijing Government for the dissolution of Parliament in 1917, when it refused to pass the bill urging war with the Central Powers. He was appointed by the Southern Government, headed by Sun Yat Sen, in the spring of 1919, to head the Southern peace delegation to the conference for the settlement of China's internal troubles, which commenced in 1917.

Tang served as a member of the Military Government at Canton, from 1911 to 1922. On 5th August 1922, President Li Yuanhung appointed Tang as Premier to succeed Dr. W.W. Yen, but Tang refused to go to Beijing and turned the appointment down. In 1924, he also refused an offer to be Foreign Minister under warlord Duan Qirui's provisional government in Beijing.

In 1936 Tang was appointed to membership in the State Council. Japan's undeclared war on China began in July 1937. Because of his advanced age (77) and ill health, Tang did not follow the National Government move to Western China but took up residence in the French Concession in Shanghai. The Japanese military were searching for prestigious Chinese political figures to head two puppet governments which they established in Beijing and Nanjing in early 1938. In the Shanghai area it was rumoured that they approached the now elder statesman Tang Shaoyi, despite his strong denials in the press for any such involvement with the Japanese. The Chinese government reacted to the Japanese intrigues by encouraging the assassination of high-ranking officials thought to collaborate with the invaders, and in many cases such assassinations were carried out by hit squads from Chiang Kai-shek's secret police and intelligence services, commonly known as the Juntong.

Tang's tragic death was circumstantially connected to his passion and collecting of Chinese porcelain. On 30th September 1938, whilst he was preparing for the wedding of one of his daughters, the team of assassins gained access to his home through the familiarity of the household with two of them, on the pretext of wanting to show Tang antique porcelain and works of art. When they met Tang in his living room, using a ruse to be alone with him (whilst Tang was paying attention to the antiques) they seized the opportunity to deal him mortal wounds, from which he tragically died later the same day.

Tang's assassination shocked many members of the Kuomintang, who directly asked Chiang Kai-shek why he was assassinated. The secret police could not provide any evidence of treasonable intentions by Tang and demands were made that his assassins be brought to justice. Indeed, Chiang issued a proclamation commending Tang for a lifetime of meritorious service and presented exhibits of his career to the National History Museum, sent condolences and gifts to his relatives and urged the French authorities to search for his assassins, though these were never captured.

Whether or not Tang negotiated with the Japanese to become a Premier of one of the puppet governments is in debate. It has also been suggested that Chiang Kai-shek may have covertly encouraged Tang to enquire about the Japanese peace terms and that he then authorised the assassination as a cover-up in case it tarnished his image as national symbol of Chinese resistance to Japan.

Tang Shaoyi's prestige as a public figure was consistently very high, he was well-known and hugely respected for his diplomatic skills, patriotism, intellect, charm and strong sense of integrity, as demonstrated in his repeated rejection of offers of high office from political elements he disapproved of.

For additional reading see: D.G.Hinners, Tang Shao-Yi and His Family: A Saga of Two Countries and Three Generations, Lanham, 1999.

L.T.Sigel, unpublished Ph.D thesis, T'ang Shao-yi (1860-1938): The Diplomacy of Chinese Nationalism, 1900-1911, Harvard University, Cambridge Mass., 1972.

Tang Shaoyi and Chinese delegation in Washington D.C., 1908; first row from left to right: Wu Tingfang, Tang Shaoyi, Prince Zaibo.

Note: The present vase is an exquisite masterpiece exemplifying the highest level of porcelain production accomplished at the height of the Qing dynasty during the celebrated Qianlong reign. The control during the firing of copper-red proved a significant challenge to potters at the Imperial kiln in Jingdezhen from the days of the first Ming emperor, Hongwu, and earlier, until the end of the Qing dynasty, making the Tang Shaoyi vase with its superb vivid underglaze-red lotus blossoms, bats, flowers and lingzhi, elegantly contrasted with the vibrant underglaze-blue, a very rare example.

The vase is unique in its combination of form and design, and no other similar vase would appear to have been published.

It combines the Qianlong emperor's fascination with the past as well, with the direct continuity of style from Imperial porcelain produced during the reign of his father, the Yongzheng emperor, and the exacting standards and masterful achievements of the master potters in the Imperial kiln in Jingdezhen. Successful firing of copper-red, particularly for larger pieces, most likely required numerous attempts before achieving a single successful example, let alone one such superbly-controlled brilliant underglaze-blue and strong underglaze-red as the present example. The direct continuity in style from the Yongzheng period combined with the highest standards set and accomplished in this vase, strongly suggest that it was produced during the residency of the most famed supervisor of the Imperial kilns in Jingdezhen, Tang Ying (1682-1756).

The hu form of the vase, also known as 'ox-head' form, is inspired by archaic bronzes of the Warring States period; see an example published by Ding Meng, Collections of the Palace Museum: Bronzes, Beijing, 2007, pp.236-237, no.156. The zoomorphic elephant handles were inspired by archaic bronzes of the early and late Western Zhou dynasty; for two related examples see Chen Peifen, Ancient Chinese Bronzes in the Shanghai Museum, London, 1995, pp.64 and 69, nos.37 and 42.

In the Qing dynasty, this form was first introduced during the reign of the Yongzheng emperor who is known to have personally supervised the production of objects for the Imperial Court and which in many cases included porcelain imitating both ancient forms and glazes reinterpreted with innovative aspects in material, form and decoration.

This archaism can be interpreted as the attempt of the rulers of the foreign Manchu Qing dynasty to demonstrate continuity from ancient times, symbolising their legitimacy and Mandate from Heaven to rule. Such archaism also embodied the emperor's wish for inspiration from the perceived morality and virtues of ancient days. For a related underglaze-blue and copper-red hu 'lotus-scroll' vase, Yongzheng mark and period, see Feng Xianming and Geng Baochang, eds., Selected Porcelain of the Flourishing Qing Dynasty, Beijing, 1994, p.167 no.11. However, this vase differs in the form, handles and secondary border designs. Compare also a related blue and white hu 'lotus-scroll' vase, Yongzheng mark and period, with similar elephant handles, which was sold at Sotheby's Hong Kong, 29 October 1991, lot 133, illustrated in Sotheby's Hong Kong: Twenty Years, Hong Kong, no.176. The direct continuity in design of the present vase from the Yongzheng reign is also demonstrated in the underglaze-blue and copper-red lingzhi scroll border, as can be seen on a yuhuchunping and a garlic-mouth vase, Yongzheng marks and period, the former from the Qing Court Collection, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Blue and White Porcelain with Underglaze Red (III), Hong Kong, 2000, p.214, no.195, and the latter illustrated by Lee Hong, ed., Porcelains from the Tianjin Municipal Museum, Hong Kong, 1993, no.146. See also a similar lingzhi scroll border on an underglaze-blue and copper-red garlic-mouth vase, Qianlong seal mark and period, from the Shanghai Museum, illustrated by Wang Qingzheng, Underglaze Blue and Red, Hong Kong, 1987, no.126. Compare also the related form and similar handles on a blue and white 'lotus-scroll' hu vase, Qianlong mark and period, illustrated by P.Y.K.Lam, ed., Ethereal Elegance: Porcelain Vases of the Imperial Qing, The Huaihaitang Collection, Hong Kong, 2007, no.101 (30cm high), and another but larger example (47cm high), Qianlong seal mark and period, from the Qing Court Collection, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Blue and White Porcelain with Underglaze Red (III), Hong Kong, 2000, no.136. Similarly shaped vases, were also made in monochrome glazes, see Jun-type vase, Qianlong seal mark and period, illustrated in Chinese Porcelain: The S. C. Ko Tianminlou Collection, Part II, Hong Kong, p.226, no.162.

The lotus is one of the Eight Buddhist Emblems, bajixiang symbolising purity. The lingzhi fungus and ruyi-heads both represent the wish for long life. Combined with the bats, the decorative symbolism is one of auspicious wishes for long life and purity.

IMPERIAL JIU’ER ZUN VASES FROM THE QING COURT COLLECTION

Porcelain utensils are still among the most commonly used objects in the life of both ancient and modern people. It was also the main material for most utensils at the Qing Imperial Court (1644-1911). Whether the porcelain was used in daily life at Court, displayed in the palaces, used as temple furnishings or in rituals, or simply exchanged as gifts, a vast number of ceramics were used during the Qing dynasty. To meet this high demand, the Qing Court continued the system of Imperial kilns and porcelain factories in Jingdezhen, Jiangxi Province, which had begun in the Ming dynasty, to make porcelain specifically for Imperial use. As early as the Shunzhi reign at the beginning of the Qing dynasty, the Imperial kilns had a limited fixed scale of production. In the ‘Regulations and Precedents of the Imperial Household Department, Made by Imperial Order’ (Qinding zongguan neiwufu xianxing zelie), it is recorded:

‘In the tenth month of the nineteenth year of the reign of Emperor Kangxi (1680), by his Imperial majesty’s command, an official from the Imperial Household Department, as well as an official from the Department of Works together with a scribe each were dispatched to use the money and grain from the Jiangxi State Provincial Warehouse to produce porcelain utensils for use in the Great Within. The Department of Works will compensate for revenue used.’ 1

From then on, the Imperial Kilns officially resumed production. Until the end of the Qing dynasty, the Imperial kilns received large orders of porcelain utensils from the Imperial family. The Forbidden City, as the main Imperial palace of the Qing dynasty, was undoubtedly the final destination for many of these products.

Today, there are more than 300,000 pieces of Imperial porcelain from the Qing Court Collection preserved in the Palace Museum. The cultural relics tagged ‘Qing Court Collection’ refer to those pieces originally in the Imperial collections in the Forbidden City and several other Qing royal palaces such as the Summer Palace, the Chengde Mountain Resort and the Shengjing Palace (now the Shenyang Palace Museum) and were inherited by the current Palace Museum. Overall, the Qing Court Collection of porcelain represents a variety of different periods and eras, elegant and classical forms, stunning decoration and exquisite craftsmanship. The collection not only allows us to study Qing Imperial porcelain; it is also the most valuable source for studying the history of Qing porcelain production.

Imperial porcelain from the Qing Court Collection, specifically from the Qianlong period (1736-1795), both in terms of quantity and quality can justly be called the crown of the collection. The Qianlong era represented the peak of political, economic and social development in the Qing dynasty. The economy prospered, and the empire was at its strongest. Thus, the Imperial kiln had strong financial backing and could be prolific in its output. Moreover, the Qianlong emperor was diligent in government affairs and was also passionate in his pursuit of culture and art. He was skilled in calligraphy and painting, good at poetry and writing, and was obsessed with antiques and porcelain. After he succeeded to the throne, he continued to apply himself to ensuring a healthy production of porcelain.

While fortunate in having the craftsmanship and skill of the esteemed master technocrat Tang Ying (1682-1756) in charge of the Imperial porcelain works, Qianlong also inherited the tradition from the Kangxi and Yongzheng emperors of directly intervening and micro-managing the production of porcelain. He regularly issued decrees ordering paintings to be used as models or that new models for porcelain be made. After personally inspecting the prototype it would be sent to the Imperial porcelain factory and kiln for firing. This process has been preserved in the Qing Imperial archives. For example, in the Imperial Household’s archive of ‘Qing Files of Labour and Works’ (Gezuo chengzuo huoji qingdang) it is recorded under ‘Jiangxi’ that in the seventh year of the Qianlong reign (1742):

‘On the eighth day of the fourth month, by order of the Emperor, Grand Minister Haiwang delivered a painting of a ‘clear-sky white’ ground underglaze red dragon and horse wall vase to Tang Ying in Jiangxi as a model to fire several pieces to be sent up. It was so decreed.’ 2

In addition to this, on the same section it is recorded:

‘On the twenty-ninth day of the eighth month, treasurer Bai Shixiu came to say that Eunuch Gao Yu delivered a blue and white double-cloud handled hexagonal zun vase, by Imperial order. This vase’s form and pattern was very good; Tang Ying, according to this model produced several more pieces. However, because the body of the dragon on the belly of this vase was not correct, it was corrected. The handles too were not good and Tang Ying improved the form of the handles, whereupon he fired several more pieces. Only when the dragon on the belly did not need changing, and when the right pattern and form was achieved, was it sent. It was so decreed.’ 3

From this we can see that during the Qianlong era the manufacture of Imperial porcelain, in almost all aspects from the shape to the decoration, was strongly influenced by the emperor’s aesthetic taste and standards, forming a distinctive style unique to his era. Fundamentally, however, it was a continuation of his father, the Yongzheng emperor’s style of Imperial intervention and supervision that ensured the ‘Inner Court manner’. According to the Imperial Household Department’s records, the ‘Files of Handicraft’ (Huoji dang), in the fifth year of the Yongzheng emperor’s reign (1727), on the third day of the third month:

‘A decree came from the Yuanmingyuan [i.e. the Yongzheng emperor], passed on by Minister Haiwang, stating: keep the models from previous projects We have worked on. If the models are not kept, it is feared that later, it will not achieve what was originally intended. Although We see that those works made previously by the Imperial Workshops that were good are few, they still conformed to the Inner Palace style. Recently, although the craftsmanship is ingenious, many have the air of the ‘Outer’. When you manufacture items do not lose that Inner Court manner.’ 4 (Fig.1)

The jiu’er zun vases (literally, ‘turtle-dove’ handled zun) from the Qing Court Collection offer a perfect example of Qing porcelain embodying the characteristics of the so-called ‘Inner Court manner’.

The jiu’er zun vases made in the Imperial porcelain manufactory in Jingdezhen for the Court, were based on models from the Yongzheng period, which in turn were based on archaic bronze zun and hu vessels from the Warring States, Qin and Han periods. One can see many different versions and styles of this form of vase from the Yongzheng and Qianlong periods, including jiu’er zun vases in blue and white, Ru style glazes, white Ding style glazes, flambé glazes and tea-dust glazes, and other varieties. The sizes of these vases can be divided into two categories: one is more than 45cm in height and approximately 22cm in diameter, the second type are about 20cm in height and approximately 7 to 8cm in diameter. Below are some related examples of jiu’er zun vases from the Qing Court Collection:

(1) A flambé glazed jiu’er zun vase, Qianlong mark (Fig.2), ‘water’ (shui) 3315, height 20.3cm, diameter 7.7cm, foot diameter 8.3cm. The whole body covered in a flambé glaze of purple-red colour with streaks of blue. The base with a Qianlong six-character mark. This vase was originally in the Hall of Supreme Principle (Taiji dian) in the Forbidden City. 6

2) A Ding style white glazed jiu’er zun vase with embossed archaistic dragons, Qianlong mark (Fig.3), ‘remain’ (liu) 14031, height 20cm,diameter 7.6cm, foot diameter 7.8cm. The whole body is covered with a white glaze with a yellowish tint. The exterior decorated with archaistic dragons in low relief, the neck with wave patterns, the shoulders decorated with a ‘bow-string’ chord, the base with an incised Qianlong six-character mark. This piece was originally either in the ChengdeMountain Resort or Shengjing Palace (Shenyang Palace).

3) A Ru style jiu’er zun vase, Qianlong mark (Fig.4), ‘mark’ (hao) 2089, height 47cm, diameter 21.5cm, foot diameter 22cm7. The exterior and interior covered in an azure-blue glaze, the foot ring painted brown. The base with an underglaze blue Qianlong six-character mark. This piece was originally housed in the west wing of the Ningshou Mansion on Tingdong street outside the Forbidden City. 8

(4) A blue and white jiu’er zun vase, Qianlong mark (Fig.5), ‘mark’ (hao) 1711, height 45.5cm, diameter 21cm, foot diameter 22.5cm. The mouth and foot rims decorated with foliate scrolls, the neck with a band of pendant ruyi-heads. The body vividly painted with meandering lotus scrolls, the handles in underglaze blue. The base with an underglaze blue Qianlong six-character mark. This piece was also originally housed in the west wing of the Ningshou Mansion on Tingdong street outside the Forbidden City. 9

According to the statistics of cultural relics in the Forbidden City, there are eight jiu’er zun vases from the Qianlong period that were in the Qing Court Collection. Regardless of the size, the shape had to be consistent, with wide open mouth, broad neck, sliding shoulders and turtle-dove handles, a low centre of gravity and circular foot. They all have excellent glazes that display the rich range and superlative technology and craftsmanship of the time. Of these, the blue and white varieties share regular patterns commonly used on Qing dynasty Imperial porcelain, reflecting the fascination for antiquity as well as the innovations of the Qianlong period and the strict reverence for the ‘Inner Court manner’ style of the time.

1. ‘shaozao ciqi’ in Qinding zongguan neiwufu xianxing zelie guangchu si, juan 1.

2. Qing gong neiwufu zaobanchu dangan zonghui, juan 11, p.75.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid, juan 2, p.646.

5. Gugong wupin diancha baogao. When the Palace Museum was established in 1924, all the pieces formerly in the Qing Court Collection were inventoried according to the Thousand Character Essay (Qian zi wen). Each character corresponded to a palace or location in the Forbidden City. For example, the character li 麗 corresponds to the fifth ‘antique house’ of the five inner courts of the Forbidden City. Therefore, based on the Qian zi wen, one can find the original location of a piece.

6. Gugong wupin diancha baogao di san pian, vol.1, juan 3, p.6.

7 Ibid., di si pian, vol.2, juan 1, p.107.

8 Ibid., p.109.

9 Ibid., p.86.

Bonhams. Fine Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art, Hong Kong 27 november 2018.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_c453b7_439605604-1657274835042529-47869416345.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_59c6f0_440358655-1657722021664477-71089985267.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_07a28e_440353390-1657720444997968-29046181244.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_0b83fb_440387817-1657715464998466-20094023921.jpg)