An ancient mythological creature that appears in Chinese literature at least as early as the Warring States period (481-221 BC), the chilong is characteristically presented as a young, playful creature. When shown singly, as in this dish, it typically turns its head to look over its back and toward its tail, thus assuming a C-shape. In other instances, the chilong may be depicted together with one or two additional chilong, and occasionally together with a mature dragon, or long, the mature dragon typically identified as the mother; in such « family presentations », the several chilong generally frolic around their mother, playing with each other and even climbing over their mother’s back.

Like its close relative, the mature long dragon, the chilong is an auspicious emblem that denotes high status and conveys to the viewer every good wish for success and prosperity. Moreover, the Lushi Chunqiu – a text written around 239 BC by Lu Buwei (290-235 BC) and whose title can be translated as Master Lu’s Spring and Autumn [Annals] – attributes to Confucius (551-479 BC) a quote in which he compares long « dragons », chi « hornless dragons », and yu« fish » and then likens himself to a hornless dragon: « Master Kong [i.e., Confucius] said, ‘The dragon eats and swims in clear water; the hornless dragon eats in clean water but swims in muddy water; fish eat and swim in muddy water. Now, I have not ascended to the level of a dragon, but nor have I descended to that of fish; perhaps I am a hornless dragon!' » (Quotation adapted from John Knoblock and Jeffrey K. Riegel, The Annals of Lu Buwei, Stanford, 2000, p. 505.) Confucius’ likening of himself to a chilong assured that creature an elevated status in Chinese mythology as well as an honored place in the repertory of decorative-arts motifs.

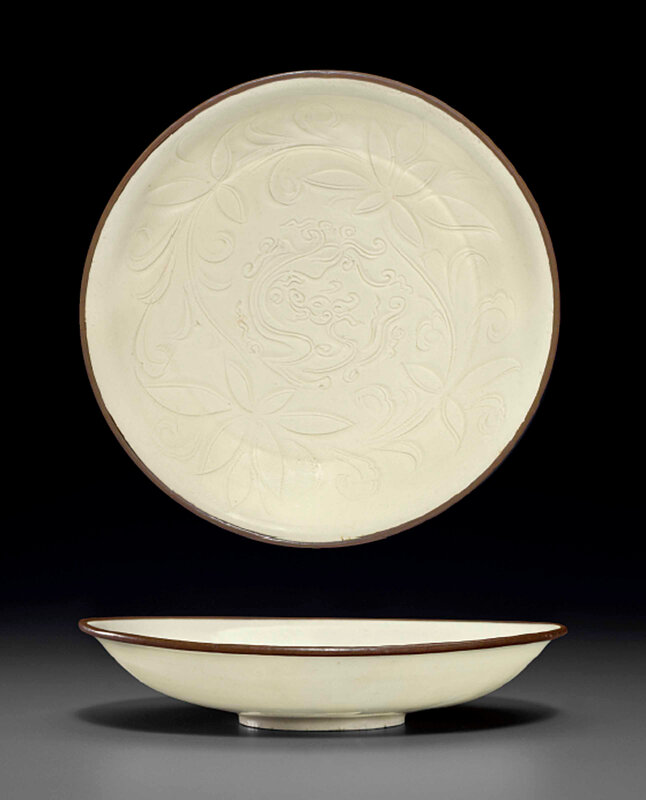

Although the lotus scroll that embellishes this dish is the most typical motif in Ding ware produced during the Northern Song period (960-1127), the chilong, by contrast, is a motif only rarely encountered amongst Song ceramics. This dish’s chilong-and-lotus decor is virtually identical to that on a bowl in the National Palace Museum, Taipei. (See Gugong Songzi Tulu (Illustrated Catalogue of Sung Dynasty Porcelain in the National Palace Museum), Dingyao – Dingyaoxing (Ding Ware and Ding-type Ware), Tokyo, 1973, no. 44.) It also relates closely to that on a bowl in the Palace Museum, Beijing. (See Zhongguo Taoci Quanji / Chugoku Toji Zenshu (A Compendium of Chinese Ceramics), vol. 9, Dingyao / Teiyo (Ding Ware), Shanghai and Tokyo, 1981, pl. 77.) In addition, the decorative scheme on this dish is also very close in style and general appearance to that on two bowls formerly in Swedish private collections: one formerly in the Carl Kempe Collection, Stockholm, and one formerly in the J. Hellner Collection, Stockholm. Both bowls are published by Jan Wirgin in Sung Ceramic Designs, London, 1979, pp. 138-39, Type: Ti 27, pl. 69a (Ex-Kempe Collection) and pl. 69b (Ex-Hellner Collection).

Collectors of the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties ranked Ding ware among the « five great wares of the Song », along with Jun, Ru, Guan, and Ge wares. Celebrated for their porcellaneous white wares, the Ding kilns also produced pieces with russet and black glazes. Although not imperial kilns per se – that is, they were not operated by the government and did not produce ceramics exclusively for the imperial household – the Ding kilns nevertheless supplied substantial quantities of ceramic ware to the palace in the late tenth, eleventh, and early twelfth centuries.

Produced at a number of small kilns in Quyang county (in central Hebei province, about 100 miles to the southwest of Beijing), Ding ware is so named because Quyang county fell within the Dingzhou administrative district during the Northern Song period (960-1127). As evinced by this dish, elegant forms derived from contemporaneous silver and lacquer typify the ware, as do thin walls that result in pieces of unusually light weight. The smooth, fine-grained bodies of Ding ceramics are pure white; composed almost entirely of kaolin, the bodies are only slightly translucent, transmitting a warm orange light when they transmit light at all. Thin and pale, their ivory-hued glazes impart a warm tone. Connoisseurs early on recognized that runs of glaze, which they termed « tear drops », characteristically appear on the exteriors of Ding vessels, as they do on this shallow dish.

Ding vessels from the tenth and early eleventh century are usually undecorated, though they often suggest natural forms, circular bowls with notched rims suggesting open blossoms, for example, the notches separating one petal from the next. Ding vessels from the late eleventh and early twelfth century typically sport incised and carved decoration, while those from the mid-twelfth through the thirteenth century characteristically boast mold-impressed decoration.

From the late eleventh century onward, white Ding bowls and dishes were stacked upside down in their saggars, or ceramic firing containers, in order to increase kiln efficiency; their mouth rims were wiped free of glaze slurry before firing to prevent the bowls from fusing to the saggar in the heat of the kiln. The bowls and dishes were banded with metal after firing to conceal the unglazed rim.

Ding wares were fired in small, mound-shaped kilns known in Chinese as mantou yao, or « dumpling kilns », the name resulting from their similarity in shape to that of Chinese dumplings, or mantou. Although fired with wood in the late Tang (618-907) and Five Dynasties (907-960) periods – their earliest phase of development – the Ding kilns came to rely on coal as fuel beginning in the tenth century. As a reducing atmosphere is difficult to achieve when firing with coal, most Northern Song Ding vessels were fired in an oxidizing atmosphere, which explains the ivory hue of the glaze.

Robert D. Mowry

Alan J. Dworsky Curator of Chinese Art Emeritus, Harvard Art Museums, and

Senior Consultant, Christie’s

Christie’s. FINE CHINESE CERAMICS AND WORKS OF ART, 18 – 19 September 2014, New York, Rockefeller Plaza.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F07%2F83%2F119589%2F129627729_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F37%2F119589%2F129627693_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F65%2F12%2F119589%2F128670418_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F10%2F27%2F119589%2F128667786_o.jpg)