One of the best Delftware collections of the past decades at TEFAF Maastricht

AMSTERDAM.- At the upcoming edition of TEFAF Maastricht, Amsterdam based dealer Aronson Antiquairs will bring to market one of the best Delftware collections of the past decades. The collection, which was in a large part assembled by private Dutch collectors over a period of approximately thirty years, comprises many highlights. Although it has its center of gravity in the eighteenth century, it also contains several wonderful early objects.

“What we can bring to an art fair like TEFAF, really depends on what we can source in the year, or sometimes years, running up to an event like this” says Robert Aronson. “Although we work year round to find the best Delftware objects, good objects are so incredibly rare, that sometimes we cannot even get a hold of them” Aronson continues. The collection to be seen at TEFAF this year can rival with ancients collections such as those of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague or the Musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire in Brussels.

This collection was compiled with great love and enthusiasm under the auspicien of the Aronson family. The Dutch collectors did however buy from several sources and were able to therewith bring together such a diverse and high quality collection. Some of the highlights are ‘The Stella Ewer’ made in Delft around 1675 and formerly owned by the renowned Dutch entrepreneur Dr. F.H. Fentener van Vlissingen (1882-1962); the brown glazed garniture produced in Delft around 1715 of which the only comparable set, but lacking its covers, is in the aforementioned Brussels museum; the wonderful and very rare pair of polychrome hen tureens and covers on stand made by Jacobus Adriaensz. Halder, the owner of De Grieksche A (The Greek A) factory from 1764 until 1768; or the pair of polychrome crouching hare tureens and covers, Delft, circa 1765, which in 1929 were exhibited at an exhibition at the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.

‘The Stella Ewer’, Delft, circa 1675. Marked IW in blue for Jacob Wemmersz. Hoppesteyn, the full owner of Het Moriaenshooft (The Moor’s Head) factory from 1659 until 1671, and succeeded by his widow Jannetge Claesdr. van Straten through 1686. Height: 23.1 cm. (9.1 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

The teardrop-shaped body painted on one side with three putti watching and helping a fourth blowing bubbles near a classical column, and on the reverse with two putti watching two others playing a game of bowls, all in a continuous Italianate hilly landscape beneath a border of blossoms and fruiting grapevines, the front of the slightly flaring neck with a scrolling foliate device, and the loop handle with a lion’s mask terminal and decorated with blossoms and foliate strapwork repeated as a border around the lower body.

Provenance: The collection of Dr. F.H. Fentener van Vlissingen (1882-1962), Utrecht, and thence by family descent through 2007; Aronson Antiquairs, Amsterdam, 2008; Dutch Private Collection

Literature: Described and illustrated in De Jonge 1947, p. 213, pl. 187; De Jonge 1970, p. 44, ill. 35; Aronson 2008, pp. 22-25, no. 12; TEFAF 2008, pp. 178-179.

Note: The two scenes of children’s games are painted after the engravings, La Fossette (See catalogue 2019) and Les Bouteilles de Savon (See catalogue 2019) by Jacques Stella (1596-1657) from Les Jeux et Plaisirs de l’Enfance, Paris 1657, pls. 14 and 8, respectively. Additionally, the putto standing to the left of the ball game is taken from the print, La Rangette, from the same source. According to the poem of La Fossette, the aim of the ‘nine holes’ ball game was to fill the center hole, but essentially it refers to the lottery of life at any age. In the 1969 facsimile, Appelbaum remarks that the game also was played as a board game, and is known in a version with the ball or marble filling all of the holes in sequence. This tender child, whose foremost goal Is filling up the center hole, Uses his brains and skill and might; But it may happen nonetheless That purely from capricious spite The ball will ruin his success. (Translation by Stanley Appelbaum in the 1969 New York facsimile) The poem underneath the soap bubbles print is a metaphorical reference to the insignificant and evanescent troubles and worries of adults: Here children scrap and suffer troubles For nothing greater than soap bubbles, As though for guineas, pounds and pence. And yet we see among adults The same ado, the same results For things of much less consequence. (Translation by Stanley Appelbaum in the 1969 New York facsimile) The Stella prints are known to have been used also on flower holders. Two examples after La Rangette and La Balançoire are illustrated by Van Aken-Fehmers 2007, p. 23, ills. 9a-b, and pp. 170-171, ills. 1a-b, cat. no. 4.11, the latter marked for Adrianus Kocx at De Grieksche A (The Greek A) factory.

Brown-Glazed Garniture, Delft, circa 1715. Marked CK in yellow, probably for Cornelis van der Kloot, a master painter at De Metaale Pot (The Metal Pot) factory from 1697. Heights: 31 to 24 cm. (12.2 and 9.4 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Comprising three covered ovoid vases and a pair of beaker vases, each with a brown ground finely decorated in yellow with scrollwork and trelliswork cartouches beneath a Greek key band around the rim, motives, the domed covers similarly decorated beneath a teardrop-shaped knop.

Provenance: The Fuld Collection, Scheveningen, until 1920; The Jacob Lierens Collection, Amsterdam, until 1949; Private collection, Lille (France), until 2002; Aronson Antiquairs, Amsterdam, 2003; Dutch Private Collection.

Literature: Described and illustrated in Frederik Muller & Cie, Amsterdam, 18-24 October 1949; Het Financieele Dagblad, March 15, 2003.

Note: Brown-ground Delft is even rarer than ‘Black Delft’, of which only about 65 pieces are known. The largest assemblage of ‘Brown Delft’ is in the Evenepoël Collection at the Musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire, Brussels, which in contrast to its extraordinary holdings of 27 pieces of ‘Black Delft’, nevertheless, has only 16 pieces of ‘Brown Delft’. The CK mark has been discussed throughout the years by various scholars; Havard 1909, vol. II, pp. 114-115 attributed it to Cornelis Aelbregtsz. (de) Keyzer (1668-1680), while De Jonge 1947, p. 222 mentions De Keyzer as working for De Twee Scheepjes (The Two Little Ships) factory, but attributes the CK mark to Cornelis Koppens, the owner of De Metaale Pot (The Metal Pot) factory from 1724 to 1761 (ibid., p. 219). It seems most likely, however, that this brown-ground garniture can be attributed to Cornelis van der Kloot, a master painter, who, according to De Jonge 1969, p. 94, transferred in 1697 from De Dissel (The Pole) factory to De Metaale Pot, then owned by Lambertus van Eenhoorn. It is no coincidence that by employing the most highly skilled artisans, De Metaale Pot was the most successful factory producing Delftware at that time, exceeding even its significant competitors: De Drie Postelyene Astonne (The Three Porcelain Ash-Barrels), De Paauw (The Peacock) and De Grieksche A (The Greek A) factories. The high quality of the present garniture, together with the fact that Cornelis van der Kloot worked among the most talented specialists at the turn of the seventeenth to the eighteenth century, leads to the reasonable conclusion that he was the maker of these rare vases.

Similar examples: A ‘Black Delft’ five-piece garniture, comparable in style and size to the present garniture, and also marked for De Metaale Pot, in the Musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire, Brussels (inv. nos. Ev. 248 a and b), is illustrated in Lahaussois 2008, p. 139, g. 8. A similar black beaker vase and baluster-shaped vase and cover, marked CK are illustrated in Dumortier 1990, no. 25 (inv. no. Ev. 270); a comparable brown-ground baluster-shaped vase with a CK mark and chinoiserie decoration is illustrated in Mariën-Dugardin 1971, no. 48 (inv. no. Ev 271), and another brown-ground vase with chinoiserie decoration was illustrated in Aronson 2017, pp. 52-53, no. 24

Pair of Polychrome Hen Tureens and Covers, Delft, circa 1765. Marked A IH 12 106 for Jacobus Halder Adriaensz., the owner of De Grieksche A (The Greek A) factory from 1764 until 1768. Heights: 11.5 cm. (4.5 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Each modeled as a hen seated in a grassy oval nest, surrounded by her white eggs, her head raised and with her wings outstretched, her plumage finely delineated in manganese, shades of green, iron-red and blue.

Provenance: Salomon Stodel Antiquités, Amsterdam, 1991; Dutch Private Collection

Literature: Described and illustrated in Lahaussois 2008, p. 184, ill. 13

Note: Zoomorphic tableware, like this pair of hen tureens, evolved from polychrome sugar or wax figures and bird-shaped pastries that decorated the Renaissance table. Especially the savory pie must have functioned as an inspiration for these tureens, which was the showpiece of the dinner table from the late medieval period and the seventeenth-century. Savory pies were stuffed with meat, fish, or poultry and were considered the highlight of a meal. Although there were simple recipes that could be made at home, pastry-cooks were hired to create the most splendid pies for special occasions. These pies were often made with large birds and were served with head, wings and upstanding tail. There were even pies which were modeled as a breeding bird, probably similar to this pair tureens with a hen amidst her eggs. Poultry was a common game hunted in the Netherlands. It was often featured as the main ingredient of many meat recipes, especially rooster and capon. Swan, heron, partridge, pheasant, dove, duck and goose were also mentioned in recipes, as well as peacock and snipe. Perhaps the most impressive dish on the table was roast swan or peacock, the grand culmination of a feast. In some cases, especially in Germany and France, complete zoomorphic services were displayed on the table amongst other tableware and trompe l’ceil objects. This type of service was reserved for festive occasions, such as the beginning of the hunting season or other hunting-related parties.

Similar examples: Although there are several tureens known from the production period of Jacobus Halder, such as tureens modeled with deer, plovers and pikes, there are only two other similar single hen tureens. One similar tureen and cover, also marked for Jacobus Halder Adriaensz. at De Grieksche A factory, is in the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague (inv. OC-D 255-1904), illustrated in Van Aken-Fehmers 1999, p. 144, ill. 51, and p. 87. Its companion piece was at Nijstad Antiquairs, Lochem, in 1952.

Pair of Polychrome Crouching Hare Tureens and Covers, Delft, circa 1765. Marked with the numerals 1, 1, 4, and 3, 3, 6 in blue on the covers. Heights: 13.5 cm. (5.3 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Each cover modeled as a hare, painted with manganese delineated facial features and fur, lying on a green oval base, the oval tureens with yellow rims painted with a band consisting of yellow flowerheads alternated by iron-red bows and blue floral sprigs.

Provenance: The collection of S. Alberge, The Hague, circa 1929, and one bearing the label Collection S. Alberge, La Haye, 14; Aronson Antiquairs, Amsterdam, circa 1980; The Vanhyfte Collection, Belgium, until 2003; Aronson Antiquairs, Amsterdam, 2003; Dutch Private Collection exhibitions ‘Tentoonstelling van Oude Kunst’ at the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, 1929.

Similar examples: Animal tureens of this model are rare. A different model of a hare tureen is in the collection of the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague (inv. no. 0400865) and another hare tureen modeled similar to the covers of the present tureens is illustrated in Aronson 2018, p. 105, no. 63.

Delftware has been a national symbol of Holland for almost 400 years. Although it was initiated by the demand for the waning importation of Oriental porcelain from the 1640s, the history of Delftware starts in fact earlier. In the first half of the fifteenth century, mercantile cities such as Bruges and Antwerp in the southern Netherlands (now Belgium) became familiar with earthenware, so-called maiolica, from southern Europe through both trade and political contacts with Italy, Spain and Portugal. Dutch Maiolica is an earthenware product coated with a tin glaze on the front or exterior and a highly translucent lead glaze on the back or base. Maiolica dishes were fired face down on three spurs that often left marks which remained visible in the central design.

By the middle of the fifteenth century, largely through the gradual migration of potters from southern Europe through France to the Netherlands, the earthenware industry had become well established in Antwerp. In the second half of the sixteenth century, under religious pressure, many of the reformists and Protestants were forced to leave Antwerp. Most moved to London, Hamburg or the northern Netherlands and specifically to the city of Haarlem (the city after which New York’s ‘Harlem’ was named) near Amsterdam.

Majolica Polychrome Plate, Haarlem, circa 1630. Diameter: 24.5 cm. (9.6 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

The center painted with an ochre and green footed bowl with foliate handles, filled with an arrangement of three ochre apples, two bunches of blue grapes and green and ochre leaves, the cavetto encircled by four concentric blue lines, and the rim painted with ochre and blue blossoms, all separated by narrow ochre panels and three blue dotted lines, the reverse lead-glazed.

Provenance: The R.J. Bois Collection, North-Holland.

Note: Early Netherlandish majolica consisted mainly of dishes and porridge bowls covered on the front in an opaque white tin glaze, and on the reverse with a less costly transparent lead glaze. Majolica can be distinguished from Delftware not only by the clear glaze on the reverse, revealing the buff-colored body of the clay, but also by the three small spots of glaze damage on the front (prunt marks). These marks were created when the pieces were stacked on top of one another in the kiln, separated by ceramic triangles that were broken away after the firing. In that process, the point where the triangles had rested left a small unglazed mark. Majolica objects were often decorated with southern European patterns, such as colorful fruits derived from Italian grotesque ornaments. This imagery appeared on ornamental tazza and on tiles produced around the same period. In fact, tiles decorated with colorful tazzas seem to have enjoyed a strong popularity.

Similar examples: Plates painted with fruit-filled tazza are not uncommon in majolica. In Aronson 2015, p. 17, no. 7 is a dish depicting a fruit-filled bowl. A similar dish in the Fries Museum, Leeuwarden, is illustrated in Lunsing Scheurleer 1984, p. 33. Another dish with a similar ‘Renaissance fruit dish’ decoration within a floral border, and dated in the center 1632, is in the Frans Hals Museum, Haarlem (inv. no. OA 91-48), illustrated by Biesboer 1997, p. 125, pl. 145. An identical example with the central pomegranate split open and ascribed a date of circa 1620-45, is in the collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam (inv. no. BK 18020), illustrated in Hudig 1929, p. 13, fig. 4.

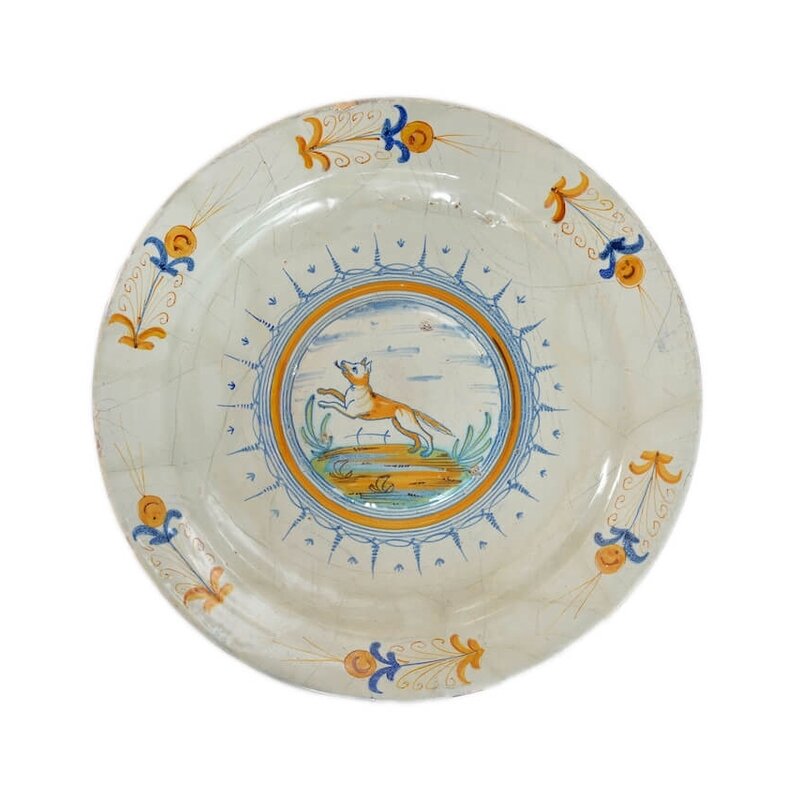

Majolica Polychrome Large Dish, Haarlem, circa 1630. Diameter: 33 cm. (13 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Painted in blue, ochre, green and manganese in the center with a fox in a landscape in a roundel of an ochre band between concentric blue lines and stylized curves, the rim painted with six stylized aigrettes, the reverse lead-glazed.

Provenance: The R.J. Bois Collection, North-Holland

Similar examples: The decoration on the edge of the plate is very similar to the one on a bowl attributed to Willem Jansz. Verstraeten, which resides in the Frans Hals Museum in Haarlem (inv. no. OA 93-131), and which is illustrated in Biesboer 1997, p. 94, no. 104. Another similar charger, but with the depiction of a deer, is illustrated in Aronson 2018, p. 11, no. 5.

Majolica Polychrome Porringer, Haarlem, circa 1625. Attributed to the workshop of Verstraeten. Diameter: 22 cm. (8.7 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

The center of the interior painted in blue with stylistic scroll motifs within a yellow band between blue concentric lines below a zigzag line, and the lead-glazed exterior affixed with two scalloped flat handles at the blue dashed yellow rim that are pierced in the center with a roundel surrounded by blue scrolls and whorls.

Provenance: The R.J. Bois Collection, North-Holland

Note: One of the most renowned Dutch families to produce wares in the maiolica (or majolica) tradition was the Verstraeten family from Haarlem, especially the father and son Willem and Gerrit. The elder Verstraeten was making the old-fashioned majolica and the son ventured into the more modern faience. Many excavated objects from Haarlem showing the same type of decoration are automatically attributed to Willem Jansz. Verstraeten, however there is still some uncertainty about their provenance because of slight differences in the decoration, molding and glazing. The present porringer however can be attributed to the Verstraeten workshop with certainty. Not only because of its stylized characteristics, but also since it was excavated in the cesspool of one of the family’s houses in the 1970s. As described by Helga Danner, “The real estate of the family Verstraeten” in Baart 2008, this house with a garden, located on the Blekerstraat, was bought by his son Gijsbert in 1655. Gijsbert, who in the same year also had bought a pottery on the Bakkenessergracht with the name De Gecroonde Keijser (The Crowned Emperor), sold in 1656 his real estate and settled in Delft. Both Willem and his sons Gerrit and Gijsbert Verstraeten belonged to the Haarlem dignitaries. They were very well-to-do, judging from the amount of real estate in their possession in the town.

Similar examples: A porringer of this size and shape, but with bird and floral decoration, is illustrated in Aronson 2010, p. 42, no. 20 and one with a cupid decoration in Aronson 2015, p. 12, no. 4. Another one with a cupid decoration and of slightly large size is illustrated in Scholten 1993, p. 95, no. 83.

The rise of the potting industry in Haarlem occurred simultaneously with the decline of the beer brewing industry in the town of Delft. As the Delft brewers ceased production at the beginning of the seventeenth century because the town’s canal water had become too polluted to be used to make a potable brew, their large abandoned buildings on the canals were quickly occupied by the pottery-makers, who could utilize both the space and the convenient water source for the working of their clays and for the transportation of their raw materials and finished wares.

At precisely the same time and throughout the seventeenth century, the Dutch developed a dominance in the European trade with China through which they imported large cargoes of luxury goods, including the much-coveted blue and white porcelain. By the middle of the century, however, a war in China interrupted the production and exportation to the Netherlands of Chinese porcelain, which declined from a quarter million pieces per year to a mere trickle. The potters in Delft seized the opportunity to fill the void, and they began producing earthenwares in emulation of Chinese porcelain, which they successfully marketed as “porcelain.”

Blue and White Small Bowl, Delft, circa 1670. Diameter: 16 cm. (6.3 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Painted around the exterior with three medallions decorated with different chinoiserie scenes of a man seated in a landscape with shrubbery and rocks, alternated by interstices pierced with a flowerhead in a roundel, all beneath two dentil bands, the cupped rim with three scale-work panels alternated by fretwork panels, the interior painted in the center with a bird and a flitting insect all in a roundel, and the sides with three medallions decorated with a fruiting plant motif.

Provenance: A Belgian Private Collection, before 1913 and thence by family descent

Similar examples: Early Dutch Delftware bowls are rare, and a bowl with pierced openwork of this early date is even more uncommon. The bowl can be attributed to a group of faience that is decorated with chinoiserie scenes of figures seated in a landscape of rock work and trees and was manufactured between 1660 and 1680. Although the majority of these objects consists of chargers and jars, there are also a few bowls in this group. A smaller bowl decorated with a continuous scene of a man seated in a landscape is in the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague (inv. no. OC(D)3-1994) and illustrated in Van Aken-Fehmers 1999, p. 234, no. 79, and another bowl with several chinoiserie scenes in a private collection in The Hague is illustrated on p. 235.

Blue and White Chinoiserie Charger, Delft, circa 1685. Diameter: 30.3 cm. (11.9 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Painted in the center with a Chinese man holding a fan and gesturing toward a low table set with a steaming large teapot and a smaller teapot, his attendant carrying a pennant and standing behind him, all within two concentric lines, the upstanding rim with four flowering plants each growing on large rock work and alternated by two birds in flight or flowering plants.

Note: This chinoiserie style charger depicts the preparation of tea using two different sizes of teapots. The large teapot functioned as a kettle to heat the water. The water was then poured into the smaller teapot that contained tea leaves. Early Chinese teapots are generally of a small size and were intended for individual use with each pot reserved for making a particular type of tea. The size reflects the importance of serving small portions each time so that the flavors can be better concentrated, controlled and then repeated. Some records suggest that the Chinese carried their teapots and drank the prepared loose leaf tea directly from the nozzle of their teapots. Although this does seem rather strange, it is also very practical. The red Chinese Yixing teapots were seasoned after repeated use, making it unnecessary to use tea leaves every time. In seventeenth-century Holland, where tea was an exotic and expensive luxury and consumed sparingly, teapots were also of a small size. As in China, teapots were used as infusion pots, and once the strong brew was poured into a cup, it would be diluted with water from a kettle.

Similar examples: A blue and white charger with a comparable scene of a two Chinese figures standing next to a table with a steaming kettle and teapot is illustrated in Aronson 2015, p. 34, no. 18.

Blue and White Garniture, Delft, circa 1690. Each marked GK in blue for Gerrit Pietersz. Kam, the owner of De Drie Posteleyne Astonne (The Three Porcelain Ash-Barrels) factory from 1673 until 1700. Heights: 13 to 21.6 cm. (5.1 to 8.5 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Comprising two ovoid jars, two bottle vases and an attenuated ovoid bottle with a flaring cylindrical neck; each painted in an Eastern style with three or four rotund teardrop-shaped panels centering a six-petal blossom surrounded by leaves on a stippled ground, alternating with similarly decorated small diamond-shaped panels issuing scrolls and ‘ribbons’ partially surrounding the larger panels, the cylindrical necks of the bottle vases similarly decorated but with two panels of each shape, and the lower body of each with blossoms alternating with triple circlets above a chevron-and-dot border repeated around the rim.

Provenance: The ovoid bottle from the collection of Dr. F. H. Fentener van Vlissingen (1882-1962), Utrecht, and thence by family descent LITERATURE The bottle was described and illustrated in De Jonge 1947, p. 211, pl. 185 & Aronson 2008, p. 37, no. 20.

Note: The design and display of garnitures follows the evolution of interior design in Europe, specifically the central role of ornamental ceramics. The fashion for grouping vases on mantels was a typical European phenomenon. With the Chinese porcelain wares, the objects were often acquired, or later commissioned, in pairs and displayed symmetrically on a mantelpiece, above a door or on a piece of furniture, such as a cabinet. At the end of the seventeenth century, the first Dutch Delftware garnitures were created, existing of three, five, seven and sometimes even more pieces. The present garniture is inspired by both Chinese and Eastern wares. Buddhist nimbus motifs are alternated by a scroll and ribbon motif that shows similarities with the long floral plant motifs that are often seen on Eastern wares. Chinese porcelain and ornamental motifs traveled through flourishing trade routes, resulting in a lasting influence on the development of Eastern art. Contacts with Mediterranean countries also stimulated cross-fertilization in the arts with Europe.

Polychrome and Gilded Large Dish, Delft, circa 1710. Diameters: 35.1 cm. (13.8 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Painted in iron-red, salmon, black and gold in the center with a Chinese man, his attendant standing behind him holding an umbrella and both walking towards a female figure graciously depicted in her flowing robes with a child in her arms, probably the Goddess Guan Yin, all in a fenced garden, the cavetto and rim decorated with large panels of flowering plants and a flitting insect.

Note: Delftware with a decoration painted only in iron-red and gold is extremely rare. The style is probably inspired by Chinese porcelain wares that were decorated only in iron-red, gold and sometimes with the addition of black enamel, which are traditionally called ‘Milk and Blood’ in the Netherlands. Interestingly, in the eighteenth century the name was also applied to a specific type of imported Indian chintz, with predominantly red decorations on a light ground. Apparently, this type of porcelain was popular mainly among the Dutch, and the very few pieces that can be found elsewhere in Europe usually come from the Netherlands. The composition and iconography conform to the normal export assortment of blue and white Kangxi porcelain of circa 1700. In contrast to the many Chinese porcelain wares in this color palette, Delftware objects painted in only iron-red and gold are rather unique. The depiction of the Goddess Guan Yin, an icon of mercy and passion also holds a strong connection to the Chinese porcelain objects. Guan Yin reached the point where she could become a Buddha (enlightenment) and yet she decided to stay on Earth, remaining a “Pu Sa”. She wanted to help humankind achieve better karma, leading them to the Western Heavens to achieve serenity and joy. Because she had the ability to comfort the sick and senile, Guan Yin was broadly admired and adored. She touched their hearts and souls, creating a sense of peace and relief amongst those who were less fortunate. Guan Yin is also often worshipped by people wanting a child and is therefore also seen as the bringer of children, hence the baby she is carrying in her arms.

Polychrome Chamfered Square Plaque, Delft, circa 1750. Height: 24.5 cm. (9.6 in.); Width: 24.8 cm. (9.8 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Painted with two Chinese men seated at a table set with food, to which one helps himself, a lady approaching with a vase at one end, and an attendant standing at the far end, the rim with a band of stylized scrolls, pierced at the top for suspension; the reverses glazed.

Provenance: According to our archives, collection Decroix, Lille, sold at Drouot Paris, 7/8 November 1919, lot 29 (illustrated); Glerum Auctioneers, 13 March 1991, lot 480; Salomon Stodel Antiquités, Amsterdam

Note: By the end of the seventeenth century, Delftware plaques were marked by their refinement and creativity of design and decoration. The shapes of the pieces, whose contours were often cut out and molded, became increasingly stylized. The varied representations on the plaques often reflected contemporary concerns and tastes. Although guild membership granted Delftware painters compositional freedom, many plaques were inspired by canvas paintings or prints, which were often made after original paintings. The present motif was probably inspired by scenes on Chinese famille verte porcelain from the Kangxi period, which the Delftware painter then placed in a typical Western stylized band.

Similar examples: A similarly decorated oval plaque, but with the figures in an interior setting, is illustrated by Lahaussois, 1994, p. 121, no. 148. A plate with the same figural decoration is illustrated in Aronson 2004, p. 126, no. 146, another larger plate is in the Evenepoël Collection, illustrated by Helbig, Vol. II, p. 108, fig. 104, and another example (see below) is in a private collection.

From the 1680s the Delftware industry has constantly innovated with new shapes, decorations and functions. Through the influence of Queen Mary, the taste for painted Delftware spread rapidly through a wealthy European elite. Because of its remarkable diversity of shapes, the delicacy of the decoration and the gaiety of its colors, Dutch Delftware became the source of inspiration for many ceramic centers throughout Europe and even Oriental potters.

Despite its predominant role in the history of European ceramics, Dutch Delftware only became a serious source of interest from art historians and collectors in the second half of the nineteenth century, a period that rehabilitated the decorative arts, and particularly ceramics. Delftware was assembled, classified and studied, and finally given its honorable recognition alongside seventeenth and eighteenth century European ceramics.

From that time onwards Delftware collections were formed, often with the advise of an art dealer. The art dealer would advise the client on objects to acquire, specifically those that would compliment their collection. In some cases, their role was to dissuade the collector from purchasing an object that did not belong in their collection. The fruits of this long relationship only became visible towards the end when the collection was nearly complete. Only when the collector, or in some cases the family, started deaccessioning it became apparent what weight the collection held.

Since 1881, over five generations of the Aronson family have brought to market the highest quality Delftware and assisted many collectors in the formation of their collection over the years. Aronson Antiquairs was founded in the city of Arnhem and is one of the oldest antique dealers in the Netherlands. Although initially they were general antiques dealers, over the past 70 years a preference for the Dutch national product arose, seventeenth and eighteenth-century Delftware. This passion has ensured that Aronson Antiquairs has specialized fully on this subject since the mid-1990s.

Many Delftware collections formed the basis for many museum collections. For example, the collections of the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the Gemeentemuseum in The Hague (soon to be Artmuseum The Hague) and Musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire in Brussels were all initially founded with private collections. This also holds true for the majority of the collections in the British Museum in London, the Louvre in Paris, the Metropolitan Museum in New York or the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, Australia amongst others.

However, as Robert Aronson explains by quoting his late grandfather, “selling or donating objects to a museum means that the object would never return to the open market.” In that light, some private collectors specifically want future generations of art collectors to enjoy the objects and the collecting as much as they did. As is the case with the present Delftware collection that will be on display at TEFAF Maastricht. “So a completed art collection does sometimes not go to a museum, but it returns to the advisors, the art dealers in this case. The collection gave tremendous pleasure to its Dutch collectors and we hope the objects will continue to spread joy for future generations.”

TEFAF Maastricht will be held from March 16 through 24 at the Maastricht Exhibition and Congress Center (MECC).

Blue and White Sugar Caster and Cover, Delft, circa 1690. Marked AK in blue for Adrianus Kocx, the owner of De Grieksche A (The Greek A) factory from 1687 until 1701. Height: 12.3 cm. (4.8 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

The cylindrical body painted on the front and reverse with flowering plants alternating with Tudor roses between trefoil bands above a border of ‘fluting’ and beneath the threaded neck, the pierced and threaded cover with a blue ground reserved with scrolls, dots and a herringbone band.

Provenance: The Dr. Günther Grethe Collection, Hamburg; Aronson Antiquairs, Amsterdam, 2004; Dutch Private Collection

Literature: Described and illustrated in Aronson 2004, p. 73, no. 86

Note: In the second half of the seventeenth century, the French influence could be felt throughout Europe. During meals, the grandeur of the French court was displayed by the largest dinner services seen at the time. This set the standard for the other royalty in Europe, and created the wish for large services consisting of plates, dishes, platters and bowls of different sizes, but with matching shapes and decorations. The Delft potters quickly took up the challenge to create the like in tin-glaze earthenware and looked around for examples to emulate in Delftware. Often, they found them in silver objects. Delftware was a wonderful medium to combine objects of silver, copper, glass, pewter and earthenware, since it could be shaped in a wide variety of forms. Among the newly desired objects of use were saltcellars, spice boxes, cruet sets, butter tubs and also sugar casters. Casters like the present were filled with sugar candy that had been finely ground in a mortar, which resulted in a coarser sugar than we are used to today.

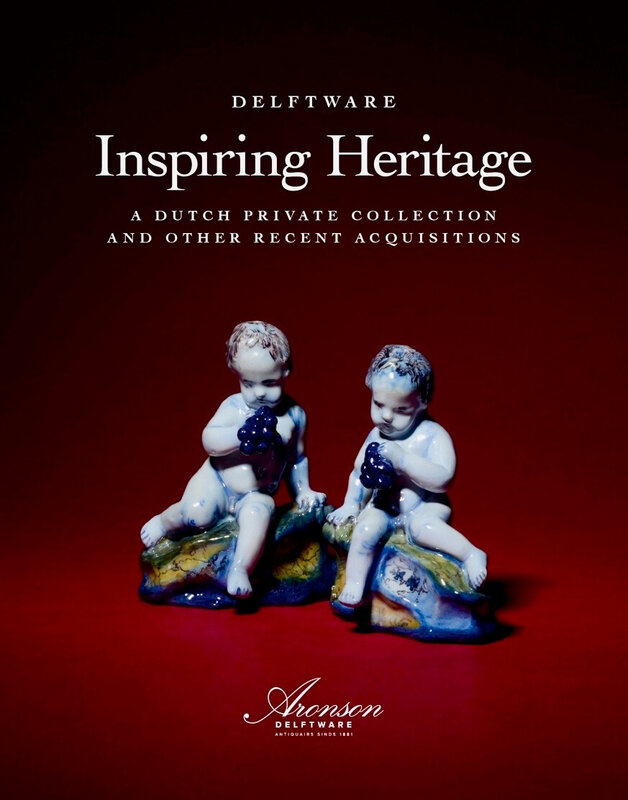

Pair of Polychrome Figures of Seated Putti with Grapes, Delft, circa 1760. Heights: 13.5 cm. (5.3 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Each putto finely delineated and accented in blue, and with manganese hair and facial features, modeled affronté, each raising toward his mouth a bunch of blue grapes held in one hand, and seated on a polychrome-marbleized shaped and sloping rockwork base.

Provenance: Salomon Stodel Antiquités, Amsterdam, 1997; Dutch Private Collection

Note: These figures probably reference the bacchanalia, a festival that honored Bacchus, the Greco-Roman god of agriculture, wine and fertility. Bacchanalia ceremonies were introduced in Italy around 300 B.C., and were originally celebrated in secrecy on the 16th and 17th of March. The celebration later became public and was celebrated in Greece, Egypt and Rome. The mythological bacchanalia theme became a popular source of inspiration for artists, including Dutch Golden Age painters and decorators who often depicted the procession of Bacchus. These processions often included bacchantes, centaurs, fauns and joyful children, which were a recurring subject. Bacchic putti were often represented while playing, dancing, drinking, or sometimes harvesting. When holding grapes, Bacchic putti can be interpreted as an allegory of autumn, the season when grapes were harvested.

Similar examples: An identical pair of white-glazed figures at the Gemeentemuseum, Arnhem, is illustrated in Vormen uit Vuur, vol. 229, 2015/3, p. 68, no. 118. A pair of the same models, but without the grapes, is illustrated in Lavino, p. 104 (upper right).

Blue and White Plate, Delft, circa 1760. Diameter: 23 cm. (9 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Painted in the center with the mythological story of Narcissus, depicting a seated Narcissus looking at his reflection in the water, with two hunting dogs and trees in the background, the rim with a floral trellis diaperwork band reserved with four panels painted with flowering plants.

Note: The classic, mythological story of Echo and Narcissus is written in book three of Ovid’s Metamorphoses. One day when Narcissus was walking in the woods, the nymph Echo saw him and fell in love with him. Narcissus sensed he was being followed and shouted “Who’s there?” upon which Echo repeated “Who’s there?”. When she eventually revealed her identity and tried to embrace him, Narcissus rejected her. She was heartbroken and spent the rest of her life in lonely glens until nothing remained of her but an echo sound. Nemesis (as an aspect of Aphrodite), the goddess of revenge decided to punish Narcissus after learning this story. The plate depicts the moment when Narcissus was getting thirsty after hunting and was lured by Nemesis to a pool. He leaned upon the water and saw himself in the bloom of youth, not realizing that it was merely his own reflection. Narcissus fell deeply in love with it and was unable to leave the allure of his image. He eventually realized that his love could not be reciprocated and he melted away from the fire of passion burning inside him, eventually turning into a gold and white flower. This myth inspired many artists and artisans, such as Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio (1571-1610), see illustration beside, and the Delftware painter who probably decorated this plate after a print.

Pair of Polychrome Birdcage Plaques, Delft, circa 1770. Heights: 30 cm. (11.8 in.); Lengths: 27 cm. (10.6 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Painted in mirror image, each with a yellow canary bird perched within a wooden cage decorated on the front with a blue and white cartouche depicting a sailing boat in a river landscape, a blue feeding cup suspended at one end, and the arched top pierced with a hole for suspension.

Provenance: Salomon Stodel Antiquités, Amsterdam; Dutch Private Collection

Note: This pair of birdcage plaques demonstrates the trompe l’ceil (deceive the eye) technique, a style often used in old master paintings to captivate and fool the viewer. The Delft potters probably took inspiration from seventeenth-century still life paintings with trompe l’ceil effects. As can be seen on this pair of plaques, the painted depth and realism of the scene create an optical illusion. Not only in trompe l’ceil paintings, but also in seventeenth-century genre paintings birdcages are often depicted.

Similar examples: Birdcage plaques of this form with minor variations are illustrated by Lahaussois 1994, p. 124, nos. 154 and 155; Lavino, p. 117 (top right); Morley-Fletcher and McIlroy 1984, p. 232, no 1; Vandekar 1978, p. 11 (top left); and Aronson 2007, pp. 70-71, no. 53.

Pair of Blue and White Rectangular Herring Dishes, Delft, circa 1770. Each marked in blue with an axe for De Porceleyne Byl (The Porcelain Axe) factory. Lengths: both 23.3 cm. (9.2 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Each painted in the center with a scaly herring within a border of leaves and scrolls on the scalloped and barbed edge of the chamfered rectangular rim.

Note: The herring, also known as ‘silver of the sea’ provided an important source of income for the Dutch fishing trade. During the first decade of the seventeenth century alone, there were approximately 770 ships (buizen) within the herring fleets. Herring fish were nutritious, inexpensive and like cod, had an extended shelf life when they were preserved in a barrel of salt Thus, the fish could be consumed all year-round. The best way to eat herring, according to the Dutch poet Jacob Westerbaen, was with onions, bread, butter and beer from Haarlem, Delft or Breda. Given the popularity of this Dutch delicacy, herring dishes became a very typical object of the Dutch kitchen in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Various types of dishes especially conceived for its tasting were produced. They were sometimes modeled as a fish, an oval, or a rectangular shape with the depiction of a herring in the center as in the present pair.

Similar examples: A single herring dish with similar border decoration and marked for De Porceleyne Byl is illustrated in Aronson 2007, p. 72, no. 54. Another similarly bordered De Porceleyne Byl herring dish is illustrated by Van Dam 2004, p. 185, fig. 133. A pair of examples by De Roos (The Rose) factory is illustrated by Van Aken-Fehmers 2001, p. 285, ill. 91; and one of those is illustrated by Jörg 1983, p. 164, ill. 119, along with its Chinese export porcelain counterpart, p. 84, ill. 39. On p. 88, the author dates the object circa 1775 based on records of herring dishes imported by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) at 42 cents apiece with one herring, or 52 cents apiece if painted with two herrings.

Polychrome Figure of a Parrot on a Ring, Delft, circa 1770. Height: 25.2 cm. (9.9 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Painted with finely and naturalistically iron-red delineated plumage on the yellow breast, wings and crest, a green back, tail and head dashed in iron-red, the beak and feet colored in blue, and modeled perched on a yellow ring with a suspension loop affixed at the top.

Provenance: C.J.J. Weegenaar Antiquair, The Hague, 1983; Dutch Private Collection

Note: Delft parrots were produced from the beginning of the seventeenth century until the end of the eighteenth century, showing their great popularity, as is discussed in Lunsingh Scheurleer 1984, p. 132. The basic form was a naturalistic rendering of a parrot, but some bird figures were modeled after the porcelain blanc de Chine hawks, illustrated in exh. cat. Blanc de Chine, 1985, p. 15, no. 19. With their strong legs, high chest and claws, they appear sturdy and serious. However, the plumage is painted with bright colors and patterns not seen in nature, making these forms beautiful ornaments for the interior. The Delftware birds were produced in several models, and are often seated on an oval base or a naturalistic pierced rock. Other examples are seated on a branch or, as the present example, in a ring that could be suspended from a higher attachment point.

Similar examples: Dutch Delft parrots perched on a ring seem to have been among the later models of this intriguing and popular bird, and their depiction in this pose also appears as the decoration on Delftware plates. According to C.J.A. Jörg and F.T. Scholten, “De Collectie Delfts aardewerk in het Groninger Museum,” Groningen 1990, in M.M.V.V.C. (1990), 140, p. 44, these models might have been intended to serve as affordable substitutes for the rare and expensive live examples. A very similar parrot is illustrated by Boyazoglu 1983, p. 74, no. 151; and Boyazoglu, de Neuville 1980, p. 257, pl. 84. Others of this general size are illustrated by Lavino, pp. 46 (bottom, center), 129 (top, left) and 147 (top, left); by Mees 1997, p. 192 (center); in Nederlandse Vereniging van Vrienden van de Ceramiek, Mededelingenblad 140, p. 44, no. 83; and in Aronson 2003, p. 58, no. 56. A larger example is illustrated by Neurdenburg, Rackham 1923, pl. L, g. 81; several smaller examples are illustrated in Schaap 2003, pp. 60-61; Aronson 2000/2001, no. 37, and Aronson 2007, pp. 56-57, no. 42.

Pair of Polychrome Models of Parrots, Delft, circa 1775. Heights: 17.5 cm. (6.8 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Each with iron-red-delineated green and white plumage on the breast and lower body, a blue back and head, and blue, green, yellow and iron-red wings, the blue feet straddling the open top of an oval base painted in blue to resemble rockwork.

Provenance: The collection of A. van Acker (1898 – 1975), the former Prime Minister of Belgium, Bruges; Aronson Antiquairs, Amsterdam, 1998; Dutch Private Collection.

Note: The exoticism of parrots have remained since the eighteenth century when the colorful birds were popularly used as models in both porcelain and pottery. Like many Delftware objects, the ceramic parrots were first inspired by Chinese porcelain wares from the Kangxi period (1662-1722). The porcelain parrots found widespread appeal in both China and Europe for their colorful and exotic appearance, the earliest pieces often in the famille verte palette. Once the figures reached the Netherlands, they found a ready group of buyers. The bird was introduced into the Delft pottery repertoire, joining the more common animal imagery of dogs, cows and horses. The varying colors and shapes of parrots provided the Delft painters with many options for ornamental decoration.

Similar examples: Parrots, as exotic in the eighteenth century as they remain today, were particularly popular in both porcelain and pottery. In Delftware the same models were made over a long period of time, the earliest based on Chinese examples with the birds perched on variously shaped mound bases, and later modeled with the birds perched on rings for suspension. Made in several sizes, two parrots of the present size on a slightly different base are illustrated by Van Aken-Fehmers 2001, pp. 295 and 341, ill. 123, who also illustrates on p. 341, g. 1, five other parrots of this type. Another similar example is illustrated by Mees 1997, p. 192 (top). A similar pair on wedge-shaped bases is illustrated in Aronson 2007, pp. 44-45, no. 32.

Polychrome Group of Two Gentlemen in a Boat, Delft, circa 1780. Length: 22.3 cm. (8.8 in.). Price on request. © Aronson Antiquairs.

Modeled as two gentlemen sitting at either end of a rowing boat painted in yellow, iron-red and manganese, one holding two large wooden oars and wearing a manganese hat, a yellow-cuffed iron-red jacket and manganese breeches, the other seated and wearing a manganese hat, yellow-cuffed iron-red jacket and manganese breeches.

Note: The Netherlands has an abundance of waterways that have served as a thriving transportation system for centuries. The rivers and canals have always played an important role in Dutch life, and this polychrome group of two gentlemen in a boat perfectly encapsulates the cultural affection. When in the second half of the eighteenth century, the orient no longer functioned as the main inspiration source, the Delft potters focused on a more Western style. The subject of daily activities became the starting point for their ceramic wares: changes in interior design, eating habits, new fashion. Possibly following the German porcelain industry, which had set trends in the third quarter of the eighteenth century with the production of figurines, the Delft potters also made large numbers of imaginative figures and figurines in varying sizes around this period. Many of these objects were made to be displayed in glass cabinets or on etageres. Polychrome figural groups sitting in a boat are rather rare. Their rarity can be explained by the elaborate and expensive production process of these detailed objects. The smaller and more fragile details of this boat, such as the rowers and possibly the oars, were made in separate molds and added later. Whereas the larger European porcelain factories employed full-time designers to make the molds, the designs for these boats were probably created by the Delft potters themselves. The design may have been derived from porcelain examples, however no similar porcelain boats are known. Thus, it is more likely they originated from the Delft potter’s creativity. These brightly colored Delft objects found a ready market in the Netherlands, customers for whom German porcelain was too expensive or perhaps too refined. A number of factories must have been producing an enormous output. However, due to the elaborate and expensive production of these detailed objects, it must have been already costly at the end of the eighteenth century.

Similar examples: Although Delft potteries produced many miniature replicas of everyday objects, polychrome figural groups sitting in a boat are rather rare. Only eight other single groups of figures seated in a boat are known. A similar single group, in the collection of the Museum Prinsenhof, Delft (inv. no. PDA 39) is illustrated in Kievit and Klüver 2015, p. 171. Another example is illustrated in Lavino p. 146. Two other groups of the same model were sold at Sotheby’s Mak van Waay in 1967, October 31st, lot 1363 and at Sotheby’s in 1960, September 2nd, lot 34, at Glerum in 1995, June, 20th, lot 1048. Another very similar group of the same model was formely in the collection of Nelson and Happy Rockefeller. Another type of boat transporting cheese or butter is illustrated in Aronson 2003, p. 52, no. 50. A similar model was sold in Frederik Muller & Cie, 1958, lot 388. Another example is in the collection of the Rijksmuseum Twenthe (inv. no. BR0001 [R230]).

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240416%2Fob_2a8420_437713933-1652609748842371-16764302136.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_83ee65_2024-nyr-22642-0954-000-a-blue-and-whi.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_15808c_2024-nyr-22642-0953-000-a-blue-and-whi.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_e54295_2024-nyr-22642-0952-000-a-rare-blue-an.jpg)