Sotheby's announces highlights included in the Asia Week Sales Series in New York

NEW YORK, NY.- Sotheby’s unveiled the contents of its upcoming Asia Week sale series in New York. Coinciding with the 10th anniversary of Asia Week New York, the sales feature an exceptional group of over 1,150 lots spanning centuries of artistic production. All eight auctions in the series open for public exhibition in Sotheby’s New York galleries beginning 14 March, with auctions taking place from 18 – 23 March.

Christina Prescott Walker, Senior Vice President & Division Director of Asian Art, commented: “We are pleased to offer a wide range of high-quality Asian Art once again this season, at price points from $500 to over $1,000,000 and ranging from Contemporary to Ancient in date. A large number of the works offered have exceptional provenance, and many appear on the market for the first time in a generation.”

MODERN & CONTEMPORARY SOUTH ASIAN ART

Auction 18 March @ 11:00AM

The Asia Week series opens with our auction of Modern & Contemporary South Asian Art. Highlighted by a spectacular array of art by some of the most important and avant-garde artists from India, the sale is highlighted by F.N. Souza’s Golgotha in Goa – a rare work painted in Bombay in 1948 and included in the artist’s fourth solo show at the Bombay Art Society that year, which demonstrates the profound influence of Catholicism on Souza’s personal and artistic development (estimate $250/350,000). While Souza was an incredibly prolific artist across his nearly-seven-decade career, works from this formative period remain incredibly rare – less than 20 paintings by Souza from the 1940s have ever appeared at auction, marking this as a major event in the artist's market. The work remained in the artist’s personal collection until just a few years prior to his passing, and was acquired by a fellow Goan private collector who cherished it as long as he lived.

Further auction highlights include several early Maqbool Fida Husain paintings from his Japan and Banaras series, as well as iconic works by Jagdish Swaminathan, Sayed Haider Raza and Ram Kumar. The auction also features a diverse selection from the Bengal School of Art, as well as Pakistani contemporary art.

Francis Newton Souza, Golgotha in Goa. Oil on plywood. Signed, titled and dated 'F.N. SOUZA / Golgota in Goa (sic), 1948' on reverse. Bearing distressed label with 'Date of Painting 1948 / ... Exhibit II / ... Medal if previously won No! / ... (Title) of Picture GOLGOTA IN GOA ((sic) / 400 / ... Artists Francis Newton SOUZA / Name & Address 174 Carnac Rd. / Crawford Market' on reverse, 35 ½ x 35 ⅜ in. (90.1 x 89.8 cm.) Painted in 1948. Estimate $250/350,000. Courtesy Sotheby's.

JUNKUNC: ARTS OF ANCIENT CHINA

Auction 19 March @ 10:00 AM

The week continues with an exceptional selection of Chinese gilt-bronzes, weapons, jade animals, Buddhist sculpture and pottery collected by Stephen Junkunc III. The works span China’s antiquity, dating from the Neolithic to the Ming Dynasty periods, offering a fascinating insight in the rituals, religions and politics of the times.

At its height in the mid-20th century, the Junkunc Collection numbered over 2,000 examples of exceptional Chinese porcelain – once including two examples of the fabled Ru ware – jade, bronzes, paintings and Buddhist sculptures. The collection serves as a testament to a period of unprecedented abundance of important Chinese material available in the West, as well as Junkunc's limitless intellectual curiosity, coupled with the means and savvy to acquire internationally from the leading dealers in the field.

Many rare works highlight the 19 March auction, including an Exceptional Gilt-Bronze Dragon that belongs to a small number of free-standing sculptures produced during the Six Dynasties period (estimate $100/150,000). Striking for its powerful dynamism and slender elegance, the dragon, beyond its well-documented associations with the heavens and as a symbol of the emperor, also represented one of the four cardinal directions (the Green Dragon of the East). An Exceptionally Rare and Important Archaic Bronze Ceremonial Halberd Blade (GE) from the Eastern Zhou Dynasty, Early Spring and Autumn Period (estimate $200/300,000) also highlights the sale. This bronze halberd blade bears an important twenty-character inscription that reveals the name of its original owner Qu Shutuo of Chu. Twentieth century scholars, using only published ink rubbings and drawings of the present halberd, have attempted to match Qu Shutuo to members of the Qu family recorded in historical texts. The reemergence of the Chu Qu Shutuo Ge provides a great opportunity for the advancement of scholarship, as the inscription raises fascinating new questions in understanding the true identity of its original owner and the historical context surrounding him.

Lot 116. An exceptional gilt-bronze dragon, Six Dynasties (220-589). Length 5 in., 12.7 cm. Estimate 100,000 — 150,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

Cf. my post: An exceptional gilt-bronze dragon, Six Dynasties (220-589)

Lot 111. An exceptionally rare and important archaic bronze ceremonial halberd blade (ge), Eastern Zhou dynasty, early Spring and Autumn period. Length 11 1/2 in., 29.1 cm. Estimate 200,000 — 300,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

THE ROBERT YOUNGMAN COLLECTION OF CHINESE JADE

Auction 19 March 2019 @ 11:00AM

Sotheby’s will present jades from the private collection of Robert Youngman in dedicated auctions in both New York and Hong Kong this spring. The sales kick off in March with a sale offering more than 70 jades from the collection across 4,000 years of Chinese art, from the Neolithic to Qing dynasty.

A menagerie of jade animals and figures spanning from 1200 – 1800 AD will highlight the sale, featuring: a Ming Dynasty Yellow and Russet Jade Figure of Zhou Yanzi, a carving depicting the Confucian parable of Zhou Yanzi, a boy who bravely cloaked himself in deerskin among a herd of does to collect milk to reverse his elderly parents’ blindness (estimate $40/60,000); a White and Gray Jade Carving of a Hare, which embodies the Song dynasty approach of essentialist carving in which the fundamental nature of the animal is conveyed through its body language alone and stripped of superfluous detail (estimate $30/50,000); and a rare Song-Ming Dynasty Yellow and Russet Jade Carving of a Tapir, known for its mythical properties believed to eat nightmares in East Asian legends (estimate $80/120,000). Jade carvings of tapirs are exceptionally rare, and within this small group, the present carving was produced particularly early and bears atypical physical features and exceptional quality of stone and carving.

Lot 241. A Yellow and Russet Jade Figure of Zhou Yanzi, Ming dynasty(1368-1644). Height 3 1/8 in., 7.9 cm. Estimate 40,000 — 60,000 USD. Lot sold 150,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

kneeling in a loose robe with the proper left knee raised and the right knee bent to the ground, the right arm descending and grasping the handle of a milk pail, the left arm bent at the elbow with the hand clutching the hoof of a deer, the skin of the animal cloaking the back of the figure, the deer's head perched atop the boy's cap, the stone a creamy yellow tone at the front where the figure is carved, transmuting to rich brown tones at the back where the deerskin is represented, wood stand (2).

Provenance: Purchased in Hong Kong, 1964.

Literature: Robert P. Youngman, The Youngman Collection of Chinese Jades from Neolithic to Qing, Chicago, 2008, pl. 181.

The present carving identifies Yanzi with his usual attributes: the milk pail and the deerskin. From the reverse, only the animal's body can be seen, alluding to the efficacy of his disguise and Yanzi's success in completing his mission. In addition to capturing the essential features of the story in this succinct carving, the artisan has also made excellent use of the inherent qualities of the stone. The luminous yellow sections of the jade highlight the hero, while the naturally dark 'skin' of the stone maps onto the hide of the deer both distinguishing it from the figure and contributing a realistic coloration to the animal's coat.

A Song dynasty celadon and russet jade carving of this subject, from the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Henry N. Foster, was included in Chinese Jade: The Image from Within, Pacific Asia Museum, Pasadena, 1986, cat. no. 82a; a Ming dynasty version in white and russet jade is in the collection of the Freer Sackler Galleries, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D. C., acc. no. S1987.759; a white jade iteration attributed to the Ming dynasty was included in Chinese Jade: An Important Private Collection, Spink & Son, London, 1991, cat. no. 120; a white and brown jade carving of this subject from the Qing dynasty was sold in our Paris rooms, 10th June 2014, lot 35; and a 17th century celadon and russet jade example sold in these rooms, 17th September 2003, lot 128.

Lot 245. A White and Gray Jade Carving of a Hare, Song dynasty (960-1279); Length 1 3/4 in., 4.4 cm. Estimate 30,000 — 50,000 USD. Unsold. Courtesy Sotheby's.

carved seated on its back haunches, the feet tucked under the rounded body, the head turning backwards and nestling onto the left shoulder, the face in an expression of intense focus with the eyes wide open and accentuated by the ridge of the furrowed forehead, the ears folded back, the stone of a creamy tone with milky inclusions, shifting to a soft brownish-gray at the hare's back and right side.

Provenance: Mu-Fei Collection (Collection of Professor Cheng Te-K'un).

Bluett & Sons, Ltd., London, 22nd November 1990.

Exhibited: Chinese Jades from the Mu-Fei Collection, Bluett & Sons, London, 1990, cat no. 66.

Literature: Robert P. Youngman, The Youngman Collection of Chinese Jades from Neolithic to Qing, Chicago, 2008, pl. 123.

Song dynasty jade carvings of animals executed in this manner of representation include a figure of a camel-like mythical beast in the collection of the Palace Museum, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Jadeware, vol. 2, Hong Kong, 1995, pl. 58; a carving of a 'sanyang' group from the Chang Shuo Studio Collection exhibited in Chinese Jade Animals, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1996, cat. no. 90, and later sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 5th April 2017, lot 3321; a single jade ram included in the same exhibition, ibid., cat. no. 91; and white jade carving of a ram in the collection of Brian McElney, included in Chinese Jade Carving, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1983, cat. no. 142.

Lot 223. A Yellow and Russet Jade Carving of a Tapir, Song-Ming Dynasty (960-1644). Length 3 3/4 in., 9.5 cm. Estimate 80,000 — 120,000 USD. Unsold. Courtesy Sotheby's.

in a recumbent pose, with the body curving slightly to the right in a subtle arc, the legs folded to either side of the torso, the lifted head set with short triangular ears and a ridged snout curling under at the end, the gaze directed ahead, the thick round tail dangling languidly at the opposite end of the body, the hooves and the ribs neatly incised, swirling wisps of qi emanating in raised bands from the shoulders and hips, the stone a pale yellow with icy inclusions at one side of the body and a variegated russet at the other side.

Provenance: Christie's London, 31st March 1969, lot 133.

Literature: Robert P. Youngman, The Youngman Collection of Chinese Jades from Neolithic to Qing, Chicago, 2008, pl. 109.

Jade carvings of tapirs are exceptionally rare. Even within this small group, the present carving was produced particularly early and bears atypical physical features. Other jade 'tapirs' date to the Qing dynasty and closely follow the visual formula of the ancient bronze models. See for example, an 18th century white jade 'tapir' vessel, from the collection of Lolo Sarnoff, sold in these rooms, 17th-18th March 2015, lot 323; and an 18th/19th century white jade 'tapir' sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 8th April 2013, lot 3203. By contrast, the present carving dates several centuries earlier to the Song - Yuan period, and the animal's anatomy brings greater attention to the tapir's natural relationship to the horse, particularly in the long slender legs and hooved feet. Thus, the artisan's selection of this particular subject and decision to emphasize alternative physical characteristics testify to the high degree of original thought that went into making this figure.

The quality of the stone and the carving are also noteworthy. The yellow, russet, and dark brown variegation of the jade beautifully imitate the types of patterning that naturally occur on a tapir's hide. Additionally, the movement of the dark brown veining contributes to the sense of vitality of the animal. Together, these show the care with which the artisan matched the subject to the innate properties of the material.

The gentle contouring of the form and the attention to details - such as the subtle suggestion of the ribs where the body bends, and the sinuous curve of the spine that enhances the sense of the corporeal weight at rest - are consistent with the best animal-form carvings of the Song - Yuan period. Compare a strikingly similar yellow and brown jade figure of a hound, attributed to the Tang - Song period, and exhibited in Chinese Jade Animals, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1996, cat. no. 75; a Song dynasty white and russet jade carving of a horse from the Gerald Godfrey Collection, sold at Christie's Hong Kong, 30th October 1995, lot 845; a Song dynasty yellow and russet jade carving of a hound, from the Muwen Tang Collection, sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 1st December 2016, lot 200; a Song dynasty gray jade carving of a hound, from the W. P. Chung Collection, exhibited in Chinese Jade Carving, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1983, cat. no. 136; and a Yuan dynasty pale celadon jade carving excavated in Shanghai and published in Zhongguo chutu yuqi quanji/The Complete Collection of Jades Unearthed in China, vol. 7, Beijing, 2005, cat. no. 216.

KANGXI: THE JIE RUI TANG COLLECTION, PART II

Auction 19 March @ 2:00PM

Following the success of KANGXI: The Jie Rui Tang Collection in March 2018, we are pleased to present another selection of Kangxi-era ceramics from the Collection of Jeffrey P. Stamen. Built over a 30-year period, the Jie Rui Tang collection is one of the finest, most comprehensive assemblages of Kangxi porcelain in private hands.

This upcoming sale features examples of major ceramic categories representative of the period, led by The Fonthill ‘Phoenix’ Vase, a Magnificent and Rare Rose-Verte Rouleau Vase from the Qing Dynasty, Kangxi Period (estimate $300/500,000). The vase previously belonged to famous Victorian era collector Alfred Morrison, who designed his Fonthill estate to display his impressive collection of Chinese porcelains, including the present piece. Only one other similar vase of this form, massive size and distinctive palette is known, sold in our April 2017 Hong Kong auction.

Lot 343. The Fonthill ‘Phoenix’ Vase, a Magnificent and Rare Rose-Verte Rouleau Vase, Qing Dynasty, Kangxi Period (1662-1722). Height 29 5/8 in., 75.2 cm. Estimate 300,000 — 500,000. Unsold. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the tall, cylindrical body rising to a waisted neck surmounted by a galleried rim, superbly enameled in exquisitely modulated tones of blue, green, pink, yellow, aubergine, iron red, white and black, with a rich, varied and lively scene centering on an elegant phoenix poised atop rockwork, the pink-and yellow-breasted bird trailing long, flowing bluish-green tail feathers, the keen-eyed yellow head, above a slender, fully-plumed, sinuous neck, gazing at a large densely-petaled pink peony flower issuing from a green, leafy stem arching slightly under the weight of the heavy blossom, another ample bloom in blue to one side, all amid a colorful, bustling array of varying birds including ducks, peacocks, cranes, herons, and orioles and further flowers such as lotus, hydrangea and magnolia, set below a band of floral meander on a green-stippled ground enclosing alternating reserves of crab and fish along the shoulder, the neck with a slender border of pink carp leaping among swirling green waves below lush chrysanthemum blooms emerging from rockwork amid further flowering plants with a butterfly fluttering overhead and a pair of crickets perched on leaves, the base white-glazed, coll. no. 1395.

Provenance: Collection of Alfred Morrison (1821-1897), Fonthill House, Tisbury, Wiltshire.

Collection of John Granville Morrison, the Rt. Hon. The Lord Margadale of Islay, T.D., J.P., D.L. (1906-1996).

Christie’s London, 4th May 1970, lot 23.

Sotheby's Hong Kong, 16th May 1977, lot 216.

Sotheby's Monaco, 22nd June 1987, lot 1465.

American Private Collection.

Ralph M. Chait Galleries, New York, 2004.

Literature: Jeffrey P. Stamen, Cynthia Volk with Yibin Ni, A Culture Revealed, Kangxi-Era Chinese Porcelain from the Jie Rui Tang Collection, Bruges, 2017, cat. no. 56.

Celestial Emissary: The Fonthill ‘Phoenix’ Vase

This magnificent rouleau vase exemplifies the extraordinary results derived from a series of technical developments achieved towards the end of the Kangxi period. Its impressive size and striking decoration testify to the advances in porcelain production that occurred under the aegis of a progressive emperor who encouraged innovation and progress from the workers in the imperial workshops in Beijing and Jingdezhen. The present vase is one of the earliest examples of the successful and visually effective inclusion of pink and blended-color enamels within a famille-verte context.

The generous application of pink enamel and blended colors alongside a traditional famille-verte palette indicates that this piece was made in the late Kangxi period, when the relatively immutable palette of contrasting colors was gradually replaced by the more versatile famille-rose enamels, hence the term rose-verte. Numerous scholars have discussed the origins and far-reaching consequences of the introduction of pink enamel, which, together with the development of opaque white and opaque yellow, dramatically changed the look of the porcelain and considerably widened the scope of possibilities at Jingdezhen. Nigel Wood, who examined in depth the chemical composition of these porcelain colors, suggests that while the white and yellow enamels probably derived from enamels used on cloisonné ware, pink enamel was probably introduced in China from Europe through Jesuit missionaries (see Nigel Wood, Chinese Glazes, Hong Kong, 1999, pp. 241-243). This short-lived period of cooperation between imperial artists and artisans and European Jesuits inside the Forbidden City, under the watchful eye of the Kangxi emperor, was a boon for China’s material arts that brought about technical and aesthetic changes unimaginable just decades earlier. Enamels sent from Europe or custom-made at the imperial glass factory in Beijing provided a range of hues very different from the wucai or famille-verte palette in use at the same time at Jingdezhen. The European introduction of gold-ruby enamel, a transparent, deep purplish-red color derived from colloidal gold; and the impasto use of a white enamel derived from lead-arsenate, that had been made in the glass workshops for some time, for use on cloisonné enamel wares, but only now was found to be highly effective on porcelains where, mixed with other enamels, it added a whole new range of opaque, pastel tones.

The subject on this piece is notable for its auspicious meaning. As the phoenix is the king of birds, the subject of phoenix surrounded by many birds is known as ‘hundred birds courting the phoenix’ (bainiaochaohuang or bainiaochaofeng). Since the phoenix only appears during peaceful reigns, it is closely connected with the ruler, and this motif stands for the relationship between a ruler and his officials. The birds depicted in such scenes carry symbolic meaning and represent the ‘Picture of the Five Relationships’ (luxutu, wuluntu): the cranes represent the relationship between father and son; mandarin ducks, the relationship between husband and wife; wagtails, the relationship between brothers; and the relationship between friends is represented by the orioles.

Only one other similar vase of this form, massive size and distinctive palette is known, formerly in the collection of the Santa Barbara Museum of Art, Santa Barbara, California, sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 5th April 2017, lot 1116 (fig. 1). Compare also a vase of similar size and shape and painted with birds and flowers, but in the famille-verte palette with underglaze blue in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, illustrated in Suzanne G. Valenstein, A Handbook of Chinese Ceramics, Boston, 1975, pl. 131. A pair of the same type but decorated in a wucai palette, sold twice at Christie’s London, 4th May 1970, lot 23, and 9th July 1985, lot 202, and is now in the Jie Rui Tang Collection, illustrated in Jeffrey P. Stamen, Cynthia Volk with Yibin Ni, A Culture Revealed, Kangxi-Era Chinese Porcelain from the Jie Rui Tang Collection, Bruges, 2017, cat. no. 54. A related vase with bird and flower decoration sold in our Monaco rooms, 29th February 1992, lot 440. Another superbly enameled famille-verte vase of the same massive size but with figural decoration from the Jie Rui Tang Collection sold in these rooms, 20th March, 2018 lot 322.

A monumental and rare rose-verte 'birds' rouleau vase, Qing dynasty, Kangxi period (1662-1722), 74.7 cm, 29 3/8 in. Sold for 4,900,000 HKD at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 5th April 2017, lot 1116. Photo: Sotheby's.

Cf. my post: A monumental and rare rose-verte 'birds' rouleau vase, Qing dynasty, Kangxi period (1662-1722)

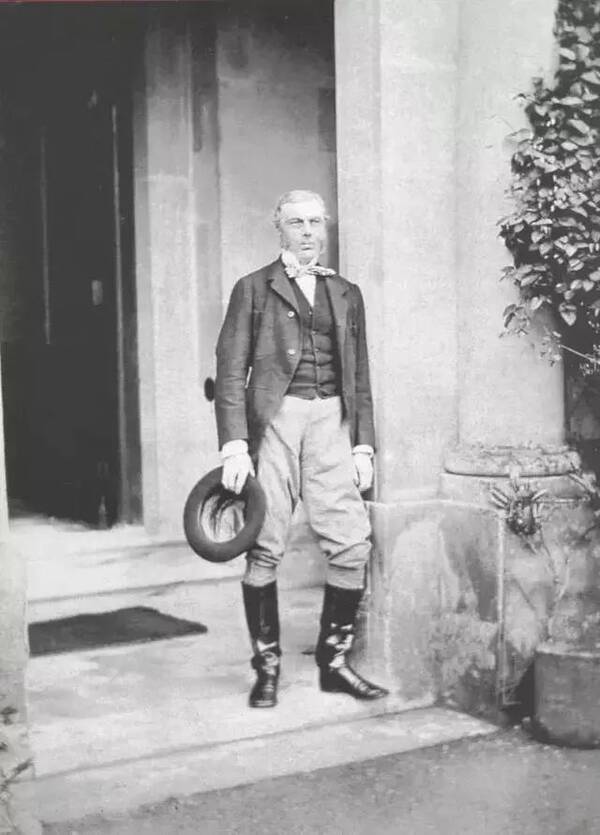

The present vase belonged to one of the most famous collectors of the Victorian era. Alfred Morrison (1821–1897) (fig.2) was the second son of the wealthy textile merchant James Morrison, who was believed to be the wealthiest ‘commoner’ in 19th century England. James Morrison gifted the Fonthill estate in the Wiltshire countryside to Alfred in 1848 and, after his father's death in 1857, he devoted much of his inheritance to collecting extraordinary art works. In the 1860s, Alfred hired one of the foremost architects of the time, Owen Jones, to design three bespoke galleries to accommodate his large collection of European paintings and Chinese decorative art. One of the grandest of these was a room done ‘in Cinquecento style’ lined with elaborate ebony and ivory cabinets to display Morrison’s impressive collection of Chinese porcelains, among which was the present vase.

IMPORTANT CHINESE ART

Auction 20 March @ 10:00AM

The Important Chinese Art auction features nearly 300 works dating from the Neolithic to Republic periods and comprising all major collecting categories – notably early bronzes, Buddhist sculpture, ceramics, imperial porcelain, jades and classical furniture. The selection is highlighted by an Exceedingly Rare and Important Complete Set of the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment by the Qianlong Emperor, Dated Qianlong Bingyin Year, Corresponding to 1746 (estimate $300/500,000). Every detail in the production of this Sutra reflects the supremacy of imperial quality, executed to the highest standards overall. The Lotus Sutra is known to have been copied by the Qianlong Emperor to celebrate the birthday of his mother, the Empress Dowager Chongqing. The present Sutra also has a long collecting history in the West, that can be traced to Bernard Alfred Quaritch, a German bookseller who opened a bookshop in London in 1847 specializing in old and rare books, which still exists today.

Lot 548. An exceedingly rare and important complete set of the Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment, by the Qianlong emperor, dated Qianlong bingyin year, corresponding to 1746. Length of each 8 1/8 in., 21.5 cm; Width 3 7/8 in., 9.8 cm. Estimate 300,000 — 500,000 USD. Lot sold 2,660,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

comprising two volumes of leporello albums, sumptuously bound in gilt-wrapped-thread brocade woven with multi-colored diaper patterns enclosing hexagonal reserves of sinuous dragons each in pursuit of a 'flaming pearl' alternating with wan and shou characters, centered with a black title slip with a gilt inscription reading yushu yuanjuejing shangce and xiace (Imperially written Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment, volume one and volume two), each album inscribed in regular script executed in black ink on dyed paper beginning with the full name of the sutra and attributing the translation to Buddhatrāta of Jibin, continuing into a neat structure of four columns of text per leaf, the first album with a frontispiece finely painted in baimiao style with the Buddha holding a blossoming lotus spray, an imperial seal reading qinwen zhixi ('seal of imperially-written text') following the name of the sutra, the second album text closing with an inscription translating to 'Qianlong commenced writing on the nineteenth day of the first month of the bingyin year and concluded on the fifteenth day of the second month', followed by three seals reading qian, long, and jigu youwen zhixi('respect tradition and value classical literature'), with a further illustration of the guardian king Weituo, all between illustrations of the 'Eight Buddhist Emblems' painted in gilt on indigo-dyed paper to the interiors of the covers, both albums fitted in a matching brocade-bound hard board case with stained ivory tabs and a title slip inset to the top (3)

Provenance: Bernard Quaritch Ltd., London.

Collection of Henry Yates Thompson (1838-1928), acquired from the above in 1882.

Collection of James R. Herbert Boone (1899-1983).

Sotheby’s New York, 19th October 1988, lot 23.

Buddhist Devotion from the Imperial Brush

Regina Krahl

The Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1795) was not the first Manchu ruler to actively support Tantric Buddhism. Connections between the Manchu ruling house and the Dalai Lama predated the Manchu conquest of China. Once on the throne, the Qing (1644-1911) emperors eagerly promoted good relations to the Lamaist clergy, since support of this Tibetan-Mongolian brand of Buddhism was considered politically advantageous, if not imperative, in order to win the allegiance of Tibetans and Mongols. The Manchu emperors thus made visits to holy sites of Lamaism and invited the Dalai Lama and other important Buddhist dignitaries to the court in Beijing, they supported Buddhist building projects in and around the imperial palaces, but also in the country at large, and initiated Buddhist publishing and printing projects. They also collected ancient imperially sponsored Sutras, and commissioned replacements of lost copies in order to assemble complete canons of Buddhist texts.

Even in this already Buddhist-friendly climate, the Qianlong Emperor’s engagement in Buddhist causes still represented an exception. As a true believer and a genuine practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism, this patronage was for him far more than a political necessity. Being considered an incarnate Tibetan Buddhist Lama, he had himself repeatedly painted in thangkaformat as on incarnation of the Bodhisattva Manjushri, from whose name the word Manchu is believed to be derived. He supported Chinese Buddhist monasteries in general, but focused personally as well as politically on Tibetan Buddhism (fig. 1). He patronized the construction of many monasteries of the Gelugpa sect, where he personally wrote lintel inscriptions and foundation tablets. Ancient Sutras in his collection – like ancient paintings and calligraphies – were impressed with his seals.

The Qianlong Emperor as Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Wisdom. Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.; Purchase—Charles Lang Freer Endowment and funds provided by a anonymous donor, F2000.4.

It was therefore only natural that he would be copying Buddhist Sutras himself, an act considered a meritorious deed, a way to accumulate blessings for one’s ancestors as well as for oneself, and in the case of an emperor, for the realm of the empire as a whole. His polished calligraphic style that he diligently practiced, gave him the tool to produce a superb work of art also from an aesthetic point of view. As the inscription at the end of the second volume tells us, he worked for nearly a month on the copying of this Sutra. Lavishly executed prototypes had been produced to imperial order at least since the Yongle reign (1403-1424) of the preceding Ming dynasty (1368-1644), several of which were in the Qianlong period preserved in the imperial library; see the discussion of the volumes of the Sutra of Perfection of Wisdom of the Xuande period (1426-1435), sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 3rd April 2018, lot 101.

Buddhist Sutras are canonical scriptures that render the teachings of the Buddha, which were brought over from India and then translated in China. The Sutra of Perfect Enlightenment, also known as the Great Vaipulya (Corrective & Expansive) Sutra on the Perfect Enlightenment was a very popular and highly influential scripture, although uncertainties exist concerning its origin.

Tang dynasty (618-907) texts list Buddhatrāta of Jibin (Kashmir) as the translator of the text, and as such he is also recorded in the present volumes. Buddhatrāta is generally considered to have been an Indian monk, who in the Tang dynasty brought Buddhist scriptures to China and translated them. One text even gives the exact date in the year 693, when he was supposed to have completed this translation in the White Horse Temple of Luoyang. Doubts about the text’s authenticity were, however, already raised in the early eighth century, and it is now largely believed to be an early text of Chinese origin. Peter N. Gregory (Tsung-Mi and the Sinification of Buddhism, Honolulu, 2002 [1991], pp. 54ff.) concludes that this Sutra was current in Chan circles in or around Luoyang during the reign of the Empress Wu (r. 690-705) and considers it one of the apocryphal texts that played an important role in the adaptation of Indian Buddhist concepts into the Chinese cultural horizon, and thus a significant work for the sinification of the Buddhist doctrine. It was particularly influential for Chan Buddhism and Zongmi (780-841), fifth patriarch of the Huayan and Chan schools and one of the towering figures of Tang dynasty Buddhism, elevated it even above the revered Huayan Sutra: “If you want to propagate the truth, single out its quintessence, and thoroughly penetrate the ultimate meaning, do not revere the Hua-yen Sūtra above all others … its principles become so confused within its voluminous size that beginners become distraught and have difficulty entering into it … It is not as good as this scripture, whose single fascicle can be entered immediately” (quoted after Gregory, p. 54).

Being an imperially sponsored book project, the present work was, naturally, executed to the highest standards overall. The elegant calligraphy of the Qianlong Emperor is impeccably executed, the characters superbly balanced on the yellow paper. The illustrations of the Buddha and Weituo are sensitively rendered in an unusual half-length format that serves to make them appear bigger. The books are opening with the depiction of the Buddha in voluminous robes, his expression compassionate and two fingers of his right hand holding a lotus flower at the height of his ear, as a symbol of the transmission of Buddha’s teachings; while a portrait of the celestial guardian deity Weituo, or Skanda, carrying a sword, is typically placed at the end of the Sutra as he is revered as protector of the Buddha’s teachings, his face expressing steadfast determination. A Tibetan prayer om ah hum is inscribed in cinnabar on the reverse side of each drawing, signifying that the sutra was consecrated. The ‘Eight Buddhist Emblems’, each supported on an elaborate baroque lotus arrangement adorned with ribbons, reflect the exuberant love of ornamentation characteristic of any work of art done to imperial order during the Qianlong reign.

Every detail in the production of this Sutra reflects the supremacy of imperial quality. The dyed-paper used for writing was made in the imperial workshops to imitate the highly precious paper, Jinsushan cangjingzhi (sutra paper from the Jinsu mountain), commissioned by the Jinsu Temple in Zhejiang province during the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127). Forty-two sheets of such paper were used for this sutra, each neatly folded into leaves of identical size and then meticulously glued together. The sheets are not all of the same length however, and therefore, the total number of leaves they can be folded into varies, from one to nine. But careful calculation and coordination ensured no single sheet was folded into more than nine leaves, as the number ‘nine’, according to ancient Chinese philosophy, represents the highest numeral and was associated with the Emperor. A small imperial yellow label, adhered to the top left corner of one of the sheets, is found on the reverse side of each volume. One label is inscribed with the Chinese character for ‘nine’ and the other with ‘five’. Each number, interestingly, corresponds to the total number of leaves within the sheet. Columns were also prepared on the paper to guide the emperor in writing. Each spread was made with nine equally spaced columns, which were produced not just with the aid of rulers, but also minutely positioned pin holes. Barely visible to the naked eyes, four minutely positioned pin holes were first pierced to define the corners, and pairs of equally spaced pin holes mark the vertical columns, all of which were then connected by faintly-drawn lines.

No expense was spared when it came to the binding and encasing of the two volumes, for which a superb gold-ground brocade with multi-colored five-clawed dragons and longevity wishes was chosen, together with red-stained ivory tags carved with dragon motifs. In addition to the present lot, at least one other copy of this Sutra written by the Qianlong Emperor is recorded, which also has two volumes, dated by inscription to 1756, catalogued in Midian zhulin xubian [Pearl forest in the secret hall: series two], published in Midian zhulin Shiqu baoji hebian [Pearl forest in the secret hall and precious collection of the Stone Canal Pavilion], vol. 3, Shanghai, 2011, p. 29 (bottom).

At least two other Sutras copied by the Qianlong Emperor are published, which were bound in the same imperial brocade and fitted with the same kind of title slips: a copy of the Lotus Sutra preserved in the Palace Museum, Beijing, copied in 1765, and a copy of the Heart Sutra, copied in 1768, with very similar illustrations and equally bearing the Emperor’s seals, preserved in the National Palace Museum, Taipei; for the former see the exhibition catalogue The Imperial Packing Art of the Qing Dynasty, The Palace Museum, Beijing, 2000, no. 80, or The Imperial Packing Art of Qing Dynasty. Classics of Forbidden City, Beijing, 2007, pp. 134-5; the latter was included in the exhibition The All Complete Qianlong: The Aesthetic Tastes of the Qing Emperor Gaozong, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 2013, cat. no. I-2.5 (figs 2 & 3).

Album of Heart Sutra by the Qianlong Emperor © The Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing)

Interior of album of Heart Sutra by the Qianlong Emperor © The Collection of The Palace Museum, Beijing.

The above Lotus Sutra is known to have been copied by the Qianlong Emperor to celebrate the birthday of his mother, the Empress Dowager Chongqing, and with its inclusion of longevity wishes in the brocade, the present volumes are likely also to have been produced by the Emperor for a similar, or the same, occasion, but nearly two decades earlier.

The present Sutra has a long collecting history in the West, that can be traced to Bernard Alfred Quaritch (1819-1899), a German bookseller, who in 1847 opened a bookshop in London, where he specialized in old and rare books and soon became the leading antiquarian bookseller worldwide. The company exists in London to this day.

Henry Yates Thompson (1838-1928) was a British newspaper proprietor and collector of illuminated manuscripts. Part of his collection was sold at Sotheby’s, beginning in 1919, when his eyesight began to fail, and part was donated after his death to the British Museum and is today kept in the British Library. The inside of the Sutra cover contains his well-known bookplate Ex Musaeo Henrici Yates Thompson (‘From the Museum of Henry Yates Thompson’).

James R. Herbert Boone (1899-1983) was a Baltimore art collector who left his entire home, the Oak Hill House, and his collection of Western paintings, sculpture, decorative art, and Chinese and Japanese works of art to Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, for whose benefit it was sold at Sotheby’s in 1988. His elaborate bookplate is equally pasted inside the Sutra cover.

The sale is also led by a group of 22 jades offered from The Art Institute of Chicago. Many of the works were previously held in the Nickerson Collection, gifted to the Art Institute in 1900 and exhibited in the museum the same year. Highlights of the collection include two exceptional Qing dynasty jade brushpots, A Rare White Jade ‘Imperial Procession’ Brushpot (estimate $800,000/1,200,000) and A Finely Carved Spinach-Green Jade ‘Scholars’ Brushpot (estimate $400/600,0000), each fashioned from superlative quality stone and deeply carved in the round to form a virtual diorama. Produced during the mid-Qing dynasty, the cylindrical forms of jade brushpots yield a suitably large, continuous, and regular pictorial surface onto which they could translate complex compositional narrative scenes. Jade brushpots of this type possess not only the continuity of a scroll painting but also the volumetric illusionism of sculpture.

Lot 572. A Rare White Jade ‘Imperial Procession’ Brushpot, Qing dynasty, Qianlong period (1736-1795); Height 6 1/4 in., 16 cm. Estimate 800,000 — 1,200,000 USD. Lot Sold 2,060,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the cylindrical body superbly carved in varying levels of relief with a highly animated continuous narrative scene, depicting twelve riders on galloping horses in a procession amidst a rocky landscape, the figures wielding swords, holding banners and drawing bows and arrows, divided by large branches of foliage and rockwork all beneath scudding skies and raised on five conforming low tab feet, the stone with scattered icy-white inclusions.

Sold by The Art Institute of Chicago.

Provenance: Collection of Samuel. M (1830-1914) and Matilda (1837-1912) Nickerson.

Gifted to The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, in 1900 (acc. no. 1900.733).

Literature: Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel M. Nickerson: presented to The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, 1900, cat. no. 2.

Note: Forming a virtual diorama, the present brushpot is an extravagant statement of luxurious refinement. The superlative quality of stone, subject matter and artistry reflect the power and accomplishment of the Qianlong period and the unparalleled ability to access such rarefied material and talent.

The combination of riders carrying ceremonial court implements and those wielding weapons imply that the scene is of an imperial outing in the mountain, perhaps for a hunt or simply to enjoy the natural ambiance. A closely related scene with riders bearing the same types of equipment in a forested mountain is carved into a large spinach-green jade brushpot in the collection of the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, obj. no. B60J29. The same collection also includes a spinach-green jade boulder depicting a hunt scene, wherein a group of riders amble along the path chatting, while others are in hot pursuit of fleeing tigers and deer (obj. no. B60J49). Additional large-format Qing jade carvings illustrating hunt scenes include a dark green jade brushpot in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, published in Masterworks of Chinese Jade in the National Palace Museum, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1969, cat. no. 36; a spinach-green jade brushpot from the National Museum of History, Taiwan, exhibited and published in Jade: Ch'ing Dynasty Treasures from the National Museum of History, Taiwan, National History Museum, Taiwan, 1997, cat. no. 30; a white jade boulder in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, exhibited and published in The Refined Taste of the Emperor: Special Exhibition of Archaic and Pictorial Jades of the Ch'ing Court, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1997, cat. no. 52; and a circular spinach-green jade table screen illustrated in Roger Keverne, Jade, London, 1995, pl. 138.

Beyond the exemplary carving, the quality of the stone itself testifies to the present brushpot’s production in the mid-Qing period. Prior to the 24th year of the Qianlong reign (1760), jade arrived at the imperial court in very small amounts. Yang Boda, in ‘The Glorious Age of Chinese Jade', Jade, London, 1991, p. 146, notes that by the 6th year of the Qianlong reign (1742) only 10 pristine jade objects and 66 jade fragments were in the Imperial Collection. Following the Western campaigns and subsequent access to an abundant supply of uncarved jade, jade carving flourished throughout the empire. The Ruyi guan (Imperial Department for Production) began recruiting skilled jade craftsmen, while at the same time it continued to send uncarved jade to the eight departments under the Imperial court, the most important of which was in Suzhou. Production was strictly controlled and each piece was carefully selected before being displayed at court.

The jade of this brushpot is remarkable for its even white tonality across such a large expanse of stone. The pale color allows light to filter through the material, bringing out the depths of the carving, thereby enhancing the three-dimensionality and vivacity of the scenes depicted. The inherent qualities of the stone, and the rarity of finding such a desirable and sizable block to work from, would undoubtedly have inspired the artisan to maximize the material's potential by carving a grand and complex scene into its surface. Other 18th century white or whitish-celadon jade brushpots intricately carved with figural scenes include an example featuring scholars and attendants at a riverside retreat, in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, published in the Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Jadeware (III), Hong Kong, 195, pl. 167; an example carved with a Daoist scene, formerly in the collection of Heber Bishop, and now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acc. no. 02.418.209; another, also from the Bishop Collection, bearing a scene of an immortal surrounded by attendants in a forest setting, sold in these rooms, 16th September 2009, lot 251; an 'Immortals' themed brushpot, formerly in the Kitsen Collection, sold most recently at Christie's New York, 17th September 2008, lot 329; a brushpot depicting sages walking amidst pine trees, most recently sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 7th April 2015, lot 3643; and a brushpot with the 'hundred boys' merrily playing in a garden landscape, from the collection of Robert E. and Katharine Chew Tod, sold in these rooms, 23rd March 2011, lot 612.

Lot 573. A Finely Carved Spinach-Green Jade ‘Scholars’ Brushpot, Qing dynasty, 18th century. Height 6 1/8 in., 15.6 cm. Estimate 400,000 — 600,000 USD. Lot sold 475,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

of cylindrical form with a shallow recessed base, meticulously carved in varied layers of relief with a continuous scene of six scholars accompanied by attendants all gathering in a garden setting with bamboo, pine, plantain, and wutong trees, and rockwork creating a harmonious environment around the tucked-away studios, swirling clouds above and a flowing stream beneath, two of the scholars seated at a table appreciating a painting, another pair drinking and conversing by a babbling brook, two others ambling along a balustraded path, the stone a deep emerald green mottled with paler green patches.

Sold by The Art Institute of Chicago.

Provenance: Collection of Samuel. M (1830-1914) and Matilda (1837-1912) Nickerson.

Gifted to The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, in 1900 (acc. no. 1900.733).

Literature: Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Samuel M. Nickerson: presented to The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, 1900, cat. no. 18.

A number of impressive spinach-green jade brushpots carved with 'elegant gatherings', or related idealized scholarly scenes such as the 'Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion' or the 'Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove' were produced in the 18th century, when blocks of large, good-quality jade became available and the art of jade carving was at its zenith. Excellent examples of this type include a Qianlong era green jade brushpot in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, which is carved with six scholars gathered at Zhu Xi ('Bamboo Stream'), and features a vignette similar to the one on the present brushpot wherein a scholar seated at a painting table is helped to wine by an attendant, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Jadeware (III), Hong Kong, 1995, pl. 169.

Other impressive spinach-green jade brushpots of this caliber and category that are held in major collections include one depicting the 'Gathering at the Orchid Pavilion', formerly in the Heber Bishop Collection, and now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, acc. no. 02.18.679; one with a four-character Qianlong mark and illustrating a literati gathering at Xi Yuan ('Western Garden') in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in ibid., pl. 168; and a brushpot deftly carved with the 'Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove' from the collection of E. L. Paget, illustrated in Stanley Charles Nott, Chinese Jade throughout the Ages: A Review of its Characteristics, Decoration, Folklore, and Symbolism, Rutland and Tokyo, 1962, pl. CXXVI.

See also a spinach-green jade brushpot carved with the 'Seven Sages of the Bamboo Grove' and inscribed with a Qianlong mark and a date corresponding to 1776, from the Concordia House Collection, which sold in these rooms, 19th March 2007, lot 50; a 'scholarly gathering' green jade brushpot, formerly in the collection of the Fogg Museum of Art at Harvard University, sold in these rooms, 18th March 2008, lot 16; and an imperial spinach-green jade brushpot carved with a scene from Xi Yuan ('Western Garden') and a 39-character imperial poem with a date corresponding to 1748, from the collection of Charles Gaillart de Blairville (b. 1821), sold at Christie's Paris, 15th December 2010, lot 106.

INDIAN, HIMALAYAN & SOUTHEAST ASIAN WORKS OF ART

Auction 21 March @ 10:00AM

The week continues with an array of objects created over the course of 20 centuries in South Asia and the Himalayas, including sculptures in bronze and stone such as an impressive 7th Century Buddha from Eastern India, as well as fine miniature paintings and ritual and devotional works such as a spectacular cloth painting (Paubha) from Nepal. A group of exceptional thangkas is led by A Thangka Depicting a Hevajra Mandala, numbered 26th in a series of which at least 18 other paintings are known (estimate $800,000/1,200,000). The series represents perhaps the finest of all mandala painting from Tibet in the fourteenth century. Designed and painted with exquisite attention to detail and vibrant palette, this painting has been unseen since it was first acquired by a collector in the early 1970s.

Lot 936. A Thangka Depicting a Hevajra Mandala, Tibet, Second half of the 14th Century, Circa 1370-1380;33 by 29 1/2 in. (83.8 by 75 cm.). Himalayan Art Resources item no. 13601. Estimate 800,000 — 1,200,000 USD. Lot sold 2,420,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

in the form of a circular multi-colored lotus bearing a vimana palace and five forms of Hevajra depicted within inner chambers, with the blue eight-headed, sixteen-armed, four-legged Akshobya-Hevajra at the center embracing his consort Vajra Nairatmya and dancing on prostrate mara, red Amitabha-Hevajra with his consort Pandara Vasini in the chamber above, yellow Ratnasambhava-Hevajra with Buddha Lochani to the left, green Amoghasiddhi-Hevajra with Samaya Tara to the right and white Vairocana-Hevajra with Vajradhatvishvari below, each manifestation accompanied by eight dancing goddesses including Vetali, Dombini, Ghashmari, Pukkashi, Gauri, Shavari, Chauri, and Chandali, a further eight dancing goddesses and eight kalasha surrounding the chambers on the segmented yellow, red, green and white scrolling vine ground, with four gates at the cardinal points protected by vajra issuing from the mouths of makara, all enclosed by a ring of multi-colored flames and the eight charnel grounds, with Sakya hierarchs and dancing goddesses surrounding the mandala within scrolling vine on a flower-strewn blue ground, a Sakya lineage in the upper register, and dancing goddesses, protector deities and gods of wealth in the lower register, with the officiating monk to the right seated next to a table bearing ritual offerings, with the title ‘Mandala of the Five Dakas’ and numbered 26 in an inscription beneath the offering table, a painted floral border to the left and right, both edged with green silk, the upper and lower textile mounts now removed.

Property from the Estate of Johannes Dutt

Provenance: Acquired 1975.

Paintings from this series were first published, and recognized as masterpieces of early Tibetan art, by Robert Burawoy in his seminal exhibition catalogue Peintures du monastère de Nor, Paris, 1978, which featured four of the mandalas. Paintings from the set are now preserved in private and museum collections worldwide, including the Guhyasamaja mandala in the Margot and Tom Pritzker Collection, see Pratapaditya Pal, Tibet: Tradition and Change, Albuquerque, 1997, p. 146, pl. 73; the Jnanadakini mandala in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, see Steven M. Kossak and Jane Casey Singer, Sacred Visions, New York, 1999, p. 163, cat. 46; the Nairatmya mandala in The Cleveland Museum of Art, acc. no. 1993.4; and the Vajradhatu mandala in a private collection, see Jane Casey, Naman Ahuja, David Weldon, Divine Presence, Barcelona, 2003, p. 148, cat. no. 48. For others in the series and further discussion on the historical importance of the paintings see Pratapaditya Pal, Tibetan Paintings, Basel, 1984, pls. 29-31; Amy Heller “The Vajravali Mandala of Shalu and Sakya: The Legacy of Buton (1290-1364)” in Orientations, Hong Kong, May 2003, pp. 69-73; and Jeff Watt, himalayanart.org, set no. 2083, where Watt suggests the paintings may have been dedicated to Lama Dampa Sonam Gyaltsen by his devoted student Chen-nga Chenpo (1310-1370). The series may thus have been commissioned around the time of Chen-nga Chenpo’s demise in 1370, or possibly around 1380 as a memorial to Lama Dampa. For further study of this Hevajra mandala see Jeff Watt, himalayanart.org, no. 13601.

The series represents perhaps the finest of all mandala painting from Tibet in the fourteenth century. Each mandala is designed and painted with the same exquisite attention to detail and vibrant palette. While the overall format and dimension of the paintings remain the same throughout the series, the shape and size of the inner palace expands or contracts depending on the iconographic complexity of each focal deity and the extent of their retinue. The artist of the Hevajra mandala had to extend the corners of the palace walls to the outer limit of the ring of lotus petals to accommodate the five individual chambers within the palace grounds, which in turn compresses the arches of the vishvavajra gates, cf. the more voluminous vajra arches and compact palace grounds of the Jnanadakini mandala in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, see Kossak and Casey Singer, op. cit., p. 163, cat. 46. The gates of the Hevajra mandala are given added mass with double vajra prongs emerging from twin makara heads on each side of the gates: the majority of the mandalas in the series have only one makara head and vajra prong at each side, with a further exception of the Chakrasamvara in a private collection, see Jeff Watt, himalayanart.org, no. 77204, that also has twin vajra prongs and makara heads. The resulting composition fills the inner ground of the mandala palace leaving little empty space in one of the most dynamic and aesthetically pleasing of all the paintings in the set. The format of a ring of multi-coloured lotus petals and flames, the circle of charnel grounds and the surrounding scrolling vine supporting deities and monks against a flower-strewn blue background is consistent throughout the series, as is the painted floral border to either side: albeit in some of the mandalas, such as the Metropolitan Museum’s Jnanadakini, the scenes in the charnel ground are painted against a black ground, and others, like the Hevajra, have a light blue setting. The linear format of the upper and lower registers, depicting deities and religious figures on lotus pedestals beneath lobed arches, remains the same throughout the series: the presiding monk and altar table however can be placed at either end of the lower register.

Although the Hevajra is a Tibetan Sakya order work, the painting style is Nepalese and it is most likely to have been done by a Newar artist. Nepalese artists were working for Sakya patrons since at least the thirteenth century, when Aniko (1245-1306) travelled from Nepal to fulfil a commission for the Sakya hierarch Phags-pa (1235-1280). In the fifteenth century, as David Jackson reveals, Kunga Zangpo (1382-1456), who founded the Sakya order Ngor monastery in 1429, commissioned itinerant Newar artists to paint a series of Vajravali mandalas, see David Jackson, A History of Tibetan Painting, Wien, 1996, p. 78. Compare the style and movement of the Hevajra mandala’s dancing goddesses and figures in the charnel grounds with the vignettes of the thirteenth century Sakya order Virupa in the Kronos Collection painted in the Nepalese style, see Kossak and Casey Singer, op. cit, p. 136, cat. 35; and the stylistic provenance in a contemporaneous Vasudhara mandala, formerly in the Stuart Cary Welch Collection, painted by the Newar artist Jasaraja Jirili in 1365 for Nepalese patrons in the Kathmandu Valley, see Sotheby’s London 31 May 2011, lot 84; compare also figures within scrolling vine on a flower-strewn background of the late fourteenth or early fifteenth century Nepalese Chandra mandala formerly in the Jucker Collection, see Sotheby’s New York, March 28, 2006, lot 3; and compare the format and style preserved in fifteenth century Ngor monastery Vajravali mandalas documented as the work of Newar artists, see Kossak and Casey Singer, op. cit, p. 165-71, cat. 47.

FINE CLASSICAL CHINESE PAINTINGS & CALLIGRAPHY

Auction 22 March @ 10:00AM

The Fine Classical Chinese Paintings & Calligraphy sale will offer an outstanding group of works with exceptional provenance. The auction is led by Poems on Falling Flowers in Running Script, a rare and extraordinary handscroll previously collected by Wu Hufan and kept in wonderful condition, written by Shen Zhou in the style of Huang Tingjian during his late period (estimate $1.2/1.8 million). Following the loss of his son, Shen Zhou wrote a set of ten poems with a falling flower theme, perhaps inspired by seeing their colors in nature or because he was then able to allow his feelings of sadness to be expressed. In the spring of 1504, Shen Zhou shared these poems with his students at the Wu School, who composed poems in response, resulting in an exchange of 90 poems which became a celebrated story in the study of Chinese calligraphy and literature. The sale also features an exceptional Lotus and Rock painting by Chen Hongshou (estimate $1/1.5 million). Marked by exceptional provenance, the work was previously in the private collection of modern ink master Zhang Daqian.

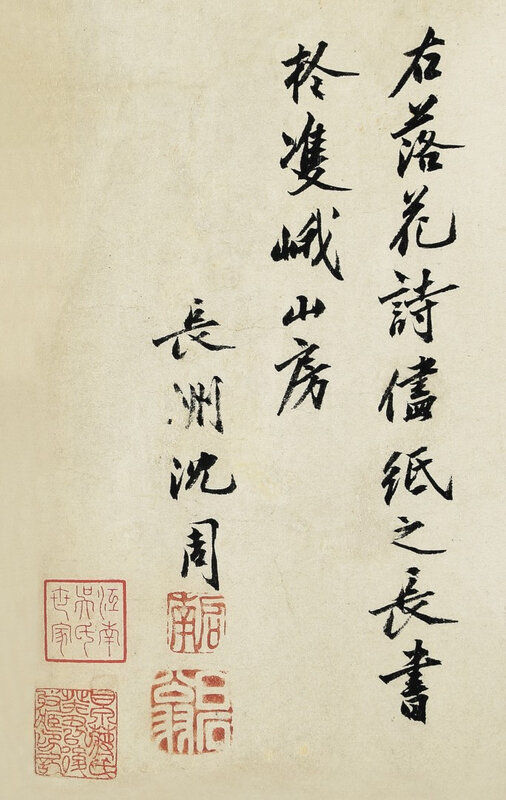

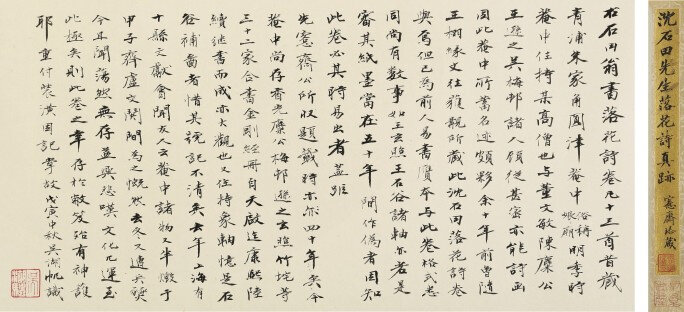

Lot 1168. Shen Zhou, Poems on Falling Flowers in Running Script, ink on paper, handscroll, 28.5 by 286 cm. 11 1/4 by 112 3/4 in. Estimate 1,200,000 — 1,800,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

The setting sun, that vagabond, west of the little bridge;

Spring scenes now fading, feelings so confused.

Before the gate of Broidered Village the stream still good for laundry;

Inside the shrine on Yellow Ridge the birds yet chattering.

To burn, seeking conch-dust incense to give the priest in charge;

To fry, bringing cow-milk cheese, instructing the kitchen maid.

Jewels, hairpins by the thousands ? Alas, none of them out here!

Returning home, all they want are baskets for carrying blossoms.

The day the fragrance dies away is the season of new life.

These plum girls, and these peach blossom maidens all give birth to children!

But now, folks have dispersed, the wine wears out, and spring too takes departure:

The reds diminish, the greens expand - no, nature has no feelings.

Envy of surplus silken beauties? Leave it to the rich neighbor.

But scattering, like patterned writings! - they brush the ground so low...

In vain I remember when I was young, those arenas of hairpins, dances...!

Gone, all gone, and now, today, only temple hairs like white silk remain.

Together they bring such springtime sadness to this traveler's brow;

Chaotically, in wild profusion as I stand here long.

I think of summoning the Green Maiden, but it's hard to form the chant!

I'd playfully compare them to Red Child, but - tedious to write so many poems!

I overlook the river, eastern breezes riffling my short temple hairs;

Perfuming the air, the clear-sky sun joins their wandering threads.

And now I follow the butterflies, pursuing them as they fly:

At the wall's corner, now appearing, a half-branch hiding there!

Wealthy, offering riches galore, spring filling every tree!

Then fragrance floats, petals drop, the trees are poor again.

The red and fragrant now sloughed off - immortals achieving the Way!

The greenery begins full shade - a son cultivating humaneness.

While some are added to swallows' nests - the mud receiving grace - Others are made into honey by bees; liquid made divine.

Year after year, there is one who grieves yet more for you:

The moth-browed beauty, she who still remains unmarried yet.

Floating, floating, sailing, dancing, far away from home:

From down below I trace their path back up to the treetop.

Chao Wu would grasp their shame, rain-driven to 'mud and plaster';

The Palace of Ch'in would surely regret the smearing of their rouge!

Wild in feeling, loving wine, they stick to the red sleeves;

Driven, hurried, threading the blinds, mooring on jade hooks!

Oh! I would gather these fragmented flowers, pound them into a pill,

But, grieved by spring, too hard to heal, the sorrow here, in me.

Jade bridles, silver jars - grown weary of the journey,

Flying east or falling west, now they make us sad.

Rapidly escorting spring away, first they part from trees;

Faint, supported by the wind, they barely reach the pavilion.

Fish-bubbles of life, some powdery pollen remains;

Spider-threads of love, tiny red bits still cling.

Their color, their fragrance - long mired in the realm of the senses:

But contrition, repentance? How could they ever emulate Buddhist nuns?

And who has twisted, crushed them to piles of broidered cloud,

Touching earth, spread on the ground, supported by the moss?

Sadness, resentment born at night from my pillow, hearing rain;

Sinking, floating, entering next morning my 'Farewell, Spring!' cup of wine.

Among the branch tips, a few remain, still stolen by the warblers;

Fluttering, riding the back of the breeze, tailorbirds press them on.

The blink of an eye! The Rise and the Fall! The whole just worth a laugh!

In the end, why is it that they drop? Why is it that they're born?

Along the twelve boulevards, the pleasure-seekers roam:

But now red rain, filling the avenues, thwarts them with spring grief.

They realize that time flows on, so difficult to hold back!

They waken to the emptiness of the material world, and contemplate withdrawal.

Now at dawn, they regret the insensitivity of servants' sweeping petals;

Returning late, are saddened by horses' trampling them underfoot.

Yet the next day, again they boast of 'cherry lips', 'bamboo-shoot fingers':

With Miss Green Leaf, Miss Yellow Oriole, at the old pleasure-house again!

Yesterday's flowery glory dazzled our eyes when it was new;

This morning, in a twinkling, it's all turned to dust again.

Deeply ensconced within his gates, Yang Hsin has no visitors;

Sprawled at leisure in his pavilion, Chou Yu has drunken guests.

Tears of dew, misty snivel - we mourn the things that pass;

Snail-mucus, ant trails - we lament the lingering spring.

Gateways, walls, walking paths - all deserted now;

If the Prime Minister understood this time, he would not explode in rage.

An entire garden of peach and plum - they lasted but a moment;

White on white, red on red - whole trees stripped of them!

Pavilion? I marvel that the greensward's darkness is topped now by old white;

Window? I fret it's easily mottled, speckled by new red!

They have no way to float afar, as does the wanderer;

Thus they wither, fade away, just like an old man.

Next year, again they'll blossom, and surely that is good:

Another little poem again will show their flourishing and dying.

The 105 Days have gone by now in the twinkling of an eye!

Overnight, not a single tree not shaken by the wind.

Girls dancing, singing Stomping Songs, will conjure willows white!

Poets pouring, drinking wine, will chant of rainfall red !

Along Gold River they'll send their fragrance, far off with the waves;

On stairs of jade, seeking their shadows, in moonlight - nothing left.

While blossoming, deep in the courtyard locked securely away,

Now they float beyond the walls, to the west and to the east...

Wave upon wave they flutter in a blur, cannot be clearly seen;

A downpour's time - the fragrant trees have lost their soul and spirit!

Yellow gold could not refine the longevity's root for them;

Reddish tears in vain lament the brevity of spring life.

Upon the sward, a few remain, temporary traces left;

On roads, some ground into mud beneath pleasure-seekers' horses.

Everybody will be preparing wine to be drunk next spring;

Ashamed of lingering to see them again there's only this old man."

Wildly, wildly, thickly, thickly, sideways, slantwise too;

How can we bear their delicacy, their lightness on the air?

'Adhering to mud' like Master Liao - but no sign of his craziness!

'Clinging to this thing', Old Man P'o earned a name for wrong.

Seeing off rain, seeing off spring, at the Temple of Long Life, Flying hither, flying thither, in the city of Loyang!

Please, do not hold a grudge against the wind and rain today!

The Creator of Things has always placed a 'taboo on exorbitance'.

(Translation courtesy of This Single Feather of Auspicious Light.)

signed Changzhou Shen Zhou, inscribed "above are my Poems on Falling Flowers, exhausting the length of the paper at Shuang-e Mountain Studio", with two seals of the artist, qi nan, bai shi weng

Titleslip by Wu Hufan (1894-1968)

Titleslip on mounting boarder by Wu Dacheng (1835-1902), signed Kezhai

Wu Hufan's inscription:

To the right is a handscroll of Falling Flowers poems written out by the venerable gentleman, Shih-t'ien (Shen Zhou), thirteen poems in all. It was originally collected in the Yüan-chin Temple (the Ch'an Buddhist Temple of the Perfected Ford, popularly known as the Young Lady’s Shrine) at Chu-chia chiao (Chu Clan Corner), Ch'ing-pu (a small town west of Shanghai, in the direction of Lake T’ien-shan and of Suchou; now part of the Greater Shanghai Industrial Corridor). During the late Ming period a certain distinguished monk, who was in charge of the temple, maintained extremely intimate relations with such men as Tung Wen-min (Tung Ch’i-ch’ang), Chen Mi-kung (Ch’en Chi-ju), Wang Hsün-chih (Wang Shih-min) and Wu Mei-ts’un (Wu Wei-yeh). And he too was good at poetry and painting. For this reason, the masterpieces collected in his temple were quite numerous.

Ten years ago, together with Wang Hsü, Yüan-wen, I travelled there and was able to view the works there collected, and this handscroll of Falling Flower poems by Shen Shih-t’ien was included among them. I myself considered that some former man had produced a fake which was perfectly congruent with this handscroll in layout and form. There were a few other items as well, such as hanging scrolls by Wang Hsüan- chao (Wang Chien) and Wang Shih-ku (Wang Hui) which seemed to be of the same type. When one examined the paper and ink (of the fakes) it appeared that they must have been executed within the last fifty years. And thus I realised that the present scroll too must have been substituted for there (by a fake version) within the same sort of period. For it was just forty years ago that the label (of this original) was inscribed by the late Master K’o- chai (Wu Ta-ch’eng).

At the present time, in this temple there exists an album of the Chin-kang ching (the Diamond Sutra) as calligraphed by Ch’en Chi-ju, Wu Wei-yeh, Wang Shih-min, Wang Chien, Chu-ch’a (Chu I-tsun) and so on - a total of thirty-two hands working together. It was created in successive stages from the T’ien-ch’i through K’ang-hsi periods (i.e. circa 1621 - 1722) and is indeed an object greatly worthy of viewing. There is also a hanging scroll portrait of that monk in charge of the temple, and it is remembered that Wang Hui added in its landscape elements; but unfortunately the signature cannot be clearly read.

Last year in Shanghai there was a conference on Literary Documents from Ten Counties, at which I heard a friend of mine claim that half the treasures of the temple had been destroyed by fire in the ‘battle of Ch’i and Lu’ of the year chia-tzu (1924); and I lamented to hear it. Also, last winter the temple again suffered the depredations of warfare, and now we hear that the place is in desolation, and practically nothing remains. Alas, this gives rise to great sadness at the extreme fate to which cultural objects may be exposed. Thus for this handscroll to have survived among the tattered scroll-baskets, must it not have enjoyed divine protection?

(Translation courtesy of This Single Feather of Auspicious Light.)

Colophon signed Wu Hufan, dated wuyin (1938), the eighth lunar month, inscribed "on the occasion of the scroll being remounted, I have recorded this account”, with one seal, wu hu fan

With five collector's seals of Wu Hufan, wu hu fan zhen cang yin, mei ying shu wu, wu shi tu shu ji, wu (3), jiang na wu shi shi jia, and one other collector's seal, gan quan jiang shi gui chou yi hou shou cang yin ji.

Provenance: Yuanjin temple collection.

Wu Dacheng collection.

Wu Hufan collection.

Yu-te tang collection.

Literature: This Single Feather of Auspicious Light: Old Chinese Painting and Calligraphy, Vol. I, London: Sydney L. Moss Ltd., 2010, cat. no. 1, pp. 24-33.

Note: Shortly after Mid-Autumn Festival in 1502, Shen Zhou, then aged 76, suffered the loss of his son1. By late spring of the following year, having gradually recovered from his griefing, he wrote a set of ten poems on the theme of falling flowers, perhaps inspired by their occurrence in nature seeing their colors or because he was then able to allow his feelings of sadness to be expressed. In the spring of 1504, Shen Zhou shared these poems with Wen Zhengming (1470-1559)2. After reading them, Wen and Xu Zhenqing (1479-1511) each composed ten poems titled “In Response to Master Shitian’s ‘Falling Flowers’”. Three of Wen’s poems and six of Xu’s were written to match the rhyme scheme of Shen’s originals. After reading their compositions, Shen Zhou was inspired to compose ten more poems in response to them. In 1505, Wen Zhengming called upon the high minister Lu Chang in Nanjing and presented him with Shen Zhou’s original verses, to which Lu composed ten poems in response. Very pleased, Shen Zhou in turn composed ten new poems in response to Lu. Later, Tang Yin (1470-1524) wrote thirty poems using Shen Zhou’s rhyme scheme. The creation and exchange of these poems on falling flowers, 90 in all, by the Wu School literati artists, became a celebrated story in the study of Chinese calligraphy and literature. Shen Zhou’s poems were first documented in literary anthology Shitiangao, printed in three volumes in 1503 by Huang Huai (16th Century) of Jiyitang3. Wen Zhengming’s calligraphic rendition, in small regular script, of the poems and the story of their creation is considered the authoritative primary source4.

The earliest work of art by Shen Zhou on the theme of falling flowers, dated September 5, 1503, is his calligraphic rendition of the poems in running script in the collection of Shanghai Museum (Fig. 1). Here, the artist writes in an inscription, “Ruqi, who is fond of poetry, recently came across my ‘Falling Flowers’ poems and requested that I write them for him. As I happened to be suffering from a minor illness, I was quite displeased to be badgered by him, and thought his request quite unreasonable. But he was redeemed by his fondness for poetry, and in the end, I agreed to write the poems for him.” Despite complaining about Ruqi’s assertiveness, Shen Zhou was ultimately won over by his love of poetry. Throughout the scroll, Shen’s calligraphy is fluent and assured, fully embodying the force of his personality, suggesting Shen’s pride in his poems. Based on his self-inscription on this scroll, the manuscript of Shitiangao (not divided into volumes) at the Beijing Library, and the Jiyitang printed edition, we can date the composition of Shen Zhou’s ten poems on falling flowers to the first half of 15035.

After the Shanghai Museum handscroll came Shen Zhou’s Poems and Paintings on Falling Flowers now in the Nanjing Museum. This scroll features a frontispiece by Wang Ao (1450-1524), a painting of falling flowers by Shen Zhou, as well as a calligraphic rendition in running script of all of his thirty poems on the theme. Shen writes in his inscription, “… In the spring of 1505, I was sick for an entire month. When I recovered, the flowers on the trees had all fallen, covering the ground with red and white petals. Seeing their decay without having seen their blossoming, I could not help feeling sad. My encounter with the fallen flowers inspired me to compose verses entitled ‘Poems on Falling Flowers’. I obtained ten regulated quatrains and sent them to my dear friend, Zhengming, who passed them on to Jiubo, the High Minister. He responded with rhyming responses that far exceed my wretched creations! Just as Momu had no shame about herself, I stretched my abilities to respond [to Zhengming and Jiubo], accumulating a total of thirty poems…” According to this Nanjing museum scroll, Shen Zhou composed the first ten poems only in 1505, later than indicated by all the other records cited above. Moreover, as scholars have different opinions on the authenticity of this scroll6, it is therefore not a convincing source of reference.

The third work by Shen Zhou on this theme is Painting with Poems on Falling Flowers (Fig. 2) in the collection of the Taipei National Palace Museum, as part of the Shiqu baoji chubian anthology. It bears a frontispiece and a painting of falling flowers by Shen Zhou himself, followed by his calligraphic rendition in running script of ten poems—nine from the initial set of ten, and one from his response to Wen Zhengming and Xu Zhenqing. This scroll is undated. Following Shen Zhou’s calligraphy is Wen Zhengming’s calligraphic inscription and rendition of his own ten poems written in response to Shen, dated to June, 1508. According to the National Palace Museum, “the calligraphic rendition of poems on falling flowers on paper is a masterpiece by Shen Zhou from his later years. The calligraphy is entirely forceful and solid, with compact characters closely pressed together. The brush strokes are full of energy, and the rich ink tones vary from dark to light and wet to dry. It represents Shen Zhou's calligraphy in the style of Huang Tingjian (1045-1105)."7 Gao Shiqi, in his Jiangcun shuhua mu, records a work entitled Poems with Painting on Falling Flowers as "not sent to the court as a tribute"8. This may be none other than this Taipei Palace Museum scroll, although it does not bear any impressions of Gao Shiqi's collecting seals.

A publication of the National History Museum in Taipei, The Four Great Artists of the Ming Dynasty: Shen Zhou, Wen Zhengming, Tang Ying and Qiu Ying, records another scroll by Shen Zhou entitled Poems on Falling Flowers9, which is fourth in our discussion here, includes in running script all of Shen Zhou's thirty poems, divided into three groups of ten and arranged roughly in approximate chronological order. The self-inscription on this scroll dates it to early summer of 1489, which, if accurate, would connote that Shen Zhou had finished all thirty poems by age 62, much earlier than indicated in all the records cited above. Thus this scroll is of uncertain authenticity and cannot be used as a definitive reference. The collectors’ seals impressed and the colophon by Luo Jialun (1897-1969) on this scroll indicate that it belonged to Liu Shu (Late 18th-Early 19th Century) and Zhuo Minyuan (19th Century) during the late Qing dynasty and was later acquired by Luo Jialun, who gave it to Wang Shijie (1891-1981) as a gift. The present location of this handscroll is unknown. Some sources suggest that it is in the Taipei National Palace Museum but it is not listed in the museum's electronic database.

Neither a fifth related work, Shanghai Museum's fan painting on gold-leafed paper of Falling Flowers, nor a sixth, the Zhejiang Provincial Museum’s calligraphic fan, Falling Flowers, in running script, both attributed to Shen Zhou, are comparable to the present lot10. Wuyue suojian shuhua lu records a monumental hanging scroll painting by Shen Zhou of Poems on Falling Flowers11, and Zhenji rilu records a painting of Falling Flowers by him12. Neither work appears to be extant. Pingsheng zhuangguan records a work of calligraphy of Poems on Falling Flowers by Shen Zhou but notes neither its contents nor its format13. It is thus unclear to which work this record refers. The above are all the known works by Shen Zhou on the theme of falling flowers searchable in the public domain.

The present lot is Shen Zhou’s calligraphic rendition in running script of the ten original poems on falling flowers along with three of the poems he wrote in response to Wen Zhengming and Xu Zhenqing. It is undated. According to Wu Hufan’s long colophon, this scroll belonged to Yuanjin Temple in Zhujiajiao, in present-day Qingpu District of Shanghai. This temple, whose successive abbots were accomplished poets, and painters and associates of literati, was renowned for its collection of paintings and calligraphy, which included a compendium of Diamond Sutra manuscripts copied by Dong Qichang (1555-1636), Chen Jiru (1558-1639), Wang Jian (1598-1677), and twenty-nine other well-known calligraphers who lived during the Ming and Qing dynasties. The collection became dispersed during the wartime chaos and some of the works were replaced with forgeries. After leaving Yuanjin Temple, the present lot likely entered the collection of a certain Jiang of Ganquan (otherwise undocumented) and then was bought by Wu Dacheng (1835-1902) at the close of the 19th century. It was then passed on to Wu Hufan, who remounted it in 1938, wrote a long colophon on it, and impressed seals on its seams. As a work of calligraphy, this scroll is no doubt one of the finest examples of Shen Zhou’s writing in the style of Huang Tingjian. Every stroke is confident and crisp. Compact and held in formal tension, the characters are tilted but linked in a continuous and steady flow of energy, as if they were a natural phenomenon. In his inscription, Shen Zhou ends with a note of contentment, writing that he had “exhausted the length of the paper”. Having finished writing the poems, he was still inspired to write some more. This work of art is the closest to the Shiqi baoji version at the Taipei National Palace Museum in terms of calligraphic style. The museum's work is dated to 1508, and the present lot should date very close to this year.

Also notable is that Wu Hufan made three impressions of a “seam-riding” seal after he had the scroll remounted. The first impression can be found between the last and next to last sentence of the poem beginning with fangfei siri. Here is no obvious seams between pieces of paper, but the blank space shows signs of restoration. The second impression occurs before the poem beginning with fucheng nonghua. Here the paper suddenly darkens and shows a clear seam. Generally, the opening parts of a handscroll, bearing the most wear from unrolling and rolling, tend to suffer from discoloration most easily. The third impression occurs before the poem beginning with zuori fanhua. Here the paper’s color also changes, and shows an obvious seam, indicating that when Wu Hufan had the scroll remounted, he might have moved the five poems between fucheng nonghua and shier jietou from the middle part of the scroll in order to avoid further damage. Thus, the scroll in its original state started with the fucheng nonghua poem, which is consistent with the Jiyitang printed edition and Wen Zhengming’s manuscript in small regular script14.

1. Shen Yunhong, Shen Zhou’s eldest son, died on the seventeenth day of the eighth lunar month in 1502. See Chen Zhenghong, Shen Zhou Nianpu, Fudan University Press, 1993, p. 269.

2. In the eleventh lunar month of 1503, Shen Zhou buried his son and invited Wen Zhengming to write his epitaph (ibid., p. 272). Thus, it is not surprising that Shen Zhou showed Wen Zhengming his new poems.

3. Shitiangao (three volumes), printed by Huang Huai of Jiyitang, features prefaces by Peng Li (1443-?), Wu Kuan (1435-1504), Tong Xuan (14252-1498), and Li Dongyang (1447-1516), and postface colophons by Jin Yi (Early 16th Century) and Huang Huai. Shen Zhou was 77 years old at the time of the printing.