Exclusively in Cleveland: rarely seen Japanese treasures offer encounters with the divine

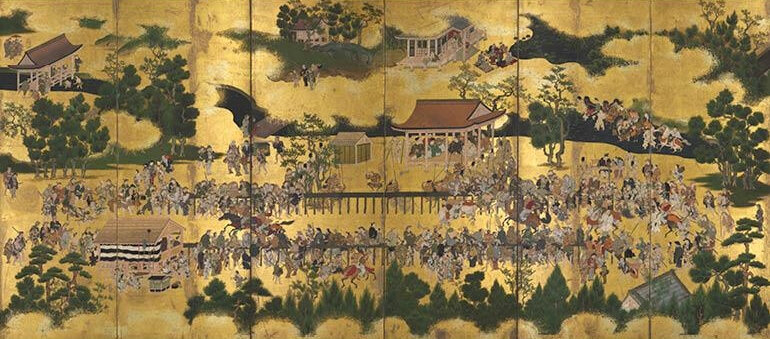

Horse Race at the Kamo Shrine, c.1634–44. One of a pair of six-panel folding screens, ink and color on gilded paper; image: 176.5 x 337.3 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund, 1976.95.1.

Horse Race at the Kamo Shrine (detail), c. 1634–44. One of a pair of six-panel folding screens, ink and color on gilded paper; image: 176.5 x 337.3 cm. The Cleveland Museum of Art, Purchase from the J. H. Wade Fund, 1976.95.1.

CLEVELAND, OH.- A major international loan exhibition of great importance, Shinto: Discovery of the Divine in Japanese Art presents artworks of Shinto, Japan’s unique belief system focused on the veneration of divine phenomena called kami. Organized by the Cleveland Museum of Art, with the special cooperation of the Nara National Museum, the exhibition presents about 125 works in different media—calligraphy, painting, sculpture, costume and decorative arts—assembled from Japanese and American museums, shrines and Buddhist temples.

The exhibition features artworks that are an expression of the everyday engagement of people with divinities in their midst. The exhibition includes treasures never before seen outside Japan and a significant number of works designated as Important Cultural Properties by the Japanese government. Works designated as Important Cultural Properties may be shown for no more than several weeks each year to balance accessibility with the preservation of the artwork.

Because of this and the light-sensitivity of other works on view, the exhibition will have two rotations: April 9–May 19 and May 23–June 30, 2019. Approximately 80 percent of the works on view during the first rotation will be replaced with entirely new works for the second rotation.

Seated Tenjin, 1259. Kamakura period (1185–1333). Wood with color; 94.9 x 101.5 x 68.8 cm. Yoki Tenman Jinja, Sakurai, Nara Prefecture. Important Cultural Property. Photo: Nara National Museum. First rotation (April 9–May 19).

“Shinto: Discovery of the Divine in Japanese Art is an extremely important international loan show and a project many years in the making,” said William Griswold, director of the Cleveland Museum of Art. “On view exclusively in Cleveland, visitors will have an unpreceded opportunity to view rarely seen treasures. We are grateful to all our collaborating institutions for their generosity in making these major loans, and we look forward to sharing the art of the Shinto religion with our global audience.”

Shinto means “Way of the Gods.” Although Shinto was officially established in the late 19th century, there is a long tradition of venerating kami in Japan. Shinto: Discovery of the Divine in Japanese Art focuses on that tradition from the 10th to 19th centuries.

Kasuga Dragon Box, 1300s. Nanbokuchō period (1336–92). Lacquered wood with color; outer box: 43.3 x 52 x 44.7 cm, inner box: 37.8 x 38.6 x 37.6 cm. Nara National Museum. Important Cultural Property. Photo: Nara National Museum. First rotation (April 9–May 19).

Boxes for the Kasuga Dragon Jewels, 1300s. Nanbokuchō period (1336–92). Lacquered wood with color; outer box: 43.3 x 52 x 44.7 cm. Nara National Museum. Important Cultural Property. Photo: Nara National Museum (Outer box: rotation one, on view April 9–May 19; Inner box: rotation two, on view May 23–June 30).

“Kami veneration has been a central feature of Japanese culture and the inspiration behind a broad range of Japanese art for centuries,” said Sinéad Vilbar, the exhibition’s curator and curator of Japanese art at the CMA. “The exhibition explores the worship of kami and Buddhist divinities and celebrates the religious art ignited by their fusion. As a curator, this is a dream come true—to bring works of this caliber and importance to Cleveland and to introduce new audiences to some of the finest treasures of Japan.”

The earliest written histories in Japan describe kami as being creators of the islands of Japan and descending from the heavens to rule the land. Kami were responsible for all manner of tasks, from managing natural resources to protecting against disease, and they only descended to earth to special places in nature such as mountains, forests and waterfalls.

Seated Tenjin, 1261. Kamakura period (1185–1333). Wood with pigments; h. 83.5 cm. Egara Tenjinsha, Kamakura, Kanagawa Prefecture. Important Cultural Property. Photo: Nara National Museum. Second rotation (May 23–June 30)

After the arrival of Buddhism from continental Asia in the mid-sixth century, people began building shrines (jinja) for kami in emulation of the construction of temples dedicated to Buddhist deities. In the mid-eighth to mid-ninth centuries, it was believed that kami were avatars of Buddhist deities, and as a result many kami were assigned Buddhist counterparts; kami and Buddhist deities were worshipped side-by-side. This idea was widespread by the mid-11th century and continued to inform the perceived relationships between kami and Buddhist deities into the 19th century. However, kami remained distinct from Buddhist deities and were worshipped in different ways through entertainment, festivals and offerings. While the Buddhas and bodhisattvas of Buddhism are enlightened beings with virtues seen as out of reach for most humans, kami are more like people. They can exhibit generosity and cleverness, as well as pettiness and foolishness. Like nature, they can deliver great bounty, or be the source of tremendous devastation.

Shinto: Discovery of the Divine in Japanese Art is organized into six thematic sections that explore centuries of engagement with kami and Buddhist divinities.

Kasuga Mandala Reliquary Shrine, 1479. Muromachi period (1392–1573). Lacquered wood with color; 55.6 x 39.7 x 48 cm. Tokyo National Museum. Photo: TNM Image Archives. Second rotation (May 23–June 30)

Entertaining the Gods delves into performing arts and sport competitions held at shrines during festivals to entertain and appeal to the resident kami, including sculptures depicting sumo wrestlers and mounted archery, screens painted with scenes of horse racing and costumes used in performances of gagaku (traditional court music), bugaku (traditional court dance) and nō (masked drama).

Gods and Great Houses explores the historical relationship of kami veneration to powerful families and individuals of Japan’s elites, including dual focuses on Kasuga Taisha in Nara, the protecting shrine of the powerful Fujiwara family of the Heian period (794–1185) court, and shrines devoted to Tenjin, the deified form of ninth-century courtier Sugawara no Michizane.

Devotional Shrine with Image of Tenjin Visiting China, 1600s. Textile appliqué by Empress Meishō (1623–1696). Edo period (1615–1868). Lacquered wood, gold powder (maki-e), metal fitting, ink, and textile appliqué (oshi-e); h. 33.5 cm. Sata Tenjingū, Moriguchi, Osaka Prefecture.

Tenjin Shrine Scrolls (detail), 1600s. Edo period (1615–1868). Handscroll, ink and color on paper; 25.9 x 638.7 cm. Second scroll from a set of two. Minneapolis Institute of Art, Bequest of Richard P. Gale, 74.1.2.2.

Gods Embodied introduces the strong sculptural tradition associated with kami veneration. Kami are invited to reside in wood sculptures. The sculptures are often painted and may have special features such as sacred objects hidden inside. These sculptures are housed in shrine halls and are not visible to visitors. Visitors ring a bell to alert the deity to their arrival. This section features works that still belong to shrines and are rarely seen in public.

Moving with the Gods addresses festivals and pilgrimage. Many shrines are located within awe-inspiring natural environments and involve pilgrimage routes to and processional routes from these sacred destinations. Glorious screens depict the Hie-Sannō and Gion shrine festivals, as well as celebrations at Kitano Tenmangū and Yoshino, while large hanging scrolls show travelers making their way to the Kumano and Ise shrines.

Illustrated Scrolls of the Miraculous Origins of Matsuzaki Tenjin Shrine (detail), 1311. Kamakura period (1185–1333). Ink, color, and gold on paper; 34.2 x 1,420.5 cm. Second scroll from a set of six. Hōfu Tenmangū, Hōfu, Yamaguchi Prefecture. Important Cultural Property.

Record of 1,000-Linked Verse Session Held by Imagawa Ryōshun, “Fu nanihito renga (Linked Verses Devoted to “Person”), 1382. Nanbokuchō period (1336–92). Book: ink and color on paper; 16.5 x 47.5 cm. Dazaifu Tenmangū, Dazaifu, Fukuoka Prefecture.

Combinations: Kami and Buddhist Deities clarifies the unique mingling of kami veneration with Buddhist religious traditions by considering topics such as star worship, mountain asceticism, Pure Land Buddhist incorporation of kami and the diversity of matching kami with Buddhist deities at various shrines. It also investigates the complex topic of shinbutsu shūgō (the matching of kami with Buddhist deities).

Gifts for the Gods features examples of gifts given to the kami. Some objects are given to kami in gratitude for assistance or in requesting help. Other gifts include the objects a kami needs for daily life, such as clothing, cosmetics and writing tools. Gifts are presented when a shrine is reconstructed or refurbished as part of a renewal of the kami’s spirit

Sacred Name of Tenjin Invocation and Seated Tenjin in Formal Court Attire, 1600s. Invocation by Emperor Go-Yōzei (Japanese, 1571–1617), painting by Kuroda Tsunamasa (Japanese, 1659–1711), inscription by Kakugen (Japanese, dates unknown). Hanging scroll, ink, color, and gold on silk; 169.4 x 51.9 cm. Dazaifu Tenmangū, Dazaifu, Fukuoka Prefecture.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_ac5c4c_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_709b64_304-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240418%2Fob_22f67e_303-1.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240417%2Fob_9708e8_telechargement.jpg)