Internationally acclaimed exhibition reveals the radical evolution of Monet's final decade

Claude Monet, The Artist's House Seen from the Rose Garden, 1922–24. Oil on canvas, 31 7/8 x 36 5/8 in. (81 x 93 cm). Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris, Michel Monet Bequest, 1966, inv. 5087.

FORT WORTH, TX.- Monet: The Late Years is the first museum exhibition in more than 20 years dedicated to the final phase of Monet’s career. Through approximately 50 paintings, the exhibition traces the evolution of Monet’s practice from 1914, when he embarked on a reinvention of his painting style that led to increasingly bold and abstract works, up to his death in 1926. The Kimbell’s deputy director, George T. M. Shackelford—one of the foremost experts on 19th-century French art—is the curator of the exhibition, which brings international loans from major public and private collections in Europe, the United States and Asia. Monet: The Late Years is on view at the Kimbell Art Museum from June 16 through September 15, 2019, in the Renzo Piano Pavilion.

Monet: The Late Years includes more than 20 examples of the artist’s beloved water-lily paintings. The exhibition also showcases many other extraordinary and unfamiliar works from his final years, several of which will be seen for the first time in the United States. A surprising range of paintings, from traditional pictures to canvases more than six feet high to a monumental work measuring 14 feet wide, demonstrating Monet’s continued vitality and variety as a painter. It redefines Monet as one of the most original artists of the modern age.

“In this glorious selection of paintings, we see bold methods of paint application, surprising harmonies or clashes of color and striking scale. Our visitors will encounter the radical nature of the painter’s late works,” commented Eric M. Lee, director of the Kimbell Art Museum. “I’m thrilled with the reception the show received in San Francisco—achieving international and national media acclaim—and I’m looking forward to seeing it here, bathed in the natural light of the Kimbell’s galleries.”

In 2016 and 2017, the Kimbell Art Museum and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco presented Monet: The Early Years, an exhibition of more than 50 paintings that surveyed the artist’s work from a picture exhibited in 1858—when he was 17 years old—to a group of paintings from the summer of 1872— completed when he was still just 31. Monet: The Late Years returns to take up the story of Monet’s art at the very end of his career—after the heady days of the explosion of Impressionism in the 1870s; after his exultant mastery of his medium in the 1880s and his recognition as chief of the Impressionist landscape painters; after the momentous decision, in the 1890s, to work in series; and after the first decade of the 20th century, which saw the debut of his views of the Thames in London in 1904 and his triumph with the Water Lilies exhibition of 1909.

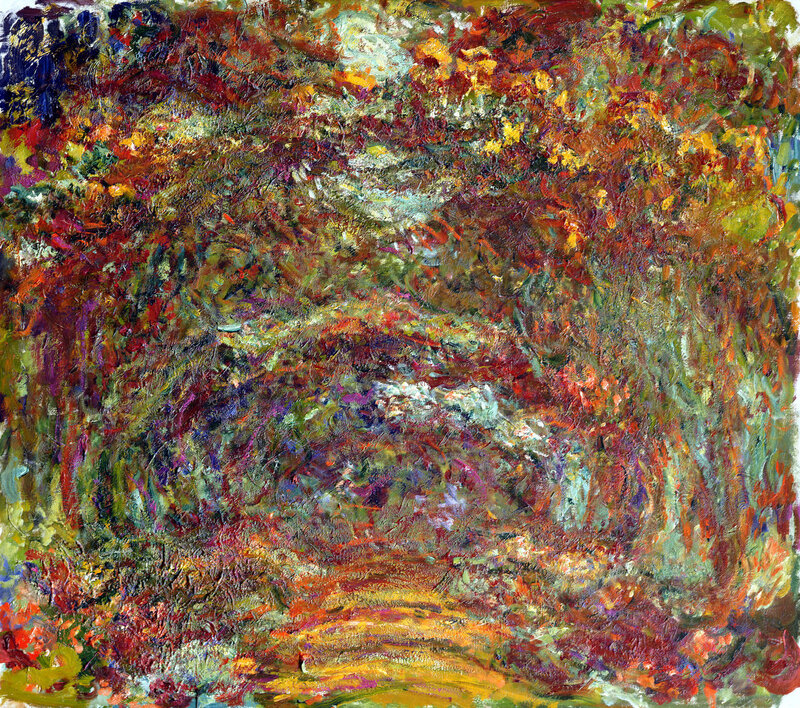

Claude Monet, Path under the Rose Arches, Giverny, 1918–1924, oil on canvas, 35 x 39.4 in. (89 x 100 cm), Musée Marmottan Monet, Michel Monet Bequest, 1966, inv. 5089. Photo © Kimbell Art Museum

Monet: The Late Years— though it opens with a prologue of works painted at the very end of the 1890s, a selection of the classic water-lily paintings of 1904–7 and the two views of his garden painted around 1913—begins in earnest with Monet’s return to painting in the late spring of 1914, tracing his career until his death in 1926.

“It is astonishing to see the change in Monet’s works when he returned to painting in 1914,” said Shackelford. “I have been excited to see the public’s reaction to these paintings, which are still unfamiliar to most people. And bringing things together that may not have been seen with each other since they left Monet’s studio—that is the thrill of an exhibition like this one.”

Claude Monet, Yellow Irises, 1914–17, oil on canvas, The National Museum of Western Art, Tokyo.

The spring of 1914 was a turning point for the artist. On April 30, Monet wrote to his friend Gustave Geffroy, an art critic as well as a novelist, that he was “doing wonderfully and . . . obsessed by the desire to paint; I’ve been prevented from doing so during the last, very beautiful, days, but I should have got myself back to work yesterday, everything was ready for me, and then voilà, time wasted, false start.” A month later, Monet was back to painting in earnest, telling the critic Félix Fénéon that he was “working at full speed, and no matter what the weather, I paint.” He went on to say that he was beginning “a huge labor, I am passionate about it.”

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1915-26, oil on canvas, Saint Louis Art Museum, The Steinberg Charitable Fund 134:1956.

The work Monet began in 1914 was exhausting. As he wrote to his dealer Durand-Ruel, “you know that when I set myself to something, I set myself to it seriously, so much so that waking up at 4 o’clock in the morning, I labor all day and, come nightfall, I collapse with fatigue.” The artist was anxious to share his new work with his friends. “It would be a great pleasure to see you,” he told Geffroy, “and also to show you the beginnings of the great work that I have begun, for you know that for the last two months I have been working nonstop.” The work was also revolutionary, a transformation that amounted to a break with the past and a new beginning. He had decided to accomplish, on a huge scale, the great work of his old age, the Grandes Décorations, installed in the Orangerie of the Tuileries Gardens after his death.

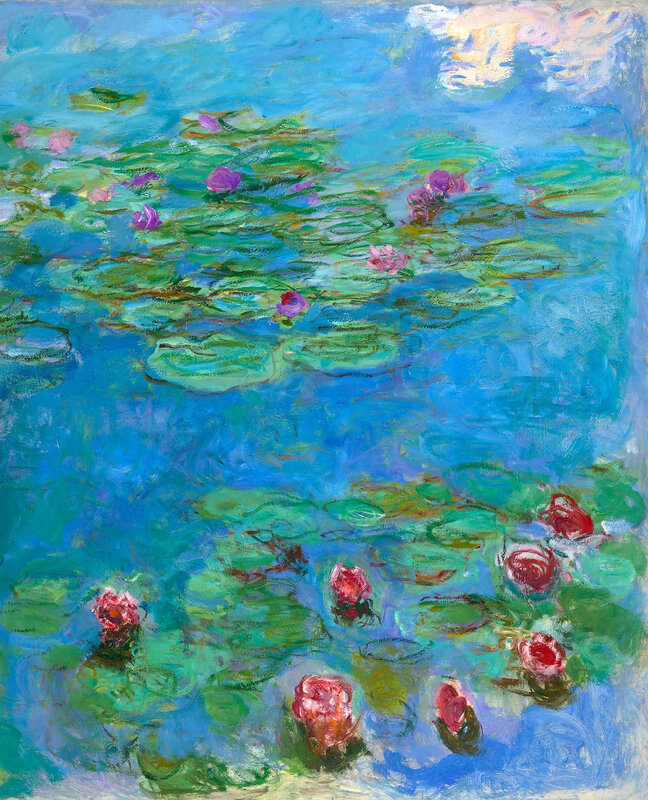

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1914-1917, oil on canvas, 71 x 57 1/2 in. (180 x 146 cm), Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, Museum purchase, Mildred Anne Williams Collection, 1973.3.

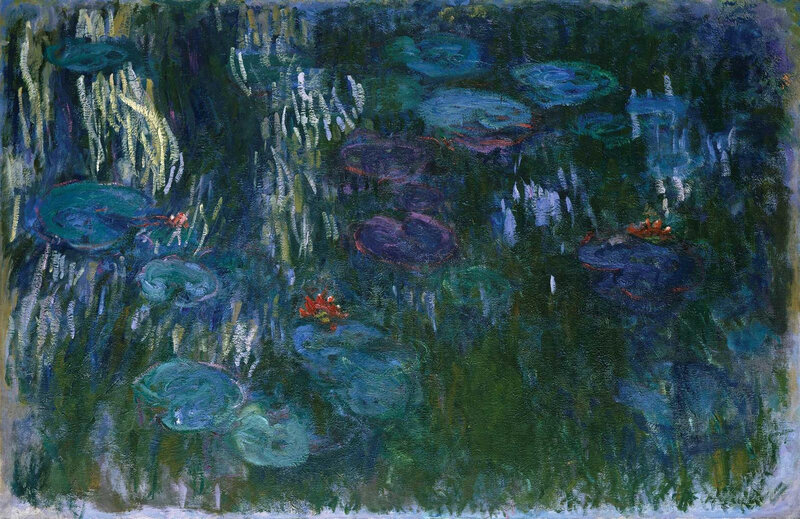

Deciding to return to ideas he had first explored at the end of the 1890s, he had come to the decision to begin his great project, the series of huge paintings, the most exhaustive he had ever attempted, on the theme of his water-lily pond. This work would absorb him from the time he was 73 onwards. And with the new project came a new way of working, a shift in the scale of every component of his art making. Among the works in Monet: The Late Years are some of the studies, each more than six feet tall, that Monet painted beside the water-lily pond to record the effects that he saw there, so that he could bring them back to his studio for imaginative recombination and extension. The Saint Louis Art Museum has lent one of the most beautiful of the large panels that were not, in the end, selected for the Orangerie, a stunning Water Lilies (Agapanthus) some 14 feet in width.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1922, oil on canvas, Toledo Museum of Art, Purchased with funds from the Libbey Endowment, Gift of Edward Drummond Libbey, 19811.54.

Going large, he found it difficult to scale his art back again, yet he did so brilliantly, transforming his way of painting at the same time to overcome the barriers placed in his way by his fading vision. Among the works that he undertook after 1918 are several series of views of the garden above the water line. In Monet: The Late Years, more of these works will be gathered together than ever before. These will include seven canvases depicting the Japanese bridge he had built over the narrowest spot in the pond and two showing the allée of rose arches leading up to his house. The Kimbell’s own Weeping Willow will be joined by four others, three from the Musée Marmottan Monet and one from the Columbus Museum of Art. Finally, the exhibition will close with four views of the artist’s house, seen from his garden, the architectural and natural forms flowing together in a mêlée of brushstrokes, each more colorful than the next.

Claude Monet, Corner of the Water-Lily Pond, 1918–19. Private collection..

As he entered his 80s in 1920, the “impressive yet fragile deity of the Seine,” as one visitor called him, had become something of a giant, even as his body and his physical capacities had steadily diminished. Monet saw his last works, however radical they might have become, as a continuation—we might now say a culmination—of a lifetime of studying nature. The attitude towards the natural world that gave the works of his youth their magic was, in the artist’s late years, the same. As the artist himself said, “My sensitivity, far from diminishing, has been sharpened by age, which holds no fears for me so long as unbroken communication with the outside world continues to fuel my curiosity, so long as my hand remains a ready and faithful interpreter of my perception."

Claude Monet, 'Nymphéas (Waterlilies),' 1914–1915. Oil on canvas, 63 1/4 in x 71 1/8 in. (160.66 x 180.66 cm). Portland Art Museum, Portland, Oregon. Museum Purchase: Helen Thurston Ayer Fund, 59.16

Claude Monet, Water Lilies, 1916–1919, oil on canvas, Lent by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Louise Reinhardt Smith, 1983 (1983.532).

Claude Monet, Water Lily Pond, 1917-22, oil on canvas, The Art Institute of Chicago, Gift of Mrs. Harvey Kaplan, 1982.825.

Claude Monet, Water Lilies and Agapanthus, 1914-17, oil on canvas, Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris.

Claude Monet, The Japanese Bridge, 1922–24, oil on canvas, Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F25%2F77%2F119589%2F129711337_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F68%2F22%2F119589%2F129020586_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F43%2F28%2F119589%2F128988697_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F84%2F73%2F119589%2F128782095_o.jpeg)