A Chinese ormolu, enamel and paste-set musical automaton clock, Guangzhou Workshops, Qianlong Period, circa 1790

Lot 20. A Chinese ormolu, enamel and paste-set musical automaton clock, Guangzhou Workshops, Qianlong Period, circa 179042¾in. 109cm. high. Estimate 600,000 — 900,000 GBP. Lot sold 1,215,000 GBP. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the three-tier case surmounted by an urn with revolving tree above the 3.5-inch enamel clock dial with gilt hands and centre seconds, the paste-set bezel with blue enamel surround decorated with gilt leaves, the rear-wound two-train chain fusee clock movement with verge escapement and rack striking on a bell, the main automaton scene below comprising a central figure holding a double gourd vase that he moves from side to side and from which emerge polished hardstone balls, these alternately roll down the left and right chutes supported by kneeling figures until disappearing into the mouths of Buddhist lions attended by further kneeling figures, the substantial automaton movement with chain fusee and playing a tune on a nest of eight bells, concealed within the base and powering a further automaton of revolving glass rods simulating running water, the ornate case finely cast and chased and set with panels of blue guilloche enamel decorated in gilt with flowers and scrolls.

Note: Opulently decorated clocks with ingenious and entertaining designs were perhaps the most extravagant works of art made during the Qianlong reign (1736-1795). These visually striking objects which combined Western and Chinese decorative elements in a highly innovative manner, were not merely sophisticated timepieces but also markers of the unrivalled wealth, power and influence of the Qing Empire.

The present clock is a sophisticated and rare example of clocks made entirely in China as tribute gifts to the Imperial court in Beijing. When striking on the hour, bells begin to ring, the floral arrangement in the vase above the dial rotates, while small beads representing seeds are released from the bottle gourd held in the hands of the central figure and disappear in the mouth of two recumbent lions. Flowing water is cleverly simulated by revolving crystal rods in the lower section of the clock, a feature that is often found on both clocks made in Guangdong and those made in Europe for export to China.

The fascination with mechanical clocks in China began in the late 16th and early 17th century, when the first clocks from Europe came to China. The arrival of the Jesuit Matteo Ricci (1552-1610) at the court of the Wanli Emperor (r. 1573-1620) began a long-lasting cooperation between Jesuits, who hoped their scientific knowledge would help to propagate their faith, and Chinese craftsmen. On his arrival in Beijing in 1601, Ricci presented two striking clocks to the Emperor, who later assigned him the task of teaching four eunuchs theory and practice of mechanical clockwork. As the eunuchs were deemed unable to maintain and repair the growing collection of clocks in Beijing, Jesuits were employed instead. The Imperial collection of European and Chinese clocks was vastly expanded under the direction of the Kangxi Emperor (r. 1662-1722), who created an office of ‘self-ringing bells’ (zimingzhongchu) in the Duanningdian (Hall of Solemnity), which later became the Imperial clock-making workshop, zaozhongchu. The collection was further enriched by the Qianlong Emperor, and it is said that during his reign ‘in every hall, on every wall and on every table there was a clock’ (Tributes from Guangdong to the Qing Court, Palace Museum, Beijing, 1987, p. 55).

The Qianlong Emperor’s fondness for sophisticated timepieces encouraged the emergence of regional centres for the manufacture of clocks in the European style, of which Guangzhou was the most important. Cognisant of the Emperor’s passion for these objects, ministers and high officials employed craftsmen from Guangzhou to produce impressive clocks that they could send as tribute gifts to Beijing. Guangzhou was the main point of contact for foreign trade and was also the first landing place for many Jesuit missionaries, thus Guangzhou craftsmen were exposed first-hand to foreign objects and technology. The first clocks produced by Guangzhou craftsmen were directly inspired by European prototypes, and often were fitted with European mechanical movements (Catherine Pagani, “Clockmaking in China under the Kangxi and Qianlong Emperors”, Arts Asiatiques, vol. 50, 1995, p. 80).

This clock epitomises the unique stylistic syncretism that developed in Guangzhou from the mid through the late 18thcentury. Features such as the sumptuous vine swags, luxuriant acanthus leaves, or the urn at the top of this piece were directly inspired by European designs, as were the female head on the back and the leaves ending in cockerel heads at the top. It is interesting to note that while the Imperial court as well as the craftsmen in Guangzhou considered the European clocks in China as representative of Western technology and art, European clockmakers designed these clocks in what they considered as Chinese style. As Ian White noted (English Clocks for the Eastern Markets, Ticehurst, 2012, p. 210), “This mutual ignorance was the source of a great mutual trade”.

While incorporating the sophistication and highly decorative nature of the European prototypes, clocks made in Guangzhou for the court often feature auspicious designs steeped in Chinese symbolism. Indeed, these clocks represented most suitable gifts to the court for special occasions, such as birthdays and weddings. On the present piece, a foreigner is depicted pouring beads, perhaps representing seeds, from a double-gourd vase, which would have evoked the concepts of fertility, male progeny, as well as longevity, while its network of vines and tendrils may represent continuity.

Ian White (ibid., p. 238), notes that clocks made in China share certain characteristics which are displayed on this piece, such as dials set against a finely decorated basse-taille ground – a technique introduced from Europe, but which soon became associated with Guangzhou clocks. Rotating flowers and figures, as well as the tiered structure of many of these clocks, are all features associated with Guangzhou. The latter is likely to have derived from English clocks, such as those made by James Cox for export to China, which were often made of different tiers that could be easily dismantled and replaced if damaged.

Two clocks with foreigners holding bottle gourds and similarly modelled in three tiers, are in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in Ni yinggai zhidao de 200 jianzhongbiao [200 objects you should know: Timepieces], Beijing, 2007, pls 34 and 35, together with a clock in the form of a neoclassical building with foreigners on its roof, pl. 25. See also a clock with Shoulao, the God of Longevity, and two assistants with bottle gourds, from the Nezu Museum, Tokyo, sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 27th May 2008, lot 1504.

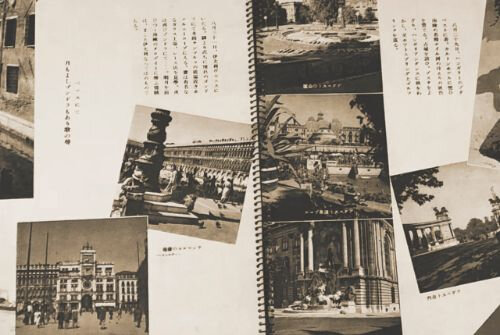

Grand Tours of the 18th and 19th centuries are well documented but it is less well known that they also continued well into the 20th century. For a wealthy young Japanese gentleman, it was fashionable to travel to see the great sights of Europe and America as well as Asia. Spectacular clocks such as this have always been highly prized and, having witnessed other examples during his personal Grand Tour during the 1930s, the grandfather of the current owner was determined to add one to his own collection. It is not known precisely where the clock was acquired but, as can be seen by his scrapbook and the labels on his luggage preserved by his family, figs. 1 & 2, his travel was truly extensive.

From the Vendor’s family archives.

From the Vendor’s family archives.

Sotheby's. Treasures, London, 3 july 2019

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F98%2F98%2F119589%2F129097971_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F93%2F75%2F119589%2F128489120_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F09%2F29%2F119589%2F128488304_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F62%2F18%2F119589%2F128488091_o.jpg)