'Baroque Pathways' Brings Rome to Potsdam

Caravaggio (1571-1610), Narcissus, 1598/99. © Photo: Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Roma – Bibliotheca Hertziana, Istituto Max Planck per la storia dell’arte / Mauro Coen.

Potsdam - From July 13 to October 6, 2019, Germany's Museum Barberini is presenting its first old master exhibition: Baroque Pathways: The National Galleries Barberini Corsini in Rome showcases 54 masterpieces from the collections of the Palazzo Barberini and the Galleria Corsini in Rome, among them an early work by Caravaggio, his painting Narcissus of 1597–1599. Tracing the birth of Roman Baroque painting in the wake of Caravaggio, its spread through Europe and development north of the Alps and in Naples, the exhibition explores the role of the Barberini as patrons of the arts and the Prussian kings’ yearning for Italy.

The Barberini at the Barberini

A selection of 54 masterpieces from the collections of the Palazzo Barberini and the Galleria Corsini has traveled from Rome to Potsdam. The Palazzo Barberini, the architectural inspiration for the Barberini Palace in Potsdam, holds one of the world’s most important collections of baroque paintings. Together with the Galleria Corsini, it is home to the Italian national galleries. Ortrud Westheider, Director of the Museum Barberini: “It is a great honor and a mark of recognition for the still young Museum Barberini to cooperate with the illustrious national galleries. It has always been our dream to collaborate on an exhibition with our renowned namesake in Rome.” Flaminia Gennari Santori, Director of the Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica, Rome: “We are delighted to present our museum and a part of our collection in Potsdam, a city with so many points of contact with the art and architecture of Rome.”

Pietro da Cortona (1596/7–1669), Virtues frame the Allegory of Divine Providence and present the papal tiara and the keys of Saint Peter’s, monumental ceiling fresco from the Gran Salone of the Palazzo Barberini.

Pietro da Cortona’s monumental ceiling fresco from the Gran Salone of the Palazzo Barberini welcomes visitors to the Potsdam exhibition in form of a ceiling projection. The famous painting celebrates the power of the Barberini, one of the most important families in seventeenth-century Rome. Virtues frame the Allegory of Divine Providence and present the papal tiara and the keys of Saint Peter’s. The fresco was commissioned by Maffeo Barberini, a patron of poets and men of letters who, as a young man, had his portrait painted by Caravaggio. Even before his election to the Holy See in 1623, he had surrounded himself with writers and scholars, and begun assembling an art collection. As Pope Urban VIII, he became one of the leading art patrons and transformed Rome into the capital of the Baroque. During his pontificate, the basilica of Saint Peter was completed and consecrated. New streets and squares were created that continue to shape the face of the city today. In the Thirty Years’ War (1618–1848), Urban VIII did not support any of the warring factions, preferring instead to remain neutral and to pursue his dream of initiating a Golden Age of painting, architecture, literature and music that would rival the Renaissance. Yet his pontificate was marked by the rise of violent assertion of religious dogma, which led to the Roman Inquisition. Galileo, a friend of Urban VIII, was investigated by the Inquisition and forced to recant his teachings.

Caravaggio’s Narcissus

Caravaggio’s focus on the decisive moment of a narrative brought about a new kind of art. His chiaroscuro effects broke with all accepted norms and made him one of the pioneers of baroque painting. His work was controversial: while his supporters praised his daring stylistic innovations, his detractors disparaged him as disrespectful and as an anarchist out to destroy the time-honored values of painting. Among the many outstanding works coming to Potsdam is an early work by Caravaggio, his Narcissus (1597–1599). Ortrud Westheider: “Caravaggio shows a young man looking at his reflection—Narcissus, whose vain infatuation with himself was his undoing. The painting is famous for its focus on the dramatic turning point. Its modernity, the way in which the painted image reflects the power and potential of painting, has lost none of its fascination.”

Caravaggio (1571-1610), Narcissus, 1598/99. © Photo: Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica di Roma – Bibliotheca Hertziana, Istituto Max Planck per la storia dell’arte / Mauro Coen.

Violence and Salvation: Caravaggio and his Circle

Coinciding with the Counter-Reformation and religious wars across Europe, Caravaggio’s realism hit a nerve. The crusade against Protestantism, condemned as heretical, encouraged a new form of fervent piety and religious mysticism that is evident in Orazio Gentileschi’s emotionally charged painting Saint Francis Supported by an Angel (ca. 1612). At the same time, paintings like Giovanni Baglione’s Sacred and Profane Love (before 1603) testify to the violence of the period and to a new self-confidence on the part of the artists who responded to the tension between the artistic sophistication and strict clericalism of early seventeenth-century Rome.

Orazio Gentileschi, Saint Francis supported by an angel (San Francesco sorretto da un angelo), c.1605–07, © Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica.

Giovanni Baglione (1566-1644), Sacred and Profane Love, 1602, © Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica.

Like Caravaggio, the artists in his circle studied models who came from the poorest parts of Rome. This practice invested the monumental altarpieces and paintings of saints with an unprecedented poignancy. Devotional images came to life and were reinterpreted as scenes of everyday life. Thus Carlo Saraceni, another contemporary of Caravaggio, presents us with an unhappy Christ Child in his unglamorously domestic Madonna and Child with Saint Anne (ca. 1611).

Dramas of the Demimonde: The Caravaggisti in Naples

His involvement in a fatal brawl drove Caravaggio to flee Rome for Naples, then under Spanish rule. His style inspired numerous local artists. Luca Giordano and Battistello Caracciolo adopted not only his close focus and the monumentalization of his figures but also experimented with his dramatic lighting. They updated the stories of ancient philosophers and Christian saints and followed Caravaggio’s lead in presenting the historical events as if they unfolded on a stage. In Venus and Adonis (1637), Jusepe de Ribera chose the dramatic moment in which Venus lays eyes on her mortally wounded lover. The Spanish-born painter, who had seen Caravaggio’s works in Rome in 1615, admired his sense of drama and his consummate handling of implicit and explicit violence.

Jusepe de Ribera (1591-1652), Venus and Adonis, 1637, © Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica.

Light and Shadow: The Caravaggisti in Northern Europe

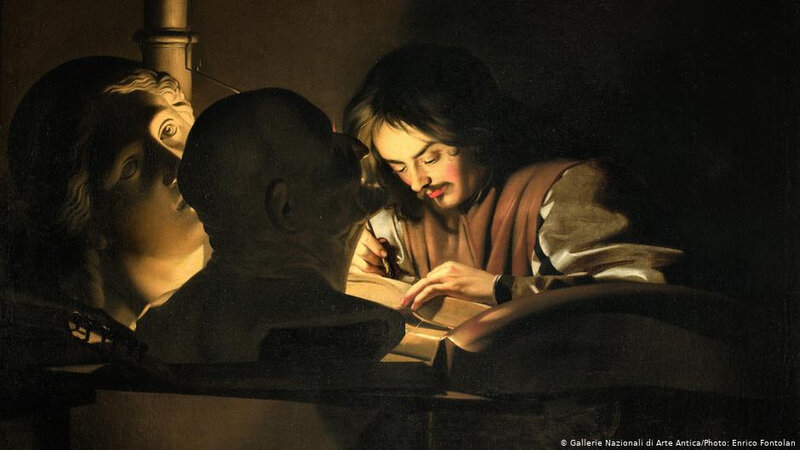

Painters from Flanders and France brought their artistic conventions to Rome and drew on the classically inspired style shaped by Raphael and Michelangelo. Simon Vouet and Matthias Stom adopted the strikingly lit interiors and nocturnal scenes popularized by Caravaggio and his circle. Their own treatment of light and shade—often symbolizing good and bad—became a new, highly specialized form of art that met with great acclaim in their home countries. Michael Sweerts’s The Artist at Work (mid-seventeenth century) similarly follows the chiaroscuro trend, but also mirrors the controversy about the competing styles of Caravaggio and Guido Reni, who had died in 1610 and 1642 respectively. Was art to depict reality, as Caravaggio contended, or was it, as Reni held, to emulate classical models and ideals? Playing with these opposing points of view, Sweerts defied the dogmas of the generations of artists before him.

Matthias Stom (ca. 1600-1652), Samson and Delilah, © Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica. Photo: Enrico Fontolan

Michael Sweerts (1618-1664), The artist in his studio, mid 17th century, © Gallerie Nazionali di Arte Antica. Photo: Enrico Fontolan

Allegories of the Arts: German Collector Preferences

The Grand Tour, an educational journey which included an extensive sojourn in Italy and focused on antiquity, art and architecture, was an obligatory rite of passage for young European aristocrats. By the eighteenth century, private collections, like that of the Barberini, began to form an increasingly important part of the itinerary. For German princes, they became a model of their own collecting ambitions. They looked for classical subjects and had a penchant for allegories of the arts, epitomized in Rome by the work of Simon Vouet, Salvator Rosa, and Prospero Muti. The female figure holding a palette and paintbrush in Simon Vouet’s Allegory of Painting (Self-portrait) of the early 1620s is probably a portrait of Artemisia Gentileschi, the most famous female painter of the period. The exhibition presents two works by her from the collection of the Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg (Prussian Palaces and Gardens Foundation Berlin Brandenburg).

Gallery of Foolishness: Italian Baroque Paintings in the New Palace in Potsdam

On loan from the Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg, the two paintings, Lucretia and Sextus Tarquinius (ca. 1630) and David and Bathsheba (ca. 1635), leave the New Palace in Potsdam for the first time in 250 years to exemplify the influence of Roman baroque painting on German collections. When Frederick II (Frederick the Great), King of Prussia, acquired the paintings for the New Palace, he did not know that they had been painted by a woman. In 1769 he set up an Italian gallery with works by Giordano Bruni and Guido Reni as well as the two paintings now attributed to Artemisia Gentileschi. With its emphasis on biblical and mythological subjects, the gallery explored the disastrous consequences of male desire. The Prussian king, whose Sanssouci Palace, Ruinenberg and Barberini Palace drew on imperial as well as bucolic models, confronted his successor, Frederick William II, with this “Gallery of Foolishness.”

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593-1653), Bathseba at Her Bath. © SPK. Photo: Daniel Lindner

Palazzo Barberini: The Architectural Model for the Museum Barberini in Potsdam

The Museum Barberini was named after the Barberini Palace, built by Frederick the Great in central Potsdam. Destroyed in the Second World War, it was reconstructed as a modern museum on the original site by the Hasso Plattner Foundation between 2013 and 2016. The Prussian king, Frederick the Great, wanted an Italian piazza in Potsdam and found inspiration in an engraving of the Palazzo Barberini in Rome by Giambattista Piranesi. With this reference to Pope Urban VIII, a great patron of the arts, Frederick II laid claim to being an equally astute collector and connoisseur of art. Frederick and his successor, Frederick William II, commissioned numerous Italianate buildings in Potsdam.

Museum Barberini as a Starting Point for an Exploration of Italy in Potsdam

Complementing the exhibition Baroque Pathways, the Museum Barberini invites visitors to explore the Italian influence on Potsdam’s cityscape. The audio tour Italy in Potsdam on the Barberini App directs visitors to 30 Italianate buildings and works of art of the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Available in three languages (German, English and Italian), the self-guided city tour draws intriguing visual comparisons between Potsdam and Italy.

To mark the exhibition Baroque Pathways, the Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg, the city of Potsdam and the Museum Barberini are turning the summer of 2019 into a citywide celebration of Italian art and culture. Guided tours, concerts, talks, film screenings, an open night at the Potsdam palaces, and many other events show Potsdam at it most Italianate.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F68%2F37%2F119589%2F128313729_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F15%2F78%2F119589%2F127923120_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F60%2F42%2F119589%2F122236959_o.jpeg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F90%2F14%2F119589%2F117943406_o.jpg)