Bonhams to offer 8 museum-quality sculptures from one of the most important Himalayan art collections

Lot 805. A Gilt Copper Alloy Figure of Manjushri, Nepal, 9th-10th Century. Himalayan Art Resources item no.68446; 37.7 cm (14 7/8 in.) high. Estimate: HK$ 20,000,000 - 25,000,000 (€ 2,300,000 - 2,900,000). Photo: Bonhams.

HONG KONG.- The international auction house Bonhams will present ‘The Path of Compassion: Masterpieces of Buddhist Sculpture’ on 7 October in Hong Kong – a single owner sale of eight Buddhist sculptures from the esteemed Nyingjei Lam Collection.

The Collection, which translates into ‘Paths of Compassion’, is long regarded as the gold standard in the field of collecting Himalayan Art, comprising outstanding examples of Tibetan sculpture as well as superb works from surrounding regions that were important in the formation of Tibetan sculpture: eastern India, Swat Valley and Nepal.

The eight works on offer – all fresh to the market – were previously on long-term loan for more than ten years to the Rubin Museum of Art, New York. Spanning a millennium from seventh century Nepal to 17th century Tibet, these museum-quality sculptures are immediately magnetic in their beauty and presence, each representing the very best of its own types.

Edward Wilkinson, Bonhams’ Global Head of the Indian, Himalayan, and Southeast Asian Art and Executive Director, Asia, commented: ‘It is a truly rare occasion that eight Buddhist sculptures of this preeminent quality are available in the market at once. We are honoured to be entrusted with this collection, which is a testament to Bonhams’ dedication to the field of Himalayan Art as a defined category.’

Leading the sale is A Gilt Copper Figure of Bodhisattva Nepal, circa 9th Century, noted for his commanding presence with a facial expression of empyrean authority and transcendent stillness. Belonging to a very small group of large-scale sculptures from the early Nepalese tradition, he is seated in an unusual relaxed position holding a single jewel in his raised right hand. The surface has been worn smooth from centuries of ritual worship and retains a glossy smooth patina. The traces of blue pigment in the hair is indicative of the sculpture having been transferred and preserved in Tibet.

The collector, who is a Roman Catholic of Irish-American origin but was based in Asia for almost half a century, began to form this collection after encountering the compassionate smiles that radiated from the faces of many of the statues of Buddhas, Bodhisattvas, saints and lamas. Over his collecting journey, the collector discovered that in Buddhism the path to true freedom and happiness is both love and compassion – just as in his faith in Christianity.

Proceeds from this sale will go to support the Nyingjei Lam Trust’s mission of education and social projects in India and other regions around the globe.

Lot 805. A Gilt Copper Alloy Figure of Manjushri, Nepal, 9th-10th Century. Himalayan Art Resources item no.68446; 37.7 cm (14 7/8 in.) high. Estimate: HK$ 20,000,000 - 25,000,000 (€ 2,300,000 - 2,900,000). Photo: Bonhams.

Published: David Weldon and Jane Casey Singer, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, London, 1999, pp.88-9, pl.11.

Karl Debreczeny, "Wutai Shan: Pilgrimage to Five-Peak Mountain", in Journal of the International Association of Tibetan Studies, issue 6 (December 2011), p.72, cat.20.

Franco Ricca, Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Turin, 2004, fig.IV.11.

Exhibited: Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Palazzo Bricherasio, Turin, 18 June – 19 September 2004.

Wutaishan: Pilgrimage to Five Peak Mountain, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 10 May 2007 – 16 October 2007.

Casting the Divine: Sculptures of the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2 March 2012 – 11 February 2013.

Provenance: The Nyingjei Lam Collection

On loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1996-2005

On loan to the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2005-2019.

Note: Manjushri, the Great Bodhisattva of Perfected Wisdom, sits with his legs in a relaxed posture commonly translated as 'royal ease' (rajalilasana), but his upright torso, broad shoulders, and immutable countenance suggest he is indefatigably in pursuit of the Dharma. Held between his right thumb and forefinger, the bodhisattva possesses a seed, or perhaps a wish-fulfilling gem (cintamani), one of seven precious attributes a chakravartin (lit. "wheel-turner") uses to administer a fair and just empire. He rests his other hand on his left knee, and the hint of a joint on the little finger suggests a possible anchor previously used to affix a separately cast lotus stem. Hanging against his strong pectorals is a necklace with pendant tiger claws that identifies Manjushri. Prominent regalia wrap around his arms and crown his head, framing his noble and resolute expression.

This majestic sculpture is a leading example of a distinguished group made by Newari master craftsmen recognized by scholars to be some of the earliest Buddhist bronzes produced for Tibetans. Their dating has been debated, with some believing they belong to the Tibetan Empire and its aftermath between the 9th and 10th centuries, while others see them as products of the subsequent period, namely the Second Diffusion of Buddhism in Tibet from the late 10th to 12th centuries. (For example, see Pal,Himalayas: An Aesthetic Adventure, Chicago, 2003, p.28; and von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculpture in Tibet, Vol.II, Hong Kong, 2003, p.914; respectively). However, mounting research into Buddhist art and religion of the Tibetan Empire indicates that this earlier context is more appropriate, thus positioning this bronze among the most important surviving Buddhist sculptures of a period when Tibetans burst onto the world stage as the greatest military rivals of the Tang Empire.

Many sculptures from this early group, located within monastic repositories in Lhasa, Tibet, have been published by von Schroeder (Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, Vol.II, Hong Kong, 2003, pp.930-40, nos.216A-221A). They share a common treatment of regalia, garments, facial types, and metallic composition. Published elsewhere, two other bronzes of bodhisattvas match the present lot's height (approx. 37 cm): one of Vajrapani in the Pritzker Collection (fig.1), the other of an unidentified bodhisattva in the Tibet Museum, Lhasa (Tianlu Wenhua: Tibetan History and Culture, Beijing, 2018, pp.74-5). They are only bested in size by a sculpture of Amitayus, at 46 cm high, held in a monastery in Bhutan (Bartholomew & Johnston (eds.), The Dragon's Gift, Chicago, 2008, p.166, no.9). Yet being of superior quality and scale than most, the present sculpture of Manjushri is one of the leading examples of the group.

Fig.1. Gilt Copper Alloy Seated Vajrapani, Nepal or Tibet, late Tubo period, 9th-10th century, 37 cm (14 1/2 in.) high, Pritzker Collection, Chicago. Image Courtesy Pritzker Art Collaborative.

Newari proclivities and craftsmanship are clear throughout the sculpture. As seen in sculptures produced for worship in Nepal, Newars made use of their homeland's large deposits of copper to produce heavy, almost solidly cast, sculptures of a rich dark brown color. The present sculpture's elegantly proportioned limbs, convincing sense of balance and weight, and sensuous modelling of the waist are also rooted in the sculptural traditions of Nepal. Whereas it has been suggested this bodhisattva's tall crown represents a departure from Nepalese sculpture, the same proportions (about 1.25x the height of the face) are seen in 9th- and 10th-century examples, such as a c.800 stone stele of Avalokiteshvara at Chabahil Stupa in Kathmandu (Pal, The Arts of Nepal, Leiden, 1974, fig.187) and a 10th-century Nepalese bronze of Avalokiteshvara in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig.2; 1982.220.14; see a second in 1988.282).

Fig.2. A Copper Alloy Figure of Avalokiteshvara, Nepal (Kathmandu Valley), 10th century, Thakuri period, 33.6 cm (13 1/4 in.) high, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Accession Number 1982.220.14.

Yet certain stylistic elements in this sculpture distinguish it from those typically made by Newaris for worship in Nepal. Its spired armbands are different, its modelling is more hieratic, its tone more authoritative. Because most known examples of the broader stylistic group have survived in Tibet, and some bear Tibetan inscriptions (including lot 804 in this sale), scholars infer that Newar master craftsmen produced these objects for Tibetan patrons. Records of Newari ateliers working in Tibet on architectural decoration date as far back as the 7th century, with the building of the Johkang in Lhasa, the Tibetan Empire's seat of power, and the creation of Tibet's first Buddhist monastery, Samye, in the 8th century. However, these bronzes, far more portable than the materials, conditions, and infrastructure required to cast them, were likely produced and dispatched from preexisting foundries in Nepal.

When concluding their previous publication of this bronze, Weldon and Casey Singer suggest the unlikelihood that a commission of its scale and importance would have been produced earlier than the 11th century, because of the persecution of Buddhist communities in Tibet after the fall of the Tibetan Empire in the mid 9th century. However, more recent research into this period suggests that Eastern Tibet provided a refuge from such persecution and became a center of Buddhist propagation by the 10th century (Xie, "Tibetan Buddhism and Tibetan Buddhist Art in the Xixia Kingdom", in Debreczeny (ed.), Faith and Empire, New York, 2019, p.83). Moreover, 9th-century Buddhist artefacts from the Tibetan Empire demonstrate stylistic precedents for these sculptures, suggesting that their dating should be closer in proximity.

Stylistic elements of Buddhist art produced under the Tibetan Empire include broad shoulders, narrow waists, and large spired jewelry—key elements also distinguishing the present bronze from Nepalese sculpture (Debreczeny (ed.), Faith and Empire, New York, 2019, p.20). Sharing these features are Drak Lhamo, Bimda Temple, and Denma Drak, three large-scale rock carvings from the Tibetan Empire in Eastern Tibet dated by inscription to the late 8th and early 9th centuries (studied in Heller, "Eight- and Ninth-Century Temples & Rock Carvings of Eastern Tibet", in Casey Singer & Denwood (eds), Tibetan Art: Towards a Definition of Style, London, 1997, pp.86-103).

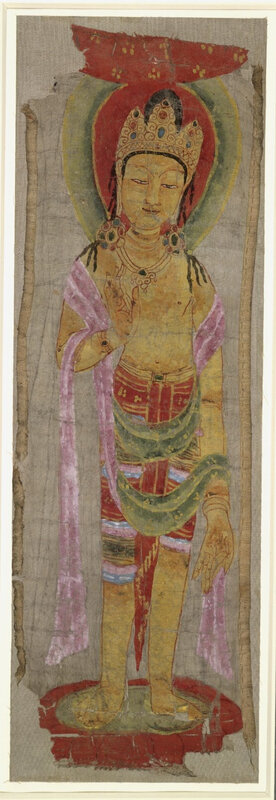

At the height of its power, the Tibetan Empire controlled large portions of the Hexi Corridor in Gansu province, China, including Dunhuang, which was a thriving center of Buddhist activity along the Silk Road. The artefacts produced at Dunhuang and its environs under Tibetan occupation between 787-848 CE also show a basis for the present sculpture and its broader stylistic group. For example, a 9th-century temple banner of a bodhisattva, now in the British Museum, exhibits a similar crown, earrings, facial type, and tresses (fig.3; 1919,0101,0.101).

Fig.3. A Bodhisattva Banner from Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, Dunhuang, Tang, 9th century, 44.5 x 14.5 cm. Paint on silk, The British Museum, London, Registration Number 1919,0101,0.101. © The Trustees of the British Museum

A mural at the back wall of Yulin Cave 25 depicting the iconographic program of Vairocana and The Eight Great Bodhisattvas (fig.4) is one of the best examples of the style of Buddhist art patronized by the Tibetan Empire in the 9th century. The present Manjushri clearly approximates the central Vairocana's physiognomy, garments, and regalia, while its seated posture mirrors that of the extant bodhisattvas. Manjushri is one of the Eight Great Bodhisattvas and both the Pritzker Vajrapani and the Tibet Museum bodhisattva are consistent with this program. The theme of Vairocana and The Eight Great Bodhisattvas promulgated a claim that the Tibetan emperor was a divinely sanctioned chakravartin ('universal monarch') engaged in a bid to spread Buddhism and devoutly rule the world (Debreczeny (ed.), op. cit., p.25). This iconographic program is so prevalent in the Tibetan Empire that it prompts us to consider the likelihood that this regal sculpture of Manjushri was once part of a set dedicated to this theme, and thus intricately linked to the emperor.

Fig.4. Mural of Vairocana and the Eight Great Bodhisattvas, Yulin Grottoes Cave 025, High Tang Dynasty, c.713-766. Image Produced by Cultural Relics Digitization Institute. Image Courtesy of Dunhuang Academy.

The popularity of this theme in Tibet predated the 11th century, since tantras relating to Vairocana and The Eight Great Bodhisattvas were among a number that were eventually replaced by the Highest Yoga Tantra traditions (Anuttarayoga Tantra) during the Second Diffusion of Buddhism. Recent years have witnessed increased interest in this early period of Tibetan history, with two landmark exhibitions closely examining the material culture and religion of the Tibetan Empire: Faith and Empire: Art and Politics in Tibetan Buddhism at the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, and Cultural Exchange Along the Silk Road: Masterpieces of the Tubo Period (7th – 9th Century) at the Dunhuang Academy Exhibition Center, Dunhuang (publication forthcoming 2020). Stylistic evidence suggests that this sculpture was most likely produced by Newar craftsmen for Tibetan patrons in the 9th and 10th centuries, tying together Buddhist devotion and ideals of statecraft. It would follow that this magnificent image of Manjushri is among the most important sculptures predating the Second Diffusion of Buddhism, and one of the earliest surviving Buddhist bronzes from Tibet.

Bonhams would like to thank David Pritzker for his assistance with the preparation of this lot.

Other Highlights Include:

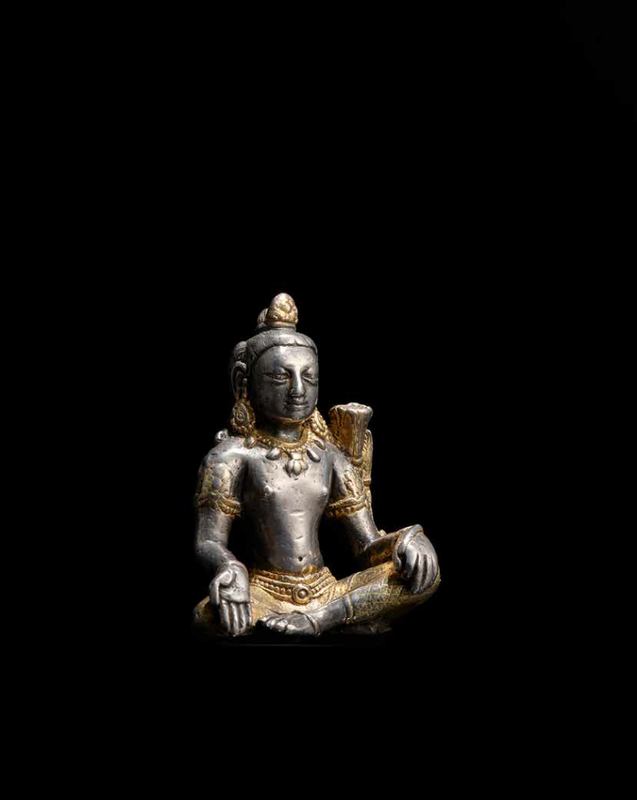

Lot 801. A Silver Inlaid Copper Alloy Figure of Avalokitesvara, Swat Valley, circa 7th Century. Himalayan Art Resources item no.68412; 12.6 cm (5 in.), height of figure, 16 cm (6 1/4 in.), height including mandorla. Estimate: HK$ 1,600,000 - 2,000,000 (€ 190,000 - 230,000). Photo: Bonhams.

With its original, separately-cast backplate, and a single line inscription on the back of the figure's cushion, probably reflecting the donor's name: "vajrasiṅa".

Published: David Weldon and Jane Casey Singer, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, London, 1999, p.36-7, pl.2.

Franco Ricca, Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Turin, 2004, fig.IV.2.

Exhibited:The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 6 October – 30 December 1999.

Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Palazzo Bricherasio, Turin, 18 June – 19 September 2004.

Female Buddhas of Enlightenment in Tibetan Mysticism, Bruce Museum of Art, Greenwich, 2 July 2005 – 16 October 2005.

Casting the Divine: Sculptures of the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2 March 2012 – 11 February 2013.

Provenance: The Nyingjei Lam Collection

On loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1996-2005

On loan to the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2005-2019.

Note: The bronze shows Mahabodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, 'The Lord of Compassion', relaxed above a wicker stool with a jaunty expression enlivened by silver inlay. As if animate, he leans to one side, raising his right index finger towards his temple in a pensive gesture. A lotus flower rises from his left hand, while another protects the sole of his left foot from touching the profane world.

The bronze's creator, a master likely working around the turn of the 6th and 7th centuries, labored over the bodhisattva's modelling, detailing contours of a lithe physique to evoke a young and capable savior. The artist wrapped the bodhisattva's athletic hips in a light lower garment that twists and pools with sumptuous pleats. His creation has survived unspoiled to this day, retaining its fine detail with a smooth rich brown patina of red and green inclusions.

Behind Avalokiteshvara, on a separately cast mandorla, two attendants rejoice in the bodhisattva's presence. They flank his flaming halo, surmounted by a mahaparinirvana stupa, a symbol of the transcendental 'buddha-nature' benevolently permeating our world. Given the precise positioning of the attendants behind Avalokiteshvara's shoulders, the mandorla appears to be original to the piece. It is also stylistically consistent with a handful of other surviving examples from the period (e.g. Klimburg-Salter, The Silk Route and the Diamond Path, Los Angeles, 1982, pl.7; Rossi & Rossi Ltd, Gods and Demons of the Himalayas, London, 2012, no.7; Sotheby's, New York, 26 March 2003, lot 15). In all manner of subject, dating, quality, and condition, the present lot is one of the most exceptional early Buddhist bronzes from the Swat Valley.

Nestled in the foothills of the Hindu Kush mountain range, at the crossroads of the Indian Subcontinent and Central Asia, Swat Valley was an important locus within the development and spread of Buddhist traditions between India, the Western Himalayas, and East Asia. Swat Valley's small corpus of bronzes shows an intriguing synthesis of aesthetic modes from the art of the Kushans, Guptas, and Sasanians: powerful empires who once wielded influence over the region. These bronzes also exhibit exciting precedents for the artistic schools of Kashmir, Gilgit, and Guge.

It is among Swat Valley bronzes that we see some of the earliest depictions of important Mahayana and Vajrayana deities connecting Swat with the broader Buddhist world. For example, the pensive posture adopted by this bronze is also seen throughout Buddhist sculpture of China and Korea between the 5th and 7th centuries. This includes some of Korea's great national treasures, such as National Treasure 83, a late 6th-/early 7th-century gilt bronze Pensive Bodhisattva in the National Museum of Korea (fig.1; Deoksu 3312), which is contemporaneous to the present lot.

Fig.1. Pensive Bodhisattva, Three Kingdoms Period, Gilt Bronze, 93.5 cm high, National Treasure 83, National Museum of Korea, Accession Number Deoksu 3312.

This bronze's rather unique reticulated base continues an iconographic tradition in early Mahayana art of depicting bodhisattvas seated on wicker stools (as opposed to lotus thrones, reserved for buddhas). Among the most important remaining Gandharan sculptures, the Mohammed Nari Stele shows a host of bodhisattvas seated on wicker stools of various designs, including two pensive bodhisattvas by the top center (Luczanits (ed.), The Buddhist Heritage of Pakistan, New York, 2011, p.163, no.68).

There are only a few other Swat bronzes that go so far as to perforate the base to depict the basketry weave realistically, although neither as decoratively as the present lot. These include a c.6th-century Pensive Avalokiteshvara in the Alain Bordier Foundation and a 8th-/9th-century bronze of the same in the Palace Museum, Beijing (see von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculptures of the Alain Bordier Foundation, Hong Kong, 2010, p.11, pl.2A; & Zangchuan fojiao zaoxiang, Hong Kong, 2008, no.7; respectively). Most others merely echo the iconography with chased patterns, such as examples in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig.2; 1974.273); Asia Society, New York (1993.2); and the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford (EA1971.14). Neither do they portray Avalokiteshvara's physique and garments with the same level of sophisticated modelling and meticulous detail. The present lot truly stands out as a rare and refined Swat bronze.

Fig.2. Avalokiteshvara Padmapani, 7th century, Pakistan (Swat Valley). Bronze inlaid with silver and copper, 22.2 cm (8 3/4 in.) high, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Accession Number:1974.273.

Lot 803. A Brass Shrine to Canda Vajrapani, Tibet, circa 12th-13th century. Himalayan Art Resources item no.68451; 18.5 cm (7 1/4 in.) high. Estimate: HK$2,000,000 - 3,000,000 (€ 230,000 - 350,000). Photo: Bonhams.

Published: David Weldon and Jane Casey Singer, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, London, 1999, pp.98-9, pl.16.

Franco Ricca, Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Turin, 2004, fig. IV.25.

Exhibited: The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 6 October – 30 December 1999.

Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Palazzo Bricherasio, Turin, 18 June – 19 September 2004.

Casting the Divine: Sculptures of the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2 March 2012 – 11 February 2013.

Provenance: The Nyingjei Lam Collection

On loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1996-2005

On loan to the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2005-2019.

Note: A most ancient deity, Vajrapani, 'holder of the thunderbolt', is believed to have evolved from the Indian Vedic god Indra, who is evoked as 'The King of Heaven' and 'The Bringer of Rains'. Throughout history Vajrapani has assumed various roles, including that of a supportive yaksha, a protector deity, and a manifestation of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara. As the foremost guardian of Buddhism, a good number of sculptures depicting Vajrapani have survived, among which the present work is one of the rarest and most remarkable early examples.

With elephants and lions underfoot, a tiger skin around his waist, and snakes for jewelry, Vajrapani is depicted as a terrific guardian able to subdue the most dangerous of creatures. This is all the more heightened by his biting a snake and imbibing its poison. Framed by a distinctive flaming mandorla, with the sun and moon flanking his head, the sculptor has produced a spirited divine bodyguard projecting an air of implacable power.

Many special iconographic features speak to the uniqueness of this commission, among which his left hand gesture is the most notable. Normally Vajrapani in his two-armed wrathful form would either raise his left hand in front of his chest in karana mudra or hold a bell or lasso, but here his left hand points sideways in tarjani mudra. While no other example of the same exact iconographical compilation is known, two other early works show Vajrapani with the similarly pointing hand gesture. One is a 12th-century painting at the Rubin Museum of Art (C2002.11.2, HAR 65088). The other is an 11th-century bronze in the same collection (HAR 65566). The prominent striding figure embedded within this sculpture of Vajrapani's hair likely represents Samvara or Vajrahumkara, and is another highly unusual detail rarely seen in other images of Vajrapani. So are the two large severed heads suspended below his arms from either side of the prabhamandala.

Stylistically, the influence of the Pala sculptural tradition is evident in the treatment of the sculpture's necklace, sashes, and lotus petals. The rectangular throne with a projecting central section is also clearly inspired by earlier examples from Northeastern India. For instance, a 10th-century Pala blackstone stele of Vajrapani in the Victoria and Albert Museum (IM.2-1932) shares a similar three-sectioned pedestal with decorative motifs.

A close stylistic parallel to this bronze is that of a multi-armed deity preserved in the Jokhang Monastery in Lhasa (fig.1; von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, Vol.II, Hong Kong, 2003, pp.1144-5, no.299D-E). Similar in size, the two sculptures share the same pointy hair bun, wide nose, lip-biting fangs, crown flowers, and tiger skin patterns. Both figures have the same double-line treatment under the chest, likely there to exaggerate the deity's volume. Both bases follow the three-sectioned Pala model and are decorated with almost identical eight-point star symbols representing the dharma wheel.

Fig.1. A brass alloy figure of a multi-armed deity, Tibet, 14th century [sic], 17 cm high. After Ulrich von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, Vol.II, Hong Kong, 2003, pp.1144-5, no.299D-E

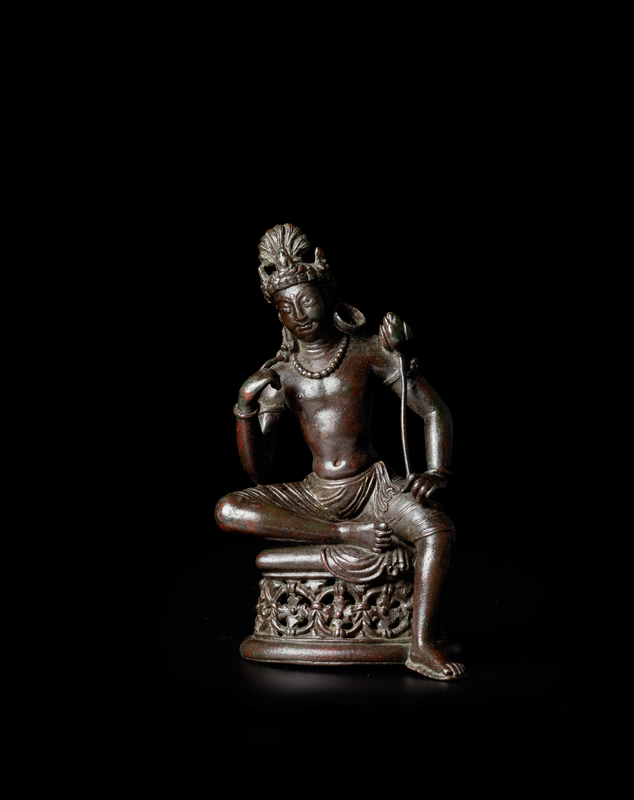

Lot 806. A Copper Alloy Figure of Jambhala, Tibet, circa 13th-14th century. Himalayan Art Resources item no.68453; 21.6 cm (8 1/2 in.) high. Estimate: HK$2,400,000 - 2,800,000 (€ 280,000 - 320,000). Photo: Bonhams.

Published: David Weldon and Jane Casey Singer, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, London, 1999, pp.102-3, pl.18.

Franco Ricca, Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Turin, 2004, fig. IV.32.

Exhibited: The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 6 October – 30 December 1999.

Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Palazzo Bricherasio, Turin, 18 June - 19 September 2004.

Casting the Divine: Sculptures of the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2 March 2012 – 11 February 2013.

Provenance: The Nyingjei Lam Collection

On loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1996-2005

On loan to the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2005-2019.

Note: Primarily known as the God of Wealth, Jambhala is one of the most popularly worshipped deities in Tibetan Buddhism, propitiated in order to avoid the mundane distractions of ensuring sustenance so that practitioners can focus on their spiritual training. Here, a skilled craftsman has represented the deity in his full, corpulent glory, symbolic of the abundance Jambhala is able to grant. Jambhala offers a bijapuraka fruit with his outstretched right hand, while his left massages the neck of a magical mongoose, prompting it to disgorge three strands of jewels from its plump belly. The deity rests his pendent right foot comfortably on the mouths of not one, but three money pots, while clad in resplendent jewelry indicative of the wealth they store. With these delightful details, the master hand has produced a vision of Jambhala with wide-opened eyes and a faint smile—appearing alert and engaged—a reminder of the deity's imminent presence to the mortal realm.

This bronze's sculptor was clearly well-versed in idioms of an earlier artistic tradition from Northeastern India under the Pala Empire (8th-12th centuries). Various elements reflect Indian prototypes, including the tall chignon, the crown's projecting side ribbons, the jewelry design, and the base's beaded rims. A Pala stone stele of Jambhala in the Dallas Museum of Art (fig.1; 1995.78) clearly demonstrates the artist's familiarity. The present lot shares many stylistic details, such as the well-padded and defined hands, the large hoop earrings, and the round wealth pots under the right foot.

Fig.1. Jambhala, India, 800-1199. Black phyllite 59.69 x 26.99 x 10.16 cm (23 1/2 x 10 5/8 x 4 in.), Dallas Museum of Art, Gift of David T. Owsley via the Alconda-Owsley Foundation, Object Number 1995.78.

Meanwhile, other aspects betray Tibetan characteristics, such as the structural bars left interlacing the sculpture's tall crown leaves, and its base's plump and flattened lotus petals, both frequented throughout early Tibetan bronzes of the 13th and 14th centuries. This combination of stylistic elements exemplifies Tibetan artist's close apprenticeship of Pala art during and shortly after the Second Transmission of Buddhism from India to Tibet, known as the Chidar (late 10th-12th centuries).

Of almost identical size, a closely related sculpture of Jambhala is held in the Norton Simon Museum (M.1975.14.06.S). Like the present sculpture, it shows the deity wearing a prominent garland of blue lotuses secured by a jeweled clasp in his lap and holding a bijapuraka fruit of similar three-lobed design, as if partially peeled. The outstretched neck of the mongoose is also treated similarly. However, as one of the best iterations of Jambhala in this early Tibetan style—and therefore, of its scale, one of the best bronzes of any subject in this style—the current lot compares favourably to the Norton Simon example, displaying more movement and naturalism, and more refined detail.

Lot 807. A Silver Figure of Mahapratisara, Tibet, circa 17th century. Himalayan Art Resources item no.68464; 11.1 cm (4 3/8 in.) high. Estimate: HK$1.2–1.6 million. Photo: Bonhams.

With separately cast and affixed side ribbons and halo, the halo with remains of cold gold pigment.

Published: David Weldon and Jane Casey Singer, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, London, 1999, pp.124-5, pl.29.

Franco Ricca, Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell’Himalaya, Turin, 2004, fig. IV.67.

Exhibited: The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 6 October – 30 December 1999.

Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell’Himalaya, Palazzo Bricherasio, Turin, 18 June - 19 September 2004.

Casting the Divine: Sculptures of the Nyingjei Lam Collection, RubinMuseum of Art, New York, 2 March 2012 – 11 February 2013.

Provenance: The Nyingjei Lam Collection

On loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1996-2005

On loan to the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2005-2019.

Note: This silver, gemlike figurine pays tribute to Mahapratisara, a prominent divine protector against illness and danger in Tibetan and Newari Buddhism, who is also propitiated for rebirth into heaven. She is described in the Pancarakshasutra as being the chief among five female guardian deities, known as the Pancha Raksha, havingthe broadest purview of concerns she offers protection from. Mahapratisara is also said in the Bhadrakalpavadana to have protected Buddha’s wife, Yasodhara, during her six-year long pregnancy, safely bringing Rahula into this world.

Mahapratisara may appear in various forms and can be yellow or white in color. Her depiction here, with four faces and eight arms, conforms to the Bari Gyatsa of Bari Lotsawa Rinchen Drag (1040-1112), an important treatise on the appearance of deities. The sculpture has been fortunate to survive with the goddess’ attributes intact, which also follow the Bari Gyatsa, showing Mahapratisara holding an axe, a bow, a trident, a lasso, a wheel, a vajra, an arrow, and a sword. Commanding this plentiful array of weapons, she guards her followers.

The accomplished creator of this sculpture has mastered the deity’s complex form and sophisticated jewelry. Mahapratisara’s many arms radiate elegantly and naturally, with those on her right slightly lower than the ones on her left, corresponding to the gentle sway of her torso. Each of her four faces has an introspective gaze and a faint smile, bearing an air of transcendence. Her celestial nature is furtheraccentuated by an elaborate crown of jewel-centered teardrop leaves, and a stylized halo, “painted gold in the Tibetan manner of delighting in the effect of contrasting colors” (Weldon & Casey Singer, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, London, 1999, p.124). Every element, from her attributes to her regalia, has been cast with precision and refinement.

Traditionally, silver in Tibet is rarer and considered more precious than gold, being spared for commissions deemed more costly, meritorious, and efficacious. Additionally, Weldon and Casey Singer have suggested the choice of silver may also connote Mahapratisara’s white appearance as she materializes in Pancha Raksha mandalas (ibid.).

While commissioned by a Tibetan patron, the sculpture carries stylistic elements consistent with Newari art of the 17th century. The halo, for example, bears close similarity to those in two Nepalese bronzes of the period surrounding the heads of Kumara and Ganesa (see Pal, Nepal: Where the Gods are Young, New York, 1975, pp.118-9, figs.89-90). The faces, each with a prominent nose above a delicate mouth, are also stylistically Nepalese, as is the sensuous depiction of her narrow waist and the fleshy curves about her navel. Compare the treatment of her face and waist to that of a Nepalese White Tara published in Kramrisch, The Art of Nepal, New York, 1964, p.52. A 17th-century parcel-gilt silver figure of Ushnishavijaya, with similar face, coiffure, and overall proportions is published in Grewenig & Rist (eds.), Buddha: 2000 Years of Buddhist Art, Völklingen, 2016, pp.350-1, no.148.

Lot 804. A Gilt Copper Figure of Vajrahumkara, Tibet or Nepal, circa 9th century. Himalayan Art Resources item no.68445; 31 cm (12 1/4 in.) high. Estimate: HK$ 8,000,000 - 12,000,000 (€ 920,000 - 1,400,000). Photo: Bonhams.

With a Tibetan inscription on the tang below the proper left foot, "'ba tsi ra hung ka ra", representing a transliteration of the Sanskrit Vajrahumkara.

Publised: David Weldon and Jane Casey Singer, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, London, 1999, pp.86-7, pl.10.

Pratapaditya Pal, Himalayas: An Aesthetic Adventure, Chicago, 2003, p.173, cat.113.

Franco Ricca, Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Turin, 2004, p.178, fig.IV.12.

Exhibited: The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 6 October – 30 December 1999.

Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Palazzo Bricherasio, Turin, 18 June – 19 September 2004.

Illumination: Photographs by Lynn Davis, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 6 April – 16 July 2007.

Casting the Divine: Sculptures of the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2 March 2012 – 11 February 2013.

Provenance: The Nyingjei Lam Collection

On loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1996-2005

On loan to the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2005-2019.

Note: This energetic sculpture is a striking example of iconographic ingenuity. The dramatic figure is identified by its inscription as the archaic tantric deity Vajrahumkara. He stands in a dramatic pose (pratyalidha) that signifies the throwing of projectile weapons, as he is certainly about to release the vajra brandished in his top right hand—an enduring symbol of Buddhism's ability to dispel ignorance. With his primary hands, Vajrahumkara appears to conflate the eponymous thunderbolt-sound gesture (vajrahumkara mudra), formed by crossing the wrists, with the warning gesture (tarjani mudra), formed by pointing index figures, in one of the most unique mudras seen in Buddhist art. His wrathful expression is not represented by the traditional grimace, but by one half of his mouth biting his lower lip while the other snarls—yet another unusual feature of this unique sculpture. Heavily cast in a manner that seems to further substantiate the figure's terrific power, this distinctive sculpture is one of the earliest and largest bronzes of Vajrayana Buddhism's rarest deities, absent from most collections.

The sculpture is thought to be among the earliest surviving bronzes produced for worship in Tibet. Its heavy, copper-rich casting and skilled sense of movement are hallmarks of Newari craftsmanship commissioned by Tibetan patrons. An ethnic group from the Kathmandu Valley in Nepal, Newars are master artisans of unparalleled skill, who were frequently employed for major artistic projects in Tibet from as early as the 7th century. The majority of sculptures forming the distinguished stylistic group this sculpture belongs to are located within monastic repositories in Lhasa. Von Schroeder has published a significant amount, including a closely related figure of Trailokyavijaya (von SchroderBuddhist Sculpture in Tibet, Vol. I, Hong Kong, 2003, p.511, no.166B; also see nos.147A-D, 149A-E, 152A-G; and Vol.II, pp.930-40, nos.216A-221A). Scholars have debated their dating, but more recent evidence suggests a range in date between the 9th and 10th centuries (see lot 805 for further discussion).

This powerful Vajrahumkara likely belonged to a sculptural mandala also featuring two other known wrathful deities cast to a similar scale. These are a figure of Manjushri Yamantaka in the Pritzker Collection (fig.1) and another wrathful manifestation of Manjushri, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig. 2; 1982.220.13). The three probably represent the best examples of wrathful deities from this early stylistic group.

Fig.1. A Gilt Copper Alloy Manjushri Yamantaka, Nepal or Tibet, late Tubo period, 9th-10th century, 37 cm (14 1/2 in.) high, Pritzker Collection, Chicago. Image Courtesy Pritzker Art Collaborative.

Fig.2. A Gilt Copper Alloy figure of Manjushri, Nepal (Kathmandu Valley), 10th century, Thakuri Period. With color and gold paint, 31.8 cm (12 1/2 in.) high, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Accession Number 1982.220.13.

Pal pointed to a possible source for the set being the Manjushri Namansangiti Tantra or and its related teachings. The Namansangiti is a pivotal early text first translated into Tibetan in the 8th century, and is associated with a number of mandalas dedicated to Manjushri and Vairocana (Huntington & Bangdel, The Circle of Bliss, Columbus, 2003, p.428). The Namansangiti positions Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Perfected Wisdom, as the central emanating force within the cosmos, and the Buddhist pantheon as various emanations. Verse 71, for example, reads, "Indestructibly violent with great delight, he [Manjushri] performs the Hum of Vajrahumkara." (Davidson, "The Litany of Names of Manjushri", in Strickmann (ed.), Tantric and Taoist Studies, Brussels, 1981, p.27.) This would help explain the three sculpture's common references to Manjushri; this figure of Vajrahumkara holds in his outstretched left hand a cylindrical object which likely represents either a pestle or a sutra in the form of a hand scroll, two attributes commonly associated with Manjushri. It would also account for the ministerial crown depicted above Vajrahumkara's formidable gaze, which features the Five Presiding Buddhas with Vairocana positioned at the summit. Vajrahumkara and similar esoteric wrathful deities feature prominently in the early Yoga Tantra tradition which includes the Namansangiti. As another indicator of the sculpture's dating, the Yoga Tantras were promoted in Tibet during the 8th and 10th century before their popularity was replaced in the 11th century by the Highest Yoga Tantras (Anuttarayoga Tantra) during the Second Diffusion of Buddhism.

Lot 802. A Gilt Copper Alloy Figure of Virupa, Tibet, 14th-15th century. Himalayan Art Resources item no.68491; 14 cm (5 1/2 in.) high. Estimate: HK$ 2,400,000 - 2,800,000 (€ 280,000 - 320,000). Photo: Bonhams.

Published: David Weldon and Jane Casey Singer, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, London, 1999, pp.176-7, pl.42.

Franco Ricca, Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Turin, 2004, p.195, fig.IV.44.

Exhibited: Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell'Himalaya, Palazzo Bricherasio, Turin, 18 June – 19 September 2004.

Casting the Divine: Sculptures of the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2 March 2012 – 11 February 2013.

Provenance: The Nyingjei Lam Collection

On loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1996-2005

On loan to the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2005-2019.

Note: Of its scale, this is one of the best cast gilt bronzes of Virupa, a beloved c.9th-century tantric master and legendary rascal. Depicting Virupa with his right arm raised up to the sky, the sculpture recalls the most amusing episode from the mahasiddha's life: when he stopped the movement of the sun to avoid settling a bar tab.

Virupa is a 'root guru' for the Sakya order of Tibetan Buddhism and the first mortal master of its lamdre teachings. The lamdre teachings are a potent tantric practice that can lead to enlightenment within a single lifetime. Once an abbot of Nalanda monastery, and after giving up on decades of unsuccessful attempts at the Chakrasamvara tantra, Virupa received the lamdre teachings directly from the deity Vajra Nairatmya. His subsequent antinomian rituals cost him his affiliation, as other members of the monastic hierarchy frowned upon his use of meat and alcohol. Banished from Nalanda, he wandered as an eccentric enlightened yogin, performing a number of miracles.

One of the details distinguishing this bronze's quality is the garland of modelled flowers draped over Virupa's body. The garland is ubiquitous among portraits of Virupa, symbolic of his ecstatic life in the wilderness. However, rather than being cast as part of the surface of his body, here it is modelled three-dimensionally resting around his shoulders (contrast with a Virupa sold at Bonhams, Hong Kong, 29 November 2016, lot 102). His finely articulated coiffure is yet another example of the superb craftmanship exhibited by this bronze, as are Virupa's carefully delineated teeth.

The bronze was most likely made by a Newari master craftsman working for a Tibetan patron. The beautifully proportioned and sensuously modeled body resembles contemporaneous works from the Newari tradition of Nepal, as does the separately cast flower garland. Elements indicating a Newar adapting his work for a Tibetan patron—aside from the obvious Sakya subject—include the thick flat rim of the base below a beaded border, common among Tibetan sculptures of the 15th century. As Weldon and Casey Singer have discussed, Newari artists, known for their skilled metal casting, were frequently hired by wealthy Tibetan patrons during the 14th-15th centuries—among them notably the Sakya order (The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet, London, 1999, p.176). Two closely related examples of Virupa, also likely Newari products for Tibetan patrons, are a gilt bronze sold at Bonhams, New York, 16 March 2015, lot 16 (fig.1), and a silver figure with gilt bronze base in the collection of the Museum Rietberg (2007.72), currently attributed to the Khasa Malla Kingdom spanning western Nepal and western Tibet.

Fig.1. A gilt copper alloy figure of Virupa, Tibet or Nepal, 14th century, 12.5 cm (4 7/8 in.) high, Bonhams, New York, 16 March 2015, lot 16.

The present bronze has also clearly been made within a period of refinement in Tibetan art inspired by cultural exchange with the Yuan and Early Ming courts of China. For example, the incised foliate scrolls decorating the meditation band around Virupa's waist and right shin are clearly inspired by Yuan textiles; they closely resemble the decorative patterns behind donor figures on a famed kesi Vajrabhairava mandala in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig.2; 1992.54). Similar designs are also reproduced on several sculptures attributed to the Yuan dynasty (Bigler, Before Yongle, Zurich, 2013, pp.84-95, nos.19-21). Moreover, the lotus base's plump scroll-tipped petals are redolent of bronzes from imperial Yongle workshops, many of which were sent as diplomatic gifts to the Sakya order's enclave in Gyantse.

Fig.2. A kesi Vajrabhairava mandala (detail), Yuan Dynasty, circa 1330-32, 245.5 x 209 cm (96 5/8 x 82 5/16 in.), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Accession Number 1992.54.

Lot 808. A parcel-gilt silver figure of Manjushri, Nepal, 9th-10th century. Himalayan Art Resources item no.68439; 6.5 cm (2 5/8 in.) high. Estimate: HK$1– 1.5 million. Photo: Bonhams.

Published: David Weldon and Jane Casey Singer, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet: Buddhist Art in the Nyingjei Lam Collection, London, 1999, p.70, fig.41.

Franco Ricca, Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell’Himalaya, Turin, 2004, fig. IV.9.

Exhibited: Arte Buddhista Tibetana: Dei e Demoni dell’Himalaya, Palazzo Bricherasio, Turin, 18 June – 19 September 2004.

Wutaishan: Pilgrimage to Five Peak Mountain, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 10 May 2007 – 16 October 2007.

Casting the Divine: Sculptures of the Nyingjei Lam Collection, Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2 March 2012 – 11 February 2013.

Provenance: The Nyingjei Lam Collection

On loan to the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, 1996-2005

On loan to the Rubin Museum of Art, New York, 2005-2019.

Note: Solidly cast in parcel-gilt silver, the weight and jewel-like quality of this diminutive sculpture conveys a much larger presence. The lower garment is meticulously incised and gilded, and the jewelry is well defined, striking a contrast with the bare and sensuous torso and limbs. Easily held in one’s hand, the sculpture is intimate and a joy to engage with, which explains its heavily rubbed surface from sustained propitiation, resulting in a desirable smooth patina.

The sculpture represents Manjushri, the Bodhisattva of Perfected Wisdom, in a rare form deriving from Mahayana Buddhist literature. Unlike his common, sword-brandishing iconography, Manjushri sits here in a relaxed posture with his right hand extended in the wishfulfilling gesture and his left holding a blue lotus in bloom by his left shoulder. Other diagnostic features include Manjushri’s youthfulness, tiger-tooth pendant necklace, and the three long tufts of hair—one on top of his head and two falling to his shoulders.

A close stylistic parallel is a larger copper alloy figure of Manjushri, attributed to 10th-century Nepal, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (fig.1; 1978.394.1). The copper Manjushri wears a comparable tigertooth necklace and holds an almost identical blue lotus in his left hand, but also has a seed or small fruit in his right hand which is no represented in the current work. The two also share a similar facial type of slightly chubby cheeks and well-defined pupils.

A copper alloy figure of Manjushri, 10th century, Nepal (Kathmandu Valley), 16.7 cm (6 9/16 in.) high,The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,Gift of Mr. and Mrs. A. Richard Benedek, 1978, Accession Number 1978.394.1.

Compare the lozenge-shaped patterns on his lower garment and the beaded belt with circular buckle with that of a Nepalese gilt bronze Avalokiteshvara in the Nyingjei Lam Collection (Weldon & Casey Singer, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet, London, 1999, p.68, fig.38). Also, refer to a 10th-century Nepalese standing Manjushri, with similar armbands, hair, jewelry, and decorative lozenges in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1982.220.13), helping to inform this rare figure’s 9th-10th-century date.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F74%2F94%2F119589%2F128705688_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F56%2F88%2F119589%2F127649882_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F41%2F75%2F119589%2F126978834_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F08%2F51%2F119589%2F126856859_o.jpg)