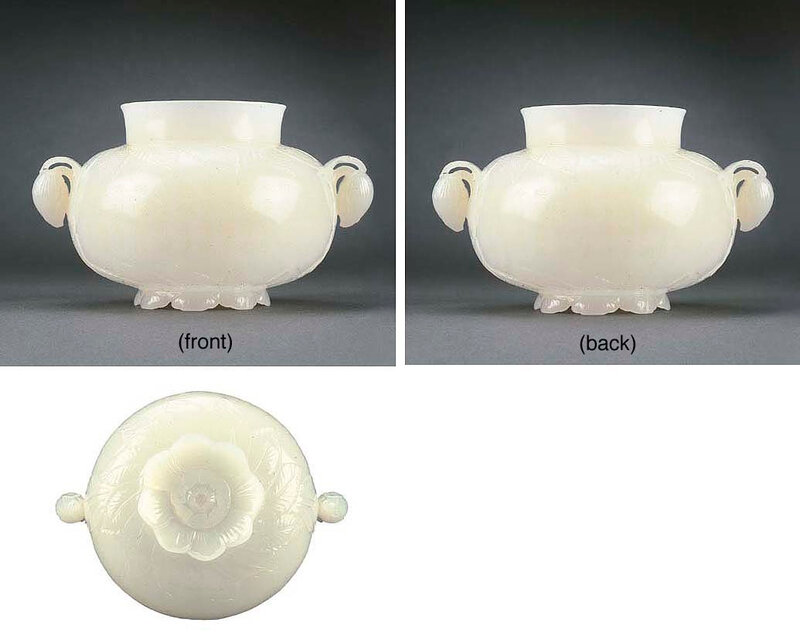

An exquisite imperial inscribed Mughal white jade jar, guan, Qianlong Guimao cyclical date, 1783 and of the period

Lot 54. An exquisite imperial inscribed Mughal white jade jar, guan, Qianlong Guimao cyclical date corresponding to 1783 and of the period; 5½ in. (14 cm.) wide. Estimate On Request. Price realised GBP 391,650. © Christie's Images Ltd 2002.

The body of compressed oval shape resting on a finely carved floral bloom, the edges of the petals gently curved to form the foot, encircled by overlapping leaves carved in shallow-relief radiating from the base and repeated on the shoulder, surrounding the short cylindrical neck, each side of the body with a pair of openwork handles carved as a down-turned floral bud growing from a stem, the body delicately incised with an inscription of standard script, ending with Qianlong guimao chun yuti, 'Imperial inscribed in the Spring of Qianlong guimao year', followed by a rectangular seal mark, Qingwan, 'pure pleasure', the highly translucent stone of a lustrous creamy white tone, one handle with minor chip.

Note: Perhaps the greatest Imperial collector in China's long history of artistic appreciation was the Emperor Qianlong (1736-95). One of his great passions was jade, and during his long reign he built up an unrivalled collection of works in this much revered material. Qianlong greatly admired archaic Chinese jades, but the contemporary jades for which he reserved his greatest praise were not Chinese, but those he termed 'Hindustan' (Hendusitan or Wendusitan) jades. Such was his fascination with these foreign jades that in AD 1768 he wrote a scholarly text, entitled Tianzhu wuyindu kao'e, on the geography of Hindustan and the derivation of its name. The area he identified was in what is now northern India centring on the city of Agra. In the eighteenth century this area was part of the Mughal Empire and thus the jades from this region are today often referred to as 'Mughal' jades. In fact some of the jades that have been classed by Qianlong as 'Hindustan' jades are of Turkish origin, but the majority of those taken into the Chinese imperial collection came from northern India. Such items came into China through trade but were also presented to the emperor as tribute gifts and gifts from Qing court officials, especially once the emperor's admiration of these jades became known.

Indeed these jades are so fine that in the past some scholars of Chinese art have felt that they could only have been made in China, for only in that country were there jade carvers of such extraordinary skill. Howard Hansford even offered as a possible explanation that Chinese jade carvers might have been invited to the Mughal court, and might have worked there, possibly even training Indian craftsmen ( S.H. Hansford, Chinese Carved Jades, Faber & Faber, London, 1968, p. 95). Robert Skelton has, however, convincingly argued that these beautiful pieces were indeed made by Indian lapidaries ('The Relations between the Chinese and Indian Jade Carving Traditions', The Westward Influence of the Chinese Arts, Colloquies on Art & Archaeology in Asia No. 3, Percival David Foundation, London, 1973, pp. 98-110). This is also the view taken by the researchers from the National Palace Museum, Taipei (Catalogue of a Special Exhibition of Hindustan Jade in the National Palace Museum, op. cit.).

These 'Mughal' jades were so highly regarded by the Qianlong Emperor that lapidaries working for the Chinese court were commissioned to make jade items in Mughal style. In 1983 the National Palace Museum, Taipei held a Special Exhibition of Hindustan Jade in the National Palace Museum. The well-researched catalogue that accompanied this exhibition provided a clear distinction between those jades of Indian origin, those of Turkish origin and those made in China (nos. 74-82 in the exhibition). While these Chinese jades in Hindustan style are exquisite, it is clear from the exhibited pieces and from the recorded comments made by the Qianlong Emperor that they never achieved the same remarkable standard as the finest Indian pieces. Although the pieces from the Turkish Ottoman Empire were not distinguished by the Emperor from those made in northern India, the authors of the National Palace Museum exhibition catalogue suggest that they were neither so numerous at the Chinese court, nor so refined as their Indian counterparts (Catalogue of a Special Exhibition of Hindustan Jade in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1983, p. 73-4). The current jar is typical of the finest jades attributable to Indian origin.

The skill of the lapidaries of this region had long been admired by the Chinese. As early as the Han dynasty it was noted in Chinese texts that the inhabitants of Kashmir/Gandhara region were especially skilled in carving and used such items to decorate their palaces. Among the early Chinese texts there are various references to Indian carved jade and other hardstones. Both the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) Sanfu huangtu and the Jin dynasty (AD 265-420) Shiyi ji, for instance, mention a special yujing (jade crystal) bowl for containing ice, that was presented as a tribute gift from the Gandharan state to the Chinese Emperor Han Wudi (r. 140-87 BC). The major source of nephrite jade for both Chinese and Indian lapidaries was in the region of Khotan. The nephrite deposit is in the Kunlun mountains on the southerly border of Xinjiang, and would thus have been transported over considerable distances to the jade carvers of India and China. Not only the jade but also the lapidaries were sometimes brought from distant lands. Records of the Imperial Household Department indicate that in the Qianlong reign (AD 1762) Moslem jade carvers were sent to work in the ateliers in the Imperial palace, Beijing. This is further proof, if it were needed, of the Emperor's admiration for the fine jades from these regions.

Although the same basic techniques of jade carving were used by the Chinese and the Mughal lapidaries, research suggests that the northern Indian carvers used a bow lathe while seated on the ground, while the Chinese craftsmen used a treadle lathe while seated on a stool. Their choice and use of the raw material was also slightly different. While Chinese carvers incorporated variously coloured inclusions in the jade into their overall design and made use of the outer 'skin' of the jade pebble, the Mughal carvers preferred jade of a single colour. This would have made finding a suitable piece of raw jade for carving an object of any significant size more difficult for the Mughal carvers. The current jar is a fine example of such an even toned piece of jade. Open wares, such as bowls and dishes were often carved very thinly by the Indian lapidaries, to the extent that the Qianlong emperor described them as 'supernaturally made'. However it would not have been practical to have jars of such excessive thinness.

Although gifts of jades from the West had entered China intermittently over a long period, it was during the reign of the Emperor Qianlong that they were especially appreciated. One of the earliest jade tribute-gifts of this reign was the carved jade bowl sent by Bruhan-al-din in 1756. The Qianlong emperor was not only an avid collector, he also enjoyed studying and composing commemorative poems about items in his collection. These poems are recorded in the Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji, and, on the emperor's instructions, a number of them were inscribed onto the pieces themselves. The bowl sent by Bruhan-al-din, which is still in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taiwan, bears such an inscription (Catalogue of a Special Exhibition of Hindustan Jade in the National Palace Museum, op. cit., pp. 126-7, pl. 1). Sixty-four Qianlong poems are recorded for Mughal jades in the imperial collection dating between 1756 and 1794. The National Palace Museum, Taipei has identified nineteen of these on pieces in their collection, and six more in other collections. Now another one of these imperially inscribed Mughal jades has come to light. The exquisite white jade jar in this sale bears a lengthy inscription composed by the emperor and incised into the sides of the jar by palace lapidaries in AD 1783. The text of this inscription, entitled 'Further Praise for a Hindustan Jade Jar' is published in the Qing archives, but the object on which it is inscribed was not previously known to scholars. The inscription may be translated as reading:

'Made ingeniously in Hindustan, the auspicious flower as the foot carries praises; the water-abrasion technique is excellent*, the ring- handles are made with fresh and translucent buds of good fortune. From its fine carving one can see the shimmering of Yunyu**, it is lustrous without and modestly hollow within; its precious pneuma surpasses that of the Liancheng***, its striations concealed to complete its beauty. Making comparisons its brilliance can be likened to the archaic jade goblets; in praising it with poetry one thinks of the ancient panyu dishes****, coincidently I obtained these two treasures*****, again I compose a five-character poem:

Ingeniously made in Hindustan

The quality [of the jade] is high, and the craftsmanship even more superb.

White, unlike a green jadeite bowl,

Its lustre makes a crystal vessel appear dull.

Buds of good omen are formed into ear-handles,

Auspicious flowers are gathered as the foot.

Minute striations are not flaws,

Their existence is concealed, as if they are naught.

The gentleness of its exterior contains virtue,

The hollowness of its interior includes trustworthiness.

Paragraph after paragraph I devote to this treasured vessel,

Inscribing these words I feel only humbled.

Imperially inscribed in the Spring of the Qianlong guimao year [AD 1783].

*The Qianlong Emperor mistakenly believed that unlike Chinese lapidaries, the Indian craftsman used no abrasives, only water to work the jade.

**Yunyu is the name of a legendary elixir of immortality mentioned in the Daoist manual, Yunji Qiqian

***Liancheng is the other name for the ancient jade disc, Heshibi, belonging to the Duke of Zhao in the Warring States period, for which the Duke of Qin offered him fifteen towns.

****The ancient panyu were dishes on which the sages and kings of the past inscribed their meritorious deeds.

*****The two treasures probably refer to the fact that Qianlong acquired two precious vessels at the same time, and had therefore previously composed a poem in their praise. In the Qing Gaozong Yuzhi Shiwen Siji where the current inscription is published, the previous inscription, which also contains a five-character poem and dates to the same year, is entitled, In Praise of a Hindustan Bowl.'

This beautiful jar typifies all the qualities that the Qianlong Emperor so admired in Mughal jades. The shape is elegant and the design incorporates two bands of delicate acanthus leaves around the shoulder and base, while gracefully arched buds provide handles and the foot is formed by an open Indian lotus blossom. The nephrite jade from which the jar is made is of a beautiful, almost luminous, white. So delicate is the colour that it has been likened to clouds. In the text of the inscriptions that he wrote for works of art in his collection, Qianlong often made reference to real or legendary works of art from earlier periods. It is possible that in his reference to a 'crystal vessel' in the inscription on this jar, the Emperor may be paying the jar the rare compliment of indicating that it surpassed the legendary 'jade-crystal' yujing vessel recorded as having been sent from the Gandharan state as a tribute gift to the Han Emperor Wudi.

The decoration on the current jar shares many features with other Hindustan jades. The handles formed from pendant flower buds may be seen on several items of different shapes in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taiwan (Catalogue of a Special Exhibition of Hindustan Jade in the National Palace Museum, pls. 6, 7, 8, 47, 58 and 59) and also on a jar in the Palace Museum, Beijing (The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, Jadeware III, Commercial Press, Hong Kong, 1995, p. 285, no. 7). The precise form of the handles on the current jar is particularly cleverly conceived. Not only do they appear to grow from an elegant leafy stem that rises from the foot of the vessel, as is often the case on such pieces, each is also joined to a leaf that arches over the bud from a little higher on the shoulder. This retains the impression of delicacy while at the same time adding strength and stability to the handle.

The artistic device of forming the foot of the vessel as an open flower is also characteristic of these fine 'Hindustan' jades. Indeed more than half of the Hindustan jades in bowl, jar or dish form in the National Palace Museum have a flower-shaped base or foot. The foot on the current vessel is particularly attractive since it is a little higher than some of the other examples and the open Indian lotus flower is especially well carved. The decoration of acanthus leaves is one of the most popular on these Mughal jades. The two acanthus leaf bands on the current jar are delicately and realistically carved. Their three-dimensional appearance is enhanced by the technique of depicting the edges of some leaves curling inwards, while they are given movement by being carved in at a slightly oblique angle.

The current jar perfectly exemplifies the extraordinary carving seen on the finest of these Mughal jades. The decoration appears three-dimensional although in very low relief. As Qianlong in one of his other poems describes it: 'although the eyes perceive multiple layers, the hand feels the surface to be flat'. The Hindustan lapidaries were also famous for the fact that their carving was so well finished that no trace of the cutting wheel remains. As Qianlong noted the surface is: 'so smooth that it will not disturb the skin when touched'. At the end of the poem composed for this jar the emperor indicates that he feels humbled by its beauty. Looking at the piece one can understand why, and also understand why he appended a seal reading 'pure pleasure'.

Christie's. Chinese Ceramics & Chinese Export Ceramics & Works of Art, London, 12 November 2002

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F24%2F10%2F119589%2F128258452_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F63%2F94%2F119589%2F128246772_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F44%2F15%2F119589%2F126944801_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F08%2F21%2F119589%2F122158571_o.jpg)