Les Arts d'Asie à l'honneur le 23 juin 2020 chez Christie's Paris

© Christie's Image Ltd 2020

Paris – Le 23 juin prochain, Christie's Paris aura le plaisir de présenter sa vente d’Art d’Asie composée de 223 lots, des œuvres d'art d'une provenance et d'une qualité exceptionnelles sélectionnées avec soin par le département Art d’Asie. L’estimation globale est comprise entre 3 millions et 4,500,000 millions d’euros.

Parmi les pièces phares de la vente, mentionnons une rare et importante statue de Marichi en bronze doré d’une taille remarquable datant de l’époque de l’empereur Kangxi (1662-1722). L’œuvre, provenant d’une collection privée française, est restée dans la même famille depuis plusieurs générations (ill. ci-dessus, estimation : €200,000-400,000). Les représentations de Marichi, déesse de la lumière, sont rares, on connait un autre bronze conservé au Musée de Brooklyn, New York datant du XVIIIème siècle et présentant la même iconographie à trois visages dont une tête de sanglier.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Lot 43. Provenant d'une collection privée française. Rare et importante statue de Marichi en bronze doré, Chine, Dynastie Qing, Epoque Kangxi (1662-1722). Hauteur: 43 cm. (17 in.) ; Largeur: 29 cm. (11 ½ in.) ; Profondeur: 19 cm. (7 ½ in.). Estimate EUR 200,000 - EUR 400,000 (USD 226,250 - USD 452,500). Price realised EUR 514,000. © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

Elle est représentée assise en vajrasana sur une double base lotiforme. Ses mains principales sont en abhiseka mudra, ses six autres bras rayonnant autour d’elle tiennent quatre attributs : la lune, le soleil, un sceau et une cloche. Elle est vêtue d’un sari orné de motifs floraux ceinturé à la taille, ses épaules sont recouvertes d'un manteau souple et d’une écharpe flottant gracieusement autour des bras. Elle est parée de bijoux richement ouvragés et incrustés. Son visage principal est serein et flanqué de deux autres visages : l’un à l’expression féroce, l’autre représentant un sanglier. Ces visages sont rehaussés de couronnes ouvragées. Un troisième œil est présent sur chacun des trois fronts. Ses cheveux sont coiffés en un haut chignon surmonté d’une tête de Bouddha ; non scellée.

Provenance: The bronze remained in the same French private family for several generations.

Note: The Buddhist goddess Marichi, whose name means ‘Ray of Light’, is considered to be the Goddess of the Dawn. Ritual prayers to her are recited every morning at dawn. She drives away the night, darkness of ignorance, fear and is associated with light and removing obstacles. She is considered to be the counterpart of the sun god Surya. One of her most prominent iconographic characteristics is a sow or sow-head. Marichi can have different forms with as many as three heads and eight arms holding various attributes. The sow however is a constant iconographic characteristic whether by riding a chariot drawn by seven sow's, seated on a pig or represented with a sow’s head like the fine gilt-bronze example offered through our rooms.

In Tibet, Marichi is considered to be a form of the goddess Vajravarahi. It is not unlikely that Vajravarahi and thus as well Marichi is conceived by Buddhist teachers as an answer to the Hindu Varahi, one of the mother goddesses. Varahi enjoyed an independent cult and was regarded as a powerful deity in eastern India. It was indeed in this region under the Pala rulers during the eleventh to twelfth century that the first Buddhist Marichi examples can be found. Such an early gilt-bronze example is published by Ulrich von Schroeder in his monumental work ‘Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, vol. one, India & Nepal, Visual Dharma Publications Ltd., Hong Kong 2001, pl. 93 C. The Marichi cult found her way to Tibet, although again rarely to be encountered. A parcel gilt-bronze figure of her riding a chariot drawn by pigs and dated by the author to the thirteenth century is presently in the Summer Palace at Chengde and illustrated in Buddhist Art from Rehol: Tibetan Buddhist images and ritual objects from the Qing dynasty Summer Palace at Chengde, Chang Foundation, Taipei 1999, pl. 23.

She became part and parcel of an extended Vajrayana Buddhist repertoire. Tibetan Buddhist teachers introduced this specific Buddhist school in China during the Yuan dynasty. The first Marichi examples in China seem to have appeared only during the early Ming dynasty. A fine gilt-bronze Yongle (r. 1402-1424) example seated on a caparisoned sow is published by Ulrich von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, vol. two, Tibet & China, Visual Dharma Publishing Ltd., Hong Kong 2001, pl. 357 B.

Her appearance in Chinese, as in Tibetan religious art is extremely rare and just a few examples are published. In due time she became adopted as well by the more popular form of Buddhism in China. Here she is believed to be the mother of the Northern Star and referred to as ‘Dipper Mother’ (Doumu Yuanjun), a constellation in Sagittarius. Furthermore she even appeared in Daoism where she is often considered as the Queen of Heaven (Tian Hou).

As said Marichi can have different forms. The present superb gilt-bronze example shows three faces, including a central benign one flanked by a wrathful face and a sow’s head and she has eight arms. In general the goddess can hold a variety of attributes including moon, sun, needle, seal, bell, a thread, vajra, lasso, bow and arrow. Most prominent attributes shown here are the sun and moon emblems.

Another Chinese gilt-bronze Marichi example dated to the eighteenth century, though holding different attributes and of much smaller size (h. 26 cm) is published by Barbara Lipton and Nima Dorjee Ragnubs in Treasures of Tibetan Art: Collections of the Jacques Marchais Museum of Tibetan Art, Oxford University Press, New York 1996, pl. 52. A much large Chinese example (h. 91.4 cm), showing as well the sun and moon emblems, is located in the Brooklyn Museum, New York, accession number 10.221 (fig.1).

.jpg)

Gilt Figure of Marichi, 18th century. Bronze with traces of gilding, 36 × 37 × 22 in. (91.4 × 94 × 55.9 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Robert B. Woodward and Carll H. de Silver, 10.221.

Most likely the presented important Marichi gilt-bronze figure was created in one of the imperial ateliers during the Kangxi reign. He was an ardent follower of Tibetan Buddhism and many important bronzes were made during his reign. Especially if one compares the present example with the well-known Amitayus bronzes the figure demonstrates similar stylistic characteristics. See an Important bronze of Amitayus from Kangxi period sold in Christie's Paris, lot 412 A, 7 June 2011.

La délicatesse de la céramique chinoise sera mise en lumière à travers des œuvres de différentes époques. Citons un rare bol d’un raffinement exquis en grès Yaozhou datant de la fin de la dynastie Song - début de la dynastie Jin provenant d’une collection privée japonaise, estimé €70,000-90,000, ill. à gauche. On connait peu d’exemples aux formes et aux décorations similaires si finement réalisées : un se trouve dans les collections du Musée du Palais, à Pékin, un autre est conservé au Musée national de Tokyo auquel a été attribué le statut national particulier d’« objet d’art important » soulignant d’autant plus la rareté de ce type de bol.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Lot 109. Rare et important bol en grès Yaozhou, Chine, Dynastie Song du Nord - Dynastie Jin (960-1234). Diamètre: 23,3 cm. (9 ⅛ in.), boîte en bois japonaise. Estimate EUR 70,000 - EUR 90,000 (USD 79,163 - USD 101,781). © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

Cet élégant bol est orné à l'intérieur comme à l'extérieur d'un décor de rinceaux végétaux incisés. Il est recouvert d'une belle glaçure vert olive s'arrêtant juste au dessus de son pied court.

Provenance: Private Japanese Collection, acquired in the 1980s.

For Elegant Gatherings -A Rare and Important Yaozhou Bowl

Rosemary Scott, Senior International Academic Consultant

Bowls of this distinctive form are believed to have been used as warming bowls for small wine ewers at elegant gatherings in the Song dynasty. Certain types of wine were served warm and so the ewer holding the wine stood in a bowl of this type, containing hot water, which would help to retain the warmth of the wine. Such warming bowls and ewers are occasionally seen among the celadon-glazed Yue wares from Zhejiang, as in the case of the Yue bowl and ewer, now in the Capital Museum, Beijing, which were excavated in 1981 near Beijing from a Five Dynasties tomb dated to AD 995. Song dynasty ceramic sets of wine ewer and warming bowl are more common amongst qingbai glazed porcelains from the Jingdezhen kilns of Jiangxi province, but small numbers of Yaozhou examples are known, including that in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in The Complete Treasures of the Palace Museum, 32, Porcelain of the Song Dynasty (I), Hong Kong, 1996, pp. 114-5, no. 102). The Palace Museum bowl bears similar decoration to the current bowl, but is a little less finely-made, while its glaze lacks the brilliance and clarity of the glaze on the current vessel. Similar bowls are known in sizes ranging from 21.5 cm. diameter, to 23.5 cm. diameter. The Palace Museum bowl is of the smaller type, while the current bowl has a diameter of 23.3 cm.

Bowls and ewers for the serving and retaining the warmth of wine are depicted in a number of extant paintings of elite gatherings, such as The Night Revels of Han Xizai by Gu Hongzhong (AD 937-975), a 12th century copy of which is in the Palace Museum, Beijing; Literary Gathering by the Northern Song Emperor Huizong ( r. 1100-1126), which is in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei; and Eighteen Scholars of the Tang, which has also traditionally been attributed to Emperor Huizong, and is also in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei. The fact that a ewer was intended to stand in the bowl possibly explains why there is a neat unglazed ring on the interior of the current, and similar, Yaozhou bowls. When the unglazed foot rim of the ewer was placed upon it, the unglazed ring inside the bowl would have provided a small amount of friction, which would have prevented the ewer from sliding about inside the bowl when the vessels were carried together to and from the table.

The carved decoration on this bowl and the small number of related bowls is both unusual and distinctive. The interior walls are decorated with a carved and combed design of lotus flowers and leaves on water, while the exterior has a wide band of so-called ‘cash pattern’, below which is a somewhat narrower vegetal scroll band. This decoration is all carved using the characteristic Yaozhou technique, which involved the decorator holding the carving implement at an angle, so that one side of the cut went deeper into the clay then the other. When combined with the ideal Yaozhou glaze, such as that seen on the current bowl, the transparent olive-green glaze pooled in the deeper incision, appearing darker and producing a particularly effective dichromatic effect, which enhanced the impact of the design.

The current bowl is a particularly fine example of the brilliant olive-green glaze for which these kilns are famous. The potters at Yaozhou were believed to have used a specific type of local rock as a significant ingredient in the glazes. Research has shown that this rock, called fuping glaze stone, could have been pulverized and simply mixed with small amounts of clay, silica and a phosphatic flux, such as wood ash, in order to make a good celadon glaze. Like the glaze on the earlier Yue celadon-glazed wares, the Yaozhou glaze was a so-called ‘lime glaze’, in contrast with the later Longquan celadon glazes which were ‘lime-alkali glazes’. The best Yaozhou glazes, like that on the current bowl, are transparent, bright, glossy, and olive green in colour. They contain relatively few large gas bubbles to obscure the design, but do contain very fine bubbles which scatter the light and add brilliance to the glaze.

Fine Yaozhou celadon wares were highly prized in the Northern Song and Jin dynasties, and were presented as tribute to the Northern Song court. Both the Song Shi (Official History of the Song) and the Yuanfeng jiu yu zhi (Gazetteer for the Empire’s Nine Regions in the Yuanfeng reign [1078-1085]), compiled by Wang Cun (1023-1102), mention such tribute gifts. Indeed, fifty sets of tribute ceramics from the Yaozhou kilns are mentioned as being sent to the court over the period from AD 1078 to 1106. The appreciation of fine celadon-glazed wares at the Chinese court had been established in the Five Dynasties and early Song dynasty when celadon-glazed Yue wares were sent as tribute from Zhejiang province. As the popularity of white-glazed Ding wares began to wane at court in late 11th century, Yaozhou celadons became increasingly popular.

A small number of Yaozhou celadon bowls of similar shape and decoration to the current bowl are known. A kiln waster of such a bowl has been excavated from amongst the Jin dynasty remains at the Yaozhou kiln site (see Shaanxi Tongchuan Yaozhouyao, Beijing, 1965, pl. xxi:3). Complete bowls of this type are also in the Barlow Collection (illustrated by M. Medley in Yüan Porcelain and Stoneware, London, 1974, pl. 79A), and in the Asia Society New York (illustrated by Y. Mino and K. Tsiang in Ice and Green Clouds: Traditions of Chinese Celadon, Indianapolis, 1987, pp. 152-3, no. 58). The latter bowl bears an inscription in ink on the interior, which is generally accepted to be of the period, and which provides a date equivalent to AD 1162. A further similar bowl, but with an additional decorative band around the interior rim, is in the collection of the Henan Provincial Museum (illustrated in Museums of China, vol. 7, Henansheng bowuguan, Tokyo, 1983, pl. 131).

The considerable importance attached to bowls of this kind in Japan can be inferred from the fact that two Yaozhou bowls of similar shape and decoration to the current bowl have been accorded the national status of ‘Important Art Object’. One of these was previously with the famous dealer Junkichi Mayuyama, and was published in Mayuyama, Seventy Years, Volume One, Tokyo, 1976, p. 120, no. 345. This bowl was sold by Sotheby’s New York in September 2018. The other similar bowl given the status ‘Important Art Object’ is in the collection of the Tokyo National Museum and was included in the exhibition Masterpieces of Yaozhou Ware, held at the Museum of Oriental Ceramics, Osaka, in 1997, and illustrated as catalogue no. 96.

Mentionnons également un rare bol "floral" Falangcai à fond rubis délicatement orné d’une série de fleurs datant de l’époque Yongzheng (€120,000-150,000). Deux bols réalisés sur ce modèle se trouvent au Musée national du Palais, à Taipei, ainsi qu’un autre au British Museum de Londres.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Lot 150. Provenant d'une collection privée. Rare bol Falangcai à fond rubis, Chine, Dynastie Qing, marque à quatre caractères dans un double carré en bleu sous couverte et époque Yongzheng (1723-1735). Diamètre: 9,2 cm. (3.5/8 in.). Estimate EUR 120,000 - EUR 150,000 (USD 135,708 - USD 169,635). Price realised EUR 382,000. © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

Reposant sur un petit pied, il est délicatement orné d'une série de fleurs épanouies comprenant la pivoine, l'hibiscus, le lys, le chrysanthème, le camélia et l'aster, le tout sur un fond émaillé couleur rubis. La base porte une marque Yongzheng Yuzhi à quatre caractères dans un double carrré.

Provenance: Sotheby's Hong Kong, 8 October 2013, lot 3258.

Note: The decoration on the present lot was based on an earlier Kangxi type which had a different form and a coral-red ground. A pair of these Kangxi examples from the T.Y. Chao collection were sold at Sotheby's Hong Kong, 19 May 1987, lot 303, including one which is illustrated in Geng Baochang, Ming Qing ciqi jianding, Hong Kong, 1993, pl. 379.

The present bowl belongs to a small group of vessels exclusively made for the Yongzheng emperor which bear the Yongzheng yuzhi marks. From the Yongzheng period onwards this design begins to be reserved on a ruby ground rather than a coral-red one. One example sold at Sotheby's Hong Kong, 29 November 1977, lot 163, is illustrated in Sotheby's Hong Kong, Twenty Years: 1973-1993, Hong Kong, 1993, pl. 221, together with a Jiaqing version of the same pattern, pl. 222. Two bowls of this design are in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, and are illustrated in Porcelain of the National Palace Museum: Fine Enamelled Ware of the Ch'ing Dynasty: Yung-cheng Period, vol. II, Hong Kong, 1967, pls 34-35. Another example in the British Museum in London is illustrated by Hugh Moss, By Imperial Command, Hong Kong, 1976, pl. 5. Also see one in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, published by Rose Kerr, Chinese Art and Design, London, 1992, pl. 92 (right); one from the T.Y. Chao collection which was sold at Sotheby's Hong Kong, 18 November 1986, lot 130, and again on 5 November 1996, lot 87. Another pair of bowls was sold at Sotheby's Hong Kong, 9 October 2007, lot 1508.

Provenant de l’ancienne collection privée de Monsieur Robert Rousset (1901-1982), l'un des plus éminents marchand français et pionniers de l'art chinois à Paris, Christie’s proposera un rare miroir en émaux cloisonnés, de l’époque Kangxi (estimé €18,000 – 22,000), ainsi qu’une superbe boîte, en bronze doré et émaux cloisonnés datant du XVème siècle, délicatement ornée sur le couvercle de grandes fleurs d'automne d'hibiscus jaunes, un motif d’une grande rareté dans les arts décoratifs de l’époque et que l’on retrouve aujourd’hui sur des pièces muséales. Elle est estimée €50,000-70,000.

Lot 22. Provenant de la collection de M. Robert Rousset. (1901-1982). Rare et importante boîte couverte en émaux cloisonnés, Chine, Dynastie Ming, XVe siècle. Diamètre: 16,7 cm. (6 ½ in.) ; hauteur: 5 cm. (2 in.). Estimate EUR 50,000 - EUR 70,000 (USD 56,545 - USD 79,163). Price realised EUR 586,000. © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

De forme ciculaire, elle est délicatement ornée sur le couvercle de grandes fleurs d'automne d'hibiscus jaunes parmi leur feuillage effilé vert et bleu turquoise sur fond bleu nuit. Le revers est orné de pampres émaillées noir parmi les feuilles de vigne d'un vert dense souligné de jaune et de rouge sur fond bleu turquoise.

Provenance: Previously in the private collection of Robert Rousset (1901-1982), Compagnie de la Chine et des Indes, Paris, thence by descent in the family.

A Beautiful and Rare 15th Century Cloisonné Box

Rosemary Scott, Senior International Academic Consultant, Asian Art

This exquisite little cloisonné box is decorated on the base with clusters of deep purple grapes and on the lid with a very rare design of yellow autumn hibiscus (Abelmoschus manihot, 黃秋葵 huang qiukui). The cloisonné artist has been at pains to use fine gilded lines to emphasize the delicacy of the veining on the flower petals, and has used a deep purplish-red with great restraint to indicate the characteristic dark centre of the bloom.

Although seldom applied to the decorative arts, yellow autumn hibiscus was a popular subject for painters from the Song dynasty onwards and can be seen in a number of extant early works such as Hibiscus and Rock by Li Di 李迪 (ca. AD 1100 – after AD 1197), now in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei. With its delicate blooms and subtle fragrance, autumn hibiscus was seen as a symbol of beauty and virtue, while its association with humility also endeared it to retired scholar officials. Among the earliest surviving depictions of autumn hibiscus on the decorative arts is a rare Southern Song (1127-1279) or Yuan dynasty (1271-1368) square painted lacquer tray in the collection of the Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, which has a spray of these flowers painted in colours and gold in the centre (see Terese Tse Bartholomew, The Hundred Flowers – Botanical Motifs in Chinese Art, San Francisco, 1985, no. 41). Autumn hibiscus also appear on a famous circular carved lacquer ‘birds’ dish in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. This carved vermilion lacquer dish is dated to the Yuan or early Ming dynasty, and came from the Florence and Herbert Irving Collection. It is illustrated by J.C.Y. Watt and B. Brennan Form in East Asian Lacquer – The Florence and Herbert Irving Collection, New York, 1991, pp. 68-9, no. 19. The volume misidentifies the flowers as ‘hollyhock’, but it is surely autumn hibiscus which provide such effective visual counterpoint to the birds in the complex decorative scheme on the Irving dish.

Yellow autumn hibiscus appears on several extant woven decorative 緙絲 kesi panels dating to the Ming dynasty. The Liaoning Provincial Museum, Shenyang, and the National Palace Museum, Taipei each has in its collection a kesi tapestry depicting yellow autumn hibiscus with yellow chrysanthemums and blue asters beside rocks, on one of which a bird is perched. The scene is known as 三秋 san qiu (Three Autumns), and is believed to have been inspired by a work from the Song dynasty artist Cui Bo (崔白active 1068-77).

Perhaps most significant in the context of the current cloisonné box, autumn hibiscus is one the flowers that provides the rarest of all the designs on blue and white porcelain ‘palace’ bowls made for the Chenghua Emperor. Porcelain bowls of this design have been excavated from the late Chenghua stratum at the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen (see The Emperor’s broken china – Reconstructing Chenghua porcelain, London, 1995, pp. 60 and 64, no. 69). A complete bowl of this type is in the collection of Sir Percival David (illustrated by Rosemary Scott and Stacey Pierson in Flawless Porcelains: Imperial Ceramics from the Reign of the Chenghua Emperor, London, 1995, p. 22, no. 1). The appearance of autumn hibiscus on imperial Chenghua porcelain is particularly interesting when one considers that clusters of grapes were also a favoured motif on imperial Chenghua porcelain. Indeed, the two motifs on Chenghua doucai porcelains which have been the most esteemed since the 15th century are ‘chickens’ and grapes. The doucai grape motif was especially prized for the rich enamel colours employed on the grapes themselves, which can be seen on small dishes and on small cups with low foot and small stem cups (see A Legacy of Chenghua – Imperial Porcelain of the Chenghua Reign Excavated from Zhushan, Jingdezhen, Hong Kong, 1998, pp. 288-9, no. C100 and pp. 296-7, no. C104). Scientists have suggested a close relationship between the enamels used on cloisonné enamels and those used as overglaze enamels on porcelain, and the richness of the deep purple used for the grapes on the current cloisonné enamel box is particularly striking.

While still relatively rare on cloisonné enamels of the 15th century, grapes do appear on a small number of vessels – especially tripod censers. A small cloisonné enamel li censer from the collection of Pierre Uldry is decorated with clusters of grapes descending down each of its pouched legs (see Helmut Brinker and Albert Lutz, Chinese Cloisonné – The Pierre Uldry Collection, New York, 1989, no. 35). This tripod, which is dated to the second half of the 15th century, provides an interesting comparison to the base of the current box, as it shares both the enamel colours and the shape of the cloisons used in the depiction of specific elements. It is particularly significant that both vessels share the sophisticated use of three enamel colours – dark green, yellow and red – applied to a single leaf. While the use of two colours is seen quite regularly, the use of three colours – with its concomitant firing difficulties – is much rarer. This impressive shading of three colours on a single leaf is also seen on some of the hibiscus leaves on the lid of the current box.

The choice of grapes as a decorative motif is interesting since, unlike autumn hibiscus, grapes do not appear to have been indigenous to China, but are among the plants that are recorded as having been introduced to China from Central Asia by Zhang Qian, a returning envoy of Emperor Wudi in 128 BC. However, by the early 15th century many different varieties of grape were grown in China. Indeed, records show that both green and black grapes were grown by the beginning of the 6th century AD, and Song dynasty texts mention a seedless variety. An extensive illustrated entry on grapes (Vitis vinifera, Chinese 葡萄 putao) is included in 卷 juan 23 of the 重修政和經史證類備用本草 Chongxiu Zhenghe Jingshi Zhenglei Beiyong Bencao (Classified and Consolidated Armamentarium Pharmacopoeia of the Zhenghe Reign [AD 1111-1117]). Grapes rarely appeared as decoration on Chinese art objects of the early period, with the exception of those depicted in relief on pilgrim flasks of the period Six Dynasties-Sui Dynasty (AD 6th-7th century) – see Masahiko Sato and Gakuji Hasebe (eds.), Sekai Toji Zenshu 11 Sui Tang, Tokyo, 1976, p. 38, no. 25 - which were influenced by the arts of Central and Western Asia. Grapes became a more popular motif in the Tang dynasty, when, again following inspiration from the west, they regularly appeared, for example, as part of the ubiquitous 'lion and grape' motif on bronze mirrors. As, far as grapes painted on Chinese ceramics is concerned, they appeared occasionally as a minor part of the decoration with other plants, on 14th century Yuan dynasty blue and white vessels, as on the shoulder of the Yuan jar illustrated by 朱裕平Zhu Yuping, 元代青花瓷Yuandai qinghua ci, Shanghai, 2000, p. 156, no. 48, but it was in the early 15th century that grapes became a really popular motif on imperial porcelains decorated in underglaze cobalt blue and begin to appear on cloisonné enamels. By the 16th century grapes were a popular choice for cloisonné enamel decoration, but it may be argued that the 15th century depictions are the more delicate and sophisticated in their decorative schemes and use of colour.

The current box is an exquisite example of the cloisonné enamel craftman’s art, and it seems probable that it dates to the reign of the Chenghua Emperor.

Les collectionneurs auront également l'occasion d'acquérir un important vase Zun archaïque finement moulé de la fin de la dynastie Shang, début de la dynastie Zhou (€100,000-150,000) provenant d'une collection privée européenne.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Lot 103. Provenant d'une collection privée européenne. Vase rituel en bronze, Zun, Chine, fin de la Dynastie Shang - début de la Dynastie Zhou de l'Ouest (XIIe-Xe siècle av. JC). Hauteur: 26,3 cm. (10 ⅜ in.). Estimate EUR 100,000 - EUR 150,000 (USD 113,090 - USD 169,635). Price realised EUR 200,000. © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

La partie centrale du vase de forme renflée est très délicatement moulée de masques de taotie sur un riche fond de leiwen, entrecoupés d'arêtes verticales mouvementées en relief. Le large col évasé est ceint d'une bande de dragons stylisés sous de larges palmes toujours divisées par les mêmes arêtes en relief se continuant jusqu'au bord. La patine de couleur vert foncé tirant vers le noir est ponctuée d'incrustations par endroits.

Provenance: Acquired at Raf Huser Antiquitäten, Switzerland, 15 December 1997.

Note: The present zun, with its prominent vertical flanges and intricate decoration, is representative of the type made during the late Shang period to Early Western Zhou period. Bronze casting came fully into its own in China during the Shang dynasty with the production of sacral vessels intended for use in funerary ceremonies. These vessels include ones for food and wine, as well as ones for water. The present wine vessel, zun, simultaneously displays features from the Shang period, such as the dominant vertical flanges and the taotie masks with bulging eyes, as well as the bird-shaped decorative motif often found on Western Zhou bronzes. A rare feature of the present vessel is the extension of the flanges over the mouth rim. This feature usually appears on vessel types of the highest status, such as the fangzun from the Fujita Museum, sold at Christie’s New York, 15 March 2017, lot 523; and the fine pair of Late Shang dynasty gu, the tie zhu gu, sold at Christie’s New York, 22 March 2019, lot 1504.

A zun of similar size, cast with cicada-like forms and vertical flanges, dated to the Western Zhou dynasty from the Art Institute Chicago is illustrated by Charles Fabens Kelley and Ch’en Meng-Chia in Chinese Bronzes from the Buckingham Collection, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1946, pp. 48-49, plate 23. A vessel of similar style, from the Shanghai Museum is illustrated by Chen Peifen in Ancient Chinese Bronzes in the Shanghai Museum, London, 1995, p. 41, where it is dated to the Late Shang period. Another Early Western Zhou example of a similar shaped zun from the Cleveland Museum of Art is illustrated by Jessica Rawson in Western Zhou Ritual Bronzes from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1990, Vol. IIB, p. 579, Fig. 87.9. A comparable zun, similar in form but without flanges on the upper part, also from the Sackler Collections, is illustrated by R. Bagley in Shang Ritual Bronzes in the Arthur M. Sackler Collections, Washington DC and Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1987, pp. 310-311.

A zun very similar to the present one in style, dated to the Late Shang-Early Western Zhou Dynasty was sold at Christie’s London, 15 May 2018, lot 40.

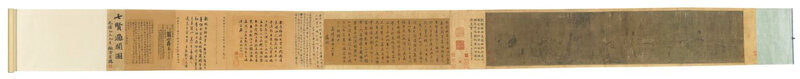

D’importantes peintures chinoises de différentes époques seront aussi placées sous le feu des enchères, notamment un rouleau important portant la signature de Li Gonglin (1041-1106), Sept sages traversant le passage (estimé €35,000-45,000) et dont les colophons mentionnent des personnalités célèbres.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Lot 80. Signature de Li Gonglin (1041-1106), Sept Sages Traversant Le Passage. Monté en rouleau, encre sur soie. Dimensions: 28,6 x 182,9 cm. (11 ¼ x 72 in.). Estimate EUR 35,000 - EUR 45,000 (USD 39,581 - USD 50,890). Price realised EUR 62,500. © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

Signature et deux cachets partiellement effacés de l'artiste.

Colophon par Qian Yong (1759-1844), daté de l'année wuchen (1808) de l'époque Jiaqing, avec un cachet.

Colophon avec la signature de Wen Zhengming, daté de l'année gengshen de l'époque jiaqing period (1560), avec deux cachets.

Premier colophon par Qian Tianshu (1778-1841), daté de l'année renshen (1812), avec deux cachets.

Deuxième colophon par Qian Tianshu (1778-1841), daté de l'année yimo, 15ème année de l'époque Daoguang (1835), avec un cachet.

Colophon par Sun Yuanxiang (1760-1829), daté de l'année dingchou de l'époque Jiaqing (1817), avec deux cachets.

Colophon par Jiang Yinpei (1768-1838), daté de l'année gengyin de l'époque Daoguang (1830), avec un cachet.

Colophon de Xi Peilan (1760-1829), daté de l'année jimao de l'époque Jiaqing (1819), avec un cachet.

Colophon de Wei Hengkui (m. 1853), daté de l'année renyin de l'époque Daoguang (1842), avec un cachet.

Colophon de Sun Yuanchao (actif milieu du XIXe siècle), datée de l'année jiazi de l'époque Tongzhi period (1864), avec deux cachets.

Colophon de Tao Junxuan (1849-1915), daté du neuvième mois de l'année gengyin de l'époque Daoguang (1843), avec un cachet.

28 cachets de collectionneurs.

Provenance: Collection of Dr John Lamont (d.2012), likely acquired in the early 20th cenury by Dr Lamont's grandfather, Robert P. Lamont (1847-1948), Commerce Secretary to US President Hoover (1929-1932).

Literature: "Seven Worthies Crossing the Pass: A Lost Painting by Li Gonglin", Barnhart, Richard, in Orientations 45.2, March 2014, pp. 100-109

The Legacy of Li Gonglin (1041-1106)

Li Gonglin was one of the most significant painters in Chinese history. He was part of an elite circle of Northern Song painters, poets and calligraphers, including Su Shi (1037-1101), Mi Fu (1051-1107) and Huang Tingjian (1045-1105). Li’s characteristic plain line drawing, or baimiao, was a consummate mastery of descriptive linear brushwork. Controlled, refined, and uniquely expressive, Li’s technical and stylistic legacy is preserved in only a handful of works. While extant paintings definitively from Li’s own hand are excruciatingly rare, Li’s artistic legacy resonated through the centuries following his death in 1106. The following two lots represent distinct but complimentary facets of Li’s artistic legacy.

The first of these two paintings Seven Worthies Crossing the Pass, depicts eminent figures of antiquity riding across a pass in the depths of winter: four on horseback, two on mules, and one astride an ox. While we cannot be certain of the identity of the seven riders, their cultural association with ideas of lofty virtue, implications of transcendence in their journey, and their popularity as a subject for scholar painters is unequivocally attested by written records. Moreover, the connection of this theme to Li Gonglin’s oeuvre is attested in colophon by Yuan connoisseur Ke Jiusi (1312-1365), on a work attributed to Li Tang (c.1050-1130) in the National Palace Museum in Taipei, which states that Li painted the subject often.

The present painting includes several colophons by Qing scholar officials and collectors from the Jiangnan region, reproduced in full in the Chinese description of the painting in the present catalogue. Some of these Qing scholars attribute the work to an unknown Song dynasty follower of Li, while other unequivocally regard it as a genuine masterpiece by Li’s own hand. A more recent appraisal of the present painting was published by Richard Barnhart in Orientations in 2014, under the subtitle “a lost painting by Li Gonglin”.

The painting is a deftly executed, strikingly animated composition. As Barnhart notes, the interaction between figures in the present work echoes the interplay of gestures, glances and individualised expressions seen in Li Gonglin’s Classic of Filial Piety, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. However, in Barnhart’s appraisal, the closest parallel with Li’s accepted works is with Li’s Five Horses, a work recently rediscovered and now in the Tokyo National Museum (illustrated here, p 87). In Barnhart estimation: “Comparison of the head of the fifth groom in Li’s Five Horses with the second rider in the present scroll reveals further similarities of a kind that suggest a singular technique of drawing and shaping of a head.” (Barnhart, p.103).

The second of the following two lots illustrates a different aspect of Li’s legacy, as a full colour copy of Li’s Five Horses. The present version of Five Horses is clearly later in date than Seven Worthies Crossing the Pass. Moreover, it is an unequivocal homage to Li’s original masterpiece of eleventh century equestrian painting. However, there are incongruous, almost playful additions in the form of its frontispiece, signature and colophons.

The frontispiece that dominates the opening of scroll prominently displays an animated calligraphic title, with a signature of the tenth century Song calligrapher Gao Yi. This anachronism is further underscored by the addition of the signature of tenth century painter Zhao Yuanzhang, small and unassuming, at the very end of the painting. Very little is known of Zhao, and none of his works survive into the present. The signature and the frontispiece provide the viewer with anachronisms that test their knowledge of Song painting, as the putative inscriber and artist both predate Li Gonglin’s Five Horses by around a century. The various colophons explore the calligraphic styles of Yuan and Ming masters, and even the brushwork of the Qianlong emperor. Furthermore, the seals on the painting and frontispiece include impressions reproducing the seals of Song Emperor Huizong, as a further illustration that the artist behind the present work sought to reproduce a broad range of historical models.

Suffused with impactful colour, dextrous brush work, and experimental vigour, this work clearly comes from a masterful yet playful hand. It was quite possibly an exploratory work by a pre-eminent artist of the modern era, experimenting with the Li’s classical style, studying historic calligraphic and seal carving techniques, and perhaps even testing his viewers art historical knowledge through the addition of anachronistic signatures and inscriptions.

Mais également des œuvres plus récentes, telles que les superbes Pivoines réalisées par Qi Baishi (1864-1957) signée du cachet de l’artiste et acquise directement auprès de lui en 1956 par le photographe allemand Hilmar Pabel (€30,000-50,000).

.jpg)

Lot 93. Provenant d'une collection privée allemande. Qi Baishi (1863-1957), Pivoines, Inscrit, signé, et avec un cachet de l’artiste. Rouleau, monté et encadré, encre et couleur sur papier. Dimensions: 51 x 31,5 cm. (20 ⅛ x 12 ⅜ in.). Estimate EUR 30,000 - EUR 50,000 (USD 33,927 - USD 56,545). Price realised EUR 778,000. © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

Provenance: Acquired directly from the artist in 1956 by German photographer Hilmar Pabel (1910-2000), subsequently gifted to the family of the present owner by the Pabel family.

Literature: Hilmar Pabel, Antliz des Ostens, Hamburg, 1960, pp.51-52.

Note: Eminent German photographer Hilmar Pabel acquired the present painting directly from Qi Baishi in China in 1956. Pabel published a collection of his photographs from Asia in 1960 as Antliz des Ostens, including a record of his meeting with Qi (fig. 1). In the accompanying text, Pabel reflects on how privileged he felt to have the opportunity to take a portrait of Qi in his studio. He also states that Qi had painted the present work the morning of their meeting, and gave it to him as a gift which he later displayed in his home in Germany, giving him great pleasure. The painting is representative of Qi’s final oeuvre. The brushwork is empathic and animated, supported by diffuse washes of colour. It is a compelling demonstration of Qi’s continued artistic abilities into the last years of his life.

Please note: an original copy of Hilmar Pabel, Antliz des Ostens is included as part of this lot.

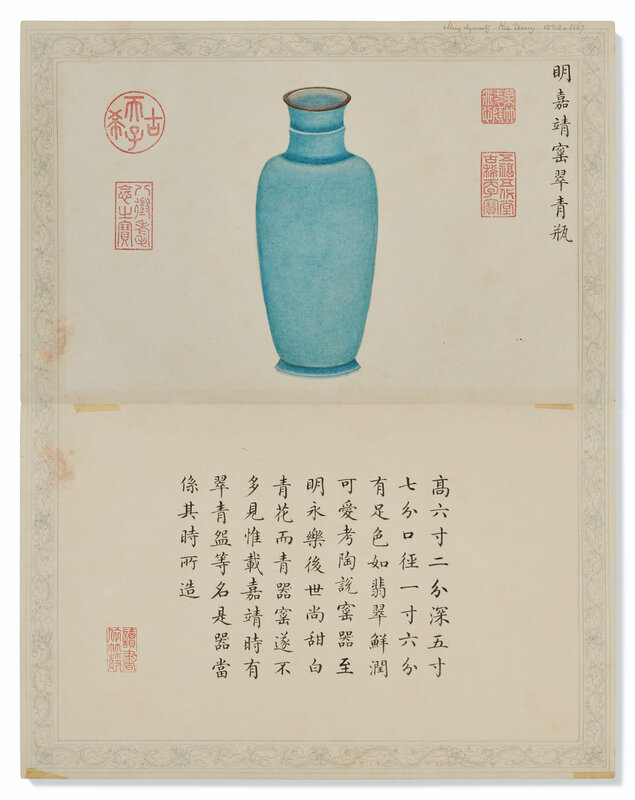

Enfin, les collectionneurs pourront s’emparer de deux doubles pages d’album, extrêmement rares, dédiées à la collection personnelle de porcelaine impériale de l'empereur Qianlong, estimées €50,000-70,000. Ces deux doubles pages ressemblent de façon frappante à l'album impérial de dix feuilles intitulées "Les céramiques raffinées de l'Antiquité" (Jing Tao Yun Gu), réalisées à la demande de l'empereur Qianlong dans les années 1790-1795 pour illustrer les pièces préférées de sa collection avant de les ranger dans des boîtes précieuses. L’album se trouve aujourd’hui au Musée national du Palais, Taipei.

Lot 82. Deux rares et importantes doubles pages d'album de porcelaine Imperiale, Chine, Dynastie Qing, Epoque Qianlong (1736-1795). Dimensions de la double page: 56,5 x 44 cm. (22 ¼ x 17 ¼ in.). Estimate EUR 50,000 - EUR 70,000 (USD 56,545 - USD 79,163). Price realised EUR 200,000. © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

La partie supérieure des deux doubles pages représente deux peintures: un vase en porcelaine émaillée turquoise daté Jiajing (1522-1566) et une coupe en porcelaine rouge de cuivre datée Xuande (1426-1435), tous les deux accompagnés de leur nom et date écrits au pinceau au coin supérieur droit. Les pages inférieures présentent une description détaillée de la pièce représentée au-dessus comprenant la dimension, la couleur, le type de porcelaine ainsi qu'une appréciation subjective de l'empereur. Chaque double page contient cinq cachets impériaux de l'empereur Qianlong ; la bordure est à décor de rinceaux feuillagés dessinés à l'encre grise.

Les doubles pages ont été séparées à la pliure en deux parties pour être encadrées par l'ancien propriétaire, une des pages est restée collée à sa couverture en bois.

Provenance: Previously from a distinguished English family.

Note: These current album pages depicting the personal porcelain collection of the Emperor Qianlong are extremely rare. According to the Imperial Workshop Archives (Huoji dang), the Qianlong emperor assembled a series of ‘boxes of many treasures’ (duobaoge) to classify and rearrange his favourite pieces among his personal collection of ceramics and archaic bronzes between 1755 and 1790. To accompany these boxes, he commissioned specific painting albums to record every single piece which were then placed carefully into each treasures box.

Our two album pages were separated into two parts to be framed as paintings by the former English collector and the lower half of the double page containing the inscriptions were hidden behind the frames. All together, they form two double pages strikingly similar to the imperial album of ten leaves entitled "the Refined Ceramics of Collected Antiquity" (Jing Tao Yun Gu), ordered by the Emperor Qianlong around the fifty-fifth year of his reign (1790) for one of his duobaoge containing a selection of Song and Ming ceramics, today conserved in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, illustrated in Yu Pei-Chin, “De Jia Qu: Obtaining refined enjoyment: The Qianlong emperor’s taste in ceramics”, 2012, P.27. The extreme similarities in the treatment of the floral border, the choice and even the placement of the imperial seals suggest that the current two album pages were likely produced around the same time as Jing Tao Yun Gu, by the end of the emperor Qianlong’s reign, around 1790.

Just like our albums leaves, each page in the Jing Tao Yun Gu depicts a coloured drawing of one individual porcelain piece painted with high realism in the upper page and a physical description of the object including the name, the dating, the colour, the dimensions, the type of kiln and a personal comment on the lower half. Highly realism in the brushwork reflects the influences of the Western court painters but also the emperor’s wish to keep an accurate visual record of each object, with all its noteworthy features. For instance, on the copper red Xuande dish of one of our album leaves, the meticulous court painter objectively rendered the frits and the wear around the rims. This type of realistic illustrations reminds us of the beautiful handscroll “Pictures of Ancient Playthings” (Guwan tu) ordered and painted by his father, under the Yongzheng emperor’s reign, today in the collection of the Victoria and Albert museum (Museum number: E.59-1911). However, compared to the form of the pictorial inventory in Gu Wan Tu, the Qianlong’s emperor’s albums clearly give more importance to the individual identity of each object, just like a museum record or an illustrated catalogue. The presence of numerous personal seals of the emperor also shows that these albums and objects were contemplated, appreciated and deeply treasured by the Emperor himself.

There are eight such albums preserved in collection of the National Palace Museum in Taipei. According to Yu Pei-chin, there were at least fourteen similar albums and more than twenty treasures boxes containing ceramics and bronzes assembled during the Qianlong reign.

The records of these albums constitute inestimable sources of learning and understanding the inventory of the imperial collection of the Qianlong emperor’s but also his personal taste. The descriptions also sometimes reveal that his comprehension about ancient ceramics and bronzes could be obsolete and incorrect based on today’s knowledge. For instance, the turquoise enamelled vase seems to be a Kangxi model rather than a Jiajing one as described by the emperor.

Une belle section de textiles sera proposée dont un tapis en soie de la fin du XVIIIe siècle, orné d’une rosace au centre (€20,000-30,000). Egalement une merveilleuse robe impériale en soie brodée à fond abricot, Longpao, de l’époque Xianfeng provenant d’une collection privée européenne. Estimée €40,000-60,000, la couleur abricot était alors réservée aux concubines de second rang de l’empereur ou aux femmes de ses fils, ce qui en fait sa rareté. Provenant de la même collection, un badge de quatrième rang civil rehaussé de plumes de paon datant de l’époque Kangxi se distingue par sa rareté.

Lot 61. Tapis en soie et fils métalliques, Chine du Nord, circa 1890. Dimensions: 256 x 159 cm. (100 ¾ in. x 62 5/8 in.). Estimate EUR 20,000 - EUR 30,000(USD 22,618 - USD 33,927). © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

Il est orné au centre d'une grande rosace rose pâle et deux autres plus petites parmi des rinceaux feuillagés or pâle ponctués de fleurettes sur fond or. L'ensemble est encadré d'un rang de perles et d'une fine bande de grecques or, rose pâle et bleu, puis d'une large bande de fleurs rose parmi les rinceaux feuillagés bleu clair et bleu foncé sur fond or clair.

Note: The central radiating bi-tonal pink flower on the present rug, with its unfurling petals, is often associated with the Buddhist and Hindu esoteric traditions of tantra, while the deptiction of the sacred lotus flower at each end of the field is regarded, especially in eastern religions, as a symbol of purity and enlightenment.

Contemporary Western scholarship has traditionally placed these silk and metallic thread carpets as late 19th or early 20th century based on the dyes and weave. Most carpets woven during the late 19th century are copies of earlier carpets yet there are no known examples of Chinese silk carpets with similar designs, let alone examples with metallic thread, from the 17th century or earlier.

The present example is larger than many and is mostly in excellent condition with an opulent golden metal-thread field, highlighted further by the shimmering golden border filled with lotus flowers and hanging vines. A comparable rug but with a fret-work border was exhibited in Il Drago e il Fiore d'Oro, Museo d'arte Orientale, Turin, December 2015-March 2016, pl. XV, p.92-93. A further example with a similar field design but of much smaller proportions, sold Christie's London, 24 October 2019, lot 260.

Lot 69. Provenant d'une collection privée européenne. Robe impériale en soie brodée à fond abricot, Chine, Dynastie Qing, Epoque Xianfeng (1851-1861). Hauteur: 136 cm. (53 ½ in.) ; Largeur: 184 cm. (72 ½ in.). Estimate 40,000 - EUR 60,000 (USD 45,236 - USD 67,854). © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

Elle est brodée en fils d'or de neuf dragons à cinq griffes au corps sinueux. Les dragons centraux et ceux des manches sont représentés de face, les autres de profil, tous sont à la poursuite de la perle enflammée. Ils entourés des huit emblèmes daoistes, parmi les chauves-souris et les nuages stylisés multicolores sur fond abricot clair. La partie inférieure est ornée de rayures multicolores et des trois terrasses émergeant des flots tumultueux stylisés. Les poignets, les manches et le col sont soulignés de bordures noires brodées également de dragons, de nuages et de vagues, framed.

Provenance: Linda Wrigglesworth Ltd., London, 2006.

Note: Qing dynasty court costume was regulated by the Huangchao liqi tushi (Illustrated Precedents for the Ritual Paraphernalia of the Imperial Court) and the Da Qing Huidian (The Administrative Code of the Qing Dynasty). The laws attempted to control the use of entitlements to restricted colors, fabrics and decorations for specific classes or grades of courtiers. Bright yellow, or minghuang, was reserved for the emperor and his consort. The heir apparent and his consort used xinghuang, or 'apricot yellow', usually orange in tone. The emperor's other sons and their consorts wore jinhuang, or golden-yellow, which had an orange tone that is sometimes difficult to discern from the xinghuang of the imperial heirs.

The apricot color of this magnificent robe was restricted for use by the emperor’s secondary consorts and the wives of his sons, and thus the wearer of this robe could have been one of emperor Xianfeng’s consorts or the wife of one of his brothers. It may have been worn by the Empress Dowager Cixi in 1856, after she was promoted to Yi fei (fourth rank), following the birth of Xianfeng’s only son. Soon after, Cixi was promoted to Yi guifei (third rank), and would have worn a robe of imperial yellow, or minghuang. After the Xianfeng emperor’s death in 1861, Yehe Nara Wanzhen, the primary consort of the Xianfeng Emperor’s brother Prince Chun, was another possible wearer of this robe.

Apricot-colored consorts robes are very rare and few extant example exist. A Xianfeng-period embroidered partially-made apricot 'dragon’ robe in The Linda Wrigglesworth Collection sold in The Imperial Wardrobe: Fine Chinese Costume and Textiles from The Linda Wrigglesworth Collection; Christie’s New York, 19 March 2008, lot 42.

A similar mid-19th century embroidered apricot-ground 'dragon’ robe made for a second or third degree consort or for the wives of the emperor’s sons is illustrated by V. Garrett in Chinese Dress from the Qing Dynasty to the Present, New York, 2007, p. 32, fig. 49.

Lot 68. Rare badge en soie brodée, buzi, Chine, Dynastie Qing, Epoque Kangxi (1662-1722). Dimensions: 35 x 33 cm. (13 ¾ x 13 in.). Estimate 25,000 - EUR 35,000 (USD 28,272 - USD 39,581). © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

Fait pour officier civil de quatrième rang, il est de forme carrée et brodé au centre d'une grue aux ailes déployées perchée au-dessus des flots sur un promontoir rocheux brodé de plumes de paon. Elle est entourée de nuages stylisés multicolores sur fond de fils d'or.

Provenance: Linda Wrigglesworth Ltd., London.

Note: It is rare to find extant examples of civil rank badges dating to the Kangxi period. Fourth rank civil official 'goose’ badges from this period are exceedingly rare.

Most mid- and late-seventeenth century badges have a background of couched gold-wrapped thread, such as seen on the present badge. On early Qing dynasty badges, such as this example, the metallic thread outlines each motif in concentric patterns. The rock has been embroidered with peacock feather filament-wrapped threads and the major motifs are worked in a variety of satin and surface stitches using silk in three strong colors: red, blue and green.

A related goose badge, dated to the late Kangxi period, sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 26 November 2014, lot 3414. Another related Kangxi badge, but decorated with a silver pheasant, was in the Linda Wrigglesworth Collection and sold in The Imperial Wardrobe: Fine Chinese Costume and Textiles from The Linda Wrigglesworth Collection; Christie’s New York, 19 March 2008, lot 28.

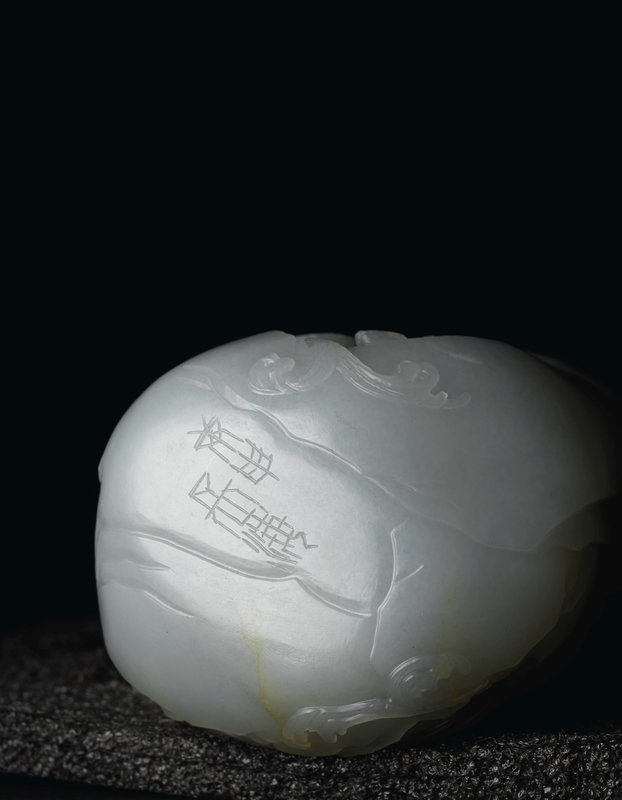

Un superbe ensemble de jades sera également proposé à la vente comprenant un magnifique rocher en jade céladon, datant du XVIIIème siècle, délicatement sculpté du Luohan Abhedya, un disciple bouddhiste lisant un sutra dans une grotte (€30,000-40,000).

Lot 199. Rare rocher en jade céladon pâle, Chine, Dynastie Qing, XVIIIe siècle, Hauteur: 15 cm. (6 in.). Estimate EUR 30,000 - EUR 40,000 (USD 33,927 - USD 45,236). © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

Délicatement sculpté en forme d'une montagne, luohan Abhedya est assis sur un rocher dans une grotte tenant un sutra dans ses mains. Un petit brûle-parfum est placé à sa droite, un grand pin tortueux émerge des parois rocheuses. La base est incisée de plusieurs caractères archaïsants Gengshen Menghai.

Provenance: Christie’s Hong Kong, 1-2 October 1991, lot 1424.

Note: This fantastic jade sculpture depicts an arhat - a Buddhist adept who attained enlightenment - meditating or reading a sutra inside a rocky cave. The current jade boulder depicts the sixteenth luohan, Abhedya. He is shown holding a sutra seated beside an incense burner. A slightly smaller inscribed jade 'luohan and grotto' group (12.8 cm. high) from the Qianlong period in the British Museum, ref 1930.12 -17.15, is illustrated by Jessica Rawson in Chinese Jade, London, 1995, p 410, fig 1. In this book she discusses the origins and significance of this group of 'luohan and grotto' jade carvings. She writes that it is likely that sets of sixteen or eighteen luohan were made and that the subject's popularity during this period may have been boosted by a woodblock print of a jade carving of a luohan amongst rocks from the Gu yu tu pu, attributed to the Southern Song period, but 18th century, and illustrated in Chinese Jade, Fig 2, p 411. Compare with a slightlylarger Qianlong period pale celadon jade 'luohan and grotto' group (16.8 cm high) sold at Christie's Hong Kong, 27 May 2009, lot 1971, another one (22 cm. high) sold recently in Christie's London, 15 May 2018, lot 94.

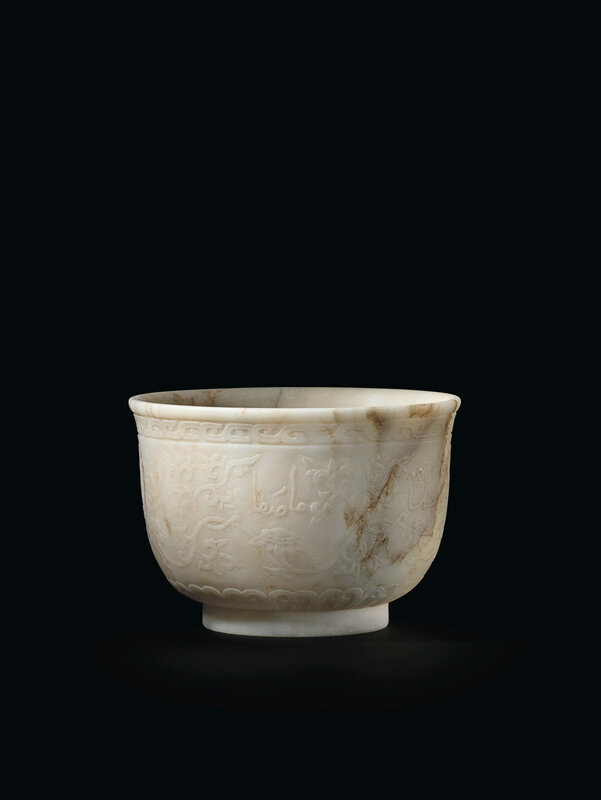

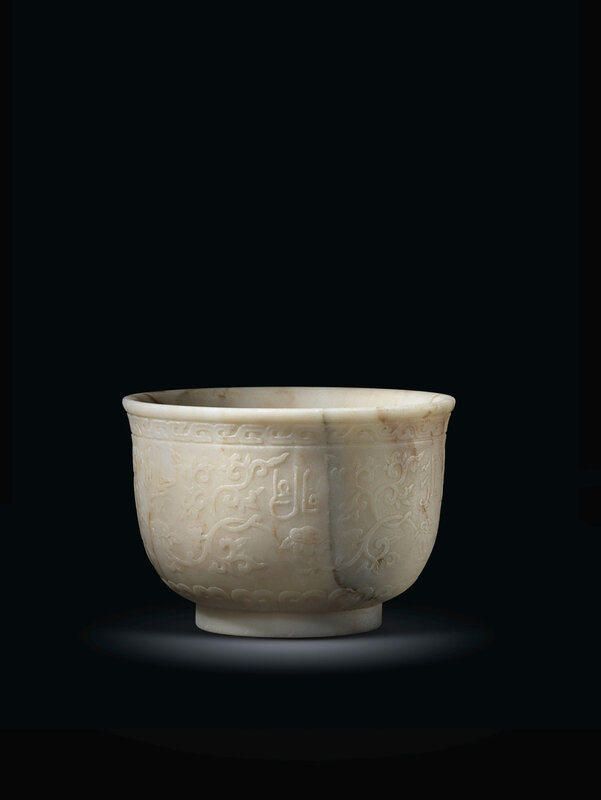

Mentionnons également un élégant bol en marbre blanc de la dynastie Ming sculpté en léger relief et portant une inscription en arabe ma safa min qal wada’ malik rahmat allah ("Quel est le réconfort de ceux qui disent au revoir à la miséricorde d'Allah"), estimé €40,000-60,000.

Lot 203. Bol en marbre blanc, Chine, dynastie Ming, époque Zhengde (1506-1521). Diamètre: 13,9 cm. (5 ½ in.). Estimate EUR 40,000 - EUR 60,000 (USD 45,236 - USD 67,854). © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

Reposant sur un petit pied, sa panse est sculptée en léger relief d'une inscriptions en arabe ma safa min qal wada’ malik rahmat allah ("Quel est le réconfort de ceux qui disent au revoir à la miséricorde d'Allah"). Le col et le pied sont ornés de motifs géométriques.

Note: The inscription reads "ma safa min qal wada’ malik rahmat allah", that may be translated as 'what is the comfort of those who say goodbye to Allah’s mercy’.

Bowls of this form with Arabic inscriptions can also be found on blue and white ceramics from the Zhengde period. It may be compared with a blue and white bowl of similar size in the Palace Museum collection, Beijing, illustrated in Imperial Porcelain from the Reign of the Hongzhi and Zhengde in the Ming Dynasty, Vol II, the Palace Museum and the Archaelogical Research Institute of Ceramic in Jingdezhen, Beijing, 2017, Fig. 208, p 466.

Autre lot important de la vente parmi une sélection d’objets et de thangka tibétain peints ou brodés, un superbe Thangka représentant le mandala de la divinité Cakrasamvara figurant au centre, reconnaissable à sa peau bleue et ses multiples bras (estimation : €50,000 – 60,000).

Lot 57. Thangka représentant le mandala de la divinité Cakrasamvara, Tibet, XVe-XVIe siècle. Dimensions: 84 x 69 cm. (33 x 27 1/8 in.). Estimate EUR 50,000 - EUR 60,000 ((USD 56,545 - USD 67,854). © Christie's Image Ltd 2020.

Au centre sont représentés Chakrasamvara à quatre têtes et à la peau bleue enlaçant sa parèdre Vajravarahi. Ils sont entourés de huit divinités placés dans un palais fermé par quatre portes élaborées. Le tout est compris dans un cercle de flammes et de pétales de lotus. Tout autour sont représentés les Huits Champs de la crémation.

La partie supérieure est ornée de scènes de la vie de Bouddha et de Vajravarahi, la partie inférieure est rehaussée de donateurs et scènes d’offrandes.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F97%2F70%2F119589%2F122219042_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F56%2F57%2F119589%2F122218368_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F09%2F33%2F119589%2F121095122_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F37%2F38%2F119589%2F111451812_o.jpg)