$8.3 million rare Warring States Period Vessel drives Sotheby's bi-annual Asia Week Sales

Lot 578. An Exceptionally Rare and Important Gold, Silver and Glass-Embellished Bronze Vessel, fanghu, Warring States period, 4th-3rd century BC. Height 13¾ in., 35.1 cm. Estimate: 2,500,000 - 3,500,000 USD. Lot sold 8,307,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

NEW YORK, NY.- Sotheby’s bi-annual Asia Week sale series in New York achieved $36.4 million this week – significantly above the series’ high estimate of $29.1 million, and all sales surpassing their high estimates. Works from this season’s sales were sold to a diverse group of collectors worldwide, highlighted by An Exceptionally Rare and Important Gold, Silver and Glass-Embellished Bronze Vessel, which achieved $8.3 million following a 12-minute bidding battle and was the top selling lot of the week. Below is a summary of the works and collections that drove these results.

Angela McAteer, Sotheby’s Head of Chinese Works of Art Department in New York, commented: “We are thrilled with the results from this week’s sales of Chinese Works of Art. The strong results demonstrated the powerful and continued strength of the Chinese art market, and showcases the extraordinary array of works offered across categories– including Kangxi porcelain; Chinese jades; early ritual metalwork; Buddhist bronzes and more – most of which have not been seen by the market for many decades. We saw active and deep bidding activity across sales, representing a truly international clientele. It was especially exciting to once again hold our Asia Week sales in our New York salesroom, and we look forward to continued success in March next year.”

Anu Ghosh-Mazumdar, Sotheby’s Head of Indian & Southeast Asian Art Department in New York, said: “As we commemorate our 35th year of Indian, Himalayan & Southeast Asian Works of Art sales in New York, we were proud to present a sale of exceptional works, led by a discovery piece - A Gilt Copper Figure Of Avalokiteshvara formerly in the legendary collection of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and emerging for the first time in nearly a century. We are delighted that this masterpiece will now occupy pride of place in a distinguished private collection. Throughout the sale, we saw active bidding from across the world, and yesterday’s success indicated the market’s support for high quality artwork.”

KANGXI PORCELAIN – A PRIVATE COLLECTION

Auction Total: $4.5 Million

The exquisite collection of Kangxi porcelain kicked off Asia Week with a thrilling start, as the first three works offered each generously exceeded their high estimated by multiple times, and saw deep bidding activity for each lot. The auction achieved $4.5 million – exceeding its high estimate of $3.1 million.

The group was led by A Rare Peachbloom-Glazed 'Chrysanthemum' Vase, which fetched $746,000 – nearly five times its high estimate of $150,000. Known as juban ping, 'chrysanthemum petal vase', this piece is remarkable for its well-balanced form and delicate rose-pink glaze. The technological and artistic advances created during the Kangxi reign at the imperial kilns in Jingdezhen are illustrated in the present vase. Of all the innovative forms developed in the Kangxi period, chrysanthemum vases were perhaps the most influential, as they inspired the numerous chrysanthemum-shaped vessels of the succeeding Yongzheng reign.

Lot 116. A rare peachblom-glazed 'chrysanthemum' vase, Kangxi mark and period (1662-1722); Height 8¼ in., 21 cm. Estimate: 100,000 - 150,000 USD. Lot sold 746,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

Cf. my post: A rare peachblom-glazed 'chrysanthemum' vase, Kangxi mark and period (1662-1722)

JUNKUNC: CHINESE JADE CARVINGS

Auction Total: $6.3 Million

A selection of more than 60 jades on offer from the renowned collection of Stephen Junkunc, III achieved $6.3 million, surpassing the auction’s $5 million high estimate. The sale marks the continued success of the Junkunc Collection, which has raised over $28 million across Sotheby’s auctions since 2018.

Following an eight-minute bidding battle, an exceedingly rare Large Yellow and Russet Jade Carving of a Mythical Beast realized $1.7 million – more than five times its high estimate of $300,000. Outstanding for the playful yet dynamic rendering of the mythical beast and its impressive size, this carving successfully captures the supernatural vitality of the creature. The notched spine and muscular body which is poised as though ready for action, along with the pronounced eyes and curled features such as its beard, tail and ears, display the technical expertise of its carver. Highly tactile in its smooth finish and impeccably modeled in the round, this carving would have been particularly favored by the jade connoisseur.

Lot 227. A Large Yellow and Russet Jade Carving of a Mythical Beast, Qianlong period (1736-1795). Length 5⅞ in., 15 cm. Estimate: 200,000 - 300,000 USD. Lot sold 1,714,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

well carved, crouching on its four powerful legs as if preparing to pounce, its head turned gently to the left, detailed with a short, curled pointy beard, a long snout, bulging eyes, and a finely incised mane flanked by a pair of large furled ears, its pronounced ridged spine terminating in a long bushy tail swept against the right haunch, the softly polished stone of greenish-yellow tone with some areas of russet coloration and occasional natural fissures, wood stand (2)

Provenance: Collection of Stephen Junkunc, III (d. 1978).

Note: Outstanding for the playful yet dynamic rendering of the mythical beast and its impressive size, this carving successfully captures the supernatural vitality of the creature. The notched spine and muscular body which is poised as though ready for action, along with the pronounced eyes and curled features such as its beard, tail and ears, display the technical expertise of its carver. Highly tactile in its smooth finish and impeccably modeled in the round, this carving would have been particularly favored by the jade connoisseur.

The development of sculptures of mythical creatures occurred during the Han dynasty (206 BC-220 AD) when they began to appear in large numbers in durable materials, such as stone and jade. They were placed along the path to, and inside, tombs to pacify the elemental and supernatural forces of the world. This tradition further flourished during the Six Dynasties when immense fabulous beasts drawn from the spiritual world were produced on a grand scale outside the tombs near Nanjing. Simultaneously, an artistic tradition of creating jade animals of this type, but on a smaller scale, emerged. In contrast to the earlier two-dimensional jade carvings made for the afterlife or to adorn the individual, these creatures were modelled in the round as artistic objects and to provide the owner with a constant and concrete realization of the powerful supernatural forces in the world. As a result, carvings of mythical creatures continued to abound throughout Chinese history, of which the present is an exquisite example.

A number of carvings of recumbent mythical creatures rendered in a similar stylized manner include a closely related example, but with the head turned, published in Compendium of the Cultural Relics in the Collection of the Summer Palace, Beijing, 2018, pp 98-99 (fig. 1); and a smaller forward-facing version, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, included in Denise Leidy et. al., 'Chinese Decorative Arts', The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Summer 1997, p. 25.

A Yellow and Russet Jade Carving of a Mythical Beast, Qianlong period (1736-1795), , published in Compendium of the Cultural Relics in the Collection of the Summer Palace, Beijing, 2018, pp 98-99.

Compare also the exaggerated facial features and body of a jade mythical creature, in the Qing Court Collection and still in Beijing, included in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum. Jadeware III, Hong Kong, 1995, pl. 93; another, attributed to the Ming period, published in Jadewares Collected by Tianjin Museum, Beijing, 2012, pl. 173, together with a seated version, pl. 172; another sold at Christie's Hong Kong, 3rd June 2015, lot 3188; and another, from the Muwen Tang Collection, sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 1st December 2016, lot 38.

INDIAN, HIMALAYAN & SOUTHEAST ASIAN WORKS OF ART

Auction Total: $3.3 Million

The afternoon closed with a thoughtfully curated collection of superlative examples of Himalayan sculpture, superb Southeast Asian & Indian sculptures, and fine Indian miniature paintings, totaling $3.3 million. The auction was led by A Gilt Copper Figure of Avalokiteshvara dating to the 9/10th-century from Nepal that achieved $830,700 – surpassing its $500,000 high estimate. A rare discovery piece, the work appeared on the market for the first time in nearly a century, after it was last acquired by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller in 1922. Other highlights in the sale included an exquisitely carved 12th Century Pala stone sculpture of Surya from a private Japanese Collection that soared past its $50,000 high estimate and sold for $126,000. A beautifully crafted 17th Century Tibetan silver image of the revered Fifth Sharmapa shattered its $50,000 high estimate to achieve a price of $252,000. Indian paintings in the sale performed particularly well, with a rare 18th Century scene of A Nawab and his Retainers in Procession from Murshidabad selling for $88,200 against its $50,000 low estimate and a similarly rare, large 18th Century watercolor of the View of the River Ganges near Currah by artist William Daniell which sailed past its $60,000 high estimate to achieve $100,800.

Lot 322. A Gilt Copper Figure of Avalokiteshvara, Nepal, 9th-10th-century. Height 10 ½ in. (26.7 cm). Estimate: 300,000 - 500,000 USD. Lot sold $30,700 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the bodhisattva of compassion seated on a wide lotus petal throne, the top incised with the motif of lotus pods, luxuriously positioned in sattvaparyankasana, wearing a shawl drawn across the body and falling in pleats over the left shoulder, the dhoti held in place by an ornamented waist band wrapping around the legs in a chased striated pattern, with gem set armbands set high on the shoulders, a necklace with attached pendants, and lotus-form earrings resting on the shoulders, the left hand supporting his weight from behind and holding the stalk of a lotus that follows the curve of the arm with a lotus blossoming over the left shoulder, the head encircled in an aureole decorated in swirling flames

Himalayan Art Resources item no. 13744..

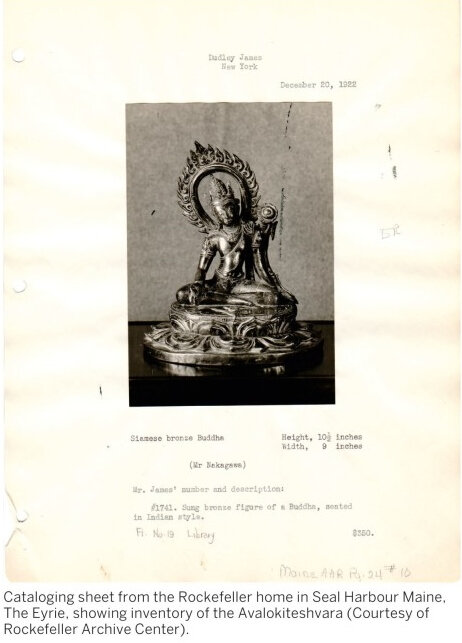

Provenance: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, acquired from Dudley James, New York, 1922.

Note: From the seat of a lotus throne, Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion, outstretches his hand in the gesture that signifies benevolence and charity. A principal deity that arose in tandem with the teachings of Mahayana Buddhism, Avalokiteshvara expresses the foundational tenets of the religion by postponing his own enlightenment in order to continually guide others into liberation from suffering. His earthly activity is shown in his princely attire of crown and jewelry and his relaxed posture, while simultaneously his inward meditative gaze and the Buddha Amitabha standing in effigy in his crown suggests his spiritual transcendence. Like the stalk of the lotus rising from his left hand and blooming over his shoulder, Avalokiteshvara arises from the murky waters of existence as a pure and perfect being.

The Mahayana tradition of Buddhism gained prominence in India during the Gupta Empire, and after the Licchavis’s political matrimony with the Gupta rulers had collapsed, they left India carrying Indic culture and religious practices with them into the Kathmandu Valley. Avalokiteshvara, colloquially known in Nepal as Padmapani, “Lotus Holder”, was assimilated into the Newari culture beginning in the 6th Century, and carried a popularity superseded only by the Buddha. Over time, the impassioned worship of the deity in the local culture gave rise to a visual syncretism, blending the initial influences of the Gupta dynasty and Pala dynasty into a more distinctive Newari style. Later depictions show the deity standing, hips swaying to the side, in the most recognized and repeated form of the deity in Nepal. The present sculpture, though, is a rare and early example showing the dominating features of the Gupta and Pala styles as they made their way into the expert hands of Newari metalworkers.

The Gupta dynasty, spanning the 4th to the 6th centuries, was known for its sensual features and harmonious contours which strongly influenced Nepalese artistic traditions. Two examples of Gupta style bronzes, both standing images of the Buddha (see U. von Schroeder, Indo-Tibetan Bronze, Hong Kong, 1981, pl. 45E and the Metropolitan of Art (acc. no. 69.222)), allude to the same naturalistic flexion of the body as depicted in the Nepal Padmapani. All show a taut musculature around the torso – an assured physicality that captures the fluid and graceful rendering of the body portrayed during the Gupta dynasty. Quiescence and introspection characterizes the face and can be compared to the standing Sarnath figure of Khasarpana Avalokiteshvara in the National Museum in Delhi (see S. L. Huntington, The Art of Ancient India, New York, 1985, pl. 10:22) In each a remote and inwardly thoughtful expression is emphasized by broad arching eyebrows over wide lowered lids, prominent aquiline noses as well as protruding lower lips with softened corners.

Standing Buddha Offering Protection, Gupta period, late 5th century, India (Uttar Pradesh, Mathura). Red sandstone. H. 33 11/16 in. (85.5 cm); W. 16 3/4 in. (42.5 cm); D. 6 1/2 in. (16.5 cm). Purchase, Enid A. Haupt Gift, 1979, 1979.6. © 2000–2020 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Buddha Offering Protection, Gupta period, late 6th–early 7th century, India (probably Bihar). Copper alloy. H. 18 1/2 in. (47 cm); W. 6 1/8 in. (15.6 cm); D. 5 5/8 in. (14.3 cm). Purchase, Florance Waterbury Bequest, 1969, 69.222. © 2000–2020 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The later Northeastern influences from the Pala dynasty overlay the lithe contours of the Gupta style with decorative features, adding richness, movement and ornamentation. A 9th Century Pala Avalokiteshvara from the Nalanda Museum (N. Ranjan Ray, Eastern Indian Bronzes, India 1986, pl. 86) shows an identical crown style – the tripartite diadem with a smaller central ornament allowing for the coiffure of matted hair to accentuate the effigy of Buddha Amitabha as the principle focus. Moreover, the styling of the robes, particularly the draping folds over the left shoulder, the armbands placed high up along the arms and the flaming halo behind the head show resonances closely linked with the Nepal Padmapani. Another Pala bronze depicting Vajrapani in the National Museum in Delhi (acc. no. 47-38) shows corresponding treatment in the striped pattern of the dhoti, the styling of the waistband with a rosette clasp and a similar wide circular shaped base incised with lotus pods.

Vishnu Flanked by His Personified Attributes, Pala period, early 9th century, India (Bihar). Bronze. H. 20 3/4 in. (52.7 cm). Gift of Florence and Herbert Irving, 2015, 2015.500.4.10. © 2000–2020 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Late Licchavi works, such as the Nepal Padmapani, although heavily relying on their Indian counterparts, are consummately fashioned with the adeptness of Newari metalworking techniques. The Padmapani shows a harmony amongst all its elements, a skill mastered by the Newari craftsmen. A seated Maitreya of the same period (see P. Pal, The Sensuous Immortals: A Selection of Sculptures from the Pan-Asian Collection, Los Angeles, 1977, fig. 95A), equally features a unifying effect between the contouring of the body, patterning of incised lines and ornamental details. The warm tones of the copper and thin layering of gilding on top, indicative of the Newari craft, renders the piece with a rich and luxuriant glow.

Seated Maitreya, Nepal, , 9th-10th-century, in J. Casey, Et Al., Divine Presence: Arts of India and The Himalayas, 2003, p. 106-107, pl. 28.

In effect, Padmapani shows a naturalism that balances multiple extremes: expression and restraint; movement and stillness; earthiness and transcendence. This equilibrium can be seen in every feature of the piece. The supple flesh of the fingers open out, while the thumb stays folded towards the palm. The body gently sways to the side while the head gently tilts in the opposite direction. The lotus leaves of the wide base open fully along the bottom, but their tips delicately curl back towards the deity. The flames around the halo swirl with energy but all move in the same direction, framing the tall crown and face of Avalokiteshvara. The lotus stalk rises and contours the curve of the figure’s arm, while the fully bloomed lotus rests over the deity's shoulder. The subtle play between these elements and each other draws the viewer, or what would have been a devotee, into a rich atmosphere of both warmth and serenity.

Left to right: Abby Aldrich Rockefeller and John D. Rockefeller Jr.; The Eyrie (images courtesy of The Rockefeller Archives).

This sculpture was purchased in 1922 by Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, at a time when little was known of Nepal or the Kathmandu Valley in the West. This is clear from the 1922 invoice, where it is described as a “Sung bronze Figure, seated in Indian style”. It is likely that the Padmapani was transported, as many images from Nepal were, to Tibet, and eventually into China. We know from the Rockefeller Archives that our Padmapani was originally housed in The Eyrie, a summer home built by John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1910 in Seal Harbour Maine, which no longer exists.

Lot 350. A black stone stele depicting Surya, India, Pala period, 12th Century. Height 33 in. (84 cm). Estimate: 30,000 - 50,000 USD. Lot sold 126,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

standing in sampada and holding two lotus flowers, wearing a diaphanous pleated dhoti, beaded upavita, foliate collar, circular ear ornaments, the bearded Pingala to his right and the youthful Danda to his left, rampant viyalas trampling elephants in the side panels, two flying apsaras bearing garlands flanking a kirttimukha mask above, the faceted pedestal carved showing the seven horses drawing his celestial chariot.

Provenance: Collection of a Japanese Diplomat, acquired in Bangladesh in the early 1970s.

Note: The sun god here is represented in his characteristic frontal posture, the deity dominating the composition, surrounded with his many attendants. Surya is displayed with the characteristic richness and detailed elaboration of the style as seen in later Pala stone sculptures. For another example showing Surya with ornate detailing, see S.L. and J.C. Huntington, Leaves from a Bodhi Tree: The Art of Pala India (8th-12th centuries) and Its International Legacy, Seattle, 1990, cat. 40.

Lot 311. A silver figure of the Fifth Sharmapa, Konchok Yanglak, Tibet, 17th century. Height 7 ⅞ in. (20 cm). Estimate: 30,000 - 50,000 USD. Lot sold 252,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the lama seated in meditation posture on a cushion base, with the right hand resting on his knee and the left hand holding a flaming jewel, wearing robes of a monastic decorated with incised borders of clouds and foliate patterns, his eyes cast downward in meditative concentration, the red hat of the Shamar lineage crowning his head, showing the three-jeweled emblem illustrated on the front flanked by cloud patterns and topped with the crescent sun and moon pattern above.

Himalayan Art Resources item no. 13715.

Provenance: William H. Wolff, Inc., 1977.

Note: The inscription at the base of the sculpture identifies this figure as the Fifth Sharmapa, Konchok Yanglak: ‘Homage to the red hat holder Konchok Yanglak! Mangalam’ (ཞྭ་དམར་ཅོད་པན་འཛིན་པ་དཀོན་མཆོག་ཡན་ལག་ལ་ན་མོ་མངྒ་ལཾ།). The Fifth Sharmapa (1525 - 1583) was born in the Kongpo district and formally enthroned by the Eighth Karmapa, Mikyo Dorje (1507–1554) as the reincarnate of the red hat lineage. Having completed his studies by the age of twelve, "his fame for learning, discipline, and kindness soon spread widely." (D. P. Jackson, Patron and Painter: Situ Panchen and the Revival of the Encampment Style, p 90) It was the Fifth Sharmapa who later led the enthronement of the Ninth Karmapa, Wangchuk Dorje (1556-1603) and furthermore, served as his primary teacher.

In addition to his scholastic and spiritual accomplishments, the Fifth Sharmapa involved himself in building programs of temples and the commissioning of sacred art, supporting the artist Namkha Tashi, the founder of the Gardri painting school.

Konchok Yanglak's portrait is recognizable in paintings and sculpture alike from his slender physique, his elongated oval shaped face and enlarged ears. Here, cast in silver, a rare choice for Tibetan portraits, the Sharmapa is shown in meditation seated poised on a wide cushion with his left hand cradling a flaming jewel. In another example illustrated on Himalayan Art Resource, item no. 65561, the Fifth Sharmapa similarly holds a triratna in his left hand.

A 16th/17th Century portrait from the Nyingjei Lam Collection also portrays the Sharmapa in a silver cast. As noted by Weldon and Casey, the primary examples of silver cast portraits are of the Kagyu order, seeming to suggest their preference for this particular style of casting. (D. Weldon and J. C. Singer, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet, pl. 49, p. 190). Another silver cast depicting the Ninth Karmapa, Wangchuk Dorje (1554-1603) (ibid., pl. 48) and showing similarity in style is dated by inscription to 1598.

Lot 368. A Nawab and his Retainers in Procession, India, Murshidabad, circa 1760-1770, Opaque watercolor on paper heightened with gold, image: 10 ⅛ by 13 ⅛ in. (25.7 by 33.3 cm), folio: 10 ¾ by 13 in. (27.31 by 33 cm), unframed. Estimate: 50,000 - 70,000 USD. Lot sold 88,200 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

Provenance: Gifted by Stuart Cary Welch, circa 1966.

Note: This rare and remarkable painting depicts a stately procession slowly making its way across a landscape bearing timeless vignettes of rural Bengal, rendered in infinite detail.

In the foreground farmers plow their fields and tend their crop while herds of cows and goats graze serenely. The procession itself is seen at the center of the picture, moving from left to right in a dignified cadence with a nawab on a canopied elephant accompanied by riders on horseback, soldiers on foot, noblemen on caparisoned elephants and horseback and even a pair of camels at the front of the train. At the center is a cloth covered litter no doubt bearing a precious cargo of noble ladies, sheltered from prying eyes. The palanquin is surrounded by a throng of attendant figures bearing swords and shields and dressed in fine white muslin jamas, ubiquitous in the humid climate of Bengal. Riders at the front of the train point spears at a target off-scene, as a horseman gallops forward on the right. One of the horsemen bringing up the rear holds a banner with a meen a’lam or fish-shaped standard.

Above the procession, on the upper left, are a group of figures, so delicately drawn as to be barely discernible, sheltering from the midday heat in a grove of shady trees. In the farther distance hunting preparations take place near a pond filled with waterfowl. Beyond gently sloping hills, tall palm trees, some with bent trunks, break the horizon line, with puffy clouds floating beyond.

This extremely fine painting from Murshidabad displays elements of naturalism – evidenced in the detailed depiction of the land and people – as well as perspective, with the elements of the landscape disappearing to a vanishing point. Another very similar composition, possibly by the same artist(s), from the Stuart Cary Welch Collection, was sold at Sotheby's London, May 31, 2011, lot 109. For two other relatable examples in the British Library, London, see T. Falk and M. Archer, Indian Miniatures in the India Office Library, London, 1981, pps. 200 and 489, cat. 374 i & ii.

Robert Skelton in a personal correspondence has remarked that the style of this artist/workshop recalls the work of Dip Chand. Based on the historical record we might surmise that the Nawab pictured herein is Najm ud-daula, son of Mir Ja'far, who ruled as a dedicated British vassal. For another painting from Murshidabad now in the collection of the Chester Beatty Library, Dublin, see L. Leach, Mughal and other Paintings from the Chester Beatty Library, London, 1995, vol. 2, no. 7.103, pp. 768, 788-9

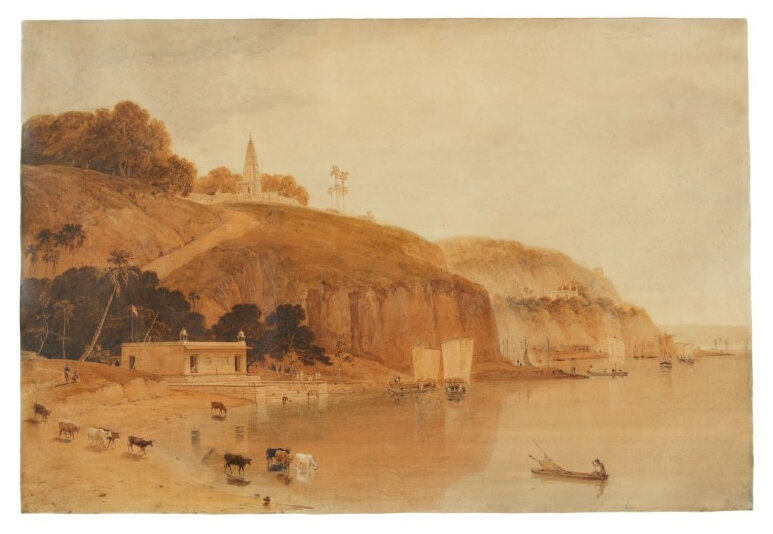

Lot 382. William Daniell, View of the River Ganges near Currah, December 1788. Watercolor on paper.Signed 'W Daniell Jan. 7, 1804' lower left, 25 ¼ by 37¼ in. (64.1 by 94.6 cm). Estimate: 60,000 - 80,000 USD. Lot sold 100,800 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

Provenance: Reg and Philip Remington, London, 1993.

Note: The large watercolor picturing a serene riverbank with a group of cows ambling down to the water’s edge in the company of bathers at a nearby ghat. Sailboats hug the winding riverbank while a fisherman paddles nearby. Beyond a copse of trees behind the ghat is a winding road leading up to a temple on the bluffs above. The scene is set on the banks of the Ganges near the Fort of Kara (Currah).

This marvelous watercolor by the English artist William Daniell, was painted during his trip to India in the years 1786-94 accompanied by his uncle and collaborator Thomas Daniell (1749-1840) who was a member of the Royal Academy. Notable was their celebrated series of 144 aquatints "Oriental Scenery" published in six parts in London from 1795 to 1807, which was based upon their depictions of picturesque Indian landscape views executed in watercolor and pencil sketches. William Daniell was elected a full member of the Royal Academy on February 9, 1822.

The two artists often took notes of their observations and recorded these in their diaries. Regarding Currah, Daniell noted, "The banks of the Ganges are here very lofty, steep, and picturesque; but are subject to considerable alterations in the rainy season, as the river then rises to the height of thirty feet.”

Mildred Archer mentions that, "Kara was a sacred place in early Hindu days. It was conquered by the Muslims in 1194 and became a seat of government until the present fort and city of Allahabad were built by Akbar in 1583 as the new administrative centre. Ruins of the old city extended along the river bank for 2 miles." (M. Archer, Early Views of India, London 1980, no. 26)

Very relatable scenes in aquatint were published by the Daniells as follows: "Near the Fort of Currah on the River Ganges," Plate 18 (dated 1801) and Plate 21 (dated 1796) from "Oriental Scenery. Twenty Four Views In Hindoostan" By William and Thomas Daniell (Royal Academy 18/2381).

An oil painting of a related scene by William Daniell was sold at Christie’s London, September 27, 2001, lot 10, signed and inscribed with an old label on the verso: "Near Curah Manickpore on the Ganges - with native females carrying away the water from the sacred stream - W. Daniell R.A." Pencil and watercolor sketches of Currah were featured in the same sale as Lots 3 and 4.

The present large watercolor is one of the finest and most atmospheric of Daniell's renderings to appear at auction. For further reference on scenes from India painted by Thomas and William Daniell, see B. N. Goswamy, Daniells’ India: Views from the Eighteenth Century, New Delhi, 2013.

IMPORTANT CHINESE ART

Auction Total: $22.4 Million

This season’s various-owner sale of Important Chinese Art totaled $22.4 million – well-exceeding its $16.9 million high estimate. The auction was led by An Exceptionally Rare and Important Gold, Silver and Glass-Embellished Bronze Vessel, which sold to applause for $8.3 million – more than double its $3.5 million high estimate, following a 12-minute bidding battle between five bidders. Individually designed and likely created for a royal patron, the present fang hu was formerly in the collection of Belgian industrialist, banker and famous art collector Adolphe Stoclet. Representing the peak of luxury in the Warring States period, vessels decorated in the most ambitious and flamboyant style ever devised for Chinese bronzes are so exceedingly rare that the technique is virtually unknown, and almost nothing has been published about this important aspect of the bronze craft, since examples are impossible to see. The present bronze is therefore of major importance for the history of Chinese bronzes, metal technology, and glass making.

Lot 578. An Exceptionally Rare and Important Gold, Silver and Glass-Embellished Bronze Vessel, fanghu, Warring States period, 4th-3rd century BC. Height 13¾ in., 35.1 cm. Estimate: 2,500,000 - 3,500,000 USD. Lot sold 8,307,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

of square section, set atop a straight foot with the swelling belly rising to a slightly flaring neck and surmounted by a slightly domed cover set with four bird-shaped finials, each side of the vessel decorated with a complex design of diamond-shaped glass plaques set into cast recesses of conforming shape, surrounded by wide bands of enlaced lines and volutes inlaid in silver, with raised circular bosses embellished with gold-sheet set at regular intervals, on two sides the shoulder set with an animal mask handle suspending a loose ring, with glass plaque and silver inlay, and raised bosses, the dark brown patina with green malachite encrustation (2).

This bronze vessel with its embellishments in gold, silver and polychrome glass, individually designed and created probably for some royal patron, must have represented the peak of luxury in the Warring States period (475-221 BC). Vessels decorated in this most ambitious and flamboyant style ever devised for Chinese bronzes are so exceedingly rare, that the technique is virtually unknown and almost nothing has been published about this important aspect of the bronze craft, since examples are virtually impossible to see. Of only three other known bronze vessels with related glass inlays, only one piece, excavated in China, but of slightly later date, has been made widely public and has thus become famous; the other two came onto the market around 1930, entered Japanese collections, but have hardly been publicly shown ever since. The present piece, too, has not been published or exhibited since 1938. Connoisseurs of Chinese art and even specialists in archaic Chinese bronzes may therefore feel they have never seen anything like it.

Inlaid bronzes began to be made in the Spring and Autumn period (770-476 BC). While the early copper inlays that were added to the mold before the bronze was cast, were limited to fairly stiff cut-out silhouettes, other techniques were soon experimented with in order to create more vivid designs. The preferred method became incising into the bronze after casting, where the grooves were then filled with precious metals. The present piece is inlaid with complex silver designs, consisting of lively enlaced lines and volutes. They can be seen as the bronze craftsmen’s masterful answer to the concurrent fashion for fluid painted decoration on contemporary lacquer wares, which are here superbly echoed in bronze.

The gold bosses of our vessel were created by applying rather thickly hammered sheet gold onto raised knobs, rather than through mercury gilding, as was quite commonly used at the time, but which would have added only a much thinner layer of the precious metal. The bosses themselves appear to have been separately added to the cast bronze before being covered with gold.

In addition to the use of gold, silver and copper to enrich the monochrome bronze surface, Warring States vessels were sometimes inlaid with pieces of malachite and turquoise which provided bright color, but were very small. Much more successful in adding color and sparkle was the inlay with polychrome glass plaques. Yet it was clearly also the most complex and demanding method, not only on account of the extreme rarity and preciousness of glass at the time, but also because it required the cooperation of artisans working in very different media, versed in different techniques that required different skills. To receive the glass plaques, the bronze was cast with specially shaped recesses, which explains the walls’ unusual thickness and the vessel’s remarkable weight. The glass plaques then had to be created to fit.

Glass was still hardly in use at the time, known mainly in form of imported beads, and undoubtedly an extravagant choice for embellishing a bronze. Glass beads with ‘eye’ motifs in contrasting colors had been made particularly in Egypt but also in many other Central, Middle, Near Eastern and Western countries from the mid-second millennium BC onwards and were universally popular as talismans. At least since the Warring States period, some of these foreign beads had found their way into China, and it did not take long before they were reproduced locally. At first, they were perhaps copied in form of pottery beads with inlaid glass ‘eyes’, but soon as pure glass ‘eye beads’.[1] Visually, Chinese glass beads are difficult to distinguish from those made abroad, but since they differ in composition, chemical tests have confirmed that both existed side by side in the Warring States period.

The present bronze with its application of gold and silver and its lavish use of ‘eye’-decorated glass plaques is therefore not only of major importance for the history of Chinese bronzes and Chinese metal technology, but equally for the history of Chinese glass making. Its triangular and lozenge-shaped plaques with contrasting ’eye’ patterns must have been custom-made near the bronze foundry to suit the requirements of the vessel. They were specially designed, not only in order to fit in shape, but also in design: the usually circular or oval white inlays defining the ‘eyes’ were here turned into lozenges and triangles that evenly fill the surface of the angular or pointed glass plaques. By creating a geometric pattern that no longer immediately evokes eyes, the Chinese craftsmen freely adjusted the foreign style to suit their own purpose.

The closest vessels known to exist are a pair of hu of similar date and style, recorded as having been excavated at Jincun near Luoyang in Henan province, where important works of the late Warring States period were excavated around 1930, and are since preserved in Japan. These two vessels, which are larger (probably 42.5 cm, but published figures vary) and of circular section, are decorated in a very similar way with an overall diaper design with gold bosses and silver designs and lozenge-shaped and triangular glass ‘eye plaques’, although the latter show more complex floral patterns. These important works of art are both known from old photographs only and are virtually unknown outside Japan. Both were originally in the collection of Asano Umekichi, Osaka. One has been designated ‘Important Cultural Property’, entered the collection of Baron Hosokawa Moritatsu and is now in the Eisei Bunko, Tokyo (fig. 1).[2] The subsequent history and present whereabouts of the companion jar are unknown (fig. 2).[3] Yūzō Sugimura describes the Hosokawa jar as “An example of the finest workmanship of late Chou [Zhou] times, probably a family treasure of one of the kings or feudal rulers of the time”.[4] Max Loehr, in discussing “this dazzling, round Hu”, suggests as its date the period between about 500 and 300 BC.[5]

Fig. 1. A gold, silver and glass-embellished hu, Warring States period. © Eisei Bunko, Tokyo.

Fig. 2. A gold, silver and glass-embellished hu, Warring States PERIOD AFTER Umehara Sueji, rakuyō Kinson Kobo Shūei/Selection Of Tomb Finds From Lo-Yang, Chin-Ts’un, Kyoto, Rev. Ed. 1944, Pl. 18.

The third comparable vessel known to have survived is probably of slightly later date: the famous royal gilt and silvered bronze jar with glass inlays from the tomb of Liu Sheng, Prince Jing of Zhongshan, who died in 113 BC (fig. 3). This massive vessel, now in the Hebei Provincial Museum, Shijiazhuang, nearly 60 cm high and weighing 16.25 kg, is considered unique. It is gilded and silvered, shows silver bosses at the intersections of its diaper design and is also inlaid with lozenge-shaped and triangular glass ‘eye plaques’.[6] Liu Sheng was a son of the Western Han Emperor Jing Di (r. 154-141 BC) and himself ruled over Zhongshan principality. He was most lavishly buried in a jade burial suit in a sumptuously appointed tomb in Mancheng county, Hebei province, and his glass-inlaid bronze hu is inscribed with a palace name.

Fig. 3. Gilt and silvered bronze jar with glass inlays, excavated in the Mancheng Han tombs. Western Han dynasty. Hebei Museum, Hebei. Photography by Zhang Hui.

Chinese glass beads have been discovered at some of China’s most prestigious archaeological sites of the Warring States period. A series of beads with an ‘eye’ pattern formed of blue dots enclosed by dark brownish rings, on fields of white that are set into a turquoise-blue ground, very similar to the design on the glass plaques of our fang hu, has been found, for example, in the important fifth-century BC tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng at Leigudun, Suixian, Hubei province (fig. 4).[7] Glass pieces other than these foreign-inspired beads were exceedingly rare in the Warring States period. This type of polychrome glass (liuli) with inlaid ‘eye’ and related patterns was in China made for an extremely short period and obviously enjoyed very high prestige.

Fig. 4. Glass beads, excavated from the tomb of Marquis Yi of Zeng, Warring States period. Hubei Museum, Hubei.

Experiments were also made with inlaying glass paste into pottery to create replicas of glass-inlaid bronzes such as the present vessel, probably at the fraction of the cost.[8] Surviving examples are, however, also extremely rare. Those that exist, like a jar in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (fig. 5),[9] show related grid designs with bosses at the intersections. These glass-paste pottery vessels in turn are believed to be the direct antecedents of China’s lead-glazed ceramics.

Fig. 5. Covered jar (guan), Qin dynasty, 3rd century B.C. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Bequest of Charles Bain Hoyt -- Chales Bain Hoyt Collection. 50.1841. Photograph © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Glass was employed much more frequently from the Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220) onwards, but then mostly monochrome glass (boli) was produced that could be used in place of jade or other colored stones. Minor glass inlays in form of small monochrome dots simulating semi-precious stones are also found on a few bronze vessels: A hu without cover, for example, inlaid in a very different style with gold, silver, turquoise and small circular pieces of red glass probably meant to simulate agate, was excavated in Baoji, Shaanxi, and is now in the Baoji Municipal Museum; [10] and a silver-inlaid egg-shaped bronze dui tripod in the British Museum, London, is also believed to have featured small dots of glass.[11] Glass inlays are otherwise known only from small bronze objects such as belt hooks. Since this much simpler form of glass was used to replicate more expensive materials, its prestige in the Han dynasty waned.

The basic shape of our fang hu is well known from late Warring States and early Western Han (206 BC – AD 9) bronzes, although its depressed, bulging proportions and its pointed, pyramidal cover are unusual. A pair of fang hu of more elongated form and with pyramidal covers with a flat, ‘cut-off’ tip, also decorated with diaper designs arranged around gold bosses, were inlaid with niello and originally perhaps semi-precious stones but no glass; one of them, from the collection of Eric Lidow is now in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (fig. 6)[12], the other, from the collection of Arthur B. Michael and later in the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, New York, was sold in our New York rooms, 20th March 2007, lot 508 (fig. 7).[13] Another related fang hu without cover, also with metal-inlaid diaper design but with less prominent gold bosses, is in the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco (fig. 8),[14] and a very similar vessel is depicted in a woodblock illustration in the catalogue of bronzes in the imperial collection compiled for the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-1795), Xi Qing gu jian (fig. 9).[15]

Fig. 6. Lidded square wine storage jar (fang hu) with lozenges and knobs, Late Eastern Zhou dynasty, Early or Middle Warring States PERIOD, about 481- 300 B.C. Courtesy of Los Angeles County Museum, Los Angeles.

Fig. 7. A rare copper-inlaid archaic bronze wine vessel with gilt bosses (fang hu), Warring States period, 4th century B.C. Sotheby’s New York, 20th march 2007, lot 508.

Fig. 8 Ritual Wine vessel (fang hu), prob. 400–300 BCE. China. Warring States period (c. 475–221 BCE). Bronze with copper, gold, silver, and stone inlays. Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, The Avery Brundage Collection, B62b38. Photograph © Asian Art Museum of San Francisco.

Fig. 9, Liang Shizheng Et Al., Xi Qing Gu Jian, 1755, Vol. 20: Hu, No. 22.

Sacrificial bronze vessels were of very high importance in Zhou (1045-221 BC) society. They were used during sacrificial ceremonies to offer food and wine to the ancestors to obtain their protection. As the offerings were subsequently jointly consumed at ritual banquets, they also served to bond family clans. A vessel such as the present fang hu might have been used to contain wine in such ceremonies that were held at ancestral temples. The Liji [Classic of Rites], one of China’s classic Confucian texts on Zhou dynasty rites, written between the Warring States and early Han period, states about sacrificial offerings made to the Duke of Zhou in the great ancestral temple: “the bronze zun vessels employed were those cast in the forms of the bull victim, or an elephant, and hills; the vessel for fragrant wine was the one with gilt eyes on it”.[16] ‘Gilt eyes’ (huang mu) may well refer to a decoration as seen on the present fang hu and its companion pieces.

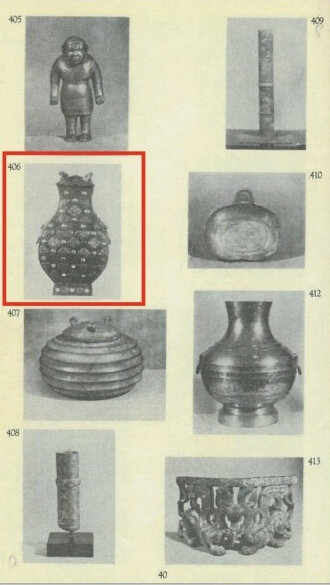

A century ago, the present fang hu was in the collection of Adolphe Stoclet (1871-1949), a Belgian industrialist, banker and famous art collector, whose villa in Brussels had been commissioned, down to the last detail, from Josef Hoffman (1870-1956), important architect and co-founder of the influential art and design cooperative, Wiener Werkstätte. It is considered the most important intact ensemble preserved from the ‘Jugendstil’ period of the early twentieth century and inscribed by UNESCO as a world heritage site. Stoclet collected Western as well as non-Western art from around the world, including many major Chinese works. The piece is visible in a photograph of a room in Stoclet’s house, taken in 1917 (fig. 10). In 1935, Stoclet lent the present bronze together with twenty-seven other Chinese works of art to the International Exhibition of Chinese Art at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, the most important exhibition of Chinese art ever mounted (fig. 11).

Fig. 10. The Fang Hu photographed in the Stoclet Palace, Brussels, 1917.© Bildarchiv Foto Marburg.

Fig 11, The fang hu illustrated in the catalogue for the International Exhibition of Chinese Art, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1935-36, cat. no. 406.

[1] Zhongguo meishu quanji. Gongyi meishu bian [Complete series on Chinese art. Arts and crafts section], vol. 10: Jin yin boli falang qi [Gold, silver, glass and enamel wares], Beijing, 1987, pls 201-204; and Shen Congwen & Li Zhitan, Boli shihua/History of Glassware, Shenyang, 2005, pls 1-7.

[2] The same photographs have been published in Seiichi Mizuno, Bronzes and Jades of Ancient China, Tokyo, 1959, col. pl. 12 and pl. 176 E; in Yūzō Sugimura, Chinese Sculpture, Bronzes and Jades in Japanese Collections, Honolulu, 1966, part 3, col. pl. 2 and pl. 40; in the exhibition catalogue Chūgoku sanzen nen: bi no bi/Select Works of Ancient Chinese Art, Mitsukoshi, Tokyo, 1973, cat. no. 16; in Li Xueqin, ed., Zhongguo meishu quanji: Gongyi meishu bian [Complete series on Chinese art: Arts and crafts section], vol. 5: Qingtong qi [Bronzes], vol. 2, Beijing, 1986, pl. 119; and elsewhere.

[3] Umehara Sueji, Rakuyō Kinson kobo shūei/Selection of Tomb Finds from Lo-yang, Chin-ts’un, Kyoto, rev. ed. 1944, pls 18 and 19.

[4] Sugimura, loc.cit.

[5] Ritual Vessels of Bronze Age China, exhibition catalogue, The Asia Society, New York, 1968, p. 154.

[6] The jar has been frequently published, for example, in Wenhua Da Geming qijian chutu wenwu [Cultural relics excavated during the Great Cultural Revolution], Beijing, 1972, p. 9; in Qian Hao, Chen Heyi & Ru Suichu, Out of China’s Earth. Archaeological Discoveries in the People’s Republic of China, New York and Beijing, 1981, pl. 191; and in Peng Qingyun, ed., Zhongguo wenwu jinghua da cidian: Qingtong juan [Encyclopaedia of masterpieces of Chinese cultural relics: Bronze volume], Shanghai, 1995, pl. 1079.

[7] Zhongguo meishu quanji, vol. 10, op.cit., pl. 201.

[8] They are discussed in Nigel Wood & Ian C. Freestone, ‘A Preliminary Examination of a Warring States Pottery Jar with So-called “Glass-Paste” Decoration, in Guo Jingkun, ed., Science and Technology of Ancient Ceramics 3: Proceedings of the International Symposium on Ancient Ceramics, Shanghai, 1995,, pp. 12-17; and in Hsieh [Xie] Mingliang, ‘Zhongguo chuqi jianyou taoqi xin ciliao [New material on early Chinese lead-glazed pottery], Gugong wenwu yuekan/The National Palace Museum Monthly of Chinese Art, no. 309, December 2008, pp. 28-37.

[9] Oriental Ceramics. The World’s Great Collections, Tokyo, New York, and San Francisco, 1980–82, vol. 10, col. pl. 65.

[10] Published in Li Xueqin, op.cit., pl. 171; and Peng Qingyun, op.cit., pl. 877.

[11] Jessica Rawson, ed., The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, London, 1992, p. 72, fig. 45.

[12] Illustrated in Jenny F. So. Eastern Zhou Ritual Bronzes from the Arthur M. Sackler Collections. New York, 1995, p. 62, fig. 110.

[13] It was included, for example, by Max Loehr in the exhibition Ritual Vessels of Bronze Age China, op.cit., cat. no. 69.

[14] So, op.cit., p. 63, fig. 112.

[15] Liang Shizheng et al., Xi Qing gu jian, 1755, vol. 20: hu, no. 22.

[16] In the translation of James Legge, Li Chi: Book of Rites, 2 vols, New York, 1967 (1885), chapter Mingtangwei; see Liu Yang, ‘To Please Those on High: Ritual and Art in Ancient China’, in Liu Yang, ed., Homage to the Ancestors: Ritual Art from the Chu Kingdom, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney, 2011, p. 34.

THE HUNDRED ANTIQUES: FINE & DECORATIVE ASIAN ART

Auction 18 – 29 September

Open for bidding online from 18 – 29 September, The Hundred Antiques: Fine & Decorative Asian Art features over 170 Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian works of art and paintings. Spanning centuries, highlights include a group of famille-noire porcelains formerly in the collection of John D. Rockefeller, Jr. and deaccessioned by a Southern institution, led by a Famille-Noire 'Bird And Flower' Pear-Shaped Vase (estimate $8/12,000); Qing dynasty glass from a California private collection, led by a Royal Blue Faceted Glass Jar and Cover (estimate $4/6,000); ‘hongmu’ furniture from the J.T. Tai & Co. Foundation, led by 'Hongmu' And Burlwood Scroll Back Armchair (estimate $3/5,000), a rare Tang dynasty gilt-bronze Buddhist figure (estimate $5/7,000), and a Qing dynasty 19th century gilt-copper stupa (estimate $1,500/2,000).

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F98%2F60%2F119589%2F129446628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F48%2F84%2F119589%2F129332637_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F70%2F65%2F119589%2F128497250_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F62%2F84%2F119589%2F128166093_o.jpg)