Sotheby's Hong Kong Chinese Works of Art Autumn Sales to feature 'Monochrome II'

Courtesy Sotheby's.

HONG KONG.- Sotheby’s Hong Kong presents two carefully curated Chinese Works of Art Sales to be held on 9 October 2020, Monochrome II and Important Chinese Art. Monochrome II is the sequel to the highly successful Monochrome sale held in July. Highlights include a jadeite-green glazed jar and cover from the Ming dynasty, a superb silver-streaked Nogime Temmoku bowl from the Southern Song dynasty and a magnificent huanghuali six-post canopy bed from the Ming dynasty. Important Chinese Art is a tightly curated assemblage with a focus on fine and rare imperial porcelain and works of art from the Ming and Qing dynasties. Highlights include an exquisite Yongzheng famille-rose 'peach' bowl and a gilt-bronze figure of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara from the Song dynasty.

Nicolas Chow, Chairman, Sotheby’s Asia, International Head and Chairman, Chinese Works of Art, comments, “This season is highlighted by the return of the Monochrome sale which showcases the timelessness of Chinese aesthetics. Sotheby’s is thrilled to offer again a superb selection of Ming huanghuali furniture which sparked exciting bidding wars in the previous season. We are also excited to present a collection of Qing monochrome porcelains from an esteemed private collection, a stunning group of Song dynasty black tea bowls from the Aoyama Studio collection, as well as an array of exquisite treasures across centuries.”

MONOCHROME II

Following on from the success of the debut Monochrome sale in July 2020, the sequel presents again a diverse range of exceptional artworks characterised by their timeless aesthetic and exemplifying the most refined sensibilities in Chinese art. The sale presents the second part of the distinguished collection of Ming furniture, a superb selection of Qing imperial monochrome porcelains from an important Asian private collection, selected archaic jades from the celebrated Hei-Chi collection, as well as a group of Song dynasty black tea bowls from the Aoyama Studio collection.

MING HUANGHUALI FURNITURE

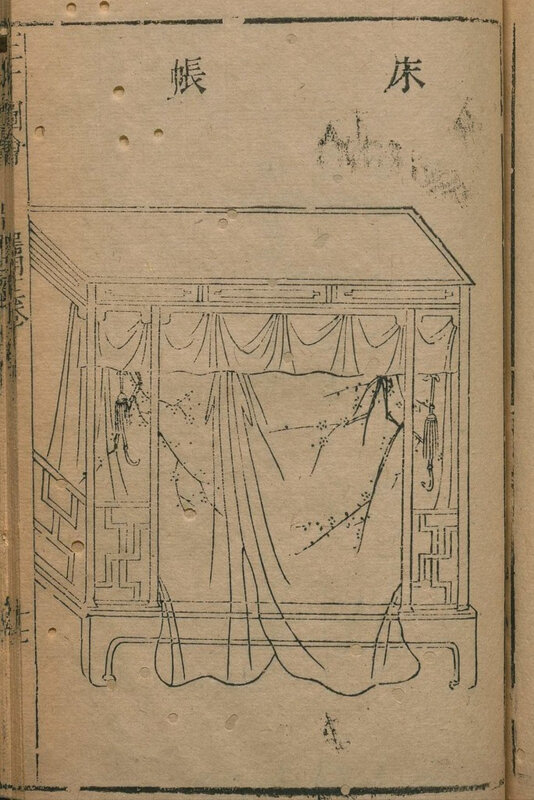

Lot 53. An Exceptional and Rare Huanghuali Six-Post Canopy Bed, Ming Dynasty, 17th Century; 226 by 156.2 by h. 226 cm. Estimate: HK$20,000,000 - 30,000,000 / US$2,580,000-3,870,000. Lot sold 23,165,000 HKD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

well proportioned, the wide rectangular frame enclosing a soft-mat sleeping surface surmounting a constricted waist carved with pairs of confronting chilong divided by short bamboo-form struts, above a shaped apron carved in low relief with stylised dragons striding amidst scrolling foliage bearing lingzhi fungus, supported on four cabriole legs with animal masks at the shoulders ending in claw-and-ball feet, the six square section posts joined with five openwork panels forming a latticework gallery, each panel comprising three horizontal sections, the two front centre sections decorated with a qilin in a landscape with its head turning backward within a cartouche, the side and back centre of conforming design with sinuous dragons alternating with stylised shou medallions, all between the top section with circular chilong roundels and the lower frieze with curling chilong, the top rail reticulated with similar chilong and shou characters, the posts joined at the top by a canopy of corresponding form.

Note: Sumptuously carved in openwork with sinuous chilong writhing around auspicious motifs, this magnificent canopy bed is a display of 17th century aristocratic splendour. Employed in the inner quarters by both men and women, beds were the focal point of the household, and six-post canopy beds were most luxurious and impressive type of bed that one could own.

This bed is discussed by the furniture scholar Wang Shixiang in Masterpieces from the Museum of Classical Chinese Furniture, 1995, p. 22, where he identifies a group of canopy beds exquisitely carved with closely related designs and suggests they were all produced at the same workshop in northern China. Two of these beds are illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum. Furniture of the Ming and Qing Dynasties (I), Hong Kong, 2002, pl. 2, the first at the Great Mosque of Xi’an, and the second in the Palace Museum, Beijing. A further closely related bed was included in the exhibition Beyond the Screen, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 2000, cat. no. 16; and two were sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 3rd December 2008, lot 2532, and 30th November 2011, lot 3075.

Illustration in sancai Tuhui [Assembled Pictures of The Three Realms], Ming dynasty, Wanli period edition.

While used by both men and women, canopy beds were the most used pieces of furniture in women’s apartments. 17th century households that adhered to Confucian norms confined women to the inner courtyards of a family compound, away from the front of the house where important male visitors were received and official functions took place. Bedrooms were informal rooms where women spent many of their waking hours, thus their furnishing, especially the bed, were important status symbols, indicating their position within the family.

During daytime, canopy beds were used as seats for informal leisure: a long table and footstool were placed in front of the bed for comfortably reading or eating. A few stools and chairs could be arranged around the bed for an informal gathering. At night, curtains were hanged within the bedframe to protect from drafts, mosquitoes as well as prying eyes. These curtains were carefully chosen as their colour and patterns emphasised the intricate openwork carving of the bedrail. The 17th century scholar Wen Zhenheng in his influential Chang wu zhi [Treaties on Superfluous Things], discusses which fabrics should be used on canopy beds: “Bed curtains for the winter months should be of pongee silk or of thick cotton with purple patterns. Curtains of paper or of plain-weave, spun-silk cloth are both vulgar, while gold brocaded silk curtains and those of bo silk are for the women’s quarters”.

Most importantly, beds were the place where children were conceived and their decoration is often filled with auspicious omens that reflect this function. On this bed sinuous chilong, young hornless dragons, dominate the design and represent the aspiration of conceiving meritorious sons. Auspicious clouds, rocks and lingzhi, and shou (longevity) characters were believed to bring blessings and good luck to those within. Designs on beds could also be indicative of a person’s social status. Wang Shixiang, op. cit., suggests that the motif on this bed of a qilin with his head turned backwards facing the sun, first found on Qing rank badges, could indicate that the bed once belonged to the wife of an early Qing official.

Six-post canopy beds are essentially a room within a room as their design aesthetic principles of Chinese classical architecture. Their six-post construction mimics three-bay buildings such as pavilions, where the roof is supported by posts and the lack of walls merges outdoor and inner space. The sophisticated openwork railings recall a building’s balustrade, which have the dual function of creating interest through their decoration and increasing stability. In addition, the upper panels under the canopy roof are carved to allow air circulation as the panels under the eaves of buildings.

The canopy bed has a long history in China, with the earliest example dating to the fourth century BC. A sophisticated wooden bed frames (chuang) was discovered at a tomb in Xinyang, Henan province, attributed to a ruler of the southern kingdom of Chu. These early beds were likely used with a canopy frame, such as the one excavated from the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) tomb of Prince Liu Sheng, in Mancheng, Hebei province. While the earliest surviving canopy bed dates to the 16th century, this type bed is often found illustrated in paintings. See for example the bed depicted in Gu Kaizhi’s (c. 344-406) handscroll Nushi zhen tu (The Admonitions of the court instructress), in the British Museum, London, accession no. 1903,0408,0.1; and the bed visible on the famous 10th century handscroll Han Xizai yeyan tu (The Night Revels of Han Xizai), attributed to Gu Hongzhong, in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in the catalogue to the exhibition Masterpieces of Chinese Paintings 700-1900, Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 2013, fig. 4.

Lot 99. An Important and Very Rare Huanghuali Table, Banzhuo, Ming Dynasty, 16th – 17th Century; 104.5 by 64.4 by h. 86.7 cm. Estimate: HK$1,200,000 - 1,800,000 / US$77,500 - 104,000. Lot sold 13,485,000 HKD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the top of standard mitre, mortise and tenon frame construction, the edge of the frame moulding downward and inward to an undulating flange simulating the edges of a lotus leaf, all above the shaped, beaded-edged apron exquisitely carved on the longer sides with a pair of phoenix soaring amidst ruyi cloud scrolls and flanking the sun, the shorter sides skilfully decorated with birds perched on floral sprigs, all resting atop four cylindrical legs terminating in baluster feet and joint to the apron and underside of the tabletop with spandrels carved in the form of sinuous dragons and ruyi-shaped braces.

Note: This exquisite table is special for its finely carved aprons and spandrels, which include a lively depiction of phoenix among clouds flanking the sun. It belongs to a highly unusual group of profusely decorated side tables, whose upper part resembles a kang table – low tables used on the heated kang. The well-known Chinese furniture scholar Wang Shixiang thus refers to them as ai zhuo zhan tui shi or 'low table with extended legs'. The abundance of carved decoration on these tables represents a clear departure from the clean and sober aesthetics more commonly associated with 17th century furniture, and demonstrates the co-existence of different furniture styles in this period.

Tables of this design are very rare and only two closely related examples appear to have been published; a table from the collection of Wang Shixiang, now in the Shanghai Museum, is illustrated in Wang Shixiang, Classic Chinese Furniture. Ming and Early Qing Dynasty, Hong Kong, 1985, pl. 84; and one included in the exhibition Beyond the Screen. Chinese Furniture of the 16th and 17th Centuries, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, 1996, cat. no. 22.

A related design is found on square tables, including one with scroll-shaped spandrels and dragons on the apron, in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in Hu Desheng, A Treasury of Ming & Qing Dynasty Palace Furniture, Beijing, 2007, vol. I, pl. 166; and a table with removable legs, from the collection of Dr S.Y. Yip, sold in these rooms, 7th October 2015, lot 118.

The graceful curves of this piece, created by its undulated waist and the shaped aprons, and its decoration are imbued with a feminine quality. The long sides of the table are carved with a motif of two phoenix facing the sun (shuangfeng chaoyang), an omen for the arrival of enlightened men, while the short sides with a pair of birds perched on flowering branches. Wang Shixiang, op.cit., p. 281, suggests that the former share similarities with designs found on contemporary brocade, while the latter with polychrome porcelains of the Wanli reign (r. 1573-1620).

EARLY MING PORCELAINS

Lot 19. An Exceptionally Rare Jadeite-Green Glazed Jar and Cover, Ming Dynasty, Yongle Period (1403-1425); 12 cm. Estimate: HK$10,000,000 - 15,000,000 / US$1,290,000-1,940,000. Lot sold 17,720,000 HKD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

finely potted with tapered sides extending to softly rounded shoulders and rising to a short straight neck, veiled in an exquisite silky jadeite-green glaze thinning at the rim and pooling around the shoulders in a sea-green tone, suffused with a fine network of craquelure resembling silver threads across the surface, the low flat cover similarly glazed.

It will be hard to find a porcelain vessel more pleasing in shape or more ravishing in colour than this small covered jar from the imperial Yongle workshops of Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province. The smooth, bulging vessel with its softly rounded cover, enveloped in a luminous, glassy, blue-green tinted glaze, has a gem-like quality as encountered only in the Yongle period (1403-1424). With its superbly designed form, its outstanding material and its perfect execution, it is a masterpiece from a golden era of China's porcelain production. No other ‘jadeite green’ jar of this shape, complete with its cover, appears to be recorded; altogether only six pieces including this jar, dressed in this dazzling glaze, appear to be extant; and only two comparable jars have retained their covers, both from the Qing court collection and today preserved in the Palace Museums in Beijing and Taipei.

The reign of the Yongle Emperor, whose rule commenced in Nanjing and ended in Beijing, was marked by extraordinary innovation in technology, imagination in design, and rigorous pursuit of quality. Specially designated imperial workshops created not only porcelain, but also lacquerware, cloisonné, textiles, Buddhist gilt-bronzes and other works of art, all of unparalleled excellence, thus initiating an unprecedented flowering of China’s arts and crafts. The imperial porcelain workshops at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province increased quantity as well as quality of their production with awesome rapidity, as the excavations of the kilns’ waste heaps have documented. As new glaze colours and firing techniques, new shapes and designs were tried out, the potters' technical leap forward was so immense, that thereafter no real innovation took place for centuries, until the introduction of foreign technology from the West in the eighteenth century supplied new impulses once more.

While many porcelains of the Yongle period were created specifically for diplomatic missions, to be distributed as imperial gifts to foreign potentates, and are characterized by larger sizes and a bolder aesthetic approach, more delicate and sophisticated wares such as this jar, were produced at the same time to cater to the needs of the imperial family and the court at large in the new palace buildings in Beijing. The present jar, which was probably designed to hold chess pieces, may have been destined for the Emperor’s private quarters towards the back of the Forbidden City. Such pieces were made with the greatest care, in very small numbers.

Many different glaze colours were experimented with at the imperial kilns during this period, and even closely related, yet clearly distinguishable shades could be created with daunting precision. No less than three types of pale greenish glazes, for example, appear to have been developed and employed side by side in the Yongle reign, all of which look rather different in real life, but less so in illustrations. In the West all three are thus generally referred to as ‘wintergreen’. In China, however, they are clearly differentiated by different terms.

The sparkling bluish-green glaze of the present jar – arguably the most desirable and the most prestigious green hue – is in China called cuiqing. Cui means ‘kingfisher’ and is used to denote any kind of blue green reminiscent of the bird’s plumage, for example, that of a kind of green bamboo, or that of jadeite. What in China is generally called ‘wintergreen’ (dongqing), but also ‘Eastern green’ (dongqing written with a different dong character), is a more typical celadon colour, more yellowish and less glassy, probably intended to imitate Longquan celadon, which is known from Yongle stem bowls. Finally, a paler, more watery, bluish-tinged glaze is seen on some deep conical bowls with incised lotus scrolls, which have been attributed to various fifteenth-century periods and in China are now generally dated to the Yongle reign. That glaze is called qingbai (‘bluish- or greenish-white’), thus again relating it to a ware of the past.

Jadeite green’, or cuiqing, porcelains are among the rarest monochrome pieces successfully created at that time. Only five other pieces glazed in this colour appear to be recorded: The pair to this jar, of the same shape, but lacking its cover, is in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing. Two closely related jars with this kind of glaze are preserved from the Qing court collection, both of very similar form, with a similar cover, but with three small lugs attached around the shoulder: one now in the Palace Museum, Beijing (fig. 1), is illustrated in Mingdai Hongwu Yongle yuyao ciqi/Imperial Porcelains from the Reigns of Hongwu and Yongle in the Ming Dynasty, Beijing, 2015, pl. 122; and again in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Monochrome Porcelain, Hong Kong, 1999, pl. 123; the other, now in the National Palace Museum, Taipei (fig. 2) was included in the Museum’s exhibition Shi yu xin: Mingdai Yongle huangdi de ciqi/Pleasingly Pure and Lustrous: Porcelains from the Yongle Reign (1403-1424) of the Ming Dynasty, Taipei, 2017, catalogue, pp. 82-3. Two other jars of this latter shape have survived without a cover: one, retaining the three lugs, is now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (fig. 3) illustrated in Wu Tung, Earth Transformed: Chinese Ceramics in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Boston, 1998, pp. 112-3 and on the dust jacket; the other, with the lugs ground down, has been sold at Christie’s New York, 16th/17th September 2010, lot 1357.

fig. 1. A Jadeite-Green Glazed Covered Jar With Lug Handles, Ming Dynasty, Yongle Period, Qing Court Collection © Palace Museum, Beijing.

fig. 2. A Jadeite-Green Glazed Covered Jar With Lug Handles, Ming Dynasty, Yongle Period. National Palace Museum, Taipei.

fig. 3. A Jadeite-Green Glazed Jar With Lug Handles, Ming Dynasty, Yongle Period, John Gardner Coolidge Collection © Museum Of Fine Arts, Boston (NO. 53.1003).

After the Yongle period this subtle colouration, which requires impeccably prepared materials and utmost control of the firing, was abandoned and never properly revived, even though a large range of exquisite bluish-green glaze tones were created again three centuries later, in the Yongzheng reign (1723-1735), quite possibly modelled on pieces such as this jar, which undoubtedly would have caught the Yongzheng Emperor’s eye.

The celadon glaze (dongqing) is known from five contemporary Yongle stem bowls: two in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in Mingdai Hongwu Yongle yuyao ciqi, op.cit., pl. 141 and The Complete Collection of Treasures, op.cit., pl. 124; and in Geng Baochang, ed., Gugong Bowuguan cang gu taoci ciliao xuancui [Selection of ancient ceramic material from the Palace Museum], Beijing, 2005, vol. 1, pl. 88; one in the Tibet Museum, illustrated in Xizang Bowuguan cang Ming Qing ciqi jingpin/Ming and Qing Dynasties Ceramics Preserved in Tibet Museum, Beijing, 2004, pl. 26; and two sold in our rooms, one with anhua dragons around the interior and a four-character Yongle mark incised in the centre, sold in Hong Kong, 24th November 1981, lot 133, and again in these rooms, 22nd March 2001, lot 90; the other unmarked, sold in our London rooms, 7th April 1981, lot 252, and in our Hong Kong rooms, 11th May 1983, lot 105. For a pale bluish-green (qingbai) glazed piece in the Palace Museum, Beijing, see the bowl from the Qing court collection illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures, op.cit., pl. 125, there also attributed to the Yongle period.

The endearing shape of this jar is also extremely rare, but is similarly seen on monochrome 'sweet-white' jars with incised decoration, now all lacking their covers; one such piece, preserved in the Shanghai Museum, is published in Lu Minghua, Shanghai Bowuguan zangpin yanjiu daxi/Studies of the Shanghai Museum Collections: A Series of Monographs. Mingdai guanyao ciqi [Ming imperial porcelain], Shanghai, 2007, pl. 4-12 (fig. 4); another was sold in these rooms, 4th June 1985, lot 1, from the J.M. Hu Family Collection; and a third jar of this form in the National Palace Museum, Taiwan, was included in the exhibition Mingdai chunian ciqi tezhan mulu/Catalogue of a Special Exhibition of Early Ming Period Porcelain, Taipei, 1982, cat. no. 55, illustrated with a non-matching cover. Like the ‘jadeite green’ jars, these white jars with incised design were also made in two similar versions, with and without lugs; for the latter see an example illustrated in Bo Gyllensvärd, Chinese Ceramics in the Carl Kempe Collection, Stockholm, 1964, pl. 664.

fig. 4. A tianbai-Glazed Jar, Ming Dynasty, Yongle Period © Shanghai Museum.

The shape may be following earlier jars for chess pieces, although the proportions and form of the cover were much adjusted in the Yongle period; for a Song (960-1279) example from the Yaozhou kilns compare the jar from the Le Cong Tang collection, sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 3rd October 2017, lot 2, illustrated together with a companion piece from the kiln site, fig. 1; for a Yuan (1279-1368) blue-and-white example see the exhibition catalogue Jingdezhen chutu Yuan Ming guanyao ciqi [Yuan and Ming imperial porcelain excavated at Jingdezhen], Yan-Huang Art Museum, Beijing, 1999, cat. no. 1.

Lot 46. A Fine and Extremely Rare Imperial Blue and Brown Glazed 'Dragon' Bowl, Ming Dynasty, Hongwu Period (1368-1398); 20.5 cm. Estimate: HK$8,000,000 - 12,000,000 / US$1,040,000-1,550,000. Lot sold 8,645,000 HKD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the interior glazed in brilliant cobalt blue and deftly decorated in anhua technique with two scaly five-clawed dragons striding amidst ruyi-shaped clouds, encircling a central ruyi-cloud medallion, the exterior subtly decorated with a band of petal lappets around the foot and covered in brown glaze.

This bowl, impressed with five-clawed dragons and glazed in cobalt blue and iron brown, appears to be unique, but it belongs to a miniscule group of bi-chrome glazed porcelains with anhua designs, among the earliest with coloured glazes. Pieces of the group are variously attributed to the late Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) or the Hongwu reign (1368-1398) of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), but a fragment of a blue-and-brown glazed vessel with anhua dragon design of this type was recovered from the site of the Ming imperial palace at Nanjing.1 It was discovered together with Hongwu blue-and-white and underglaze-red decorated porcelain fragments by the Jade Belt River (Yudaihe) that surrounded the inner palace buildings and, given this location, can be considered to represent Hongwu imperial porcelain made for use by the imperial family.

We do not know much about the Hongwu Emperor’s possible interest in the arts and crafts. Born into a very poor family and orphaned while still young, his ascent to defeat the ruling Mongols, to govern China for a solid three decades, to become the founder of one of China’s longest-lasting dynasties and, despite a total lack of prior education, to leave many writings, including a commentary on Laozi, is near-miraculous. It cannot have left him much time for aesthetic pursuits. Yet in the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province, which were founded in the Yuan dynasty, we see from the Hongwu period onwards the unquestionable emergence of an imperial style – a style that exerted a defining and lasting influence on the porcelains designed for the court right up to the end of China’s imperial era in the twentieth century. Of this, the present bowl is an archetypal example.

Many aspects of this bowls can be traced to origins in the Yuan dynasty, but in the early Ming the various features were consolidated, polished and refined and thus developed into a classic design – almost certainly evidence of strict imperial supervision of the porcelain production. Five-clawed dragons are a motif that appeared in works of art already in the Yuan dynasty, but only in the Ming was it appropriated as the foremost symbol of the person and the authority of the Emperor.

The anhua (‘hidden decoration’) technique, achieved by impressing the piece against a mould, perhaps with a thin layer of white slip in between, to create a shallow relief, was also developed in the Yuan dynasty, when it was used particularly on monochrome white pieces, but also in combination with underglaze-blue decoration as, for example, on a bowl in the Tianminlou collection, painted with a blue dragon outside and with a blue double Vajra in the centre, surrounded by white anhua dragons.2 In white on white, however, the ‘hidden’ design is often indeed difficult to make out. Under the cobalt-blue glaze of our bowl, the elegant physique and energetic stride of the dragons is strikingly evident. In the Hongwu period, the whole design became clearly defined: on bowls and stem cups it appears always with a large billowing cloud the centre, whose undulating vapours form auspicious lingzhi (longevity fungus) formations; on dishes it is combined with three smaller cloud motifs.

Both blue and brown glazes were already in use in the Yuan dynasty, but are extremely rare. Brown was hardly used at all, either for underglaze painting, or as a glaze, but a small brown-glazed inkstone box and cover from the Yuan is preserved in the Capital Museum, Beijing.3 Blue also remained very scarce, but appears on a couple of Yuan porcelains with gold decoration and on a dozen or so pieces with motifs reserved in white.4

Like with underglaze-painted porcelains, cobalt blue appears in the Hongwu period to have been used more rarely than copper red. A blue glaze can be seen on one monochrome dish with anhua dragons from the Sedgwick collection in the Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery, which was included in the Oriental Ceramic Society exhibition The Arts of the Ming Dynasty, London, 1957, cat. no. 112, and is illustrated in the accompanying Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, vol. 30, 1955-57, pl. 33. Red bowls and dishes are much more numerous, and a fragmentary bowl was found at the Hongwu stratum of the Jingdezhen kiln sites, see Chang Foundation (fig. 1).5 Others are, for example, in the Cleveland Museum of Art from the Severance and Greta Millikin collection, in the British Museum, London, from the Eumorfopoulos collection; and two from the V.W. Shriro collection were sold in our London rooms, 28th May 1963, lots 123 and 124;6 red dishes are in the British Museum, from the Sedgwick collection; in the Shanghai Museum; and in the Idemitsu Museum of Art, Tokyo.7

Fig. 1, A fragmentary red-glazed anhua 'dragon' bowl, Ming dynasty, Hongwu period, excavated from the MIng imperial kiln site at Jingdezhen. Courtesy of Jingdezhen Ceramics Archaeology Institute.

To apply two differently coloured glazes on the inside and the outside of a vessel would seem a highly complex manner of treating a vessel. It was hardly ever attempted either before or after, and only a few exceptions come to mind, such as white-and-black Ding ware bowls of the Song dynasty (960-1279), or Jiajing (1522-1566) porcelains with bicoloured glazes. Only four other pieces of the present design and glazed in this colour scheme appear to be preserved, three stem cups and one dish, and only two other bi-chrome glazed bowls of this type are recorded, but in different colour combinations:

One blue-and-brown stem cup is in the British Museum from the Sedgwick collection (fig. 2); another is in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City; and a third from the Norton collection was sold in our London rooms, 5th November 1963, lot 172.8 The three vary in size and were obviously individually fashioned rather than produced in a larger series. One blue-and-brown dish from the Eumorfopoulos collection is also in the British Museum (fig. 2).9

Fig. 2. A blue and brown glazed anhua 'dragon' dish and a stem cup, Ming dynasty, Hongwu period, © The Trustees of the British Museum (Nos 1936.1012.240 and 1968,0423.1).

A red-and-blue bowl with a cobalt-blue glaze inside and a copper-red one outside, from the collection of Lady David and later in the Idemitsu Museum of Arts, was sold in our London rooms 6th July 1976, lot 131 (fig. 3);10 and a brown-and-white bowl, glazed brown inside and probably with a neutral glaze over the white porcelain body on the outside, is in the Yamato Bunkakan, Nara.11

Fig. 3. A red and blue glazed anhua 'dragon' bowL, Ming dynasty, Hongwu period, Idemitsu Museum Of Arts, Tokyo, sold at Sotheby's London, 6th july 1976, lot 131.

Our blue-and-brown bowl with a matching stem cup and the matching dish (fig. 2) might suggest a set made for ritual use. Jessica Harrison-Hall suggests about the colouration “Conceivably it represents the blue of heaven and the red-brown of earth”.12 In this connection, it is tempting to mention, as Christine Lau has stated, that “in the tenth year of his reign (in 1377), the Hongwu Emperor decided to hold the sacrifices offered to Heaven and Earth together in one place under one roof”.13 Of course traditionally, blue was the colour of heaven and yellow the colour of earth, but bright yellow porcelain was not yet available at this period, and therefore had to be replaced with items approximating that colour, such as yellow jades, and it seems conceivable that the brown glaze might have been considered to serve the purpose. There is no indication, however, that two-coloured wares were ever used for such combined rituals, nor that wares of this type were made for ritual purposes at all, although the existence of stem cups might suggest this.

1 See Zhu Ming yicui. Nanjing Ming gugong chutu taoci/A Legacy of the Ming. Ceramic Finds from the Site of the Ming Palace in Nanjing, Art Museum, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 1996, no. 26.

2 Lin Yeqiang (Peter Y.K. Lam), ‘Yuan qinghua longwen kao: Yi Zhizheng ping wei zhongxin/Dragons on Yuan Blue-and-White as Seen from the Bands on the David Vases’, Li Zhongmou et al., Youlan shencai. 2012 Shanghai Yuan qinghua guoji xueshu yantaohui lunwenji/Splendors in Smalt. Art of Yuan Blue-and-white Porcelain Proceedings, Shanghai, 2015, vol. 2, pp. 194-205, fig. 23.

3 Zhongguo taoci quanji [Complete series on Chinese ceramics], Shanghai, 1999-2000, vol. 11, pl. 249.

4 Zhongguo taoci quanji, op.cit., pls 241-244.

5 Imperial Hongwu and Yongle Porcelain Excavated at Jingdezhen, Chang Foundation, Taipei, 1996, cat. no. 15.

6 Sherman E. Lee and Wai-kam Ho, Chinese Art under the Mongols. The Yüan Dynasty (1279-1368), The Cleveland Museum of Art, Cleveland, 1968, cat. no. 165; Jessica Harrison-Hall, Catalogue of Late Yuan and Ming Ceramics in the British Museum, London, 2001, no. 2:3.

7 Harrison-Hall, op.cit., no. 2:4; Lu Minghua, Shanghai Bowuguan zangpin yanjiu daxi/Studies of the Shanghai Museum Collections: A Series of Monographs. Mingdai guanyao ciqi [Ming imperial porcelain], Shanghai, 2007, pl. 3-8; Idemitsu Bijutsukan: Kaikan jūgo shūnen kinen ten zuroku/The Fifteenth Anniversary Catalogue, Tokyo, 1981, col. pl. 766.

8 Harrison-Hall, op.cit., no. 1:20; Chinese Art under the Mongols, op.cit., cat. no. 160.

9 Harrison-Hall, op.cit., no. 1: 21.

10 It is also illustrated in Chinese Art under the Mongols, op.cit., cat. no. 162; and in Idemitsu Bijutsukan, op.cit., col. pl. 765.

11 Yamato Bunkakan shozōhin zuhan mokuroku 7. Chūgoku tōji/Chinese Ceramics from the Museum Yamato Bunkakan Collection, Illustrated Catalogue Series No. 7, Nara, 1977, no. 114.

12 Harrison-Hall, op.cit., p. 69.

13 Christine Lau, ‘Ceremonial Monochrome Wares of the Ming Dynasty’, in Rosemary E. Scott, ed., The Porcelains of Jingdezhen, Colloquies on Art and Archaeology in Asia, no. 16, London, 1993, p. 94.

SONG DYNASTY BLACK TEA BOWLS FROM THE AOYAMA STUDIO COLLECTION

Property from the Aoyama Studio Collection. Lot 31. An Exceptional and Rare Heirloom 'Jian' Silver-Streaked 'Nogime Temmoku' Teabowl, Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279); 12 cm. Estimate: HK$12,000,000 - 16,000,000 / US$1,550,000-2,070,000. Lot sold 9,855,000 HKD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

superbly potted, the deep rounded sides rising from a short straight foot to a rim indented with a thin concave groove, unctuously covered with a lustrous black glaze with iridescent silvery-blue ‘hare’s fur’ streaks, the glaze draining from the rim and falling short of the foot in a glossy black bulge revealing the dark brown body, the rim bound with metal, Japanese wood box.

The love and connoisseurship of black-glazed tea bowls from Fujian is intimately connected with the homage paid to these ceramics by Japanese collectors and tea masters. In Japan, ‘Jian’ ware tea bowls were revered virtually from the moment they left the kilns in the Song dynasty (960-1279), and the Japanese term temmoku (or tenmoku) is now universally accepted for this group of black-glazed bowls, as lasting testimony of this reverence.

Black tea bowls were particularly appreciated in Buddhist monasteries, where tea was drunk for its beneficial effects on body and mind as well as ritually offered to the Buddha. The seemingly humble aspect of black tea bowls made them particularly appropriate in this context. The groove below the rim made them comfortable to hold, their heavy potting had an insulating effect, keeping the tea inside hot while protecting the fingers outside from the heat, and their dark interiors made for a striking contrast with the white froth of whipped tea.

In Japan, where whipped tea continues to be ritually prepared and consumed in the Tea Ceremony, black ‘Jian’ tea bowls became associated with monasteries in the Tianmu (Japanese: temmoku) mountain range in Lin’an county, north Zhejiang province, now a nature reserve renowned for its giant ancient Japanese cedar trees, visited also by the Qianlong Emperor (r. 1736-95) and still famous for its Tianmu tea. Temmoku tea bowls were probably brought to Japan together with Fujian tea by Buddhist monks visiting Chinese monasteries in the Song dynasty. They are still worshipped in Japan today, several of them having gained the rank of National Treasures.

The Jianyang kilns of Fujian, which produced nothing but tea bowls, annually supplied them as tribute to the court and the Huizong Emperor (r. 1101-1125), one of China’s greatest imperial art lovers, patrons and tea connoisseurs, is known to have been fond of them.

‘Jian’ ware became known in the West through the efforts of James Marshall Plumer (1899-1960), an American who in the 1930s worked at the Fuzhou Office of the Chinese Maritime Customs and fell in love with the black tea bowls offered in the city’s antique shops. Determined to locate the kilns, he set out in 1935 on a perilous journey to this remote and at that time dangerous rural area in inner Fujian, first travelling in his own car, which he had to abandon at the fourth river crossing, then by ferry boat, carrying on by rail, rickshaw, bus, bamboo raft, mail boat and on foot, bribing highwaymen to secure safe passage, but often stopped by floods that had carried away parts of the road or a bridge. He was the first to locate the kilns in the region of Shuiji and through his teaching and a posthumously published survey made the ware widely known, well beyond the circles of tea lovers in China and Japan (James Marshall Plumer, Temmoku: A Study of the Ware of Chien, Tokyo, 1972).

The striking black glazes can show various different effects, when air bubbles in the glaze burst, leaving a pattern of streaks, compared to hare’s fur (Japanese nogime), or spots compared to oil spots (Japanese yuteki), that can range in tone from rust brown to metallic blue. While pieces with rust-brown ‘hare’s fur’ streaks are the best known and most characteristic ‘Jian’ ware tea bowls, those with bluish ‘oil spots’ are the rarest and most celebrated. In between, there exists an endless variety of different glaze effects, for which no specific names have been coined, which determine the relative desirability of ‘Jian’ tea bowls. With its sparkling glaze interspersed with metallic silvery to coppery steaks, the present bowl is among the rarest and most highly coveted nogime examples.

A wide range of different temmoku bowls is published in Tōbutsu temmoku [Import commodity ‘temmoku’], Chadō Shiryōkan, Kyoto, 1994, including some of the finest examples preserved in Japan as well as bowls excavated in Fujian province. Among the former, most closely reminiscent of the present bowl, also with metallic shimmering, copper-coloured streaks, are bowls from the Kyoto National Museum and the Tokugawa Art Museum, pp.19ff, pls 10, 13, 15, 16. This effect of the iron-brown specks taking on this metallic sheen is so rare that it is hardly encountered among the many wasters found at the kiln site, and only a few comparable fragments are illustrated ibid., pp. 64ff., pls 47 bottom right, 48 and 61, and p. 103, reference pl. E.

The characteristic feature of ‘Jian’ tea bowls of the glaze inside having pooled off-centre, which has been remarked by many scholars, has been discussed in an article by Marshall P.S. Wu, who suggests that a deliberately oblique setting of the bowls in the saggar helped to avoid the formation of stalactiform glaze drops that might stick to the saggar (Marshall P.S. Wu, ‘Black-glazed Jian Ware and Tea Drinking in the Song Dynasty’, Orientations, vol. 29, no. 4, April 1998, pp. 22ff, figs 2-5)

Lot 2. A Superb and Rare Cizhou Russet-Splashed Black-Glazed 'Partridge Feather' Bowl, Northern Song Dynasty (960-1127); 13 cm. Estimate: HK$800,000 - 1,200,000 / US$104,000-155,000. Lot sold 1,512,000 HKD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

potted with a deep and subtly rounded body rising from a short foot to a flared rim, the interior covered with a glossy black glaze liberally and densely splashed with short russet 'partridge feather' mottles, the exterior covered in a persimmon glaze stopping neatly above the footring to reveal the pale buff stoneware body.

Note: This bowl is remarkable for its captivating pattern of irregular russet splashes on the interior, which creates a striking contrast to the lustrous dark brown glaze. Known as zhegu ban, or ‘partridge feathers’, this pattern evolved from the experimental nature of Song dynasty kilns as they competed in producing wares for the thriving tea market. Bowls covered in a lustrous dark-brown glaze heightened the aesthetic experience of drinking tea, which at the time was energetically whisked to produce a rich white froth. The present bowl is a particularly fine example of its type, as it features small and evenly applied flecks, suggesting it was made in the Northern Song period. Stonewares coated in rich dark glazes began to be produced in large numbers in the Tang period (618-907), with the finest examples made at kilns near the Yellow River. The monochromatic glazes soon led the way to painted or splashed designs, which were achieved by either splashing or applying with a brush an iron-oxide slip over the glaze. In the kiln, the gravity would pull the slip downwards creating irregular splashes or streaks. Not only were these wares particularly suitable for drinking whisked tea, the serendipitous nature of their glaze must have captivated the imagination of Song literati.

The mesmerising ‘partridge-feather’ glaze was produced at many kilns in both northern and southern China, attesting to its popularity. Most examples were made at kilns that produced Cizhou wares, such as the Guantai kilns in Hebei province, the Qinlongsi and Dangyangyu kilns in Henan province. Bowls of similar form, recovered at Guantai, Ci county, are illustrated in The Cizhou Kiln Site at Guantai, Beijing, 1997, col. pl. 29, figs 1 and 3, pl. 65, fig. 1; and a larger bowl from Dangyangyu, the glaze similarly covering also the interior of the foot, is published in Series of China’s Ancient Porcelain Kiln Sites. Dangyangyu Kiln of China, Beijing, 2011, pl. 56.

Two bowls of similar proportions, from the Sheinman collection, now in the Arthur M. Sackler Museum, Harvard University Art Museums, were included in the exhibition Hare’s Fur, Tortoiseshell and Partridge Feathers. Chinese Brown- and Black-Glazes Ceramics, 400-1400, Harvard University Art Museums, Cambridge, cat. no. 38a and b; a bowl formerly in the collection of Lord Cunliffe, was included in Principal Wares of the Song Period from a Private Collection, Eskenazi, London, 2015, cat. no. 23; and a further similar bowl from the collection of Frederick M. Mayer, was sold at Christie's London, 24th June 1974, lot 55.

ARCHAIC JADES FROM THE HEI-CHI COLLECTION

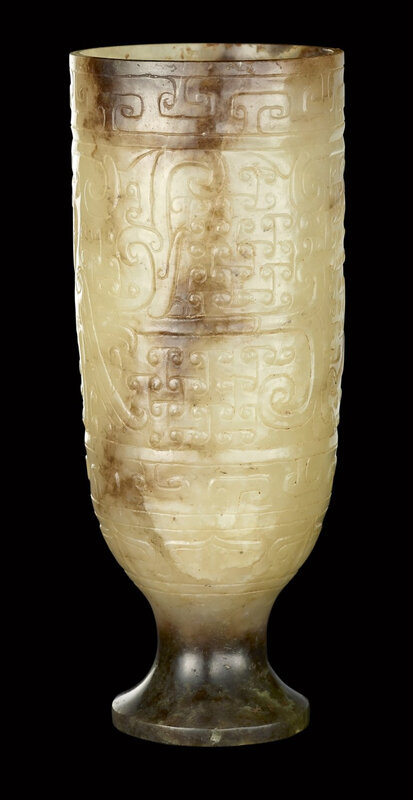

Lot 16. An Extremely Rare and Important Jade 'Twin Bird' Stem Cup, Western Han Dynasty (206 BC – AD 9); 11.3 cm. Estimate: HK$6,000,000 - 8,000,000 / US$775,000-1,040,000. Lot sold 21,955,000 HKD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the cylindrical vessel tapering to a short waisted stem and splayed circular foot, the exterior skilfully worked with a pair of phoenix-like birds striding forward, each mythical bird portrayed crested and with a long tail, the body accentuated with scrollwork echoing the interlinked 'C'-scrolls on the ground of the frieze and the bands of T-shaped motifs, all above a border of stylised petal motifs above the foot.

Provenance: Acquired in Hong Kong, 20th June 1993.

Exhibited: Ancient Chinese Jade, J.J. Lally & Co., New York, 2018, cat. no. 130.

Around the time of the Western Han (206 BC – AD 9), jade stem cups of this type were items of the highest prestige produced for the Chinese imperial house, local royalty and a privileged elite connected to these courts. Related beakers have been discovered at some of the period’s most important residential and burial sites, and were in tombs placed in prominent position. They were not ordinary wine cups, but are believed to have been used in connection with immortality rites, possibly as receptacles to contain gathered dew which, mixed with powdered jade, is said to have been consumed as immortality elixir. The bird decoration on the present cup appears to be unique, but would seem to support such usage.

A cup from the tomb of Zhao Mo, King of Nan Yue (r. 137-122 BC), at Xianggangshan, Guangdong province, formed part of an elaborate construct that not only secured it against toppling but also emphasized its significance: It was placed on a pedestal in the centre of a large bronze tripod basin, with a trefoil jade disc around it, like a collar, and with three silver dragons with golden heads rising from the basin to hold the disc; see James C.S. Lin, ed., The Search for Immortality. Tomb Treasures of Han China, The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, 2012, cat. no. 164, pp. 58 and 287-9.

The present cup is remarkable for its superbly designed and executed, majestic bird motif. The phoenix-like bird with its down-curved beak, up-curved crest, fanciful tail, standing on one leg, clearly represents the Vermillion Bird (zhuque) of the South, which is associated with the element fire and with the force of yang. The cosmological concept of yin and yang and the five elements, associated with the directions (plus the centre), was one of the foundations of Daoist immortality rites. The Red Bird therefore occupies a prominent position in Han iconography and is ubiquitous in Han art, depicted in many different media, in jade, for example, carved in openwork on a pendent, also from the royal tomb of Zhao Mo, see Su Bai, ed., Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo zhongda kaogu faxian/Great Archaeological Discoveries of the People’s Republic of China. 1949-1999, Beijing, 1999, p. 274 (fig. 1); in gilt-bronze in form of finials, e.g. on the famous jade wine container in the Harvard Art Museums (Lin, op.cit., p. 169, fig. 54); and in many Han stone reliefs, e.g. one from Suining county, Jiangsu (Käte Finsterbusch, Verzeichnis und Motivindex der Han-Darstellungen [Register and index of motives in Han illustrations], Wiesbaden, 1966-2004, vol. 1, no. 553)(fig. 2).

fig. 1. An openwork pendant with the Red Bird, Western Han dynasty, excavated from the mausoleum of King of Nanyue, Guangzhou, Guangdong, Museum of The Western Han Mausoleum of King of Nanyue.

fig. 2. A rubbing of a Han stone relief from Suining County, Jiangsu. After: Käte Finsterbusch, Verzeichnis und Motivindex der Han-Darstellungen [Register and Index of Motives in Han Illustrations], Wiesbaden, 1966-2004, Vol. 1, No. 553.

The design here used as a backdrop, which looks like a fairly regular geometric pattern, is in fact a most sophisticated design of whorls turned in different directions, joined up in pairs both horizontally and vertically but in an irregular manner, thus imbuing the formal ornament with life. On the present piece, the pattern helps to focus attention on the birds as it serves to texture the ground. Companion pieces are mostly decorated with whorl patterns only, and sometimes have a baluster-shaped stem.

Somewhat earlier in date is a beaker recovered from the site of the Epang palace outside Xi’an, Shaanxi province, which had been commissioned by Emperor Qin Shihuang (r. 221-210 BC) (p. 45, fig. 142); see The First Emperor. China’s Terracotta Army, The British Museum, London, 2007, cat. no. 92; another cup, closely related in shape and with the whorl pattern enclosed between related scroll borders, was excavated from a tomb at Luobowan, Guixian, Guangxi province, apparently belonging to a high official of the Nan Yue Kingdom and dating from the long reign of the first Nan Yue King, Zhao Tuo (r. 203-137), see Guangxi Guixian Luobowan Han mu/Luobowan Han Dynasty Tombs in Guixian County, Beijing, 1988, col. pl. 8 and pl. 28, fig. 3 (fig. 3); and a forth cup from a royal tomb of the Zhu kingdom at Shizishan, Xuzhou, Jiangsu, is published in Zhonghua Renmin Gongheguo zhongda kaogu faxian, op.cit., p. 260; compare also a beaker of this type from the Sze Yuen Tang collection, sold at Bonhams Hong Kong, 5th April 2016, lot 38 for a world record price, together with a related cup missing its stem, lot 42.

fig. 3. A jade stem cup, Western Han Dynasty, excavated from a tomb at Luobowan, Guixian, Guangxi Province, Museum of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. After: Zhongguo Meishu Quanji: Gongyi Meishu Bian [Complete Series On Chinese Art: Arts And Crafts Section], Vol. 9: Yuqi [Jades], Beijing, 1991, Pl. 177.

This beaker shape, made elegant through its waisted stem, came into use already prior to the Han dynasty and survived it, but not for long. Prototypes may have been pieces of lacquer, at the time also a highly prestigious material, see The First Emperor, op.cit., p. 102, but the royal tomb of Zhao Mo also contained a similar bronze stem cup and cover inlaid with jade plaques (Lin, op.cit., p. 66, fig. 39).

Although no other bird-decorated cup appears to have survived from the Han period, such designs seem to have inspired the later production of archaistic vessels, such as a cylindrical tripod cup with handle from the collection of Quincy Chuang, attributed to the late Ming (1368-1644), where the bird is depicted with a complex, emphatically angled curlicue of tail feathers against a diaper design made up of squared scroll motifs; see the Asia Society exhibition Chinese Jades from Han to Ch’ing, Asia House Gallery, New York, 1980, cat. no. 140.

Lot 21. A Rare and Large Calcified Yellow Jade Zhulong ('Pig Dragon') Neolithic Period, Hongshan Culture (c. 3800-2700 BC); 10 cm. Estimate: HK$2,000,000 - 3,000,000 HKD / US$258,000-387,000. Lot sold 2,520,000 HKD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

of generous proportions, the iconic coiled body further accentuated with a superbly rendered wrinkled snout, the signature slit below the sealed lips terminated before meeting the central perforation, the neck drilled for suspension.

Literature: Jiang Tao and Liu Yunhui, Jades from the Hei-Chi Collection, Beijing, 2006, p. 27.

Note: Notable for its large size, this carving depicts a zhulong, or pig-dragon, a modern term that describes the animal’s upturned snout, prominent bulging eyes and coiled body. Considered to represent the prototype of depictions of mythological dragons in later Chinese art, zhulong are some of the most interesting creations of the enigmatic Hongshan culture (c. 3500 BC), and evidence the existence of a complex system of belief in supernatural forces.

Jade zhulong have been recovered at various tomb sites in Northern China, often placed on the chest of the tomb occupants, suggesting they were worn as chest ornaments. These carvings have been studied by Elizabeth Childs-Johnson in ‘Jades of the Hongshan Culture’, Arts Asiatiques, vol. XLVI, December 1991, pp. 82-95, where she identifies the territory of the Liaoxi and Liaodong peninsulas, and the upper and lower valleys of the Liao river as the areas where these Hongshan remains originated from. While the function of these carvings have not been determined, fragments of a zhulong have been recovered at a fertility temple complex in Niuheliang, Kezuo, Liaoning province, suggesting a connection with fertility rituals.

A jade zhulong of similar proportions is illustrated in Roger Keverne, Jade, London, 1995, p. 62, fig. 22; a slightly larger one in the Liaoning Provincial Institute of Archaeology and Cultural Relics is illustrated in Hongshan wenhua yuqi jianshang [Connoisseurship of jades from the Hongshan culture], Beijing, 2014, p. 94, no. 1; and another in the Tianjin Museum, is published in Tianjin shi yishu bowuguan cang. Yu [Jades in the Tianjin Museum], Hong Kong, 1993, pl. 7. See also a slightly smaller yellow jade zhulong recently sold in these rooms, 11th July 2020, lot 102 [https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2020/monochrome-hk0939/lot.102.html].

QING IMPERIAL PORCELAINS

Lot 10. An Extremely Rare Celadon-Glazed Ewer, Seal Mark and Period of Yongzheng (1723-1735); 25 cm. Estimate: HK$2,000,000 - 3,000,000 / US$258,000 - 387,000. Lot sold 3,276,000 HKD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

after a metalwork form, exquisitely potted with a straight body encircled by an incised formal foliate scroll with fine feathery leaves between raised scalloped borders, the shoulder with a raised incised floral scroll surmounted by a tall neck with a rounded bulb in the centre rising to a flared rim opening into a spout, the bulb with small floral sprigs with upright leaves above and pendent petal panels and pearl strings below, covered overall with an elegant pale celadon glaze.

Provenance: Sotheby's Hong Kong, 31st October 1995, lot 408.

Note: The unusual form of this attractive and rare ewer appears to be derived from a Middle Eastern metal shape, but such foreign vessels were rarely taken directly as models in the Qing dynasty. It was generally the potters of the Yongle period in the early Ming dynasty who copied such forms, and the present ewer form, which exists both with and without handle, and comes also with blue-and-white decoration in early Ming style, may be an adaptation of an early Ming porcelain form, which in turn is based on Middle Eastern metal prototypes. Compare a fragmentary white porcelain ewer recovered from the Yongle stratum of the Ming imperial kiln sites, included in the exhibition Imperial Porcelain of the Yongle and Xuande Periods Excavated from the Site of the Ming Imperial Factory at Jingdezhen, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1989, cat. no. 6. However, a 12th/13th century Iranian metal ewer from the Keir collection, which is more closely related to this Qing dynasty form than to the early Ming version, is illustrated in Geza Fehervari, Islamic Metalwork of the Eighth to the Fifteenth Century in the Keir Collection, London, 1976, pl. 15.

A very similar ewer of this rare celadon-glazed type from the Avery Brundage collection is in the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, illustrated in He Li, Chinese Ceramics. A New Standard Guide, London, 1996, pl. 544; see also one sold at Christie’s London, 28th/29th June 1965, lot 98, from the Richard C. Fuller collection; and another sold at Christie's Hong Kong, 28th November 2005, lot 1312, from the Ruth P. Phillips collection.

Vessels of this form are also known with other monochrome glazes, such as a white ewer from the Grandidier collection in the Musée Guimet, Paris, illustrated in Oriental Ceramics. The World's Great Collections, Tokyo, New York, San Francisco, 1980-82, vol. 7, fig. 170. Compare another white ewer from the collection of Edward T. Chow, illustrated by Regina Krahl, Chinese Ceramics in the Meiyintang Collection, London, 1994-2010. Vol. 2, no. 794, and sold in these rooms, 8th April 2013, lot 3050.

Lot 22. A Fine and Rare Guan-Type Quadruple Vase, Seal Mark and Period of Yongzheng (1723-1735); 10.2 cm. Estimate: HK$1,500,000 - 2,000,000 / US$194,000-258,000. Lot sold 1,890,000 HKD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

masterfully potted as four conjoined vases of slender cylindrical form with a short neck and everted rim, covered overall in an unctuous pale bluish-grey glaze suffused with a matrix of yellowish-brown crackles, the footring applied with dark brown dressing, each base with one character of the four-character seal mark in underglaze blue.

Note: Inspired by Song dynasty prototypes, conjoined vases of this charming and unusual form were an innovation of the Yongzheng reign, and required craftsmen’s utmost attention in potting and firing. A slightly smaller vase of this type in the Palace Museum, Beijing, is illustrated in Qingdai yuyao ciqi [Qing imperial porcelains], vol. 1, Beijing, 2005, pl. 149; two were sold in these rooms, the first, 24th May 1985, lot 503, the second, 22nd May 1984, lot 185, and again, 8th April 2011, lot 3002; and one from the collection of Stephen Junkunc III, sold in our New York rooms, 20th March 2019, lot 518.

Vases of this form with Yongzheng marks and of the period, are also known covered in other monochrome glazes: see an example with a Ru-type glaze, in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, included in the museum’s exhibition Qing Monochrome Porcelain, Taipei, 1981, cat. no. 77; a celadon-glazed example from the J.M. Hu Collection, sold in our New York rooms, 4th June 1985, lot 40; and a slightly smaller version covered in a teadust glaze, also sold in our New York rooms, 21st March 2018, lot 536.

IMPORTANT CHINESE ART. AN EXTREMELY FINE AND RARE FAMILLE-ROSE 'PEACH' BOWL

Property from the Alan Chuang Collection. Lot 3622. An Extremely Fine and Rare Famille-Rose 'Peach' Bowl, Mark and Period of Yongzheng (1723-1735); 14.3 cm. Estimate: HK$25,000,000 - 35,000,000 / US$3,200,000 - 4,500,000. Lot sold 26,795,000 HKD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

superbly enamelled in vivid tones of rose-pink, shades of green, yellow, iron-red, brown and black with two varieties of flowering and fruiting peach branches issuing from the foot and extending across the exterior and over the rim onto the interior, one branch with a brownish-black bark and bearing white double blossoms, the other with a brown bark and bearing five-petalled rose-pink blossoms, both with large ripe fruit delicately coloured in shaded tones of yellowish-green to subtle raspberry-pink, depicted in iron red with two bats on the exterior and three on the interior forming the wufu, the base inscribed in underglaze blue with a six-character reign mark within a double circle.

Note: Yongzheng porcelain bowls with famille-rose peach-and-bat design are extremely rare. The present bowl, with five peaches all rendered on the exterior, appears to be unique, as other examples are designed with six peaches, four on the exterior and two on the interior. Another unusual feature of the present piece is that the fruits do not have the heavy pink outlines seen on other examples, which demonstrates the superb skills of the porcelain painters and the marvellous possibilities of the new famille-rose palette.

Five is a propitious number, and the five red bats painted on the bowl are among the most popular themes in Chinese decorative arts. Red bats provide a rebus or visual pun for vast good fortune, and five bats provide a rebus for wufu, the Five Blessings of longevity, health, wealth, love of virtue and a good end to life. Bats painted upside down provide a further rebus, since the word for ‘upside down’, dao, is pronounced similarly to the word for ‘arriving’, and thus an upside-down bat signifies 'happiness is arriving'.

Five is a propitious number, and the five red bats painted on the bowl are among the most popular themes in Chinese decorative arts. Red bats provide a rebus or visual pun for vast good fortune, and five bats provide a rebus for wufu, the Five Blessings of longevity, health, wealth, love of virtue and a good end to life. Bats painted upside down provide a further rebus, since the word for ‘upside down’, dao, is pronounced similarly to the word for ‘arriving’, and thus an upside-down bat signifies 'happiness is arriving'.

Two court paintings further demonstrate the popularity of the bat motif at the Yongzheng court: a landscape by Chen Mei (c.1694-1745) with a large number of bats in the sky, inscribed Ten Thousand Blessings (bats) to the Emperor and presented to the Yongzheng Emperor on his birthday in the 4th year of his reign (1726) (fig. 1), ibid., cat. no. 270; and another, by court artist Jin Jie (fl. 18th century), depicting three elderly men in a landscape with red bats, titled Flying Bats Filling the Sky (i.e. Infinite Blessings), in Harmony and Integrity, op.cit., cat. no. II-112 (fig. 2).

fig. 1. Chen Mei (C.1694-1745), Ten Thousand Blessings (Bats To The Emperor, Presented to the Yongzheng Emperor on his birthday in 1726, Ink and colour on silk. © Palace Museum, Beijing

fig. 2. Jin Jie, Longevity As High As The Mountains, The 5th Leaf, Qing Dynasty, 18th Century, National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Only a dozen comparable Yongzheng bowls of the peach-and-bat design are recorded. A pair was formerly in the collection of T.T. Tsui, published in The Tsui Museum of Art. Chinese Ceramics IV: Qing Dynasty, Hong Kong, 1995, pl. 155, and The Tsui Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1991, pl. 119. The pair, now separated, was composed of a bowl that was sold in these rooms 14th November 1989, lot 315; at Christie's Hong Kong, 26th April 1999, lot 539; in our London rooms, 16th May 2007, lot 104; and in these rooms, 7th April 2015, lot 112, together with another similar bowl. The other bowl of the Tsui pair came from the John F. Woodthorpe and C.M. Moncrieff collections and was sold three times in our London rooms, 9th December 1952, lot 140; 6th April 1954, lot 106; and 21st February 1961, lot 171.

A pair formerly in the Eisei Bunko, Tokyo, an art collection with its origins in the Nanboku-cho period (1336-92) formed by the Hosokawa family, one of the top daimyo clans in Japan, is now also separated: one bowl entered the Meiyintang collection and was sold in these rooms on 5th October 2011, lot 16, the other, still in the Eisei Bunko today, is illustrated in Sekai tōji zenshū/Ceramic Art of the World, vol. 12, Tokyo, 1956, col. pl. 11. Another pair in the Baur collection, Geneva, is illustrated in John Ayers, The Baur Collection Geneva: Chinese Ceramics, Geneva, 1968-74, vol. 4, nos A 594 and 595. A pair from the collections of Chen Rentao, Paul and Helen Bernat and T. Endo was sold in these rooms 15th November 1988, lot 44, and 29th April 1997, lot 401, and at Christie's Hong Kong, 29th May 2007, lot 1374, and is illustrated in Sotheby's. Thirty Years in Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2003, pl. 326. This pair is now also separated and one was included in the Fiftieth Anniversary Exhibition: Twelve Chinese Masterworks, Eskenazi, London, 2010, cat. no. 11, while the other is in a private collection in Taiwan. Another pair was sold at Yamanaka & Co., London, 1938, and was included in their catalogue Chinese Ceramic Art, Bronze, Jade etc., no. 116, pl. 12 (illustrating one of the pair). Also known is one bowl from the Avery Brundage collection, in the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, published in Terese Tse Bartholomew, Hidden Meanings in Chinese Art, Asian Art Museum, San Francisco, 2006, p. 204, pl. 7.44.1.

One other related pair of different proportions, from the Allen J. Mercher and John M. Crawford, Jr. collections, was sold at Parke-Bernet New York, 10th October 1957, lot 261, and in these rooms, 24th May 1978, lot 252. The peach-and-bat design was also used for enamelling porcelains at the imperial workshops in the Forbidden City in Beijing. Compare a pair of Yongzheng falangcai porcelain bowls in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, also painted with peach trees and five bats, but in a less pronounced design, exhibited in Painted Enamels of Qing Yongzheng Period (1723-1735), National Palace Museum, Taipei, 2013, pl. 82.

Other Yongzheng vessel forms with the peach-and-bat design are also very rare. Compare a Yongzheng covered box formerly in the Van Slyke and Meiyintang collections, sold in these rooms 8th April 2013, lot 3036, which appears to be the only example recorded (fig. 3). Examples of large dishes include one from the collection of J. Pierpont Morgan, sold in these rooms, 29th April 1997, lot 400, and one in the Palace Museum, Beijing, in China. The Three Emperors 1662-1795, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 2005-6, cat. no. 181. A group of smaller dishes is discussed in An Exhibition of Important Chinese Ceramics from the Robert Chang Collection, London, 1993, cat. no. 92; see also an example in the British Museum, London, illustrated in Oriental Ceramics, The World's Great Collections, vol. 5, New York, 1981, col. pl. 67; and another dish in Denise Patry Leidy, Treasures of Asian Art. The Asia Society’s Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller 3rd Collection, New York, 1994, pl. 198. Other examples include a pair of Yongzheng dishes formerly in the collections of Barbara Hutton (1912-1979) and the British Rail Pension Fund, exhibited on loan at the Dallas Museum of Art, 1985-1988, illustrated in Sotheby's Hong Kong Twenty Years, Hong Kong, 1993, p. 202, no. 276, and sold twice in our London rooms, 6th July 1971, lot 265, and 8th July 1974, lot 408, twice in our Hong Kong rooms, 29th November 1977, lot 160, and 16th May 1989, lot 88, and recently at Christie’s Hong Kong, 28th May 2014, lot 3319.

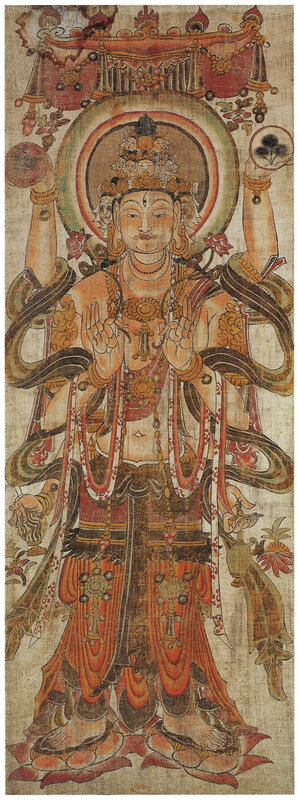

AN EXTREMELY RARE AND IMPORTANT MASSIVE GILT-BRONZE FIGURE OF BODHISATTVA AVALOKITESHVARA

Lot 3619. An Extremely Rare and Important Massive Gilt-Bronze Figure of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, Song Dynasty (960-1279); 61 cm. Estimate: HK$20,000,000 - 30,000,000 / US$2,600,000 - 3,900,000. Courtesy Sotheby's.

well cast and portrayed seated in vajraparyankasana, the right hand lowered in varada mudra, while the left held in abhaya mudra, each hand marked with a half-shuttered eye, the serene face bearing a compassionate expression with eyes in a downward gaze, the forehead marked with a third eye, his slightly pursed lips framed by a scrolling mustache and beard, the hair neatly drawn up in an intricate jatamakuta securing three miniature effigies of bodhisattvas, with long tresses falling to the shoulders, wearing elaborate jewellery including hair ornaments with billowing sashes and dragon heads, circular studded earrings, beaded necklaces, armbands, bracelets and anklets, a shawl detailed with lotus scrolls around the bare shoulders flowing over the arms, a voluminous lower garment similarly incised with a couple of dragons interspersed within the design, and gathered at the waist and fastened by a beaded girdle.

This gilt-bronze Avalokiteshvara figure is highly idiosyncratic in style and outstandingly rare, with only one other comparable sculpture being recorded, in the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, from the Avery Brundage collection. While its modelling and casting quality is beyond any doubt, it is not easy to immediately place it in the history of Chinese Buddhist bronze sculpting.

Buddhist gilt bronze figures were produced in China almost right from the start, when Buddhism was embraced by various courts in the period of China’s division after the Han dynasty (206 BC – AD 220). Until the Tang dynasty (607-906), however, they remained very small. A first development away from small votive images took place already in the Khitan Liao dynasty (907-1125), when sculptures not only became bigger, but also underwent a stylistic treatment towards a more abstract sculptural beauty. Yet it was to take another important step before precious gilt-bronze images such as the present figure, in a size comparable to the much cheaper wooden sculptures, were commissioned. This development culminated in the Yongle period (1403-24), when the court took total control of their production – as it did for other artefacts, in particular porcelain and lacquer – and a distinct style was devised, which should become classic and determining for all future design of Buddhist gilt-bronze images.

It would seem that the sculptors of the present figure had not yet seen a Yongle image and were thus innocent enough to formulate their own style. Between Tang and Ming (1368-1644) dynasties, a multitude of imperial and royal courts – the Five Dynasties (907-60), Liao, Song (960-1279), Jurchen Jin (1115-1234), Tangut Western Xia (1038-1227) and Mongol Yuan (1279-1368) – exerted influence on the appearance of works of art, both religious and secular, so that not one style gained overall acceptance. The stylistic variety of works of art in that period can therefore be overwhelming, and the artistic development is by no means one-directional.

The present sculpture is therefore something like a phare in an uncharted sea. It comes from a period when the Guanyin image had not yet turned sweet and feminine, and although the basic facial features suggest a woman’s face, the addition of small curls to indicate beard and moustache are an unmistakeable effort to counterbalance this effect. This way of representing Avalokiteshvara is characteristic of Tang painting executed at Dunhuang in Gansu province, either in form of wall paintings inside the Caves or banners and other textiles discovered there.

Models for the style of a figure such as this could have been sketches as were done for wall paintings, some of which have survived. An ink sketch of a Bodhisattva head, drawn on the reverse of an earlier Daoist manuscript that was used as scrap paper, has been discovered at Dunhuang and is now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris. It shows a very similar head with moustache and beard, sharply curved eyebrows, thick lips, neck with horizontal folds, and rich jewellery and ribbons; it was included in the exhibition Chine: L’empire du trait. Calligraphies et dessins du Ve au XIXe siècle, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris, 2004, cat. no. 36a, where it has been tentatively attributed by Nathalie Monnet to the late Tang or Five Dynasties, 10th century (fig. 1).

fig. 1. Ink Sketch of A Bodhisattva Head, Detail, Late Tang to Five Dynasties, 10th Century, Discovered at Dunhuang, Gansu © Bibliothèque Nationale de France

This sketch is echoed in a large number of Buddhist paintings from Dunhuang, done over an extended period from the late Tang through the Five Dynasties to the early Northern Song (960-1127) dynasty, which can be attributed to the 9th and 10th centuries. Compare, for example, paintings of Guanyin figures illustrated in Jacques Giès, Les arts de l’Asie central. La collection Paul Pelliot du musée national des arts asiatiques – Guimet, Paris, 1996, vol. I, pls 52-72, and vol. II, pls 11-35.

A group of paintings attributable to the 10th century, the Five Dynasties to early Northern Song, shows an even closer Bodhisattva image with multiple heads similar to the present figure, often with an eye on the forehead and hands, also richly adorned with jewellery and often with similar facial features; see in particular Giès, op.cit., vol. I, pls 86, 89-93, and vol. II, pls 64 and 65 (figs 2 and 3).

fig. 2. Avalokiteshvara with thousand arms and thousand eyes, detail, Northern Song dynasty, 10th century © Musée Guimet, Paris, Dist (NO. EO 1173). RMN-Grand Palais / Droits réservés

fig. 3. Standing Avalokiteshvara With Eleven Heads, Five Dynasties To Northern Song Dynasty © Musée Guimet, Paris, Dist (NO. EO 3582). RMN-Grand Palais / Droits réservés

There is also a standing wooden Bodhisattva figure carved in a related style in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, possibly also from the Dunhuang Cave complex in Gansu, attributed to the 10th/11th century (with a radiocarbon date range of 970-1120), illustrated in Denise Patry Leidy and Lawrence Becker, Wisdom Embodied. Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2010, cat. no. A38.

Stylistically, facial features and proportions of this sculpture are also reminiscent of Guanyin images carved into the rock at the Huayan Caves, Anyue county, Sichuan province, which can be attributed to the Northern Song dynasty; see Zhongguo meishu quanji: Diaosu bian [Complete series on Chinese art: Sculpture section], 12: Sichuan shiku diaosu [Sichuan cave sculpture], Beijing, 1988, pls 128 and 130.

The closely related gilt-bronze Avalokiteshvara figure in the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco, which is lacking the rich ornaments and ribbons around the head, is illustrated in René-Yvon Lefebvre d’Argencé, ed., Chinese, Korean and Japanese Sculpture in the Avery Brundage Collection, San Francisco, 1974, pl. 159 (fig. 4).

fig. 4. Gilt-Bronze Seated Figure of a Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara with Four Heads, Song Dynasty, The Avery Brundage Collection, B60s543 © Asian Art Museum, San Francisco. Used By Permission.

While Yuan dynasty qingbai figures of similar size may at first glance seem closely related, they tend to be much softer and more distinctly feminine in appearance; see four Guanyin figures, from the collections of C.P. Lin, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, and the Metropolitan Museum, New York, illustrated in Stacey Pierson, ed., Qingbai Ware: Chinese Porcelain of the Song and Yuan Dynasties, London, 2002, pls 119-22.

It is highly unusual to find a Bodhisattva figure wearing a dragon-decorated robe, but the dragons seen on the present gilt bronze also confirm a pre-Yuan attribution. Compare similar seemingly boneless incised dragons with the head almost dissolved into a cloud motif and three-clawed feet with nails not yet set off at an angle, on Song dynasty Ding wares, for example, a dish and a washer included in the exhibition Qianxi nian Songdai wenwu dazhan/China at the Inception of the Second Millennium: Art and Culture of the Sung Dynasty, 960-1279, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 2000, cat. nos II-21 and III-17 (fig. 5).

fig. 5. Dingyao dish with incised dragon, detail, Northern Song dynasty, 11th century, National Palace Museum, Taipei

ADDITIONAL HIGHLIGHTS

Lot 3608. An Outstanding Blue and White Moonflask, Ming Dynasty, Yongle Period (1403-1425); 29.5 cm. Estimate: HK$15,000,000 - 20,000,000 / US$ 1,940,000 - 2,590,000. Courtesy Sotheby's.

modelled after a Middle Eastern metal prototype, elegantly potted with a flattened spherical body with two domed sections, each side centred with a yin-yang medallion radiating an eight-pointed starburst, the foliate points interspersed between palmette or ornaments, all within a formal 'half-cash' diaper border around the edge, surmounted by a waisted neck and a small bulb-shaped mouth, collared by a foliate scroll band of aster and carnation, flanked by a pair of gracefully arched handles with terminals similarly adorned with floral sprays, all raised on a low oval foot, the cobalt blue of a brilliant tone with characteristic 'heaping and piling', Japanese wood box.

Provenance: Kochukyo Co. Ltd., Tokyo, 1980s.

Note: This flask represents one of the archetypal wares created at the imperial kilns in Jingdezhen during the early Ming dynasty, a design that appears to have been equally popular with the Chinese rulers as with foreign royalty. It belongs to a group of vessels which derived their inspiration from Persian prototypes and represented a new stylistic avenue for Chinese porcelain. The angular bulb and short oval foot are characteristic of Yongle flasks of this large size. Closely related examples include one in the collection of the Ottoman sultans in Turkey, illustrated in Regina Krahl, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, Istanbul, London, 1986, vol. 2, pl. 616; one from the Qing court collection, preserved in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, and included in the Museum’s exhibition Pleasingly Pure and Lustrous. Porcelains from the Yongle Reign (1403-1424) of the Ming Dynasty, 2017, pp. 140-141 (fig. 1); one from the Shanghai Museum, Shanghai, included in the exhibition Seika jiki ten [Exhibition of blue and white porcelain], Matsuya Ginza, Tokyo, 1988, cat. no. 16; and another, from the Jingguantang and Huang Ding Xuan collections, included in the exhibition In Pursuit of Antiquities. Thirty-Fifth Anniversary Exhibition of the Min Chiu Society, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1995, cat. no. 124, sold in these rooms, 29th October 1991, lot 29, and twice at Christie's Hong Kong, 3rd November 1996, lot 545, and again, 28th November 2006, lot 1512. Another example was sold in our Paris rooms, 18th December 2009, lot 65.

fig. 1. A blue and white moonflask, Ming dynasty, Yongle period, Qing Court Collection, National Palace Museum, Taipei.

The same design is also found adorning one side of flasks of similar form, but of slightly smaller size and with larger rounded bulbs, the other side decorated with a related design of interlaced petals and ruyi motifs; for example see one exhibited in the Shihua Art Museum, Shanghai, 2010, and published in Zhao Yueting, ed., Huangdi de ciqi. Jingdezhen chutu 'Ming san dai' guanyao ciqi zhenpin huicui [Porcelains of the emperors. Compilation of imperial porcelain treasures of 'The Three Ming Reigns' excavated at Jingdezhen], Shanghai, 2010, pl. 23, together with a plain white flask without a foot attributed to the early Yongle period, pl. 19, and a blue-and-white Xuande-marked example with a rectangular foot, pl. 68. See also a Xuande mark and period flask from the Qing court collection in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, exhibited in Pleasingly Pure and Lustrous, op.cit., pp. 142-143 (fig. 2), together with two white-glazed examples of this form, one undecorated and the other incised with interlaced petals, pp. 136-139. The subtle evolution of the form and design over the decades can be traced in these flasks.

fig. 2. A blue and white moonflask, Ming dynasty, Mark and period of Xuande (1426-1435), Qing Court Collection, National Palace Museum, Taipei.

The design and shape of this flask appear to have derived from Near or Middle Eastern pottery or metal prototypes, although no exact counterpart has yet been found. Its possible origin is discussed in Margaret Medley, 'Islam and Chinese Porcelain in the 14th and Early 15th Centuries', Bulletin of the Oriental Ceramic Society of Hong Kong, no. 6, 1982-4, where a Xuande-marked flask in the Sir David Percival collection is illustrated, fig. 11; and in John Alexander Pope, 'An Early Ming Porcelain in Muslim Style', Aus der Welt der Islamischen Kunst. Festschrift für Ernst Kuhnel, Berlin, 1959, where another blue-and-white flask is published, pl. 3B, together with a large inlaid brass canteen with similar strap handles and 'garlic' mouth, pl. 1B, the latter from the Eumorfopoulos Collection, sold in our London rooms, 5th June 1940, lot 72, and now in the Freer Gallery of Art, Washington D.C., no. F1941.10.

The star-shaped rosettes adorning either side of the flask are composed in a highly stylised and geometric manner. Both its formality and abstraction are unusual in a Chinese context and, together with the enclosing chevron and geometric border, are probably also the result of Middle Eastern inspiration. However, the traditional Chinese design repertoire is represented through the flower-scroll band at the neck and the small floral sprigs at the handles, although the combination of asters and carnations is rare. The delicacy of the floral elements also serves to soften the rigidity of the overall design. Flasks of this model were popular during and peculiar to the Yongle and Xuande periods.

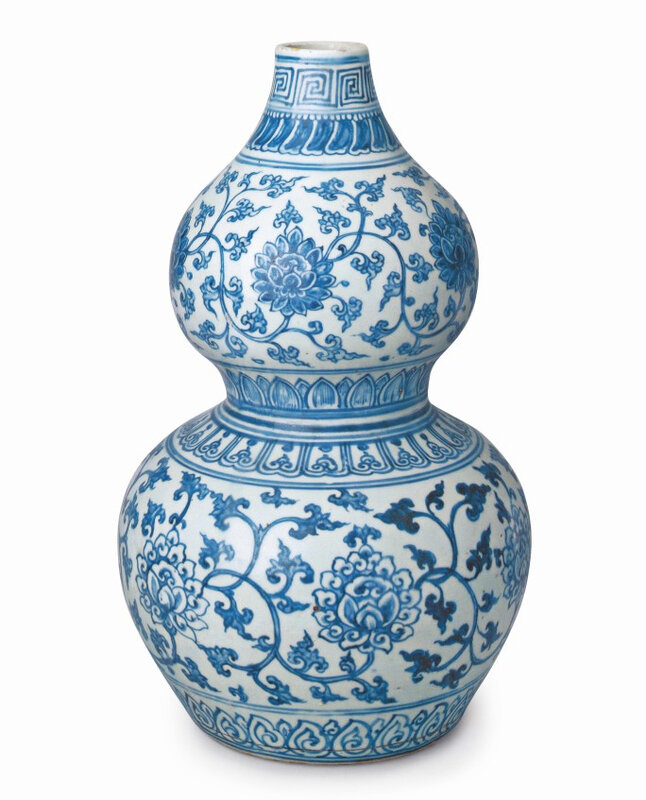

Lot 3609. An Extremely Rare and Superb Blue and White 'Lotus Scroll' Vase, Yuhuchunping, Ming Dynasty, Chenghua Period (1465-1487); 30.3 cm. Estimate: HK$12,000,000 - 18,000,000 / US$1,560,000-2,330,000. Courtesy Sotheby's.

beautifully potted with a pear-shaped body rising from a splayed foot, elegantly sweeping up to a waisted neck flaring at the rim, the exterior boldly painted with large lotus blooms borne on a leafy meander above overlapping petal lappets, below upright plantain leaves, an undulating lingzhi scroll and pendent trefoils encircling the neck, all divided by line borders repeated at the rim and the foot, covered overall in an unctuous glaze with a faint bluish tinge.

Towards a Distinctive Style: A Superb Chenghua Vase

Blue and white wares of the Chenghua period are extremely rare. Even rarer are those of such exceptional quality, upright form and large size. Chenghua porcelain in general displays a very distinct character both in terms of material and style of decoration. Initially heavily influenced by the attractive style of the Xuande reign, the Chenghua potters gradually developed their own distinctive sophisticated style by making a deliberate move away from earlier models, perhaps most evident in the idiosyncratic forms and designs they developed. The present vase is a fine and unique example of such transformation; while its motifs and form are rooted in traditions established from the beginnings of the Ming dynasty, they are presented in an unusual yet strikingly elegant manner. Veiled with a lustrous silky glaze, this vase can be identified as a mid-Chenghua period creation. ‘Softer’ to the touch than its predecessors, it marks a departure from the crisp and glossy glazes of the finest Xuande wares and towards the muted, velvety glaze of the famous Chenghua palace bowls.