An extremely rare and important porcelain cup with golden silver mounting, the Chinese cup, Jiajing period (1522-1566)

Lot 172. An extremely rare and important porcelain cup with golden silver mounting, the Chinese cup, Jiajing period (1522-1566), the mounting probably English around 1580-1585; 13.3 x 9.3 cm. Estimate: 200,000.00-300,000.00 EUR. Courtesy Bertolami Fine Art.

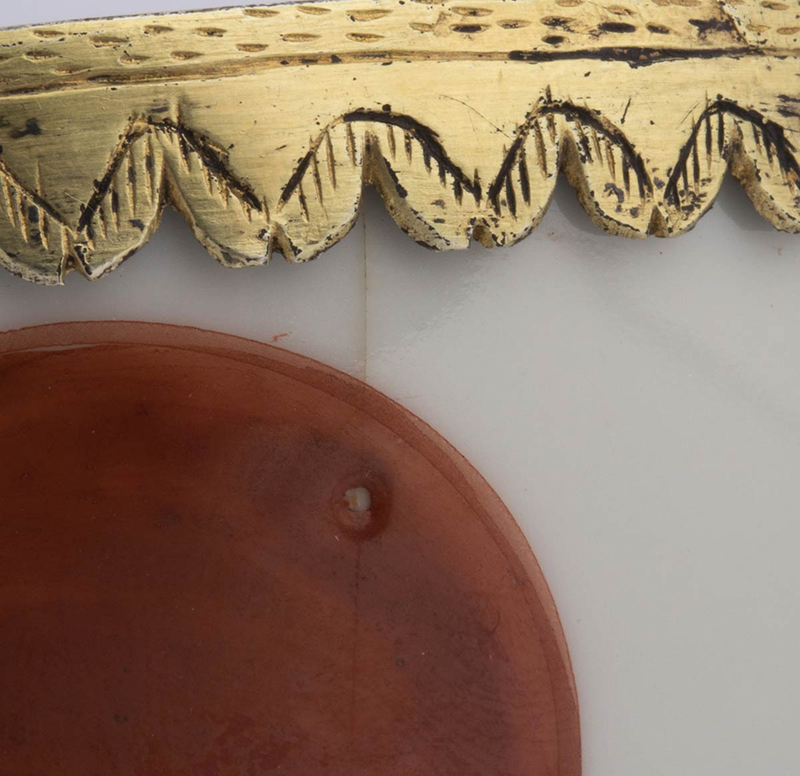

Decorated on the outside with four large circular medallions in red on the white of the glazed body, the porcelain cup is supported by a slender stem that rises from a rounded circular foot and is secured by four vertical bands worked 'in the day', the hem emphasized by a notched band, the entire frame enriched with engraved and chiseled details, the foot with masks alternating with fruits, the median section of the stem with three lion masks with a mobile ring between the jaws and three shells, the four vertical bands with mascaron ends.

Provenance: by tradition, Elisa Baciocchi (1777-1820), Grand Duchess of Tuscany and sister of Napoleon Bonaparte; purchased by Francesco Lugrammi, a high official of the Kingdom of Italy, and by him to his son Giulio Lugrammi (1876-1958), Commander General of the Port of Marseille and senator of the Kingdom of Italy who participated in the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 , then to his son (1906-1991) and finally to his grandson.

Note: Its main importance, however, probably lies in the story it tells. A very long history, lasting more than four centuries. A story that involved high personalities who lived on at least two continents, Asia and Europe. From the Chinese emperor Jiajing (reign 1522-1566), during whose reign it was executed, to probably Elizabeth Queen of England (1533-1588), by Elisa Baciocchi Grand Duchess of Tuscany and sister of Napoleon, to the Lugrammi family, who preserved proudly this piece for about two centuries.

Along with these very influential names in world history, it also tells of a pivotal moment in the fascinating story of the encounter between two very distant cultures, China and Europe.

Since the 14th century, porcelain has certainly been the most precious material that could arrive in Europe from China. From the time of Marco Polo onwards, Chinese pottery has become the most desired commodity by all European princes. Before direct trade between Asia and the Portuguese began towards the beginning of the 16th century, the number of Chinese porcelain reaching Europe was small. Even if they could not understand the real composition of that material, the most influential members of the European elite understood the extraordinary qualities of Chinese porcelain, its thin and white body, its impermeability and the vividness of its painted or molded decoration, completely unlike anything they had seen until then.

Chinese porcelain was simply precious, and it was worthy of being enriched with mounts, often made by the best artists specializing in metalworking. The rarity of Chinese porcelain and the preciousness of the frames were qualities that combined to create objects of extreme refinement that could be exhibited in the most important Chambers of Wonders (Wunderkammern), those rooms where European princes kept their most precious treasures.

Much of the still existing Chinese porcelain arrived in the 14th and 15th centuries has a metal frame, or was originally provided with one, such as the famous so-called "Gaignières-Fonthill" vase (Dublin, National Museum), donated in 1381 by Louis I of Hungary to Charles III King of Naples (A. Lane,The Gaignières-Fonthill Vase. A Chinese Porcelain of about 1300 , in “The Burlington Magazine”, CIII, 1961, 697, pp. 124, -132, pl. 2-11), or the céladon glazed bowl now in the Hessisches Landesmuseum in Kassel, purchased by Count Philipp von Katzenelnbogen around 1433-34 and certainly mounted before 1453 ( Porzellan aus China und Japan. Die Porzellagalerie der Langgrafen von Hessen-Kassel , Kassel 1990, pp. 10-11, 216-218).

The use of enriching Chinese porcelain with metal frames continued into the following centuries, although the increase in porcelain imported from China grew dramatically with the advent of the various European East India Companies in the 16th-17th centuries, reaching a peak in the 18th century France. The style of these frames obviously adapted to changes in taste.

The gilded silver frame that enriches this cup shows stylistic characteristics that immediately recall the canons of the late Renaissance and Mannerism, due to the presence of decorative motifs such as grotesques connected by lion masks, shells and bacchanal masks.

A taste that can be related to the period of the reign of Elizabeth, Queen of England and Ireland from 1558 to 1603. It is known for documentary evidence that the queen received as gifts in the 1880s a certain number of mounted cups. in porcelain (A. Jefferies Collins, ed., Jewels and Plate of Queen Elizabeth I, London 1955, p. 592, n. 1582), and among this the cup now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York ((inv.n.68.141.125a / b, gift of Irwin Untermyer, 1968), whose setting is presumably the work of one of his favorite goldsmiths, Affabel Partridge. The setting of the cup in the Metropolitan Museum cannot be compared to the setting of the piece discussed here, as the latter is more complex in its general conception and clearly richer in its decorative details. However, its stylistic features are typical. of artists active in Europe towards the end of the 16th century, including in England at the court of Queen Elizabeth, and there are some possibilities that it too is a work of the aforementioned Affabel Partridge.

The oldest and most well-known Chinese porcelain mounted in England is the "Lennard Cup", so-called because it was owned by Samuel Lennard (1553-1618), lord of a manor at Wickham Court, West Wickham (British Museum, Percival David Collection: see S . Pierson, Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art. A Guide to the Collection , London 2003, p. 71, no. 58). The porcelain is from the Jiajing period, the beautiful setting has a London hallmark that dates it around 1560-1570. From a stylistic point of view, despite many differences, this cup shares roughly the same chronology with the one discussed here.

Again with regard to the setting, the comparison with the two "Von Manderscheidt Cups", one sold in London by Sotheby's (5 February 1970, lots 169, 170), the other in the collections of the Victoria & Albert Museum (R . Kerr, Chinese Porcelain in Early European Collections , in Encounters. The Meeting of Asia and Europe 1500-1800, exhibition catalog edited by A. Jackson and A. Jaffer, London 2004, pp. 44-51: p. 48, pl. 4.4). An inscription on one of the two cups records that the two pieces were mounted in 1583 in memory of Count Hermann von Manderscheidt at the behest of his brother Count Eberhart who most likely bought them a year earlier traveling to Jerusalem, perhaps in Turkey. These two porcelain bowls are also from the Jiajing period like the one discussed here, but the style of their decoration cannot be compared, although there are similarities in the type of setting, decorated with groups of fruit and masks.

The analysis of diplomatic relations between England and the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Queen Elizabeth is also significant in the context in which we have entered. The two countries in fact signed a treaty in 1580 with which they established better commercial ties, thanks to the activity of William Harborne (-1618) who had been appointed ambassador in 1586. At that time the Turkish sultans had already amassed a large quantity of porcelain. Chinese, the basis of the extraordinary collection now in the Topkapi Saray Museum in Istanbul. The presence of a cup very similar to the one discussed here in that collection (R. Krahl, Chinese Ceramics in the Topkapi Saray Museum, 2 volls, London 1986: II, p. 824, n. 1658) could be an indication of the provenance of our porcelain bowl, although at the moment there is no documentary evidence that can confirm this.

The cup of the Topkapi Saray Museum is dated to the Jiajing period, although it has no mark. Its main decorative feature is the presence of the red circular medallions on the outside of the wall. This motif is typical of a group of bowls produced in Jingdezhen in the mid-sixteenth century, very popular in Japan where it takes the name of akadama (literally "red spot decoration"). In some cases, bowls of this type have an additional gold decoration, which is the reason why they are known by the Japanese definition of kinrande. Kinrande-style bowls were also among those Chinese porcelain from the Jiajing period that reached Europe in the mid-16th century, such as the two specimens from Ambras Castle (W. Seipel,Exotica. Portugals Entdeckungen im Spiegel fürsstlicher Kunst- und Wunderkammern der Renaissance , exhibition catalog, Vienna 2000, no. 209).

Bertolami Fine Art. Live Auction, starts 18 October 2020 from 11:00 CEST (lots 1-202) and from 15:00 CEST (lots 203-470).

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240325%2Fob_7bcfdc_telechargement.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F66%2F24%2F119589%2F129574942_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F51%2F84%2F119589%2F129412544_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F23%2F73%2F119589%2F129071666_o.jpg)