HONG KONG - Christie’s Hong Kong Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art auctions will take place on 30 November with four dedicated themed auctions — Imperial Glories From The Springfield Museums Collection, The Chang Wei-Hwa Collection of Archaic Jades, Inspiring The Mind — Life Of A Scholar – Official, and Important Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art.

Chi Fan Tsang, Deputy Chairman, Specialist Head of Department, commented, “We are privileged to be presenting some of the finest works through the course of Chinese history, showcasing the ever-evolving aesthetics of celebrated Chinese art forms across time. The curated sales this season cater to the diverse tastes of our clients who seek works of exceptional quality and rarity.”

Continuing the tradition of offering renowned institutional collections at auction, Christie’s is privileged to be presenting a dedicated sale of Chinese works of art from the Springfield Museums, the largest cultural institution in western Massachusetts: Imperial Glories From The Springfield Museums Collection. Leading this sale is A Magnificent And Exceptionally Rare Large White Jade Carving Of Shoulao And Deer (Estimate: HK$5,000,000 – 7,000,000).

Property from the Springfield Museums Collection. Lot 2908. A Magnificent And Exceptionally Rare Large White Jade Carving Of 'Shoulao And Deer’, Qianlong-Jiaqing period (1736-1820); 10 11/16 in. (27.2 cm.) high. Estimate: HKD 5,000,000 - HKD 7,000,000 (USD 648,058 - USD 907,281). © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

The boulder is superbly carved depicting Shoulao, the Star God of Longevity, holding a peach in one hand, the other hand holding a staff in the form of a gnarled branch tied with a scroll and flanked by a small bat in flight, accompanied by his deer. The white stone is of an even tone with an attractive, soft polish.

Provenance: George Walter Vincent Smith (1832-1923), Springfield, Massachusetts, acquired prior to 1910.

The current figure on exhibit at the George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, circa 1896 to 1910

Note: This figure is exceptionally well-carved with details meticulously rendered, particularly evident on the thread-like, silky beard and graceful folds of the robe. Very few carved figures from the Qing dynasty are of such substantial size, and the jade boulder is extraordinarily even in tone, well-polished with a soft sheen. While Shoulao represents the Star God of Longevity in the Daoist Pantheon, the deer accompanying him in this carving is a homophone for lu, ‘wealth’; and the bat hovering above is a homophone for fu, ‘happiness’. Together, the imagery represents Longevity, Wealth and Happiness.

A slightly smaller white jade carving of a Luohan (23.7 cm.), similarly carved with a voluminous robe with multiple folds, is in the Qing Court Collection and now in the Palace Museum (fig. 1), illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, Jadeware (III), Hong Kong, 1995, no. 108. Compare also a smaller white jade carving (15.5 cm.) depicting the Star God of Longevity and Star God of Happiness together, also from the same collection, illustrated ibid., no. 106.

fig. 1. A white jade carving of a Luohan, Qing dynasty, 23.7 cm, Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing.

Continuing the tradition of offering renowned institutional collections at auction, Christie’s is privileged to be presenting a dedicated sale of Chinese works of art from the Springfield Museums, the largest cultural institution in western Massachusetts: Imperial Glories From The Springfield Museums Collection. Leading this sale is A Magnificent And Exceptionally Rare Large White Jade Carving Of Shoulao And Deer (Estimate: HK$5,000,000 – 7,000,000).

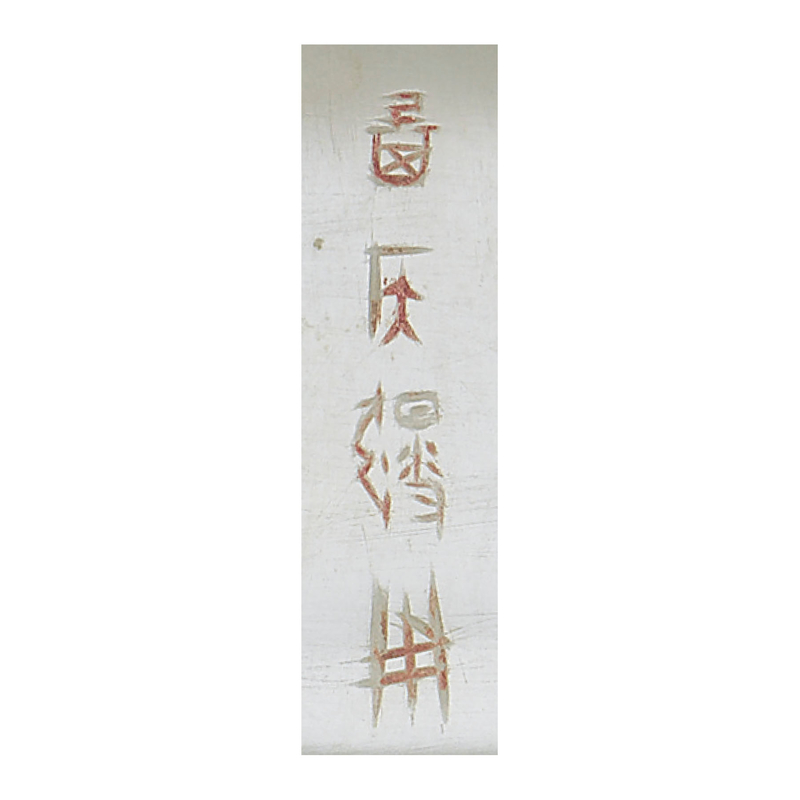

Lot 2707. A Highly Important Inscribed ‘Marquis Mi’ White Jade Ge-Halberd Blade, Late Shang Dynasty, C. 1300-1100 BC, 11 1/2 in. (29.8 cm.) long. Estimate HKD 2,500,000 - HKD 4,000,000(USD 324,029 - USD 518,446). © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

The blade is carved with a median ridge extending on both sides with bevelled edges continuing to where the blade begins to taper to the point, with a hole drilled through the tang below incised cross-hatching design between horizontal lines. A four-character inscription in oracle-bone script, Qi hou Mi yong, ‘for the use of the Marquis Mi of Qi ’, is incised in a vertical line next to the hafting bar. The jade has a superb even creamy-white tone with an unctuous texture.

Provenance: Jinhuatang Collection, acquired in Taipei in 1998.

The white jade blade is dated to late Shang period, and is 29.5 cm. long with a 20.5 cm. shaft; the handle is 7.5 cm. wide and 9 cm. long. It is opaque white in colour with some light brown inclusions. The blade tapers to a sharp triangle with a downward tip, and has a spine and twin knife edges. It has a straight handle with an L-shaped profile at the end. There is a circular aperture at the top of the handle between the guard, and incised decoration on the handle consisting of a band of lozenges flanked by double lines. There is a vertical four-character inscription Qi hou Mi yong(㠱侯彌用)in oracle bone script near the top edge before the guard. The inscription and the decoration are carved with sharp and unlaboured lines. It is polished overall with sophisticated craftsmanship, and made for ceremonial purposes.

This dagger-axe, ge, is closely related to the Shang Dynasty jade dagger-axe (fig. 1) inscribed with the characters Zuo Ce Wu, excavated in Yelin Village in Qingyang county, Gansu province, and now in the Gansu Qingyang Municipal Museum (fig. 1); it is also comparable to several jade dagger-axes excavated in 1976 from the tomb of Fuhao in Henan province.

fig. 1. Line drawing of a Shang jade dagger-axe, ge inscribed with the characters Zuo Ce Wu, now in the Gansu Qingyang Municipal Museum.

It is extremely rare to find archaic jades from the late Shang, Western and Eastern Zhou periods bearing inscriptions. Notable examples include those excavated in the Guo Kingdom tombs, such as the jade ge inscribed with four characters xiao chen Xi, the jade cong with the characters xiao chen Tuo jian and the jade cylindrical bead with wang Bai, all from the tomb of Guo Zhong excavated in 1990; the jade pendant inscribed wang Bai from the tomb of Meng Ji excavated in the same year; and another jade ge inscribed with three characters xiao chen from the tomb of Madame Guo Ji excavated in 1991. There is also the jade ge inscribed with the characters Bi gong zuo yu excavated in 1996 from the Warring States tomb in Tanggonglu, Luoyang, Henan Province. In the Tianjin Municipal Art Museum there are the Shang Dynasty jade fragment carved with cyclical-date characters, and the jade staff finial inscribed with Xing qi ming (‘Maxim on the Circulation of Qi’ with 45 characters) previously in the collection of Republic collector Li Mugong (1877-1950). In the Freer Gallery in Washington there is the jade ge inscribed with the characters tai bao, dated to the Early Western Zhou period and once in the collection of late Qing collector Duan Fang (1861-1911). Each of these pieces is an important example in the fields of Chinese philology and history.

The current white jade ge inscribed Qi hou Mi yong (For the use of Marquis Mi of Qi) appears to be the only jade known to bear the character Qi, while Mi is possibly the name of the Marquis of Qi. The character Qi appears on Shang oracle bones, such as the one inscribed with lao Qihou (old Marquis of Qi) (Heji , 36416); as well as the one recording military activities of the Qi state (Jia, 2398 and 5877) - evidence that Qi was the name of a vassal state since the Shang period.

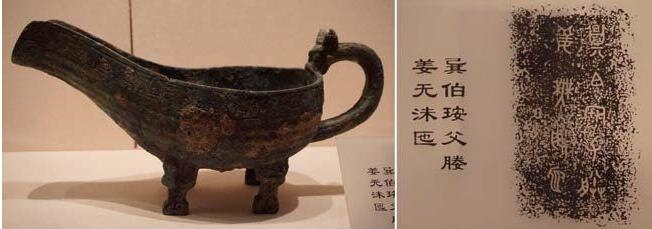

Amongst archaic bronze vessels dated to the Shang and Zhou periods, those bearing the name Qi were excavated in a wide variety of locations, including Shandong, Hebei, Henan, Shaanxi and Liaoning. Some scholars postulate that perhaps the Qi armies regularly accompanied the Shang and Zhou Kings on their military campaigns. Furthermore, the inscription on the ‘Wangfu’ yi vessel (fig. 2), now in the Shanghai Museum, indicates that Lady Mengjiang of Qi was married to the King, showing the close alliance of the two houses. Several other excavated vessels bearing this clan name attest to the wide ranging influence of the Qi state in the Shang and Zhou periods, including the ‘Qi Bozi An Fu Zheng’ xu vessels (fig. 3), ‘Qi Bo An Fu’ yi vessel (fig. 4), ’Qi Bo An Fu’ pan vessel (fig. 5), all excavated in Nanfucun in Shandong, 1951; ‘Qi Hou’ ding vessel (fig. 6) excavated in Shangkuangcun in Shandong, 1969; the ‘Pei’ fangding vessel excavated in Beidongcun in Liaoning, 1973; the ‘Qi Mu’ ding vessel excavated in Qizhen in Shaanxi, 1973.

fig. 2. Rubbing of the inscription on the ‘Wangfu’ yi vessel, now in the Shanghai Museum.

fig. 3. The ‘Qi Bozi An Fu Zheng’ xu vessels, rubbing of the inscription and transcription.

fig. 4. The ‘Qi Bo An Fu’ yi vessel, rubbing of inscription and transcription.

fig. 5. The ’Qi Bo An Fu’ pan vessel, rubbing of inscription and transcription.

fig. 6. The ‘Qi Hou’ ding vessel, rubbing of inscription.

Even though there are many oracle bone and bronze examples of this clan name, Qi did not appear in ancient textual references until the Eastern Han period, when historian Wei Hong wrote in Gu Wenguan shu: Qi (㠱)is the name of an ancient state, synonymous with Qi (杞). Although he did not provide any textual evidence for this claim, it was taken as true by successive scholars such as Ding Du (990-1053) when he was chief editor of official dictionaries, Xue Shanggong (?-?) in the Southern Song period, and Xu Han (1797-1866) and Chen Jieqi (1813-1884) of the mid-Qing period.

However, linguist and philologist Duan Yucai (1735-1815) in the Qianlong/Jiaqing period had a different theory: ‘According to Jiyun, Qi is the name of an ancient state. Wei Hong claimed that it is synonymous to Qi (杞). This is because Wei Hong claims Qi is the Qi of Qi Song (杞宋),however this claim is from a Tang source citing spuriously Wei Hong’s Guwen Guanshu, and is unreliable.’ Late Qing bronze-script scholar Fang Ruiyi (1815-1899) offers a more substantial theory with his research on bronze scripts. His research shows that Qi (杞) state was formed by the Si Clan, while the Qi (㠱) state was formed by the Jiang Clan, so are therefore two separate states. His study of the ‘Wangfu’ yi vessel in the Shanghai Museum concludes that Qi (㠱) is actually synonymous with Ji (紀) in the Classics. Unfortunately his book was not published until 1935, so his theory did not become influential until later. As an example, renowned oracle-bone script scholar Dong Zuobin (1895-1963) stated in his 1932 publication Jiaguwen duandai yanjiu li (‘Examples for dating Oracle bone scripts’) that ‘Marquis of Qi was written as 杞 in the time of King Wuding, but became 㠱 at the time of King Xing. 杞and 㠱are old and new forms of the same character.’ This is in line with Wei Hong’s claim. However in his 1936 publication Wudeng jue zai yinshang (‘Five Classes of Nobilities in the Shang Dynasty’), he switched to the view that Qi is synonymous with Ji in the Classics, very possibly influenced by Fang Ruiyi. Moreover, most philologists and historians in more recent times, such as Yang Shuda (1885-1956), Guo Moruo (1892-1978). Zeng Yigong (1903-1991), Chen Mengjia (1911-1966) etc., all agree with Fang Ruiyi’s theory.

The Qi State was formed by the Jiang clan, which was descended from Shennong the Yan Emperor, and was one of the ancient ‘Eight Great Surnames’. In the Baijiaxing (‘Hundred Surnames’) compiled in early Norther Song period, all of the five hundred surnames included were supposedly ‘descended from the Eight Great Surnames of Antiquity’. Ancient Chinese societies were matriarchal, and the character for ‘surname’, xing (姓), is written with the particle nü (女‘woman’) and sheng (生‘to give birth’), just as all Eight Great Surnames are written with a nü particle. There are two groupings of Eight Great Surnames, the first: Ji (姬), Jiang (姜), Si (姒), Ying (嬴), Yun (妘), Gui (媯), Yao (姚), Ji (姞); the second: Ji (姬), Jiang (姜), Si (姒), Ying (嬴), Yun (妘), Gui (媯), Yao (姚), Ren (妊). In matriarchal societies polyandry is practiced and a wife can have multiple husbands, so children have many fathers without knowing for certain which is the biological father. Interestingly, some societies in southern China still call their mothers die (爹 dad). The character die is written with the particle fu (父father) and duo (多many), and is how children called their mothers in ancient matriarchal societies.

It is said that during the time of the Yellow Emperor, men gradually became dominant in matrimony, but women still played an important role in society. For example, Fuhao, whose tomb was excavated in 1976 in Henan, was one of Shang Dynasty King Wuding’s many concubines, and became well-known to scholars because we were able to identify her from oracle bone inscriptions not only as a high level priestess, but also a combative female general who conquered many neighbouring states, a very unique case in history.

According to Diwang shiji (Chronicles of Emperors and Kings) written by historian Huangfu Mi (215-282) of Western Jin, the ancestor of Qi state, Shennong the Yan Emperor ‘... was surnamed Jiang. His mother was surnamed Rensi, daughter of Youqiao, and named Nüdeng. She once travelled to the south of Mt. Hua, and conceived Yan Emperor while strolling when she came in contact with a divine dragon. He was born with a human body and a buffalo head, grew up in the Jiang river and had great virtues. As fire follows wood, and he was born in the South, he was called Yan (inflame) Emperor. First he settled in Chen, then moved to Lu. He was also called Kuisou, Lianshan and Lieshan. He was emperor for 120 years before he passed away, and his dynasty lasted eight generations to Yugang, totalling 530 years. The Zhoushu recorded: During Shennong’s times, the heaven rained down grains, and Shennon planted and cultivated them. He also invented pottery and the axe. The Gushi kao recorded: The Yan Emperor corresponds to fire, so all his ministry and troops are named after fire. Lu Jing recorded in Dianyu: Shennong tasted all the herbs and distinguished those that bore grains, thereafter people started eating grains.’

Furthermore, it is recorded that Shennong‘…was the first to teach people to plant the five grains as food, so that killing can be averted. He tasted plants to distinguish those that can be used as medicine, thereby saving many from premature death or injury. Common people benefit from this daily while oblivious. He wrote four scrolls on herbology.’

This expounds on the tradition of Yan Emperor being the founder of Chinese medicine, and the first ever book of Chinese herbology, Bencaojing of the Han Dynasty, is also called Shennong Bencaojing.

In Shiji it is recorded: ‘The Shennong clan went into decline during the time of Xuanyuan.’ According to ancient accounts, the Shennong clan existed for over 500 years before the Yellow Emperor (of Xuanyuan clan) appeared. The Yellow Emperor rose to replace Shennong as the leader, and one of the tribes of the Shennong clan joined forces with the Yellow Emperor to defeat Chiyou in the Battle of Zhulu. Historian Xu Zhuoyun considers the amalgamation of Yan and Yellow Emperors’ tribes the beginning of the ancient Huaxia tribe. This is why the Huaxia people are known as the ‘offspring of Yan and Huang’, out of respect for these two figures.

Academic research is indeed daunting work with a vast amount of information to consider, however, with new excavations and progressive textual comparisons, I believe the history of ancient Qi State will gradually come to light. As an actual relic, the current white jade ‘Qihou Mi yong’ ge blade will no doubt shed new light, both in academia and in the collecting world, in the research of inscriptions on archaic jades..

Christie’s is also pleased to present a specially curated sale: Inspiring The Mind – Life Of A Scholar – Official which showcases works that reflect the refined and scholarly taste of the Chinese literati. The special sales features 68 works of art ranging from jade carvings, ritual bronze vessels, lacquer boxes, carved seals and rare furniture from Ming to early Qing Dynasty, with selection of works establishing an interesting dialogue between age-old literati traditions, and Zitan the spirit of today’s refined scholars. One of the top lots is a Magnificent And Extremely Rare Carved Zitan Hexagonal Table (Estimate HK$16,000,000 – 20,000,000). This table is very large in size and also unique in style, and is the only such example recorded, with its style comparable to Zitan furniture from the Qianlong period. For the enthusiasts of Chinese furniture, there is another top lot An Important and Very Rare Pair Of Huanghuali Round-Corner Tapered Cabinets And Stands, Yuanjiaogui (Estimate HK$16,000,000 – 20,000,000) .

Lot 2844. A Magnificent And Extremely Rare Carved Zitan Hexagonal Table, Qianlong period (1736-1795); 36 1/2 in. (92 cm.) high,, 44 3/4 in. (113 cm.) wide, 44 3/4 in. (113 cm.) deep. Estimate: HK$16,000,000 – 20,000,000 (USD 2,073,784 - USD 2,592,230). © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

The table top is constructed with six sides above a shallow waist that is decorated with a register of floral scrolls, and two further registers of lotus lappets and joined ruyi heads on the rounded shoulder. Each of the vertical sides is finely carved in shallow relief with large floral blooms growing on scroll-form vines, and skilfully concealing a drawer of trapezoid-form which can be neatly pulled by a metal ring at the centre. The corners of the table are supported by elegant tapering ‘dragonfly’ legs, each terminating in an upturned end of ruyi form. Set above the foot is a conforming hexagonal panel, sumptuously carved with floral blooms of varying sizes growing with leaves on long stems.

Provenance: Yamanaka & Co., by 1932

Hosokawa Moritatsu (1883-1970) Family Collection

Hierlooms of Chinese Art from the Hosokawa Clan, sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 8 October 2014, lot 3108.

Literature: Sekai kobijutsu tenrankai shashinshu, Photo Album of Antiques of the World exhibition, Yamanaka & Co., and Tokyo Art Club, Osaka and Tokyo, 1932.

Exhibited: Sekai kobijutsu tenrankai, Antiques of the World exhibition, Yamanaka & Co., and Tokyo Art Club, Osaka and Tokyo, 1932, Catalogue, no. 770

Sekai kobijutsu daitenkan, Grand Exhibition of the World Ancient Relics, Yamanaka & Co., Osaka, 1938, Catalogue, no. 193.

©Yamanaka & Co., Ltd., 1932, Antiques of the World exhibition

Note: Of all the forms in Chinese furniture, the square, rectangular (including those with canted corners) are the most common, followed by circular, and then the hexagonal, octagonal, quatri-lobed, cinque-lobed, hexa-lobed and the conjoined-lozenge form etc. As the forms became more complicated, the craftsmanship required became more demanding. These pieces with complicated forms were not only made to demonstrate the ultimate artistic skills that were achieved but they also served a functional purpose for their display locations. Take the current hexagonal table, for example, the inclusion of a drawer points to certain degree of frivolity and functionality, and it would have been placed in the centre of an important space where people can sit around it without the sitters having to distinguish their ranks. Its large size and unique style makes it the only such example. Most hexagonal or circular tables of this size were made with two independent halves, so that they can be used individually, and rarely have the gravitas of the current example.

The table top is made with six sections joined by invisible tenons, a common joinery in zitan furniture. The edge of the table top has a subtly tapered profile reducing to a single step towards the bottom edge, and looks very simple and elegant.

It has a relatively high waist, which is carved in relief with scrolling passion fruit blooms and acanthus leaves, each bloom accompanied by four leaves, giving the impression of four cartouches per each side of the waist. The step below the waist is carved with a band of lotus petals. This type of lotus petals are named in the Records (archival records of the imperial workshops known as the Zaobanchu) as the ‘badama’, a terminology that could be traced back to the Yuan Dynasty. The raised apron is carved with a band of cloud scrolls on the top edge, much like a brocade border. Although it is also relief carving, the carving style is quite different. Unlike the sharp carving of the previous bands, this is carved in a more rounded and fuller style, akin to carvings on rhinoceros horns, and acts to elongate the lotus band below the waist to give a more luxurious effect.

The legs are placed at the six corners, and each conforms to the angle of the corner with a ridge. The way they are joined to the aprons has the appearance of inserted-shoulder joints, but is actually done by embracing-shoulder tenons. Between the legs there are stretchers on both sides, uncarved except for beading on the edges. The space between the aprons, legs and stretchers are inserted with a drawer. The drawers, because of the hexagonal form of the table, are in trapezoid shape. Each of the drawer is fitted on the base with a piece of slider, which slots into the grooved baseplate. The face of each drawer is carved with passion fruit scrolls, the central quatrefoil bloom fitted with a chrysanthemum form metal plate and fish-form handle, flanked by meandering acanthus leaves. Below the stretchers there are pierced aprons of floral scrolls, each with three blooms joined by scrolling leaves.

The cabriole legs are derived from the ‘dragonfly legs’ of Ming-style furniture. The upper sections are decorated with furled leaves, the ‘wings’ of the dragonfly, and the legs taper in from this point to form the cabriole. The lower section of the legs are straight from this point, with the two edges beaded, and terminate in an up-curled ruyi head, corresponding to the ruyi heads on the apron and the curled leaves of the upper section. The ruyi terminal is carved plump, with a raised spine, corresponding to the ridge of the legs. There are stretchers below the legs supporting a reticulated footrest. The stretchers have aprons carved with scrolling clouds terminating in the centre with a large ruyi head.

The current table is very large in size and also unique in style, and is the only such example recorded. However, its form and style are comparable to many zitan furniture from the Qianlong period. For example, there is a pair of square zitan stands with cabriole legs decorated with passion fruit scrolls in the Palace Museum (fig. 1), which is closely related to the current table from the details on the legs, the waist, the aprons and the spandrels, even though the size and form are different. These stands are recorded to be displayed in the Shoukang Palace, together with four zitan chairs with passion fruit scrolls. The Shoukang Palace was home to the dowager empress Chongqing in the Qianlong period.

fig. 1 Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing.

The footrest panel is fitted recessed, with a beaded edge and canted corners. The passion fruit scroll, with a very balanced and classic composition and beautifully executed carving, is an exemplary Qianlong period carving of this genre. In the centre is a large passion fruit bloom with three rows of six petals, corresponding to the hexagonal form of the table. It is surrounded by curling acanthus leaves all around, dotted with buds and blooms, and rendered in various techniques such as relief, reticulated and incised carving to depict the leaves furling and unfurling. The luxurious carving coupled with the dark texture of the zitan produce a very noble effect overall.

The passion fruit scroll, composed of the passion fruit bloom, buds and acanthus leaves, is archetypical of the Rococo style. It was introduced to China in the early Qing period, and is also called ‘western bloom’ or ‘foreign bloom’. This exotic pattern was very popular with the Imperial court, and was used extensively on objects. Missionaries were drafted into the Palace to produce enamelled wares, porcelain and furniture so that these objects could be displayed in western style palaces. For example, the records show that on the 14th day, 6th month of 16th year of Qianlong, the emperor requested to:

“Replace the four lacquer incense stands on the western stage of Shuifa Palace. Order Lang Shining to draft a few of the same size in western style for preview.”

This table is a typical Imperial furniture made for the Palace. The Records of the Zaobanchu indicate that these zitan pieces of large size and quantity were mostly made by the Zaobanchu branch in the Guangzhou Customs office, either by Imperial command because zitan was mostly imported, or as tribute. The Guangzhou customs had abundant raw material because zitan was mostly imported, as well as a supply of capable craftsmen. In fact, many of the carpenters in the Yangxindian Zaobanchu were drafted from Guangzhou. Besides, missionaries often entered China through Guangzhou, there was a strong Western influence reflected in the works that were produced. Thus, the use of passion fruit scrolls was most successfully adapted on furniture made in Guangzhou. For example, on the 17th year of Qianlong, Ali Gun, the Governor of Hu Guang, and Li Yongbiao, the supervisor of Guangzhou Customs, sent as tribute ‘a pair of large zitan tables with hundred bats and western flowers, a set of 12 zitan chairs with foreign flowers, a pair of large zitan screens inset with glass, and a pair of zitan horizontal hanging panels with painted glass insets’. The ‘hundred bats and western flowers’ mentioned here are probably bats with lotus or passion fruit scrolls, while the ‘foreign flowers’ are likely also passion fruit scrolls.

The current table was once in the hands of renowned dealer Yamanaka & Co., and later included in the Hosokawa Moritatsu Family Collection. Yamanaka purchased a large amount of works of art from the residence of Prince Kung, including several furniture pieces that were published. The current table was included in Antiques of the World Exhibition in Tokyo, and published in 1932 (fig.2), followed by the Grand Exhibition of the World Ancient Relics in Tokyo, 1938 (fig.3). Hosokawa Moritatsu (1883-1970) was the founder of Eisei Bunko (Eisei Archive) in Tokyo that assembled 80,000 pieces of Eastern works of art. The lineage of Hosokawa clan dates back to 14th century in Kumamoto, Japan. It is worth mentioning that on the base of each of the drawer there is a stamped mark ‘made in China’- a mark commonly seen on export porcelain pieces in the late Qing dynasty, Guangxu period. Perhaps this table was sent overseas as an export piece at the time.

fig. 2 ©Yamanaka & Co., Ltd., 1932.

fig. 3 ©Yamanaka & Co., Ltd, 1938.

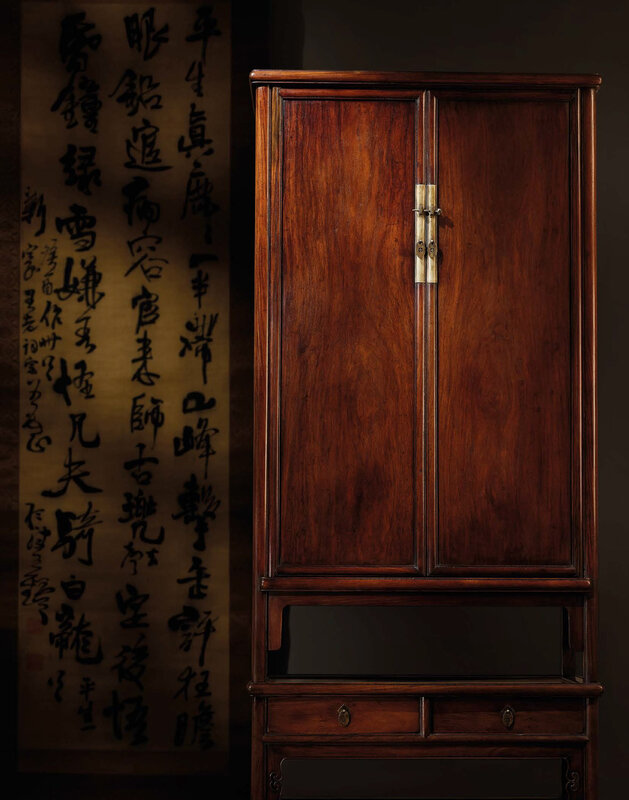

Lot 2810. An Important and Very Rare Pair Of Huanghuali Round-Corner Tapered Cabinets And Stands, Yuanjiaogui, Ming dynasty, 17th century; 73 1/4 in. (186 cm.) overall high, 34 5/8 in. (80.5 cm.) wide, 18 1/2 in. (47 cm.) deep. Estimate HKD 16,000,000 - HKD 20,000,000(USD 2,073,784 - USD 2,592,230). © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

Each cabinet is well-proportioned and constructed with a rounded, protruding, rectangular, double-cushion moulded top supported on slightly splayed corner posts of conforming shape. The figured floating-single panel doors are contained within rounded moulded frames and fitted with shaped lockplates and pulls. Each set of doors open to reveal a removable shelf, above a further shelf and two drawers. The cabinets are elegantly raised on matching stands with splayed legs double tenoned to the single plank top, each constructed with two drawers above a dovetailed stretcher. The horizontal plain apron with a beaded edge and the vertical sides with elegantly carved ruyi-shaped aprons.

Provenance: Dr S. Y. Yip, ‘Ming Furniture – the Dr S. Y. Yip Collection’ sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 7 October 2015, lot 115.

Literature: Grace Wu Bruce, Feast by a wine table reclining on a couch: The Dr. S. Y. Yip Collection of Classic Chinese Furniture III, Hong Kong, 2007, p.88-91

Grace Wu Bruce, Two Decades of Ming Furniture, Beijing, 2010, p. 223

Grace Wu Bruce, Ming Furniture Through My Eyes, Beijing, 2015, p. 227.

Exhibited: The Dr S. Y. Yip Collection of Classical Chinese Furniture, The Macau Museum of Art, Macau, 2003

Grace Wu Bruce, Feast by a wind table reclining on a couch: The Dr S. Y. Yip Collection of Classical Chinese Furniture III, Art Museum, Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, 2007, Catalogue no. 27, pp. 88-91

Grace Wu Bruce, Grace Wu Bruce Presents a Choice Selection of Ming Furniture from the Dr S. Y. Yip Collections, Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre, Hong Kong, 2012, pp. 38-39.

Note: The distinctive figuration on the four broad, single panels indicates that they were cut from the same piece of timber. The panels are fitted with the grain set at opposing mirror image, thus giving a sense of drama and motion to the cabinets. The careful matching of the doors suggests that the cabinet-maker intentionally designed the cabinets to feature the natural markings of the wood and had remarkable sensitivity with materials.

Of special note on the present cabinets is the original wood stands. The function of the wood stand is to raise and protect the furniture from having direct contact with the damp floor, which may have been used exclusively in the southern region of China with relatively high humidity. It is extremely rare to find cabinets retaining the original wood stand because this type of structure has been difficult to preserve as damage from moisture would be expected. In addition to the rarity, the planks on the likely damaged stands are also constructed in single panel huanghuali, showing off the extravagance of wealth to the most refined but subtle detail.

The present pair of cabinets stands out as a truly exquisite example of its type, all the rarer for being a pair. The gentle splay in its design lends a sense of stability and balance to the form while retaining a very graceful and pleasing profile. The simple but elegant form of these cabinets is the classic Ming style, characterised by the finely carved ruyi-form apron on the stands which is a typical design of the period. Such detail is also seen on the apron of a huanghuali square table dated to Ming dynasty (fig. 1) in the Beijing Palace Museum collection, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, Furniture of the Ming and Qing Dynasties (I), Hong Kong, 2002, p. 85, no. 69. Although the form of the present example was widely used in cabinet making throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties, only one published example of slightly lower height has retained its original stands, which is exhibited and illustrated in Splendor of Style: Classical Furniture from the Ming and Qing Dynasties, National Museum of History, Taipei, 1999, p. 160-161.

fig. 1. Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing

This item is made of a type of Dalbergia wood which is subject to CITES export/import restrictions since 2 January 2017. This item can only be shipped to addresses within Hong Kong or collected from our Hong Kong saleroom and office unless a CITES re-export permit is granted. Please contact the department for further information.

Finally, the Important Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art sale will feature a diverse offering of exquisite and rare ceramics, Buddhist art and statues, jade carvings, snuff bottles, among other works, and is sure to cater to a wider range of collecting tastes and collectors. The top lot of the sale is a A Pair Of Very Fine And Rare Yangcai Chrysanthemum Dishes (Estimate HK$15,000,000 – 20,000,000).

Lot 3004. A Pair Of Very Fine And Rare Yangcai Chrysanthemum Dishes, Yongzheng Six-Character Marks In Underglaze Blue Within Double-Circles And Of The Period (1723-1735); 6 3/8 in. (16.3 cm.) diam., box. Estimate: HKD 15,000,000 - HKD 20,000,000 (USD 1,944,173 - USD 2,592,230). © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

Each dish is moulded with twenty-four petals rising from a straight foot ring, and finely enamelled to the centre with two peony blossoms in pink and iron-red borne on branches with leaves in green enamels of graduated tones, amid magnolia branches and asters.

Provenance: Sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 27 May 2008, lot 1546.

Note: Flower forms were regularly adopted with great success by Chinese potters as early as the Song dynasty, one of the most successful examples of which being the Ru lotus-form warming bowl in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, illustrated in Grand View: Special Exhibition of Ju Ware from the Northern Sung Dynasty, Taipei, 2006, pp. 126-129, no.26. In the Yongzheng reign, the chrysanthemum form became especially popular with the court and was produced with a number of monochrome glazes, such as the twelve monochrome chrysanthemum dishes in the Palace Museum, Beijing, see The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, Monochrome Porcelain, Hong Kong, 1999, pp. 282-283. This form continued to find favour in the succeeding Qianlong period. It is interesting to note that the chrysanthemum form of the current dish has been slightly modified from that seen on monochrome wares. The number of petals has been reduced in a more gently undulating style. Undoubtedly these sensitive modifications were made in order that the form should complement the enamelled decoration without detracting from it.

The peony spray on the interior of the dish is delicately and realistically painted in a style reminiscent of the renowned court painter Yun Shouping (1633-1690), who in turn drew inspiration from Song-dynasty flower paintings, as demonstrated by one of his album paintings titled In imitation of the ancient (fig. 1), now housed in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, accession number: gu-hua-001195-00003.

fig. 1. Yun Shouping (1633–1690), Peonies, 17th century. Album leaves, ink and color on top of paper. Height: 26.3 cm; Width: 33.4 cm, Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei

The opaque white enamel allowed the decorator to build up and shade the petals of the flowers, when used in conjunction with the clear pink made from colloidal gold. These colours were developed by craftsmen in the imperial workshops during the reigns of the Kangxi and Yongzheng emperors. The porcelain decorator of these dishes has achieved a particularly pleasing counterpoint between the opaque colours of the flowers and the translucent colours of the leaves.

Two types of dishes from this group exist, one is moulded with twenty-four lobes, which are found in two size groups, with the present dish belonging to the smaller group ranging between 15.5-16.5 cm. in diameter, and a larger group measuring 23 cm. in diameter. The present pair of dishes appears to be the only examples in this size group and decorated with this design.

Other dishes of this smaller size group include two single dishes (fig. 2) in the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum: Porcelains with Cloisonne Enamel Decoration and Famille Rose Decoration, Hong Kong, 1999, nos. 58 and 59, which have a simpler composition with only one, but larger peony in full bloom in adjacent to a half-open bud; another in The Tianminlou Collection, illustrated in Chinese Porcelain: The S. C. Ko Tianminlou Collection, Hong Kong, 1987, no. 96, which has a similar composition to the Palace Museum examples; and a pair painted with chrysanthemums from the collections of T.Y. Chao and Shimentang, included in Qing Porcelain from a Private Collection, Eskenazi, London, 2012, no. 5.

fig. 2. Two Famille Roe Chrysanthemum Dishes, Yongzheng Six-Character Marks In Underglaze Blue Within Double-Circles And Of The Period (1723-1735), Collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing.

For dishes of the larger size group bearing almost identical design as the current dish, see an example sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 26 April 1998, lot 510, which may have formed a pair with another dish sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 30 November 2016, lot 3219.

The second type is moulded with narrower fluted lobes rising to a flat and everted rim with chrysanthemum to the centre, see two examples of this type in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, accession numbers: guci-015001 (17.3 cm.) and guci-015012 (17.1 cm.); and a pair from a Kyoto collection, sold at Sotheby’s Hong Kong, 8 October 2013, lot 203.

A further highlight of the sale is The Alexander Ding Bowl (Estimate: HK$6,000,000 – 8,000,000), which comes with an impeccable provenance. It was previously owned by William Cleverly Alexander (1840-1916), who was a wealthy banker and keen connoisseur and collector of Chinese and Japanese art, with a significant portion of his collection being later acquired by the revered collector Sir Percival David.

Lot 3001. The Alexander Ding Bowl. An extremely rare fine and large 'Ding' 'Lotus' Bowl, Late Northern Song-Jin dynasty, 11th - 12th century; 12. 3/8 in. (31.5 cm.) diam. Estimate: HKD 6,000,000 - HKD 8,000,000 (USD 777,669 - USD 1,036,892). © Christie's Images Ltd 2020.

The large bowl is superbly potted with straight upright sides rising from a short foot and flaring slightly at the rim. The interior is incised with a continuous lotus scroll comprising two large fully-opened blooms, another bloom turning into a pod in the centre, two large leaves and two leaves of arrowhead. The exterior is carved with four rows of lotus petals, each petal with a raised central ridge. The bowl is covered inside and out with a lustrous, ivory-toned glaze with the exception of the mouth rim, which is bound in copper.

Provenance: From the collection of William Cleverley Alexander (1840-1916), and later the Misses Alexander

Sold at Sotheby’s London, 6 May 1931, lot 48 (for £150)

Bought through Bluett & Sons, London (for £175).

Literature: R.L. Hobson and A.L. Hetherington, The Art of the Chinese Potter, London, 1923, pl. XLIV

Exhibited: Manchester City Art Gallery, 1913, no. 774.

This magnificent Ding ware bowl has a most prestigious provenance. It was previously in the collection of William Cleverly Alexander (1840-1916)(fig. 1), who was a wealthy banker and keen connoisseur and collector of Chinese and Japanese art. He was also an early patron of James McNeill Whistler, who painted portraits of Alexander’s daughters and devised decorative schemes for both his London home and his country house in Sussex. In his obituary for William Alexander in 1916 the British artist and critic Roger Fry noted the remarkable good taste which guided Alexander’s acquisition of the pieces in his collection. William Alexander collected Chinese ceramics and jades, was a member of the London Burlington Arts Club, and loaned items from his collection to a number of important exhibitions – including the exhibition held at the Burlington Arts Club in 1895. He loaned the current basin to the ground-breaking exhibition of Chinese Applied Art held at the City of Manchester Art Gallery in 1913 (see Catalogue of an exhibition of Chinese applied art: bronzes, pottery, porcelains, jades, embroideries, carpets, enamels, lacquers, etc., City of Manchester Art Gallery, 1913, cat. no. 774). Following his death, Alexander’s daughters bequeathed paintings from his collection to the National Gallery in London. In May 1931 his daughters sold Alexander’s Asian art at Sotheby’s London in a two-day sale – including the current bowl, which was sold as lot 48 and bought by the respected London dealers Bluett & Sons. Such was the quality of Alexander’s Chinese pieces that a significant portion of the collection was bought by the revered British collector Sir Percival David.

fig. 1. William Cleverly Alexander (1840-1916)

This impressive Ding ware bowl is not only beautiful, but also a remarkable achievement on the part of the Northern Song potter who created it. Open-ware vessels of this unusually large size are rare amongst Ding wares, and posed a particular challenge to the potters and kiln masters. Ding wares were fired in kilns known either as mantou kilns (bread bun kilns) or horse-shoe shaped kilns. These kilns were typical of north China in the Song dynasty and were cross-draught kilns capable of achieving the high temperatures - in the region of 1300oC - needed to fire the high alumina Ding ware clay successfully. The disadvantage of the mantou kilns was that they had a relatively small firing chamber, while the refined Ding white vessels needed to be protected from kiln debris by being placed in saggars (fire clay boxes), which took up additional space within the kiln. In order to allow the firing of more than one vessel within a single saggar, without leaving a disfiguring mark on either vessel, stepped setters and ‘L’-shaped ring setters were developed. The Ding wares could then be fired using the fushao upside-down method, in which the mouth rim of the vessel was wiped clean of glaze and it was fired upside-down, standing on its mouth rim. Thus, pieces of ascending size could be fired on a stepped setter, while dishes of the same size could be fired in the ‘L’-shaped ring setters.

The upside-down firing of a bowl of this size would, however, have been real test of the skill of both the potter and of the kiln master, since there would have been a significant risk of warping and/or cracking during firing. Given that, in addition to the attendant risks, the cost of fuel for firing the kilns was very high, and only a few large pieces could be fired at a time, the cost of manufacture for a vessel the size of the current bowl would have been considerable. It would not have been undertaken lightly, and would almost certainly have been in response to a specific order from an important patron. Consequently, Ding open-ware vessels of this large size are very rare.

The interior decoration on extant examples of these large bowls is predominantly either fish or lotus, while the exteriors can be plain, decorated with lotus scrolls, or, as in the case of the current bowl, carved with bands of low-relief over-lapping petals. It is likely that very few of these large bowls were ever successfully fired, and thus few extant examples have survived into the present day. An example with lotus on the interior and low-relief over-lapping petals on the exterior is in the National Museum of China, Beijing (see en.chnmuseum.cn/collections_577/collection_highlights_608/201911/t20191121_172679.html). A similarly decorated bowl (fig. 2) in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei is illustrated in Catalogue of the Special Exhibition of Ting Ware White Porcelain, Taipei, 1987, no. 32, while a bowl with lotus on the interior, but a plain exterior is illustrated in the same publication, no. 30. A large Ding ware bowl with lotus on the interior and lotus scroll on the exterior is in the collection of the Fujian Provincial Museum (illustrated in Zhongguo wenwu jinghua daquan - Taoci juan, Taipei, 1993, p. 270, no. 334). A further example with lotus on the interior and low-relief over-lapping petals on the exterior is in the collection of the Asian Art Museum. San Francisco, object number: B60P1491. Interestingly, a slightly smaller bowl with lotus on the interior but undecorated on the exterior was unearthed from a Korean, Koryo dynasty tomb dated AD 1152, at Kaesong, and is now in the Tokyo National Museum (see Teiyo hakuji (White Porcelain of Ding Yao), Nezu Bijutsukan, Tokyo, 1983, no. 121).

fig. 2. A 'Ding' 'Lotus' Bowl, Late Northern Song-Jin dynasty, Collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei.

Lotuses were an enduringly popular motif in all areas of the Chinese arts due to their links with Buddhism, purity, harmony and beauty. The best known of all the Chinese literary references to this flower is the work entitled On the Love of the Lotus (Ai lian shou) by the Song dynasty literatus Zhou Dunyi (1017-1073), who also expressed the Confucian idea that the lotus represented the ‘gentleman’ or ‘superior man’, junzi. In classical paintings all parts of the lotus – the flower buds, the flowers and their seed pods, and the leaves – are often all depicted. The fact that the lotus displays buds, flowers and seed pods at the same time is felt to represent the three stages of existence – past, present, and future. Such depictions are very rare on Song dynasty ceramics, and most Ding wares are decorated with lotus scrolls, or relatively simple flowers and leaves. The current bowl is especially rare in following the painting tradition and clearly showing the lotus seed pod as well as the flowers and leaves.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F63%2F62%2F119589%2F129821675_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F63%2F11%2F119589%2F129248500_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F90%2F07%2F119589%2F129178554_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F73%2F73%2F119589%2F129177195_o.jpg)