Around the World in Blue and White: Selections from the William C. Weese Collection of Chinese Ceramics at Michigan

ANN ARBOR, MICH.- The technology and taste for blue and white porcelain originated in China in the fourteenth century, and quickly set off a worldwide craze that lasted five hundred years. Installed across four different galleries at UMMA, this exhibition explores that history and tracks the influence of blue and white ceramics across the globe.

First commissioned by Muslim merchants living in China, blue and white porcelain found its way to Southeast and East Asia, the Middle East, the eastern coast of the African continent, and then to Europe and North and South America. In the Chinese gallery, a grand display of these highly coveted items. Many of them traveled from China to the Netherlands via Dutch East India Company ships, along with tea, silks, paintings, and other luxury items.

Beaker vase, Ming dynasty, circa 1640, porcelain with blue underglaze painting,17 3/4 in. (45.08 cm). Promised gift of William C. Weese, M.D., LSA ‘65. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

Dutch, Chinoiserie plate with four figures in a landscape, circa 1660, tin-glazed earthenware (delftware), 2 3/16 x 13 13/16 x 13 13/16 in. (5.4 x 35 x 35 cm);2 3/16 x 13 13/16 x 13 13/16 in. (5.4 x 35 x 35 cm);x 13 13/16 in. x 35 cm.The Paul Leroy Grigaut Memorial Collection. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

This Chinoiserie plate, made in the Dutch city of Delft in imitation of imported Chinese porcelain, depictsfour men sitting in a landscape. a stylized scene that evokes traditional Chinese images of scholars conversing in a natural setting. The figure seated under the arch holds an object in his lap that the leftmost figure leans forward to inspect more closely, while the man on the right looks away into the distance. The fourth figure, with his hands tucked into his sleeves, may represent a servant, although the artist who painted this plate was primarily concerned with imitating decorative effects, and was probably unaware of the differentiation of status made through careful distinctions of gesture and dress in Chinese painting.

Four men sit under a canopied arch in a Chinese-style landscape with pine trees and a river in the well of this blue-and-white plate. The figure seated under the center of the arch holds an object on his lap, which the leftmost figure leans forward to inspect more closely. The old man who sits at the right of the group looks off to his right. The paneled border of the rim is decorated with four reserves featuring the figure of a seated Chinese man. The reserves are separated by a pair of narrow panels flanking a larger central panel. The narrow panels contain a stylized flower motif, while the larger panels are decorated with more elaborate floral designs.

Chinese, Charger, 1662 - 1722 (Qing dynasty, Kangxi reign), porcelain with cobalt underglaze and clear glaze, 2 3/8 in. (6.03 cm). Promised gift of William C. Weese, M.D., LSA ‘65. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

This charger is decorated with a blooming lotus flower radiating from the center to the rim. In each separate petal, a branch of flower is depicted. This design is evocative of mural paintings on ceilings in Buddhist caves.

A blue and white plate centered with a circular panel containing a blossoming lotus encircled by two borders of lappets containing flowering plants, with a shaped rim. There is a studio mark within a double circle on the base.

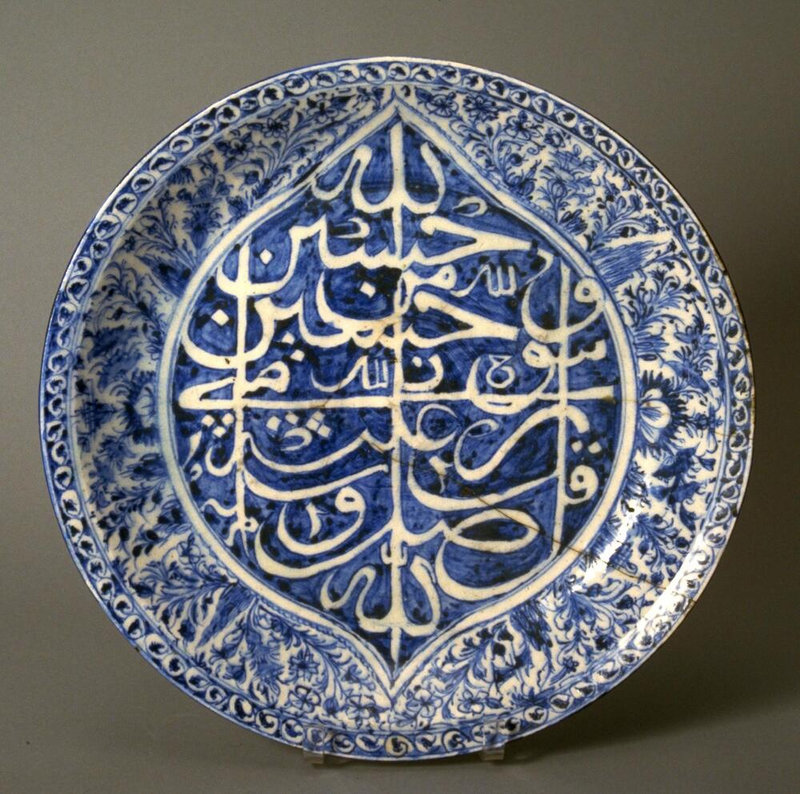

Ali ibn al-Hajj Muhammad, Platter with an inscription from a Hadith [a saying of the Prophet Muhammad], signed by Ali ibn al-Hajj Muhammad, 17th century - 18th century, fritware with underglaze painting, and clear glaze, 2 15/16 in x 17 ¾ in x 17 ¾ in (7.5 cm x 45.1 cm x 45.1 cm);2 15/16 in (7.5 cm);x 17 ¾ in x 17 ¾ in x 45.1 cm x 45.1 cm. Transfer from the College of Architecture and Design, 1972/2.158. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

This platter represents the perfect marriage of Persian and Chinese aesthetics. It was the Chinese who originated blue-and-white porcelain in the fourteenth century, using cobalt imported from western Asia for the blue pigment. Such wares were eagerly collected in Islamic cultures of the Middle East, where they were often imitated, as here, in fritware. The style and palette of this platter, as well as the potter’s signature on the back, indicate it was made in Kirman, a city in southern Iran. A Chinese-inspired floral scroll opens to create a central medallion space, where a large inscription in Thuluth script is reserved in white from the blue background. The inscribed text is a well-known Shi’ite hadith—one of the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad—that honors his descendants Hassan and Hussein. The illusion of filigree-work in the medallion recalls the pierced steel standards carried during the mourning ritual processions that commemorate the martyrdom of Hussein. Given this content, it is likely that the potter crafted this magnificent, unusually large platter to donate to a religious institution, perhaps a mausoleum, where it would have been displayed in a niche.

The central decoration contains a medallion in a pointed oval shape featuring a fragment of a hadith, or saying of the Prophet Muhammad. The rim is decorated with foliage, which grows from the edge of the medallion. There is a signature on the center of the foot which attributes Ali ibn al-Hajj Muhammad as the artist. Comparable objects attribute this to Kirman, Iran.

Vase, Qing dynasty (18th century), soft paste porcelain with blue underglaze painting, 15 1/2 in. (39.37 cm). Promised gift of William C. Weese, M.D., LSA ‘65. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

Ceramic Screen in Wood Frame, Qing dynasty (early 19th century), porcelain with blue underglaze painting and wood,17 x 11 3/4 in. (43.18 x 29.85 cm). Promised gift of William C. Weese, M.D., LSA ‘65. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

Blue and white porcelain screen, showing mountains, bridge with travelers, trees, mounted into rosewood frame decorated with blossoming lotus vines and scrolled ends probably made in the late 19th century. Since 16th century, it is increasingly popular to have painted porcelain slabs inlay in furniture, small screens, or wall decors. By the 19th century, porcelain screens had become highly marketable cultural items.

Soup Tureen with Platter and Lid, 19th century, porcelain, 9 1/4 x 12 x 9 in. (23.5 x 30.48 x 22.86 cm). Gift of William C. Weese, M.D., LSA '65. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

Japanese blue and white porcelains rose to prominence as replacements of Chinese porcelains in the early 17th century, and continued to be popular exports in the European market. In the Japanese gallery, porcelains in various forms and decorations that show mutual inspirations of the two global brands.

Japanese. Blue-and-white jar with floral and leaf design, 1615-1643, porcelain, blue underglaze painting, 8 9/16 in x 7 ½ in x 7 ½ in (21.7 cm x 19 cm x 19 cm);12 ½ in x 9 ¾ in x 10 ½ in (31.75 cm x 24.77 cm x 26.68 cm). Museum purchase made possible by the Margaret Watson Parker Art Collection Fund. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

A medium size, well potted jar with round shoulder and shorter neck. Inside is not totally glazed. On the body, pine, bamboo, and plum trees are finely painted with blue underglaze. Then a translucent glaze is applied, which turns into milky, white color. It has three floral decorations on the shoulder; the decoration is originated in functional elements of “ears” to which ropes were tied for transportation. The neck has a band of double lines and spray design of peony flowers and leaves. The rim of the neck is unglazed. The foot is unglazed; eye is glazed. Some imperfections of glaze are seen toward the bottom. Glaze is scraped off on one part. Many speckles on the surface.

The three plants depicted here, pine, bamboo, and plum, are called “three friends in winter,” and have been depicted in many forms of Japanese decorative arts throughout its history. They symbolize long life and cultured gentlemen.

Ceramic traditions and technologies have moved back and forth across Asia since the prehistoric period, a phenomenon that continues to this day. This piece dates from the very beginning of porcelain production in Japan, made possible by the forced immigration of a great number of Korean potters following the Japanese invasion under the military leader Toyotomi Hideyoshi (1536–1598). The more technically advanced Korean potters introduced the noborigama (climbing kilns), multichambered wood-fired kilns that can retain a high, accurate, and evenly distributed temperature. The discovery of a large deposit of prized kaolin, or porcelain clay, in the province of Hizen further contributed to the rise of porcelain making in Japan.

The combination of pine, bamboo, and plum blossom—known as the “three friends”—is a popular motif across the decorative arts of East Asia.

Japanese. Covered Imari jar with scene of young woman playing a koto, 1820-1850, porcelain, blue underglaze and enamel overglaze, 16 9/16 in. x 9 7/16 in. ( 42 cm x 24 cm ). Gift of the William T. and Dora G. Hunter Collection. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

Kondô Yûzô, Blue-and-white jar with pomegranate design, circa 1960. Porcelain with blue underglaze painting, 7 5/16 in x 6 5/16 in x 6 5/16 in (18.57 cm x 16.03 cm x 16.03 cm);7 5/16 in x 6 5/16 in x 6 5/16 in (18.57 cm x 16.03 cm x 16.03 cm). Museum Purchase. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

It is a medium size porcelain vase with pomegranate design in blue underglaze. The body is round with gentle shoulders; the mouth is wide and the neck is short and slightly inward. It has no foot. The pomegranate fruit and leaves are quickly executed with broad brush around the shoulder and the middle of the body. There is a band of a single line around the mouth and another around near the bottom. There is the artist’s signature “yû” on the eye. There is no foot but unglazed ring around the bottom; the eye is glazed.

Pomegranate is a popular motif in East Asian art, as it blessed with many seeds, represents the wish for numerous progeny and the attainment of sexual maturity by a woman (Reference: Baird, Merrily, Symbols of Japan: Thematic Motifs in Art and Design.)

In the late eighteenth century, Kyoto potters adopted blue-and-white porcelain, originated by Korean potters in Hizen province. While Hizen’s pottery center, Arita, catered to the mass market, Kyoto produced high-quality copies of Chinese blue-and-white wares for upper-class banquets and tea ceremonies.

While the initial interest of twentieth-century potters in pre-modern ceramics centered on robust, warm-glazed wares like Shino and Oribe, or non-glazed wares like Bizen and Shigaraki, in the postwar period many potters were drawn to smooth and polished stonewares and porcelain. Among them, Katô Hajime was recognized for his incomparable passion for the great stoneware and porcelain traditions of China and the Middle East, as well as for his superb technique. This large white bowl, thinly potted to perfection, has a witty carved design of baby quails.

For the Kyoto potter Kondô Yûzô, the pure white surface of porcelain was an ideal canvas for vividly rendering subjects from nature. He once said: “In my pottery, I try to achieve the life that naturally fills the shapes of fruits and plants from mountains and fields, to express their freshness, vibrant power, their grace, and their rigor.”

Chinese blue and white porcelains have been exported to Korea since the early 15th century. Korean kilns also produced regional porcelains with expensive cobalt imported from China. In the Korean gallery, a magnificent dragon jar and scholarly implements used by social elites.

Korean. Blue-and-white balustrade jar with design of stag, crane, and pine tree, late 19th century, porcelain with blue and iron brown underglaze painting, 13 5/8 x 10 7/16 x 10 7/16 in. (34.6 x 26.5 x 26.5 cm). Transfer from the College of Architecture and Design. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

This Korean jar is porcelain, which requires a special type of clay and a kiln capable of very high temperatures. Korea has an abundance of fine-grained clay suitable for porcelain wares. Inspired by Chinese blue-and-white ceramics, Korean potters made use of both rare imported cobalt (for blue) and local iron and copper (for brown and red) to produce pigments for underglaze painting. But while Chinese potters preferred tightly organized patterns, in Korean pots exuberant pictorial designs cover the entire surface of the vessel. The vocabulary of motifs is uniquely Korean as well: here, every plant and animal is an auspicious symbol of longevity.

Choson dynasty porcelains were much appreciated in Japan for their robust shapes and the powerful, spontaneous drawing of the underglaze designs.

Korean. Blue-and-white jar with dragon-and-cloud design, 19thcentury, porcelain with cobalt pigment under colorless glaze, 9 1/2 x 7 7/8 x 7 7/8 in. (24 x 20 x 20 cm). Gift of Bruce and Inta Hasenkamp and Museum purchase made possible by Elder and Mrs. Sang-Yong Nam. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

Large porcelain jar decorated with cobalt pigment under colorless glaze. Repeating clouds border the rim of the jar, while a dragon head and feet are depicted on the main body below. Two blue bands separate the design from the white base below, balancing the rim and bottom portion of the jar. The very tip and base of the piece are also marked with blue bands.

This is a blue-and-white jar with cloud and dragon designs which is tought to have been produced at Bunwon-ri, Gwangju-si, Gyeonggi-do around the year1883, when official court kilns there were privatized. The dragon is painted with cobalt on a large jar, but with only its head fully exposed and the body largely concealed by white clouds. This distinctive design is rarely found in blue-and-white porcelain. Two blue horizontal lines encircle the rim, while its shoulder features a yeoui-head band. It is glazed all the way down to the outer base, and coarse sand was used as kiln spurs, which leaves its mark on the foot rim. The Chinese character “白” (“baek;” white) is incised on the outer base. Specks of ash on the jar’s surface give it an overall pale yellow tint.

Korean. Blue-and-white Ritual Dish with Inscription "Je (祭)", 19th century, porcelain with blue underglaze painting, 2 1/2 x 6 3/4 x 6 3/4 in. (6.3 x 17 x 17 cm). Gift of Bruce and Inta Hasenkamp and Museum purchase made possible by Elder and Mrs. Sang-Yong Nam. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

The upper surface of this vessel features a circle with the Chinese character "je (祭: ancestral rite)" rendered inside in cobalt blue pigment. The tray features blemishes, while the rims show traces of use. The foot retains traces of coarse sand supports stuck to it during firing. This type of ritual vessel has been excavated from the upper sediment layers of waste deposits of kilns in front of what is now Bunwon-ri Elementary School in Gwangju-si, Gyeonggi-do. Such vessels are presumed to have been produced immediately before the Bunwon-ri kiln cloised down and to have been widely supplied to the general public.

Thailand and Vietnam long produced their own local versions of expensive Chinese blue and white porcelains. In the South and Southeast Asian gallery, fascinating examples of these copies using clay and glaze local to those regions. In addition, salvaged pots from a late 17th century shipwreck tell the story of the vibrant global market and fervent demand for blue and white ceramics.

Covered box with a knob and alternating panels of vegetal scrolls and lattices, Thailand, circa 15th century, stoneware with underglaze iron decoration and clear glaze 3 3/4 x 3 15/16 x 3 15/16 in. (9.5 x 9.9 x 10 cm);3 3/4 x 3 15/16 x 3 15/16 in. (9.5 x 9.9 x 10 cm);2 3/8 x 3 15/16 x 3 15/16 in. (6 x 9.9 x 10 cm);1 1/2 x 3 15/16 x 3 15/16 in. (3.8 x 9.9 x 10 cm). Gift of the Marvin Felheim Collection. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

Small-size covered box, the lotus bud handle and surrounding medallion in brown, the body and lid with alternating panels of vegetal scrolls and lattices. Each panel is separated by a raised line. The foot is painted brown. Clear glaze.

These small covered boxes were created in kilns at Sawankhalok, the largest ceramic production site in Thailand. It is situated by the Yom River, which provides easy access to the port for the Southeast Asian island trade. From the thirteenth to sixteenth centuries, Sawankhalok was the major competitor to the kilns in Vietnam and Southern China. While Vietnam successfully produced inexpensive copies of Chinese blue underglazed porcelains, Thai kilns adopted the Chinese designs but used iron (which results in a brown color) in place of cobalt oxide for underglazing. Though this covered box with leaf scroll and lattice design shares the sensibility of Chinese and Vietnamese blue-underglaze wares, the brown color gives it a rustic feeling.

Covered boxes were used as burial objects to accompany the dead. This practice for the care of deceased people in afterlife preceded the succession of foreign religious influence from Buddhism, Hinduism to Islam. The stoneware trade ceramics were also objects of status and wealth, for the local kilns only produced less durable and inexpensive earthernwares. The round shape with a handle, and some of the design motifs were adopted from stone and metal reliquaries and architectural elements came with Indian Hinduism and Buddhism.

Kendi, 15th-16th century, stoneware with cobalt underglaze painting, 5 3/4 in. (14.61 cm). Promised gift of William C. Weese, M.D., LSA ‘65. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

A green vessel, or kendi, with a flat oval body with a wide spout on the side that sharply thins at the tip. The neck at the top of the kendi's body is long and suddenly widens at the rim. The outside is decorated with geometric designs.

A kendi is pouring vessel with a spout on the side but without a handle. While pouring, the pot is held around its neck. Pouring vessels of this kind is not found at all in China before the Song dynasty where the earliest types seems to have been straight spouted vessels with South Chinese brown-black Jian type glaze.

During Yuan dynasty, white types with creamy white glaze over moulded decorations also with straight spouts, occurs in South Chinese export wares. In South East Asia, kendis seem to have had all the uses a pouring vessel with a spout could possibly have from medication, drinking, washing, blessing to sacrificial. Its main use seems to have been as a water drinking vessel, where many persons hygienically and without using any cups could share one water bottle by drinking directly from the stream coming from its spout when tilted.

Blue-and-white covered box with floral and geometric designs, Vietnam, 16th century, stoneware with blue underglaze painting, 1 15/16 in. x 3 in. x 3 in. ( 4.9 cm x 7.6 cm x 7.6 cm ). Museum purchase made possible by the Margaret Watson Parker Art Collection Fund. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

A melon-shaped stoneware box with a lid, the shape slightly faceted on the sides and the lid concave to a disk-shape center. The box is decorated with freehand floral and geometric designs in blue cobalt pigment, and then a whitish glaze was applied to the whole.

These covered boxes with blue underglaze painting are examples of the prime wares exported from Vietnam to the Southeast Asian island countries. Although blue-and-white stonewares were first produced exclusively in China, increasing demand from the international market made the Vietnamese kilns highly competitive in the production of less expensive types. Not unlike the international car industry in the modern era, it was common for these kilns to copy their rivals’ popular models and sell them at cheaper prices. Blue-and-white shards of Chinese Ming wares have been found at kiln sites in Vietnam and in Thailand, another major competitor.

Covered boxes were used as burial objects to accompany the dead. This practice for the care of deceased people in afterlife preceded the succession of foreign religious influence from Buddhism, Hinduism to Islam. The stoneware trade ceramics were also objects of status and wealth, for the local kilns only produced less durable and inexpensive earthernwares. The round shape with a handle, and some of the design motifs were adopted from stone and metal reliquaries and architectural elements came with Indian Hinduism and Buddhism.

Blue-and-white small lidded jar with three lug handles, Vietnam, 16th century, stoneware with blue underglaze painting, 3 3/8 in. x 3 3/4 in. x 3 3/4 in. ( 8.5 cm x 9.6 cm x 9.6 cm ). Museum purchase made possible by the Margaret Watson Parker Art Collection Fund. ©2022 Regents of the University of Michigan.

A small, slightly squat, globular stoneware jar, resting on a broad and short foot, with a short, narrow neck rising to hold a slightly domed lid. There are three small lug handles at the shoulder, allowing the jar to be carried by a cord. The jar is decorated with three horizontal zones of decoration, either floral or abstract designs drawn freehand in cobalt blue pigment before a translucent glaze was applied to the entire vessel.

Steven Young Lee, Icon, porcelain, cobalt inlay, and glaze, 2019. University of Michigan Museum of Art, Museum purchase made possible by the William C. Weese, M.D. Endowment for Ceramic Arts, 2021/1.127.A-S. Courtesy the artist and Duane Reed Gallery © Stephen Young Lee

Steven Young Lee is a contemporary American ceramic artist who interrogates the history and symbolic meaning of blue and white ware. In Icon, he combines an image of Bruce Lee, an iconic Hollywood movie star of East Asian descent, and the dragon and flower-scroll motifs ubiquitous in many exported blue and white wares. The images of Lee and the dragons are fractured across nineteen small circular plates, as if to suggest the distance between the reality of Asia/Asians and how they are imagined in American consciousness.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F98%2F60%2F119589%2F129446628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F76%2F45%2F119589%2F128507375_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F50%2F93%2F119589%2F128266925_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F72%2F27%2F119589%2F127838123_o.jpg)