Life and Afterlife in Ancient Egypt at the Art Institute of Chicago

CHICAGO - The transformed space explores aspects of life and the afterlife in the Nile Valley with the first new installation of works from the museum’s historic collection of ancient Egyptian art in a quarter-century. Striking artifacts—displayed along one wall of the gallery in a series of innovative cases that promote viewing from multiple vantage points—provide insight into the beliefs and practices of this illustrious North African culture.

Recurring themes throughout this fresh presentation of the collection consider the impact of Egypt’s natural environment, including the Nile River, on its visual culture; reveal the processes of ancient Egyptian artists; and explore the centrality of gods and goddesses to life (and death) along the Nile. Arresting sculptures, such as the statue of Shebenhor, reveal how ancient Egyptians chose to present themselves so that they would be remembered for eternity, while funerary works—such as a gilded funerary mask—unveil practices for preparing for and protecting oneself in the afterlife.

Opening Feb 11, 2022

Model of a River Boat, Egypt, Middle Kingdom, Dynasty 11–12, about 2046–1794 BCE. Wood and pigment, 63.5 × 114.3 × 17.1 cm. Gift of Henry H. Getty, Charles L. Hutchinson, Robert H. Fleming, and Norman W. Harris, 1894.241, Art Institute of Chicago

In the Middle Kingdom, tomb paintings and statues were often supplemented with wooden models. This boat is fully equipped with a crew, oars, and a mast. It was thought that the model could provide the soul of the deceased not only with routine transportation, but also with the ability to make the pilgrimage to the sacred city of Abydos in southern Egypt, the cult center of the god Osiris.

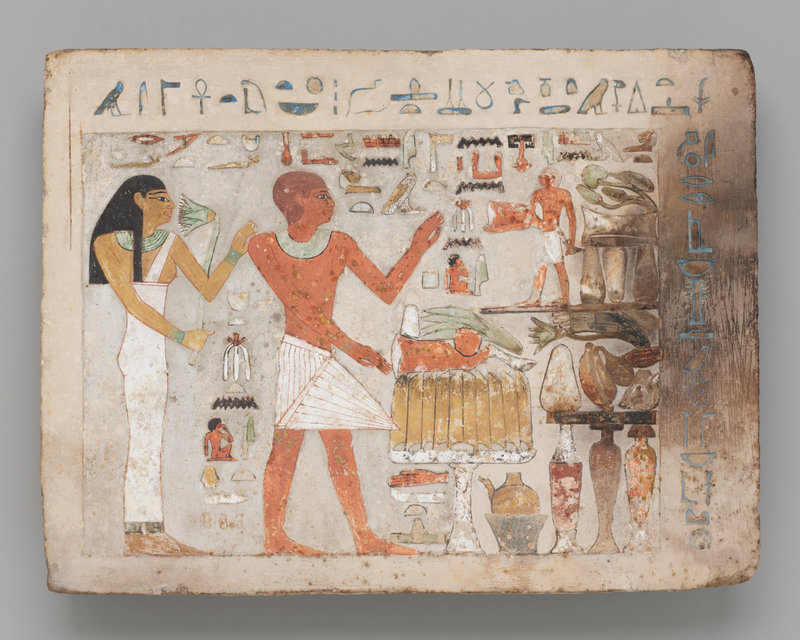

Stela of Amenemhat and Hemet, probably Thebes (now Luxor), Egypt, Middle Kingdom, early Dynasty 12, about 1956–1877 BCE. Limestone and pigment, 31.1 × 41.7 × 6.7 cm. Museum Purchase Fund, 1920.262, Art Institute of Chicago

This stela was colored with a mixture of pigment and tempera. First, however, it was sculpted in raised and sunken relief; only later were some of its surfaces embellished with black, brown, green, yellow, and white paint. It commemorates for all eternity a man named Amenemhat and his wife, Hemet. Before them are two offering tables stacked with food. Their son appears in the upper right at a smaller scale. In addition to the hieroglyphs in the field, a brief text also appears on the top and right border.

Egyptian art is highly symbolic. The left side of the composition is the dominant position; the placement there of Amenemhat and Hemet conveys their importance. He stands in front of his wife, stressing that he is the head of the household. The social difference between them is indicated by the color of their skin. His is dark reddish brown and hers is yellow; he is active outdoors, while the home is her realm. They both wear traditional clothing and jewelry.

The goal of the artist was to immortalize the essential elements of his subjects. This representation reflects conventions for portraying the human form as a composite diagram made up of different views. Amenemhat and Hemet are shown with their heads in profile, their shoulders frontal, and their chests, buttocks, and legs in profile. These positions offered the most characteristic and comprehensive views of the human form. Also, depth is represented by height, so the offerings at the top of the composition should be understood as the farthest away.

The brightly colored, raised-relief hieroglyphs within the scene record the names of the subjects, their lineage, and voice offerings, which refer to the belief that offerings could consist of actual food, images of food, written references to it, or the recitation of prayers that call for provisions. Carved in sunken relief and painted blue, hieroglyphs along the top and right record a conventional prayer for food to sustain Amenemhat and Hemet in the afterlife.

Kohl Container in the Shape of a Palm Column, Egypt, New Kingdom, mid–Dynasty 18 or early Dynasty 19, about 1352–1213 BCE. Core-formed glass, 8.2 × 3.0 × 3.0 cm. Gift of Theodore W. and Frances S. Robinson, 1941.1084, Art Institute of Chicago

Glassworking in Egypt appeared suddenly as a fully developed industry under the pharaohs of the Eighteenth Dynasty (1550–1295 BCE) and was probably imported from the older glass centers of the Eastern Mediterranean. During this time glass production was restricted to a handful of workshops producing vessels and objects intended only for the pharaoh and his court. In addition to small glass objects such as beads, amulets, and inlays, the new industry produced a wide variety of glass vessels for unguents, incense, and cosmetics. Particularly popular were vessels like this example made to contain kohl, a black pigment used by both men and women to outline their eyes. The kohl was applied with a thin rod, and the containers were sealed with stoppers made of linen and wax. The shape of this object recalls a palm column, a traditional element of Egyptian architecture. The bright, opaque colors of these early core-formed glass vessels—dark blue, turquoise blue, red, yellow, and white—seem to emulate semiprecious stones such as lapis lazuli, turquoise, and jasper. The rarity of these glass works (only some five hundred complete examples are known) indicates that they were precious commodities.

Statuette of Re-Horakhty, Egypt, Third Intermediate Period-Late Period, Dynasty 21–26, about 1069–525 BC. Copper alloy with gilding, 25 × 8.3 × 10.5 cm. Gift of Henry H. Getty, Charles L. Hutchinson, and Robert H. Fleming, 1894.261, Art Institute of Chicago.

Inscriptions: "Re Horakhty, chief of the gods."

Here Re-Horakhty, a combination of the solar gods Re and Horakhty, strides forward in the form of a falcon-headed male. He is identifiable by his falcon head (once crowned with a sun disk inserted into the hole at the top of his head) and the golden hieroglyphs at the center of his belt, which read, “Re-Horakhty, Chief of the Gods.” Re-Horakhty was worshipped throughout Egypt but was particularly revered in Iunu, an ancient city located near modern Cairo that the Greeks called Heliopolis (“city of the sun”) in his honor. Statuettes of deities such as this one were set up in temples and shrines to receive offerings or presented to the gods as gifts that were later ceremonially buried.

Statue of Shebenhor, Memphis, Egypt, Late Period, Dynasty 26 (664-525 BCE). Basalt, 28 × 13 × 16.3 cm. Gift of Mrs. George L. Otis, 1924.754, Art Institute of Chicago

Inscriptions. Front: “A gift the king gives and that Osiris the Great gives [to] Bastet the Great, Mistress of Bubastis, that she might give offerings from Upper Egypt and provisions from Lower Egypt to the ka of the one revered before Atum, Lord of Kaheref, Shebenhor, justified, son of Hedeb-Hapi-ir-bin, born of Iachays-nakht.” Back: “A gift the king gives [to] Bastet the Great, Mistress of Bubastis, that she might give invocation offerings consisting of bread, beer, oxen, fowl, and every good thing to the ka of the one revered before Atum, Lord of Kaheref, Shebenhor, justified.”

Shebenhor’s heavy, round “bag wig” was fashionable at the time this statue was carved. The splayed toes, broad shoulders, and exaggerated narrowness of the waist are also characteristic of Egyptian statues of this era. Statues of individuals were placed in temples to maintain a connection between the dedicator and the god. The statue was capable of eternally transferring the blessings of the god to the individual.

Statue of Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, Egypt, Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE). Wood, preparation layer, pigment, gold, and textile, 62.9 × 12.7 × 27.3 cm. Gift of Phoenix Ancient Art, S.A., 2002.542, Art Institute of Chicago.

This vibrantly painted statue represents the ancient Egyptian funerary deity Ptah-Sokar-Osiris. The god is depicted in the form of a mummy with red linen wrappings covered by an intricate net of multicolored beads. The statue would have been placed in the tomb of its owner, a woman named Ese-ir-di-es (“Isis is the one who gave her”). Columns of hieroglyphic text on the front and back state that she will be provided with the offerings necessary for her continued survival in the afterlife, including food and drink.

Plaque Depicting a Quail Chick, Egypt, Ptolemaic Period (332–30 BCE). Limestone, 12 × 13.2 × 1.3 cm. Museum Purchase Fund, 1920.256, Art Institute of Chicago

Remarkable for its lifelike detail, this plaque depicts a fledgling quail, better known to literate Egyptians as the hieroglyph for the sound w. Plaques like this one that show animals, deities, and royalty were a relatively late addition to the ancient Egyptian artistic repertoire, first appearing around 664 BCE. Their function remains a mystery—they may have been used as sculptors’ models in the training of artists, dedicated in temples as gifts to the gods, or perhaps both.

Portrait of a Man Wearing a Laurel Wreath, The Fayum, Egypt, Roman Period, early to mid–2nd century. Lime (linden) wood, beeswax, pigments, gold, textile, and natural resin, 39.4 × 22 × 0.2 cm depth with support 3.5 cm. Gift of Emily Crane Chadbourne, 1922.4798, Art Institute of Chicago

This portrait belongs to a large group of similar works known as “Fayum portraits,” so-named for the region in northern Egypt in which many have been discovered. To create this man’s likeness, the artist painted a thin piece of wood with encaustic, or pigmented wax, a medium that not only gave the impression of three-dimensionality but also resisted fading and deterioration in the dry climate of Egypt. These highly individualized and lifelike portraits conveyed the wealth and status of the person depicted through clothing, jewelry, and other embellishments, such as the gold wreath of ivy worn by this man.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F22%2F18%2F119589%2F122439819_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F48%2F02%2F119589%2F122336662_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F67%2F72%2F119589%2F122304559_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F66%2F119589%2F31440582_o.jpg)