Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy on view at the Getty Research Institute, Getty Center, February 22–July 10, 2022

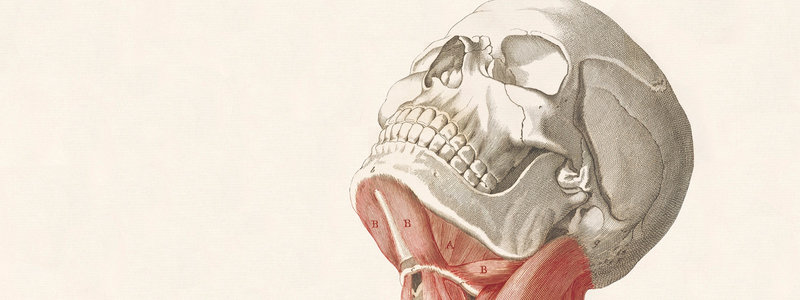

Muscles of the Neck (detail). Etching and engraving inked à la poupée in red and black, in Giuseppe del Medico, Anatomia per uso dei pittori e scultori (Rome, 1811), pl. 16, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles (84- B28069)

For centuries, artists and scientists have been fascinated by the structures of the human body.

Featuring works of art from the 16th century to today, the Getty Research Institute exhibition Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy explores the theme of anatomy and art and the impact of anatomy on the study of art.

“Flesh and Bones celebrates the connection between art and science and the role of art in learning,” said Mary Miller, director of the Getty Research Institute. “This exhibition draws on the Getty Research Institute’s rich and varied holdings to tell the story of two disciplines that have long been intertwined. I believe visitors will find meaningful connections with the way artists and scientists have inspired one another for centuries.”

Love & Hate, August 19, 2012, OG Abel (Abel Izaguirre). Graphite on paper, 12 1/2 × 19 1/2 × 3 in. Getty Research Institute, 2013.M.8. Gift of Ed and Brandy Sweeney © OG Abel

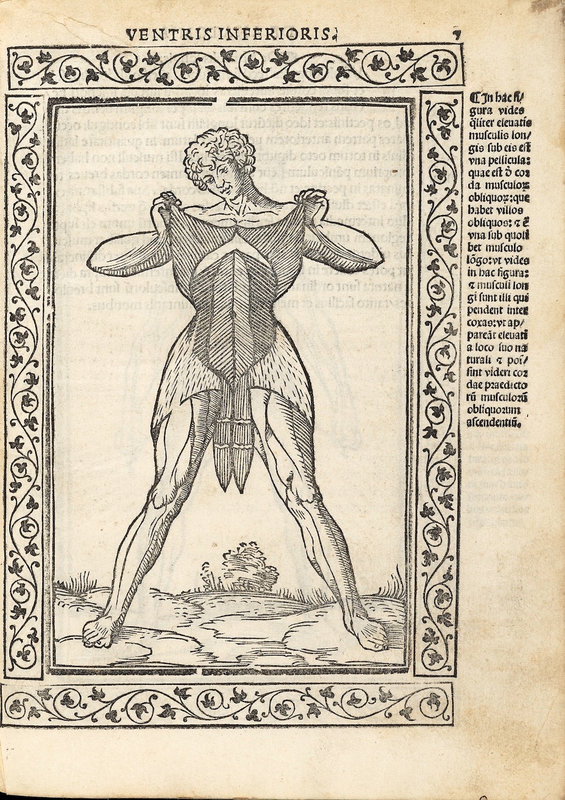

From spectacular life-size illustrations to delicate paper flaps that lift to reveal the body's interior, the body is represented through a range of media. In Europe, the first printed anatomical atlases, introduced during the Renaissance, provided new visual maps to the body, often composed of striking images. Landmarks of anatomical illustration such as the revolutionary publications of Vesalius in the 16th century and Albinus in the 18th century are represented as well as little-known rarities such as a pocket-size book of anatomy for artists from over 200 years ago.

The exhibition, which explores important trends in the depiction of human anatomy and reflects the shared interest in the structure of human body by medical practitioners and artists, is organized by six themes: Anatomy for Artists; Anatomy and the Antique; Lifesize; Surface Anatomy; Three Dimensionality; and The Living Dead. The last looks at the motif of the representation of the dead as living, with skeletons and anatomized cadavers capable of motion rather than inert on a dissecting table.

Figure displaying the muscles of the abdomen. From Jacopo Berengario da Carpi, Isagogae breves perlucidae ac uberrimae in anatomiam humani corporis …, 2nd ed. (Bologna, 1523), fol. 7r. Getty Research Institute, 84-B28214

For artists of the modern era, anatomy is often a medium of expression and a signifier of the body itself, rather than purely an object of study. Robert Rauschenberg’s Booster (1967) and Tavares Strachan’s Robert (2018) are two life-size anatomical portraits as well as symbols of the passing nature of life. Echoing the composite prints of Antonio Cattani’s remarkable life-size anatomical figures from the 1700s in the exhibition, Booster is a fractured self-portrait based on X-rays of the artist that have been joined together.

Abdominal dissection with detail of the gall bladder, after Jan Steven van Calcar. From Andreas Vesalius, De humani corporis fabrica libri septem (Basel, 1543), p. 365 [465]. Getty Research Institute, 84-B27611

Strachan’s Robert is not an exact likeness of the man it immortalizes, Major Robert Henry Lawrence Jr., the first African American astronaut, who tragically died in a training accident. In choosing to represent the hidden interior of the body in neon and glass, Strachan, a former GRI artist in residence, makes visible the unique history of Lawrence, while demonstrating an inner structure that equalizes all people.

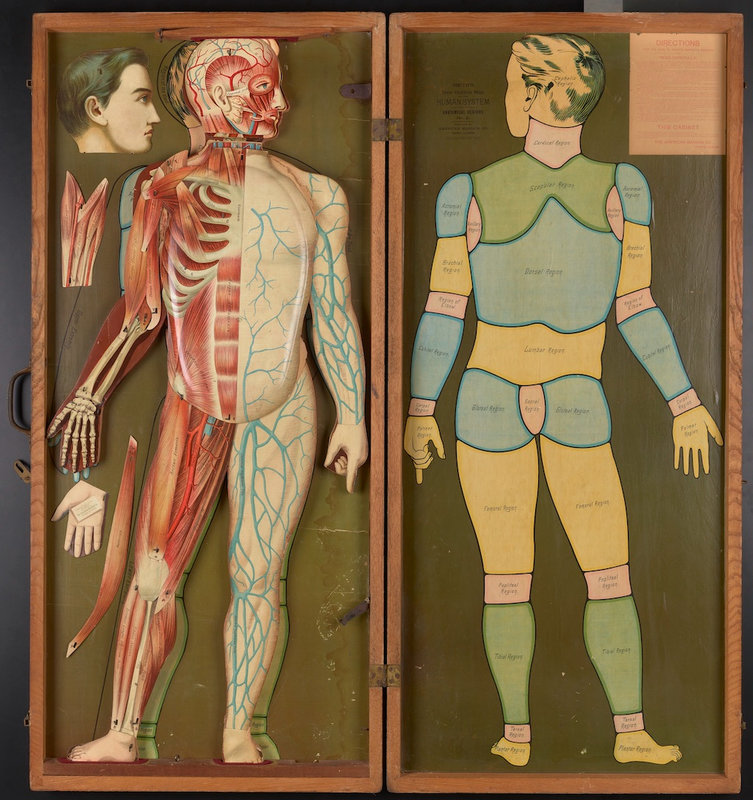

Anatomists and artists have approached the problem of how best to describe the body’s complex and invisible interior with a variety of representational strategies, ranging from the graphic to the sculptural and, recently, the virtual. From paper-flap constructions that allow viewers to lift and peer under layers of flesh to stereoscopic photographs that mimic binocular perception and project anatomical structures into space, three-dimensionality was inventively pursued in the pre-digital age to cultivate an understanding of anatomy as a synthetic whole.

The exhibition is curated by Monique Kornell, guest curator; guest assistant professor, Program in the History of Medicine, Cedars-Sinai Hospital, Los Angeles, and is accompanied by the richly illustrated publication Flesh and Bones: The Art of Anatomy, edited by Kornell and published by the Getty Research Institute.

Academy of Painters, about 1600, Pietro Francesco Alberti. Getty Research Institute, 2721-731.

The Muscles of the Eye in its Natural Position and the Muscle of the Eyelid, Shown Separately. From Thomas Bartholin, Anatome ex omnium veterum recentiorumque observationibus, 5th rev. ed. (Leiden, 1686), p. 507, pl. 9. Getty Research Institute, 93-B10050.

Dissected legs walking in a landscape, by 1616, Francesco Valesio after Odoardo Fialetti. From Giulio Casseri, Tabulae anatomicae, book 4, pp. 90-91, pl. 31, in Adriaan van den Spiegel, Opera quae extant, omnia (Amsterdam, 1645). Getty Research Institute, 84-B2833.

Tableau of fetal skeletons, Cornelis Huyberts. From Frederik Ruysch, Thesaurus anatomicus tertius (Amsterdam, 1703), pl. 1. Getty Research Institute, 94-B12267.

Life-size anatomical figure, seen from the front (one of a set of three) (detail), 1780, Antonio Cattani. Getty Research Institute, 2014.PR.17.

Life-size anatomical figure, seen from the front (one of a set of three), 1780, Antonio Cattani. Getty Research Institute, 2014.PR.17.

Life-size dissected woman (detail), 1750, Jacques Fabien Gautier Dagoty. From Jacques Fabien Gautier Dagoty, Anatomie générale des viscères en situation, de grandeur et couleur naturelle, avec l'angeologie, et la neurologie de chaque partie du corps humain (Paris, [1752]), pls. 1–3. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino.

Life-size dissected woman, 1750, Jacques Fabien Gautier Dagoty. From Jacques Fabien Gautier Dagoty, Anatomie générale des viscères en situation, de grandeur et couleur naturelle, avec l'angeologie, et la neurologie de chaque partie du corps humain (Paris, [1752]), pls. 1–3. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino.

The head of the Apollo Belvedere, rendered anatomically, Nikolaj Utkin after Jean Galbert Salvage. From Jean Galbert Salvage, Anatomie du gladiateur combattant, applicable aux Beaux Arts (Paris, 1812), pl. 1. Getty Research Institute, 85-B12146.

Dissection of chest and abdomen, Thomas Sinclair after Joseph Maclise. From Joseph Maclise, Surgical Anatomy (Philadelphia, 1851), pl. 26. Getty Research Institute, 1373-163.

Smith's New Outline Map of the Human System, 1888, American Manikin Co. Peoria, IL. Biomedical Library. Library Special Collections for Medicine and the Sciences, Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library, UCLA.

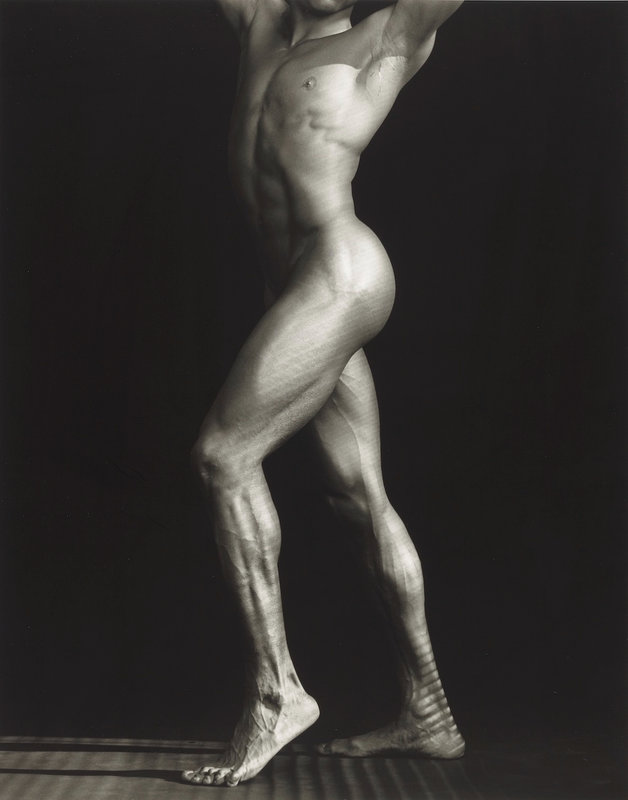

Ken Moody, negative 1985, print 2011, Robert Mapplethorpe. Gift of the Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation to the J. Paul Getty Trust and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. © Robert Mapplethorpe Foundation. 2012.52.10.

Robert, 2018, Tavares Strachan. Photo: Andrea D’altoè Neonlauro. Photo courtesy the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240309%2Fob_46fcb2_exposition-mapplethorpe-a-la-galerie-r.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F81%2F119589%2F121270258_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F64%2F24%2F119589%2F113154811_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F21%2F11%2F119589%2F111706210_o.jpg)