Exhibition at Kunstmuseum Basel retraces the dialogue between Picasso and El Greco

Attributed to Alonso Sánchez Coello, Lady in a Fur Wrap, c. 1577-79. Oil on canvas, 62 x 50 cm, Glasgow Life (Glasgow Museums) on behalf of Glasgow City Council, the Stirling Maxwell Collection.

BASEL.- A grand special exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Basel turns the spotlight on Pablo Picasso’s (1881–1973) engagement with the art of the Cretan-born Old Master Doménikos Theotokópoulos, better known as El Greco (1541–1614). With around thirty pairs of masterworks by both artists, it retraces their dialogue, one of the most fascinating such colloquies in the history of art. A core set of works by Picasso from the museum’s own collection is complemented by first-rate loans from all over the world.

Pablo Picasso helped set the course of European art history at several key junctures. Few artists enjoy greater international renown; few have been subject to more exhaustive scholarship. And yet hitherto unnoticed aspects of his oeuvre still await discovery. For example, it is well known that Picasso’s enthusiasm for El Greco has left marked traces in his work. Yet discussions of this relationship typically focus on the early stages of his career, up to and including the Blue Period. Picasso—El Greco proposes a fresh perspective, one in which the artist’s immersion in El Greco’s art was not only a good deal more intense than has been assumed, it also went on for much longer: its effects are clearly discernible both in his Cubist paintings and in works from all subsequent periods in his oeuvre.

The exhibition at the Kunstmuseum Basel | Neubau stages a focused and occasionally associative encounter in which Picasso and one of his heroes speak directly to each other across the centuries.

Pablo Picasso, Mme Canals (Benedetta Bianco), 1905. Oil and charcoal on canvas, 90 x 70 cm. Museo Picasso, Barcelona © Succession Picasso, 2022 ProLitteris, Zurich

Rehabilitating El Greco

El Greco, who was born in Crete in 1541 and arrived in Spain in the late 1570s after ten years in Venice and Rome, won considerable fame in his lifetime with his singular painterly style. Yet his star faded fairly soon after his death. It was not until the nineteenth century and again around the turn of the twentieth that El Greco renaissances swept Europe, making him popular with the continent’s artists. The young Picasso was instrumental to this rediscovery.

Picasso’s interest in the Greek Old Master was aroused in the final years of the nineteenth century, after his family settled in Barcelona in 1896. The aspiring painter— then only fifteen years old—associated with liberal-minded artists who took a leading part in rehabilitating the forgotten genius of El Greco. In 1898, Spain was defeated in the Spanish-American War and lost its last remaining major colonial possessions. In response to the former colonial power’s geopolitical decline, many in Spain’s cultural scene looked to the so-called “Siglo de Oro,” Spain’s “Golden Age” from the late sixteenth century to the end of the seventeenth, for inspiration. Nationalist sentiment ran high around 1900, and the painters of the Spanish school—led by El Greco, Diego Velázquez, and Francisco de Goya—became central figures as the country struggled to reclaim its identity.

As one of the great individualists in the history of European painting, El Greco was profoundly unconventional, in no small part because his itinerant early years had allowed him to familiarize himself with three different traditions (Greek-Byzantine, Venetian, and Spanish art), which he absorbed and transmuted into his own singular visual idiom. The dearth of documentary evidence on his life and art has added to his allure, which still has art lovers spellbound. His personality shrouded in legend, he was a perfect blank screen on which artists who rebelled against academic strictures projected their ambitions.

Pablo Picasso, Self-Portrait, 1901. Oil on canvas, 81 x 60 cm, Musée national Picasso, Paris. Photo: RMN-Grand Palais/Mathieu Rabeau © Succession Picasso, 2021 ProLitteris, Zurich

Picasso’s fascination with Spanish Old Masters

Picasso borrowed directly from El Greco from the very beginning of his career: numerous sketches from 1898–99 show him wrestling with motifs from the Old Master. His Portrait of a Stranger in the Style of El Greco (1899) reproduces a type of head that is characteristic of El Greco’s portraits and depictions of saints such as the Saint Hieronymus (ca. 1610) from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Similarly, the intimate masterwork The Burial of Casagemas (Evocation), painted in 1901, which marks the inception of Picasso’s Blue Period, is directly inspired by El Greco. The latter’s influence remains palpable over the following years: examples include the striking parallels between Picasso’s Portrait of Mme Canals (1905) and a Portrait of a Lady in Fur that was then attributed to El Greco; its authorship is now considered uncertain.

A second focus of the exhibition will be on Picasso’s Cubist period: two full galleries are dedicated to confrontations between his works from around 1910 and a selection from El Greco’s celebrated series of apostles (ca. 1608/1614) from the Museo del Greco, Toledo, and his large-format Resurrection of Christ (1597–1600) from the Prado, Madrid.

After the Second World War, Picasso—by now world-famous—devoted himself with newfound zeal to the paintings of the Old Masters. The exhibition showcases fascinating examples of his engagement with his artistic forebears, including the painting Musketeer (1967): the note “Domenico Theotocopulos van Rijn da Silva” in the artist’s hand on the back of the canvas is an explicit reference to his revered masters El Greco, Rembrandt, and Velázquez.

El Greco (Theotokopoulos, Domenikos), Portrait of an old man, ca. 1595-1600. Oil on canvas, 52.7 x 46.7 cm, The Metropolitain Museum, New York.

First-rate loans

In addition to a dozen key works by Picasso from the Kunstmuseum Basel’s collection, Picasso—El Greco presents over fifty outstanding works on loan from museums and private collections all over the world. The most important lenders are the Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid; the Museo del Greco, Toledo; the Museu Picasso, Barcelona; and the Musée national Picasso, Paris, which have kindly provided us with sets of key works from their collections. Additional important loans come from the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York; the National Gallery, Washington, D.C.; the National Gallery and the Tate Modern, London; the Musée du Louvre and the Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris; the Museo ThyssenBornemisza, Madrid; the Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest; and the Gemäldegalerie, Berlin.

An extensive catalogue accompanying the exhibition, with contributions by Gabriel Dette, Carmen Giménez, Josef Helfenstein, Javier Portús, and Richard Shiff, will be published by Hatje Cantz Verlag.

Pablo Picasso, Portrait of a Man after El Greco, circa 1899. Oil on canvas, 37.4 x 31.2 cm, Museo Picasso, Barcelona © Succession Picasso, 2022 ProLitteris, Zurich

El Greco (Theotokopoulos, Domenikos), Saint Jerome as a scholar, circa 1610. Oil on canvas, 108 x 89 cm, The Metropolitain Museum, New York, Robert Lehman Collection.

Pablo Picasso, Evocation (The Funeral of Casagemas'), 1901. Oil on canvas, 150 x 90 cm, Musée d'Art Moderne de la ville de Paris © Succession Picasso, 2022 ProLitteris, Zurich

El Greco (Theotokopoulos, Domenikos), The Adoration of the Name of Jesus, circa 1577/79. Oil on canvas, 140 x 109.5 cm, Patrimonio Nacional, Royal Monasterio de San Lorenzo de El Escorial.

Pablo Picasso, Homme, femme et enfant, Paris, Autumn 1906. Oil on canvas, 115.7 x 88.9 cm, Inv. 1967.11, Kunstmuseum Basel, Foto: Martin P. Bühler.

El Greco (Theotokopoulos, Domenikos), The Holy Family with St. Anne and the Infant John, circa 1600. Oil on canvas, 107 x 68.5 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

Pablo Picasso, Homme, femme et enfant, 1907. Oil on cardboard, 53.5 x 36.2 cm, Musée national Picasso, Paris. © Succession Picasso, 2021 ProLitteris, Zurich.

El Greco (Theotokopoulos, Domenikos), The Virgin Mary, circa 1590. Oil on canvas, 53 x 37 cm, Musée des Beaux Arts de Strasbourg.

Pablo Picasso, Sitting nude, 1909-10. Oil on canvas, 92.1 x 73 cm, Tate Modern, London © Succession Picasso, 2021 ProLitteris, Zurich.

El Greco (Theotokopoulos, Domenikos), The Penitent Magdalene, circa 1580/85. Oil on canvas, 101.6 x 82.9 cm. The Nelson Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, Missouri.

Pablo Picasso, The Musketeer (Domenicos Theotocopoulos van Rijn da Silva), 1967. Oil on plywood, 101 x 81.5 cm, Ludwig Museum of Contemporary Art, Budapest © Succession Picasso, 2021 ProLitteris, Zurich.

El Greco (Theotokopoulos, Domenikos), Portrait of a man from the Leiva noble family, circa 1580/85. Oil on canvas, 87.8 x 69.5 cm. The Montreal Museum of Fine Art, Adaline Van Horne Bequest.

Pablo Picasso, Le couple, 10 juin 1967. Oil on canvas, 195 x 130 cm, © Succession Picasso, 2021 ProLitteris, Zurich.

El Greco (Theotokopoulos, Domenikos), Christ takes leave of his mother, circa 1595. Oil on canvas, 131 x 83 cm. Museo de Santa Cruz de Toledo.

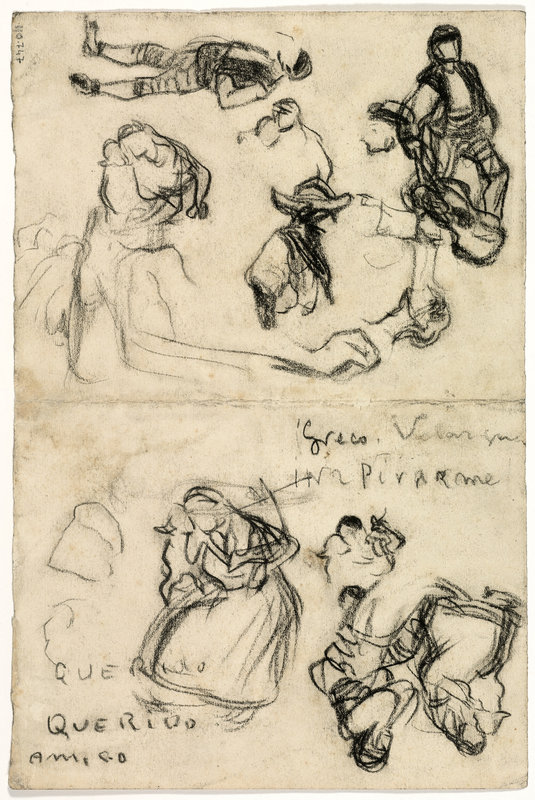

Pablo Picasso, "Greco, Velázquez, INSPIRARME" (Various Horta-Typen), 1898/1899. Conté pencil on paper, 24.3 x 16.2 cm, Museo Picasso, Barcelona © Succession Picasso, 2021 ProLitteris, Zurich.

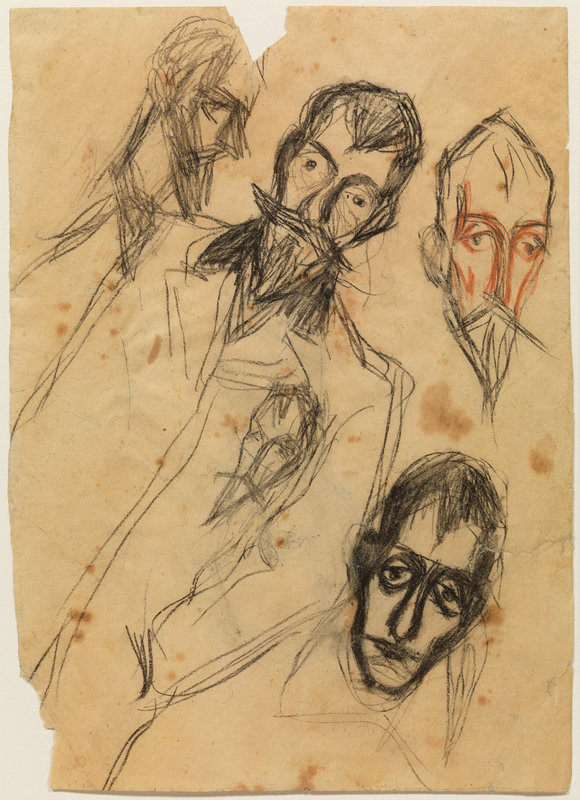

Pablo Picasso, Five Sketches of Figures in the Style of El Greco, circa 1899. Conté pencil and red chalk on paper, 30.6 x 22 cm, Museo Picasso, Barcelona © Succession Picasso, 2021 ProLitteris, Zurich.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F13%2F37%2F119589%2F129678618_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F37%2F14%2F119589%2F120640525_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F00%2F84%2F119589%2F111932108_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F22%2F02%2F119589%2F111454616_o.jpg)