First Major Exhibition on Afro-Hispanic Painter Juan de Pareja, to Open at The Met

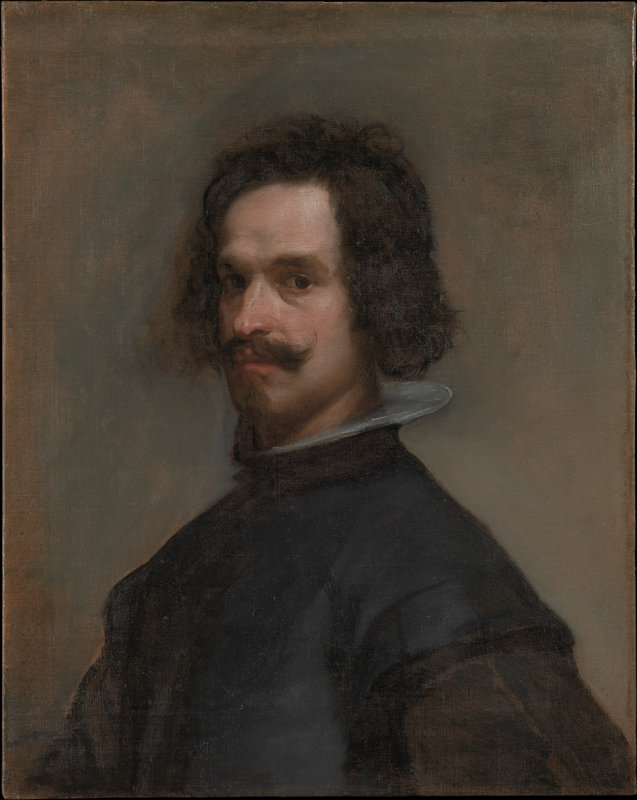

Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, Seville 1599–1660 Madrid), Juan de Pareja (ca. 1608–1670), 1650. Oil on canvas, 81.3 x 69.9 cm. Purchase, Fletcher and Rogers Funds, and Bequest of Miss Adelaide Milton de Groot (1876-1967), by exchange, supplemented by gifts from friends of the Museum, 1971, 1971.86. © 2000–2023 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Juan de Pareja, Afro-Hispanic Painter offers an unprecedented look at the life and artistic achievements of Juan de Pareja (ca. 1608–1670). Largely known today as the subject of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s iconic portrait by Diego Velázquez, Pareja was enslaved in Velázquez’s studio for more than two decades before becoming an artist in his own right. Opening April 3, 2023, this exhibition is the first to tell his story and examine the ways in which enslaved artisanal labor and a multiracial society are inextricably linked with the art and material culture of Spain's “Golden Age.” The presentation brings together approximately 40 paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts objects, as well as an array of books and historic documents, from The Met’s holdings and other collections in the United States and Europe.

The exhibition is made possible by the Sherman Fairchild Foundation.

Major support is provided by Denise Sobel.

Additional funding is provided by Laura and John Arnold, Fundación María Cristina Masaveu Peterson, Ann M. Spruill and Daniel H. Cantwell, and The Met’s Fund for Diverse Art Histories.

This exhibition is supported by an indemnity from the Federal Council on the Arts and the Humanities.

“This exhibition takes us to the very heart of 17th-century Spanish painting to reveal Juan de Pareja’s incredible personal story,” said Max Hollein, Marina Kellen French Director of The Met. “By reexamining the narrative around one of the most celebrated works in the history of western portraiture, the presentation challenges us to question existing notions about historical art and objects—and introduces a remarkable artist whose name may be familiar to many but whose work had not been explored in depth.”

In the exhibition, representations of Spain’s Black and Morisco populations in works by Francisco de Zurbarán, Bartolomé Estebán Murillo, and Velázquez join works that chart the ubiquity of enslaved labor across media. The Met’s portrait, executed by Velázquez in Rome in 1650, is contextualized by his other portraits from this period and the original manumission document freeing Pareja. The exhibition culminates in the first gathering of Pareja’s rarely seen paintings, including his self-portrait, featured in his vast The Calling of Saint Matthew (Museo Nacional del Prado). Additionally, the collection and writings of Harlem Renaissance figure Arturo Schomburg—who was vital to the recovery of Pareja’s work—serve as a thread connecting 17th-century Spain with 20th-century New York.

David Pullins, exhibition co-curator and Associate Curator in The Met’s Department of European Paintings, said, “The Met’s purchase of Velázquez’s painting in 1971 made headlines at the time, but scholars and the press said practically nothing about the man depicted. Not only does this exhibition shed more light on Pareja’s life but it also places emphasis on his agency as a creative force through his long overlooked paintings. Fleshing out Pareja’s story acts as a kind of wedge that makes space for entirely new narratives about the art and material culture of 17th-century Spain.”

Vanessa K. Valdés, exhibition co-curator and Associate Provost for Community Engagement and Professor of Spanish and Portuguese at The City College of New York, added, “Pareja’s artistic legacy reverberates across the canons of Western art and the African diaspora into our time. This project follows in the footsteps of Arturo Schomburg and joins the efforts of scholars who continue to recover the contributions of all peoples of African descent, including those of Afro-Hispanic heritage like Pareja, in order to better understand the full complexity and richness of the global Black experience.”

Exhibition Overview

Juan de Pareja, Afro-Hispanic Painter is organized thematically into four sections.

Pareja’s New York story began long before his portrait arrived at The Met. During the 1910s, as part of a broader project to recover evidence of excellence within global Black history, Schomburg pioneered a new understanding of Pareja. A Black Puerto Rican intellectual and collector who lived in New York, Schomburg traveled to Europe, spending time first in Seville, Granada, and Madrid, where he conducted research that reconstructed the multiracial society of Pareja’s time in which people of African descent had played a crucial, unrecognized part. The exhibition’s first section highlights Schomburg’s work through a core group of loans from The New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture and other sources, including his landmark essay “The Negro Digs Up His Past,” photographs from his travels, and several books. Quotations from Schomburg woven throughout the remaining galleries emphasize the central role that retrieval plays in the rewriting of received histories.

Pareja was born around 1608 in Antequera, Spain, probably to an enslaved woman of African descent and a white Spaniard. Although no known documents from Pareja’s lifetime speculate on his family origins or skin color, archival records from 17th-century Spain offer ample evidence of a multiracial society in which artists and artisans engaged enslaved labor. The exhibition’s second section illuminates the oft-obscured traces of enslaved labor in surviving objects from the era, demonstrated in polychrome wooden sculptures and other examples of woodwork, silverwork, and ceramics. Rare depictions of the region’s Black and Morisco (Spanish Muslims forced to convert to Catholicism) populations include a monumental painting by Francisco de Zurbarán (The Met). Three surviving versions of Velázquez’s painting of a kitchen maid—gathered together for the first time in this exhibition (from The National Gallery of Ireland; The Art Institute of Chicago; and The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston)—center a person of color as the composition’s primary protagonist. This unprecedented configuration in European painting attests to the burgeoning market for such images during that period, a market which Bartolomé Estebán Murillo would later cater to in his painting Three Boys (Trustees of the Dulwich Picture Gallery).

Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, Seville 1599–1660 Madrid), Kitchen Maid with the Supper at Emmaus, ca. 1617. Oil on canvas, 55 × 118 cm, The National Gallery of Ireland, Dublin.

Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, Seville 1599–1660 Madrid), Kitchen Maid, ca. 1618. Oil on canvas, 55.9 × 104.2 cm, The Art Institute of Chicago.

Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, Seville 1599–1660 Madrid), Kitchen Maid, ca. 1618. Oil on canvas, 86.4 × 73 cm, The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Harris Masterson III.

The exhibition’s third section focuses on the trip between 1649 and 1651 that Velázquez and Pareja took to Italy, where Velázquez painted his portrait of Pareja. Exhibited to great acclaim, the image paved the way for Velázquez to create an extraordinary series of portraits, including those of the papal retinue and friends. Velázquez’s portrait of Pareja secured a peculiar kind of celebrity for its subject and raises important questions about the relationship between portraitist and sitter when one is legally owned by the other. The trip was a turning point in Pareja’s professional and personal life: his enslaved status perversely afforded him rare access to monuments of European art that would inform his artistic voice. Velázquez also signed manumission papers (Archivio di Stato di Roma) in Rome, documenting his decision to free Pareja four years later and opening the door for Pareja’s choice to pursue his own career as a painter after their return to Madrid.

The exhibition concludes with the first-ever gathering of Pareja’s paintings, some of enormous scale, made after his manumission in 1654. By placing himself in dialogue with a group of artists known today as the Madrid School, whose lively palettes and compositions contrasted with Velázquez’s courtly sobriety, Pareja charted his own artistic path rather than following the style of his former enslaver. On display are The Calling of Saint Matthew (Museo Nacional del Prado), which includes a self-portrait on the far left; The Flight into Egypt (The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art); Portrait of José Ratés (Museu de Belles Arts de València); and The Baptism of Christ (Museo Nacional del Prado). The latter features a trompe l’oeil “carving” of Pareja’s name into a rock, his most adamant claim to artistic authority. The gathering of these works marks a new chapter in the continued recovery of Pareja’s art.

Juan de Pareja (Spanish, Antequera 1606–1670 Madrid), The Calling of Saint Matthew, 1661. Oil on canvas, 225 × 325 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

Juan de Pareja (Spanish, Antequera 1606–1670 Madrid), The Flight into Egypt, 1658. Oil on canvas, 168.9 × 125.4 cm, The John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, Sarasota, Florida.

Juan de Pareja (Spanish, Antequera 1606–1670 Madrid), The Baptism of Christ, 1667. Oil on canvas, 229 × 353 cm, Museo Nacional del Prado, Madrid.

Juan de Pareja, Afro-Hispanic Painter is co-curated by David Pullins, Associate Curator in The Met’s Department of European Paintings, and guest curator Vanessa K. Valdés, Associate Provost for Community Engagement and Professor of Spanish and Portuguese at The City College of New York. The exhibition took shape in dialogue with an external advisory committee.

A fully illustrated catalogue accompanies the exhibition. Published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and distributed by Yale University Press, it is available for purchase from The Met Store.

The catalogue is made possible by Denise Sobel.

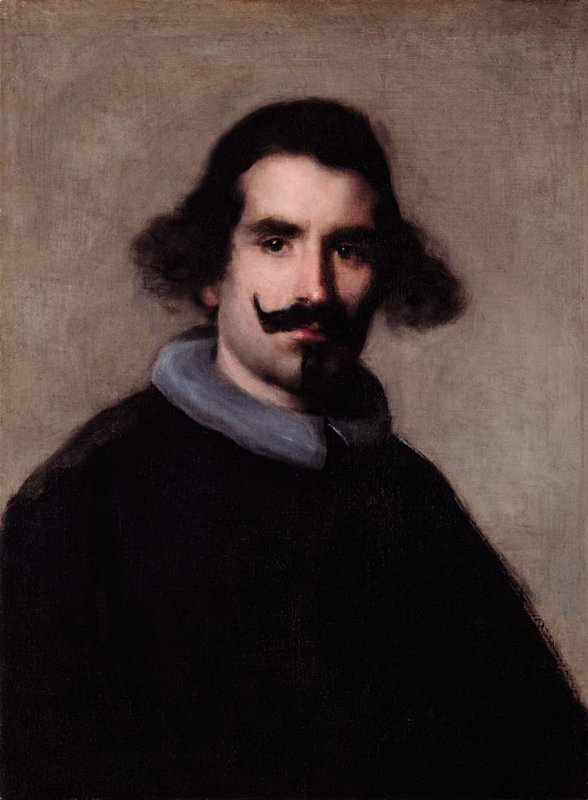

Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, Seville 1599–1660 Madrid), Portrait of a Man, Possibly a Self-Portrait, ca. 1635. Oil on canvas, 68.6 x 55.2 cm. The Jules Bache Collection, 1949, 49.7.42. © 2000–2023 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Attributed to Juan de Pareja (Spanish, Antequera 1606–1670 Madrid), Philip IV, 1650. Oil on canvas, 76 × 62 cm, Santa Maria Maggiore, Rome.

Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, Seville 1599–1660 Madrid), Innocent X, 1650. Oil on canvas, 68.6 × 55.2 cm. The Duke of Wellington, Apsley House.

Possibly by Velázquez (Spanish, Seville 1599–1660 Madrid), Portrait of a Man, ca. 1650. Oil on canvas, 69.2 x 56.5 cm. Marquand Collection, Gift of Henry G. Marquand, 1889, 89.15.29. © 2000–2023 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, Seville 1599–1660 Madrid), Camillo Astalli, 1650. Oil on canvas, 61 × 48.5 cm. The Hispanic Society of America, New York.

Attributed to Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, Seville 1599–1660 Madrid), Juan de Córdoba, ca. 1650. Oil on canvas, 67 × 50 cm. Capitoline Museums, Rome.

Velázquez (Diego Rodríguez de Silva y Velázquez) (Spanish, Seville 1599–1660 Madrid), Young Woman, ca. 1650. Oil on canvas, 65 × 51 cm. Private collection, VP.058.

Juan de Pareja (Spanish, Antequera 1606–1670 Madrid), José Ratés, ca. 1664. Oil on canvas, 116.9 × 97.8 cm. Museo de Bellas Artes de València.

Tazza, Portuguese, second half 17th century. Silver, 11.7 × 27.9 cm. Rogers Fund, 1912; 12.124.15. © 2000–2023 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Jarro de Pico, Possibly by Hernando Solis, Spanish, Valladolid, late 16th century. Silver, parcel-gilt. Overall (confirmed): max ht. 7 5/8; ht. from upper edge of body: 19.4; 16 x 21.3 x 10.6 cm, 0.9474kg. Purchase, Friends of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts Gifts, in memory of Olga Raggio, 2009; 2009.227. © 2000–2023 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

A luxury utensil of near-mythic status, the jarro de pico was the quintessential domestic object of the so-called golden age of Hispanic silver. These ornately beaked ewers, intended for hand washing at the tables of the wealthy, typically meld elements of Renaissance style with the geometrically conceived forms of the Philip II and Philip III periods, or the last half of the sixteenth and early part of the seventeenth century. In the jarro de pico the austerity of the ewer’s turned body is offset by the powerfully modeled detail on the spout, which is often reminiscent of the grotesque designs popular in Renaissance Italy. The sculptural vigor of this ewer’s spout, in the form of a bearded man with a foliate crown and pointed animal’s ears, contrasts with the sleekly functional, almost ergonomic form of the flamboyant handle, which features a spiky curve at its base and an unusually prominent thumb scroll that extends its height. The purity of the body is accented only by gilded horizontal bands and moldings.

Inside the foot of this jarro de pico are a mark bearing the arms of the city of Valladolid and a partial mark that has been tentatively identified as that of the silversmith Hernando Solis.

Dish (salver or basin), Spanish, early 17th century. Silver gilt, enamel. Diameter: 66 cm. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917; 17.190.570. © 2000–2023 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Plate, 1470–1490, probably Manises, Valencia, Spain.Tin-glazed earthenware,7.5 x 43.2 cm.The Cloisters Collection, 1956; 56.171.104. © 2000–2023 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Dish, 1420–1430, probably Manises, Valencia, Spain. Tin-glazed earthenware, 6.7 x 45.1 cm. The Cloisters Collection, 1956; 56.171.128© 2000–2023 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Dish, late 15th century, probably Manises, Valencia, Spain. Tin-glazed earthenware, 6 x 47.5 cm. The Cloisters Collection, 1956; 56.171.141 © 2000–2023 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F77%2F71%2F119589%2F128580684_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F98%2F02%2F119589%2F122212744_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F57%2F55%2F119589%2F94038030_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F51%2F119589%2F93829216_o.jpg)