Gregg Baker Asian Art at TEFAF Maastrich 2017

School of Hasegawa, A six-fold screen depicting Kakimoto no Hitamaro gazing at the moon and sitting on the shore of Kei no Matsubara, Japan, Momoyama-Edo period, 17th century. Ink and colour on paper and gold leaf, 172 x 377 cm © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (662-710) was a Japanese waka poet and aristocrat of the late Asuka period (538 to 710). He was the most prominent of the poets included in the Manyōshū (Poetry Collection of Ten Thousands Leaves) compiled in the middle of the eight century, the earliest surviving anthology of Japanese poems.

Hitomaro was born to the Kakinomoto clan, an aristocratic court family responsible for preserving and reciting the oral history of Japan to the court. Having grown up under the artistic influence of previous generations Hitomaro excelled as a poet. He is believed to have begun working at the court in 680 under Emperor Temmu (631-686) and continued to serve under Empress Jitō (645-703) when it is generally considered that he flourished. He also spent time in government service in several places away from the capital giving him the opportunity to compose poetry praising the Japanese landscape.

One of the Sanjyurokkasen (thirty-six immortal poets) Hitomaro has always been held in high regard with continuing fame until the present day. Being the most famous of all the 36 poets, images depicting him were often produced as an inspiration for other aspiring poets. This iconic image of a bearded man leaning on an armrest looking up to the right became a standard representation. This screen depicts the poet in his classic pose contemplating the moon from the shores of Kei no Matsubara; a scenic landscape on Awaji Island which gained great fame after Hitomaru’s poem:

Kehi no umi

niwa yoku arashi

karikono no

midarete izimiyu

ama no tsuribune

The sea at Kei

must be a good place to harvest.

For like reeds cut free

they float in confused array-

those boats of the fishermen

A scroll dating to the 13h century attributed to Fujiwara Nōbuzane (1162-1241) depicting Hitomaro in his classic pose can be found in the collection of Kyoto National Museum (Ref. no. A kō 14)

Yuichi Inoue (1916-Tokyo-1985), Shoku (Belonging), Japan, 1976. Ink on paper, 120 x 221.5 cm. Seal 'Yūichi' © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Provenance: Acquired by the previous owner from Japan Art, Frankfurt, Germany

Literature: YU-ICHI, Catalogue Raisonne, vol. 2, UNAC Tokyo, no. 76015

A standing figure of Amida Buddha, Japan, Heian-Kamakura Period, 12th century. Wood and gilt lacquer. Height 88.50 cm © Gregg Baker Asian Art

The figure is standing on a lotus base, the hands in an-i-in mudra and the eyes inset with crystal. The head is adorned with a crystal representing the byakugō (white spiraling hair) on the forehead and the nikkei-shu (red jewel on the protrusion on top of the Buddha's head).

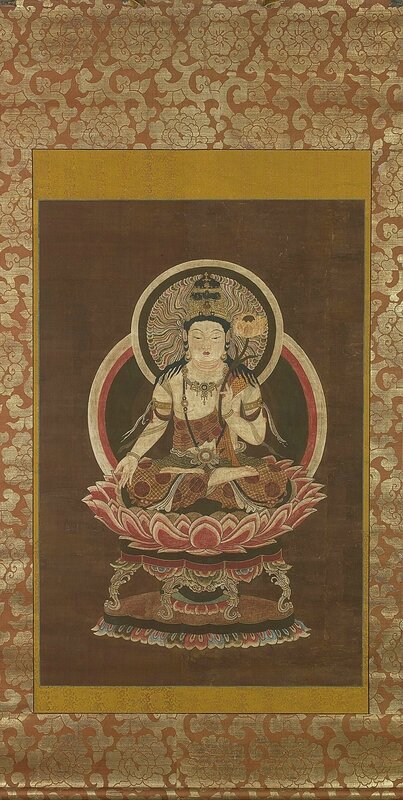

A silk kakemono (hanging scroll), Japan, Muromachi period, 16th century. Ink and colour on silk, 203 x 100 cm © Gregg Baker Asian Art

This kakemono is painted in ink and colour with a Shō Kannon seated in kekka fuza (lotus position) on a lotus pedestal raised on a four-legged dais, holding a renge (red lotus) in her left hand. The right hand is in segan-in mudra, the gesture of dispensing favours for the well-being of the world. The head is adorned with kebutsu crown at the base of a tall top-knot and she is wearing an elaborately decorated necklace and armlets.

Tadasuke Kuwayama (Japan, 1935), Tadasky, 1965. Oil on canvas, 142.5 x 142.5 cm. Signed on the reverse © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Provenance: Feigen - Palmer Gallery, Los Angeles

A figure of Amida Buddha, Japan, 15th century. Gilt-wood. Heigt 50 cm © Gregg Baker Asian Art

A gilt-wood figure of Amida Buddha seated in kekka fuza (lotus position) the hands in jō-in (meditation mudra). The head is adorned with crystals representing the byakugō (white spiralling hair) on the forehead and the nikkei-shu (red jewel on the protrusion on top of the Buddha's head).

This type of jō-in mudra is frequently used in Japanese Esotericism, especially in statues of the co-called Esoteric Amida. This particular one is characterized by circles formed with the thumbs and indexes and it stands for a specific rank in the Amida hierarchy.

The symbolism of the jō-in mudra is closely associated with the concept of complete absorption of thought by intense contemplation of a single object of meditation, in such a way that the bonds relating to the mental faculties to so-called ‘real phenomena’ are broken and the worshiper is thus enabled to identify himself with the Supreme Unity through a sort of super-intellectual raptus. In the jō-in the position of the hands is that of the adepts of yogic contemplation. Thus the jō-in symbolises specifically zenjō (ecstatic thought) for it is the gesture which indicates the suppression of all spiritual disquiet in order to arrive finally at the complete concentration on the truth.

The position of the hands in the mudra of concentration derives, in accordance with the tradition, from the attitude which the historical Buddha assumed when he devoted himself to final meditation under the Bodhi tree. This id the attitude he was found in when the demon armies of Mara attacked him. He was to alter it only when he called the earth to witness at the moment of his triumph over the demons. Consequently the position symbolises specifically the supreme mediation of the historical Buddha but also the Buddhist qualities of tranquillity, impassivity and superiority.

The circle formed by the fingers in this figure means the perfection of the Law because the circle is the perfect form. The formation of the two circles by the two hands representing respectively the world of the Buddhas (right hand) and that of Sentient Beings (left hand) indicates that the Law conceived by the Buddha is sustained by Sentient Beings who integrate themselves into it completely. The two juxtaposed circular shapes represent the accomplishment and the perfection of Buddhist Law in its relationship to all Beings. The right-hand circle symbolises the divine law of the Buddha, the left-hand circle, the human law of the Buddha. Side by side, the circles symbolise the harmony of the two worlds, that of Sentient Beings and that of the Buddha. The fingers are entwined; those of the left hand represent the five elements of the world of Beings and those of the right hand the five elements of the world of the Buddhas.

The two circles of this type of jō-in mudra also stand for the two aspects of cosmic unity; the Diamond World and the Matrix World. These circles are separated from each other because they are formed by two different hands. The circles are joined in this mudra to constitute a single unity which symbolises, by the form of their juxtaposition, the double aspect of a single world and the concept of All-One, the basic principle of Esotericism.

Belief in Amida as Lord of the Western Paradise rose in popularity during the late 10th century. Based primarily on the concept of salvation through faith, it was not only a religion which appealed to a broad range of people, but also a direct assertion of piety against the dogmatic and esoteric ritual of the more traditional Tendai and Shingon sects. In Amida’s Western Paradise the faithful are reborn, to progress through various stages of increasing awareness until finally achieving complete enlightenment.

Images of Amida, lord of the Western Paradise, are known in Japan from as early as the seventh century. Until the eleventh century the deity was most frequently portrayed in a gesture of teaching and was worshipped primarily in memorial rituals for the deceased. However, in the last two centuries of the Heian period worshippers started to concentrate more on the Teachings Essential for Rebirth written by the Tendai monk Genshin (942-1017). The teachings describe the horrors of Buddhist hell and the glories of the Western Paradise that can be attained through nembutsu, meditation on Amida or the recitation of the deity’s name.

Despite the apparent absence of formal variations in the images themselves, during the latter part of the Heian period important changes did occur in the nature

of the rituals held in front of the Lord of the Western Paradise. By the twelfth century Image Halls dedicated to Amida were the ritual centres of most complexes. The function of memorial services was expanded so they benefited not only the dead, but also the living. Even rituals with no historical connection to the deity, such as the important services at the start of the New Year, were held there. Of particular significance were the novel ritual practices that were held to guarantee one’s rebirth in Amida’s Western Paradise. Some, such as the re-enactment of the descent of Amida, or the passing of one’s last moments before death clutching a cord attached to the hands of the deity, were entirely new whilst others, including the use of halls dedicated to Amida as temporary places of interment, reflected the fusion of more ancient practices with doctrines of rebirth.

Taihaku Taihaku (1893-Japan-1961), Kunpū (warm breeze), Japan, 1934. aper screens, ink and mineral colours on silver ground, 176.5 x 180 cm (each). Signed 'Shōwa kyūki Taihakusei' (Shōwa 9th year*. Made by Taihaku) © Gregg Baker Asian Art

A pair of two-fold paper screens painted in ink and colour on a silver ground with sagi (egrets) perched on the branches of a yanagi (willow) tree. The light green young leaves are rendered in moriage (raised design) and symbolise early spring. Numerous sakura (cherry blossom) petals are scattered in the air and on the river bank where small tampopo (dandelion) appear in full bloom.

Literature: 1934 Inten, Japan Art Institute Exhibition, exh. cat., p. 735, pl. 37

Suda Kokuta (1906-1990), Untitled, Japan, 1963. Mixed media on canvas, 130 x 97 cm. Signed at the front and on the reverse © Gregg Baker Asian Art

Provenance: Private collection, Osaka, Japan

Gregg Baker Asian Art at TEFAF Maastrich 2017. Stand 260.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F94%2F98%2F119589%2F128936844_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F10%2F21%2F119589%2F128720387_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F66%2F59%2F119589%2F128562333_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F10%2F39%2F119589%2F127811495_o.jpg)