La scène de l'art contemporain italien

Italy has become the basket case of Western Europe. So everybody says. This winter the government, chronically geriatric, fell for the umpteenth time. Decades of festering indecision caused rotting garbage to pile up in the streets of Naples.

But then there’s the contemporary art scene.

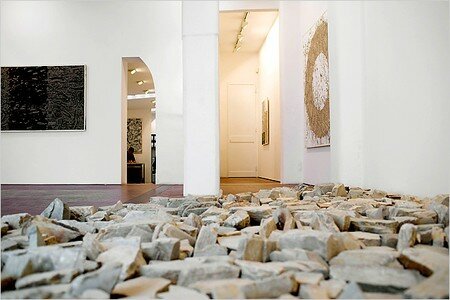

Works by Richard Long at the Lorcan O'Neill Gallery in Rome. (Photo: Marco Di Lauro for The New York Times)

A museum is under construction in Rome, nicknamed Maxxi, designed by Zaha Hadid. A museum opened in Bologna called Mambo. The Prada Foundation bought an exhibition space in the south of Milan; Rem Koolhaas will be that architect. And in the north of Milan there’s Hangar Bicocca, devoted to gigantic installations; Anselm Kiefer’s, an awesome series of towers, has become a pilgrimage site.

In Naples, Madre, a contemporary museum, has a new place. So does the Maramotti family’s art collection.

More is happening in Turin. And Venice has recently turned its customs house over to the French billionaire François Pinault, to show off his collection.

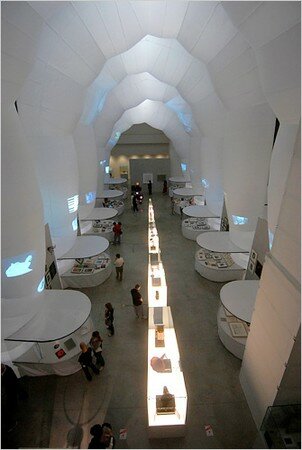

The inaugural exhibition, “Vertigo,” at Mambo in Bologna. (Photo: Chris Warde-Jones for The New York Times)

“Foreigners feel free to make fun of Italy and complain that it’s creaky and corrupt,” said Lorcan O’Neill, a dealer who runs one of the best high-end galleries in town. “For whatever reason, they think it’s charming to insult Italians, never mind that then they go off and buy Prada, eat Italian food and covet Ferraris.” But, he adds, the state still thinks of culture in terms of antiquities, so that’s where the money goes.

The dealer Lorcan O’Neill at his gallery in Rome. (Photo: Marco Di Lauro for The New York Times)

“ “It’s medieval,” the veteran curator Germano Celant said. “All these different villages, city against city, museum against museum — every institution is a one-person project; otherwise nothing happens. There’s no structure, no official culture of expertise.”

Talk about accumulating a modern art collection out of the Venice Biennale — a ready-made source that could have produced a first-class museum — typically came to nothing.

Works by Christopher Wool and Rosemarie Trockel at the Collezione Maramotti. (Photo: Collezione Maramotti)

So private collectors have been left to pick up the slack, for which they’re not really suited. The Italian tax system further burdens them.

Lia Rumma opened a gallery in Naples in 1971, then a second one in Milan 18 years later. She showed Minimalism and Conceptualism when they were nearly unknown here. She nurtured a coterie of young collectors.

“But the market can’t substitute for what really sustains artists, meaning museums, public support and recognition,” she said.

A work by Anselm Kiefer in the Maramotti collection in Reggio Emilia. (Photo: Collezione Maramotti)

In Turin, Patrizia Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, oversees a foundation that has staged a variety of world-class shows. “When I started to collect and visited Germany and London,” she said, “I was shocked to see contemporary Italian artists who were nowhere to be found in Italy. The focus here on antiquity is a way not to be involved more in this moment. But I think things are changing.”

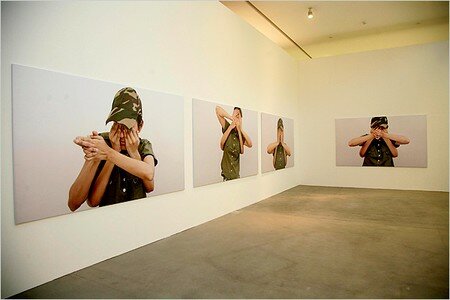

Works by Shilpa Gupta at the Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin. (Photo: Courtesy of Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo, Turin)

They clearly have changed in Turin. The Castello di Rivoli Museum of Contemporary Art now totals maybe 300 works, mostly large installations. Lothar Baumgarten has painted the walls of one room an electric blue and added bird feathers. Sol LeWitt did murals in another room. About 100,000 people visit each year.

“It’s only recently that people in Italy have begun to recognize contemporary art as a cultural value, which other countries use, for economic purposes,” Marcel Beccaria, the curator, said. “Italians have been slow to see there’s a whole economic world out there that rotates around it.”

The Castello di Rivoli Museum of Contemporary Art in Turin. (Photo: Courtesy of the Castello di Rivoli Museum of Contemporary Art)

But Turin is one case, Rome another. Pepi Marchetti Franchi, who manages Larry Gagosian’s new gallery here, said of Mr. Gagosian: “When he first saw Rome long ago, he fell in love with the city, and now he can afford to be extravagant, and he thinks artists he’s interested in will feel the same way about exhibiting here. It’s not for the market. There hardly is any market.”

Pepi Marchetti Franchi of the new Gagosian Gallery in Rome. (Photo: Marco Di Lauro for The New York Times)

Where Rome ends up will depend partly on Maxxi, the state’s modern art museum. A building is under construction. Anna Mattirolo, who has worked in the government arts administration for years, directs it. She said it had been tricky, over the years, getting Culture Ministry bureaucrats to approve contemporary acquisitions. But it has gotten better, she said.

Anna Mattirolo of the Maxxi Museum. (Photo: Marco Di Lauro for The New York Times)

“It’s our culture,” Ms. Mattirolo said. “There’s no point in fighting it. It’s impossible to say what will happen. All I know is that if we call great international artists and ask them to do exhibitions, they will come.”

She added, “This is Italy,” and shrugged.

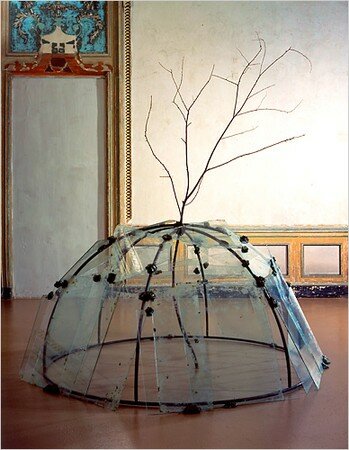

A work by Mario Merz at a gallery in Turin (Photo: Courtesy of Castello di Rivoli Museo d'Arte Contemporanea, Turin)

Lire l'article "Twombly in the Land of Michelangelo" de Michael Kimmelman http://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/16/arts/design/16kimm.html?ex=1363320000&en=66cef571c31d037b&ei=5088&partner=rssnyt&emc=rss

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240429%2Fob_94d73d_artofthe-2.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240429%2Fob_a32180_438086347-1659660838137262-66806538687.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240429%2Fob_5853a1_440937185-1660184551418224-14760604465.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240428%2Fob_096a92_telechargement-10.jpg)