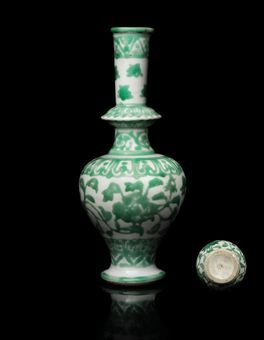

An exceptionally rare green enamel-decorated holy water bottle. Ming dynasty, early 15th century

An exceptionally rare green enamel-decorated holy water bottle. Ming dynasty, early 15th century. photo Christie's Ltd 2010

The high-shouldered body decorated with an undulating peony scroll set between lappet borders below a band of classic scroll at the base of the neck separated by a raised flange decorated with overlapping leaf tips from detached blossoms on the upper neck, all in a soft apple-green enamel and reserved on a white ground - 9 in. (22.8 cm.) high Est. £100,000 - £150,000 ($147,000 - $220,500)

Provenance: Christie's New York, 27 November 1991, lot 338.

Bluett & Sons, London, 30 November 1991.

The property of an English collector.

Notes: Not only is this remarkable vessel a rare example of this form in the early 15th century, it is also an exceptionally rare example of the use of overglaze green enamel to decorate Jingdezhen porcelain at this early date. Indeed, when this flask was sold in Christie's New York rooms in November 1991, it was conservatively dated to the 16th century, since, although the style of the decoration appeared to date to the early 15th century, there were, at that time, no known examples of this decorative technique from the early 15th century. In 1984 a dish with iron red enamel ground and green enamel dragon decoration, applied to the biscuit, and another dish with yellow enamel ground and green enamel dragon decoration, applied to the biscuit, had been excavated at Zhushan, Jingdezhen, from the Yongle strata (illustrated in Imperial Hongwu and Yongle Porcelain excavated at Jingdezhen, Chang Foundation, Taipei, 1996, pp. 318-9, no. 129, and pp. 320-1, no. 130, respectively). However in 1991 no example of a Yongle porcelain vessel decorated in green overglaze enamel had yet been excavated.

Only a few years later, however, new information came to light which allowed confident dating of the current vessel to the early 15th century. In 1994 a stand (fig. 1) with decoration of lingzhi scrolls and a petal band around foot, all executed in overglaze green enamel, was excavated from the Yongle stratum at Dongmentou, Zhushan, Jingdezhen (illustrated in Imperial Hongwu and Yongle Porcelain excavated at Jingdezhen, op.cit., pp. 202-3, no. 70). The stand with green enamel decoration was found together with a zhadou, spittoon, also decorated solely in green enamel. The colour and texture of the green enamel on the stand is wholly comparable with that on the current flask, as is the style of decoration.

Although porcelain bottles of this shape are known from the Qianlong reign, decorated in overglaze iron red enamel or underglaze blue and overglaze enamels in doucai style, Ming dynasty Yongle examples are extremely rare. However, blue and white porcelain vessels with flanges on their necks were being made at Jingdezhen as early as the Yuan dynasty. The neck of such a bottle was excavated from the Yuan stratum at Luomaqiao, Jingdezhen, and included in the exhibition Ceramic Finds from Jingdezhen Kilns, Fung Ping Shan Museum, University of Hong Kong, 1992, no. 150, while two blue and white bottles on stands, preserved in the Qingyang City Cultural Bureau, Anhui province, are illustrated by Zhu Yuping, Yuandai qinghua ci, Wenhua chubanshe, Shanghai, 2000, p. 142, no. 6-19. A Yuan dynasty bottle with flanged neck and pale bluish glaze in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing is illustrated in Zhongguo wenwu jinghua daquan - Taoci juan, Taipei, 1993, p. 355, no. 623, where its use in Tibetan Buddhism is noted. A white glazed vessel of this form was also excavated from the Yuan dynasty stratum at the Dehua kilns in Fujian province (illustrated in Dehua Wares, Fung Ping Shan Museum, University of Hong Kong, 1990, p. 109, no. 94).

A Yongle bottle of this form with a celadon glaze imitating Longquan wares, was excavated from the site of the imperial kilns at Zhushan, Jingdezhen in 1982 (illustrated in Imperial Hongwu and Yongle Porcelain excavated at Jingdezhen, Chang Foundation, Taipei, 1996, pp. 302-3, no. 121). The Yongle examples of this form have a more prominent foot than their Yuan counterparts, and the Yongle vessels are also of more slender and elegant proportions.

Bottles or flasks of this type, which almost certainly developed from a metal proto-type, are often referred to as a 'pure water' or 'holy water' bottles, although they are more properly called kamandalu, which are used to contain holy water, called amrta, although it is sometimes referred to in English as nectar or ambrosia. It is particularly associated with the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara (Guanyin). This bottle form relates to the kendi and the kundika, having the distinctive flange on the neck, but is differentiated from the kendi and kundika by having no spout on the shoulder. The bottle most closely accords with kundika such as the Ding ware examples excavated from the Jingzhi Temple pagoda (dated AD 977) and the Jingzhongyuan Temple pagoda (dated AD 995) in Dingzhou, Hebei province (see Idemitsu Museum of Arts, Treasures from the Underground Palaces - Excavated from Northern Song Pagodas, Dingzhou, Hebei Province, China, Tokyo, 1997, nos. 57-58 and 87). The kundika with shoulder spout is also often referred to as a pure or holy water flask or sprinkler, and both vessels are associated with Buddhism. The bottle has a slightly wider mouth than that seen on the kundika, and the flange is positioned lower on the neck.

In sculpted or painted images of the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara it is noticeable that, from the Tang dynasty onwards, the Bodhisattva holds the vessel by the neck, using the flange to suspend it between two fingers of her right hand. Such a bottle can be seen held between the fingers of a Tang dynasty sandstone eleven-headed Avalokitesvara from the Baoqing Temple, Xi'an, Shaanxi province, now in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, dated to c. 703, (illustrated in China - Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2004, p. 301, no. 193). A similar flanged bottle is held in the right hand of a beautiful, Yongle marked, gilt bronze seated figure of Avalokitesvara in the Rietberg Museum (illustrated in On the Path to Enlightenment - The Berti Aschmann Foundation of Tibetan Art at the Museum Rietberg, Zürich, Zürich, 1995, pp. 98-9, no. 52). Unusually this latter figure holds the flask upside-down because the right hand is in the varada mudra (gift bestowing hand gesture); nevertheless the flange on the neck of the bottle can clearly be seen.

As mentioned above, bottles of this form appear to have been made in greater numbers during the Qianlong reign, and several have been preserved. In discussion of a Qianlong iron red decorated flask of this type, the late Professor Wang Qingzheng, noted that this type of Qing dynasty bottle was called a zang cao ping, Tibetan herb bottle or gan lu ping, sweet dew bottle in Chinese (see Wang Qingzheng (ed.) in Dictionary of Chinese Ceramics, Singapore, 2002, p. 47, lower right). In the Qianlong reign it was a specially commissioned imperial gift to Tibetan monks, and according to the Yinliu zhai shuo ci (Description of porcelain from the Studio of Drinking Steams), it was not made after the Qianlong reign because no further Tibetan monks came to court. Professor Wang notes that in the Qing period such bottles were placed in front of Buddhist shrines to hold herbs.

It is likely that Ming dynasty bottles such as the current example were deployed in the same way. The Yongle emperor was a keen patron of Tibetan Buddhism, and invited a number of eminent Tibetan hierarchs to the Chinese court. These visits necessitated additional imperial orders of porcelain vessels, both for use in the rituals conducted by these hierarchs, and to be bestowed upon them as gifts from the emperor. The current flask may well have been commissioned for such an occasion.

Christie's. Fine Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art. 11 May 2010. London, King Street www.christies.com

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_9bd94f_440340918-1658263111610368-58180761217.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_844371_440162278-1658267648276581-39734064969.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240425%2Fob_78c699_440320998-1657454638357882-17494889713.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240421%2Fob_1dddd2_438878301-1654314112005268-81048289869.jpg)