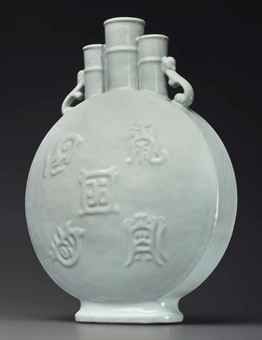

A very rare large guan-type ‘Five Sacred Peaks’ Moon flask, Yongzheng six-character seal mark in underglaze blue and of the per

A very rare large guan-type ‘Five Sacred Peaks’ Moon flask, Yongzheng six-character seal mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1723-1735). Photo Christie's Image Ltd 2013

The sturdily potted body of flattened circular form is finely molded on each convex side with five Daoist emblems, the Five Sacred Peaks, all below the three conjoined cylindrical necks flanked by a pair of scrolled leaf-form handles. The vase is covered overall with an even sea-green glaze suffused with a faint pattern of clear and light brown crackle. 20½ in. (52 cm.) high. Estimate $600,000 – $800,000

Provenance: Collection of Jerry Chu (1921 - 2008) and Lillia Chow (1919 - 1995), acquired before 1960.

PROPERTY FROM THE COLLECTION OF JERRY CHU AND LILLIA ZHOU

Christie's is pleased to offer this remarkable Imperial Yongzheng moonflask from the distinguished collection of Jerry Chu (1921 - 2008) and Lillia Zhou (1919 - 1995). Mr. Chu and Mrs. Zhou were amongst the early generation of Shanghai collectors who had a refined eye and ready access to remarkable works of art.

Mr. Chu was a noted banker and the owner of a successful import/export company on the famous Bund in Shanghai. He was the grandson of Zhang Shou-Yong (1876-1945), a renowned scholar and educator who founded Kwang Hua University in 1925 and served as its first president. Zhang Shou-Yong's personal collection, which included more than 140,000 books and works of art, was highly acclaimed in his own time.

Mrs. Lillia Zhou attended university in Boston and worked at the United Nations until she married Mr. Chu in 1949. Together they carried on their respective family's mutual love of art and collecting, which for them brought both a lifetime of joy and education.

Homage to the Sacred Mountains

Rosemary Scott, International Academic Director, Asian Art This majestic vase is in the flattened circular form that has come to be known as a 'moon flask'. Unlike most other moon flasks, however, it has three distinct necks - a somewhat taller and wider central neck, flanked by two slightly smaller necks. Together they are reminiscent of the Chinese character shan, meaning mountain, and this reference is undoubtedly intentional, since the five symbols moulded on the sides of the flask represent the Five Sacred Mountains of China. The notion of making pilgrimages to mountains is one that has a very long history in China, and is mentioned in the 5th century BC Shujing (Classic of History) in connection with the legendary Emperor Shun, who was traditionally believed to have lived c. 2317-2208 BC. Emperor Shun was reported to have made a pilgrimage every five years to the four mountains that marked the borders of his realm, and offered sacrifices when he reached the summit of each mountain. It is significant that the phrase for pilgrimage in the Chinese language is chaosheng, which is an abbreviation of the phrase chaobai sheng shan, meaning 'to pay ones respects to a sacred mountain'. There appears to have been an accepted grouping of five mountains as early as the Warring States period (475-221 BC). Daoists believed in the concept of sacred peaks connecting heaven and earth, and the cosmology of the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) incorporated the worship of the Five Sacred Peaks (Wu yue ) - symbolizing the four cardinal directions and the centre, as well as other sacred mountains.

This majestic vase is in the flattened circular form that has come to be known as a 'moon flask'. Unlike most other moon flasks, however, it has three distinct necks - a somewhat taller and wider central neck, flanked by two slightly smaller necks. Together they are reminiscent of the Chinese character shan, meaning mountain, and this reference is undoubtedly intentional, since the five symbols moulded on the sides of the flask represent the Five Sacred Mountains of China. The notion of making pilgrimages to mountains is one that has a very long history in China, and is mentioned in the 5th century BC Shujing (Classic of History) in connection with the legendary Emperor Shun, who was traditionally believed to have lived c. 2317-2208 BC. Emperor Shun was reported to have made a pilgrimage every five years to the four mountains that marked the borders of his realm, and offered sacrifices when he reached the summit of each mountain. It is significant that the phrase for pilgrimage in the Chinese language is chaosheng, which is an abbreviation of the phrase chaobai sheng shan, meaning 'to pay ones respects to a sacred mountain'. There appears to have been an accepted grouping of five mountains as early as the Warring States period (475-221 BC). Daoists believed in the concept of sacred peaks connecting heaven and earth, and the cosmology of the Han dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) incorporated the worship of the Five Sacred Peaks (Wu yue ) - symbolizing the four cardinal directions and the centre, as well as other sacred mountains.

The symbols on the sides of the current flask are Daoist talismanic diagrams or insignia known as the 'True Forms of the Five Sacred Mountains', Zhenxing Wuyue. Legend says that the 'true forms' of the Five Sacred Mountains were first given to the Han dynasty Emperor Wudi (r. 140-87 BC) by Xiwangmu (the Queen Mother of the West), and that he had them mounted and encased in precious materials. However, Emperor Wudi's character was not suited to Daoism and Xiwangmu is believed to have caused the scriptures, together with the building in which they were housed, to be burned. Legend also says that the Emperor had given a copy of the 'true forms' to one of his ministers, Dong Zhongshu, although the latter is known for his promotion of Confucianism as an instrument beneficial to governance. All subsequent transmissions of the 'true forms' were believed to be based upon this one. A Map of the Five Sacred Mountains, Wuyue zhenxing tu, is reproduced in the 4th Daozang (Daoist Canon) published between AD 1436 and 1449. This more closely resembles a real map of the mountains, which identifies areas of particular sacred importance within each mountain, and was probably copied from an earlier Daozang. A somewhat different version of the 'true forms' appears carved on a stone tablet dated to AD 1574. A printed version of the 'true forms', showing similar forms to those on the current flask, with a short explanatory inscription, and identifying the mountain that each symbol represents, appears in Luo Wangchang's 1606 Qin Han yin tong, juan 8. By the Wanli reign (1573-1619) of the Ming dynasty these symbols were regularly engraved on stone stelae, and a rubbing from a stone stele dated to 1604 is kept at the Zhong-yue Miao, or Temple of the Central Peak, on Mount Song in Henan province (illustrated in Daoism and the Arts of China, The Art Institute of Chicago, 2000, p. 358, no. 137). This stele has much longer inscriptions accompanying each form, which provide not only the names and locations of the mountains, but also the gods who rule over them. The stele inscriptions also provide references to the peaks in classical literature, the titles conferred on each of the gods in the Tang dynasty Kaiyuan period (AD 713-41), and the changes that were made to those titles during the Song dynasty (AD 960-1279). It is interesting to note that although the printed image of 1606 and the rubbing of 1604 were produced only two years apart, they show the symbols for the individual mountains in different spatial relationships to one another, and both have the symbols placed differently to the symbols seen on the porcelain vessels. Song Shan, representing the centre, is always shown in the centre, but the other mountains are shown at different cardinal points around it. For example, the Southern Mountain Heng Shan is shown top left in the 1606 printed version, bottom left on the 1604 rubbing, and bottom right on the Yongzheng flask.

Daoists believed that, when ascending these mountains, if they wore representations of the 'true forms', or even ingested something on which they were drawn, they would embody the powerful energy of the mountains. This would, in turn, invoke protection from the gods of the mountains, and thus help the wearer to fend off danger from lesser unwelcome spirits. The Ming Jiajing Emperor (1522-66) was an ardent Daoist, and Daoist emblems, predominately the bagua, eight trigrams, decorate many blue and white porcelains of the period, such as the double-gourd vase in the National Palace Museum Collection, Taipei, illustrated inBlue-and-White Ware of the Ming Dynasty, Book V, Hong Kong, 1963, pl. 5. Interestingly, however, the 'true forms' of the Five Sacred Mountains do not appear to have been used on ceramics during his reign and only make their appearance on porcelains as a major decorative motif in the Qing dynasty during the Yongzheng period.

The five mountains are represented in the five cardinal directions of Chinese geomancy - East, West, South, North and Centre. On the flask the symbol on the upper right can be identified with the Eastern Mountain, Tai Shan (in Shangdong province); on the lower right is represented, the Southern Mountain, Heng Shan (in Hunan province); on the lower left, the Western Mountain, Hua Shan (in Shanxi province) is represented; on the upper left, the Northern Mountain Heng Shan (in Shanxi province) is represented; and the central emblem represents the Central Mountain, Song Shan (in Henan province). They represent a balance in cosmic order, and the five also symbolise the Five Phases or Elements: metal, fire, wood, water and earth.

These mountains, however, are not the only sacred mountains in China, nor are they exclusively linked with Daoism. There are Four Sacred Mountains of Buddhism. These are Wutai Shan in Shanxi province, Emei Shan in Sichuan province, Jiu Shan in Anhui province, and Putuo Shan in Zhejiang province. In addition there are Four Sacred Mountains of Daoism, which are Wudang Shan in Hubei, Longhu Shan in Jiangxi, Qiyun Shan in Anhui, and Qingcheng Shan in Sichuan. It is possible that the triple neck of the current vessel, in addition to suggesting the character shan (mountain), may also provide a reference to three legendary mountains. Traditionally mountains were regarded as the dwelling places of immortals and the three most notable of these were known as Peng Lai, Fang Zhang, and Ying Zhou. The Yongzheng Emperor was familiar with the names of these realms of the immortals and, when he expanded the imperial gardens, he included elements which he named in reference to them, such as the pavilion named Pengdao Yaotai, 'The precious pavilion of Pengdao', and also named sections of the garden in reference to Daoist ideals, such asFenglinzhou, 'Islets of the Phoenix and Dragon'.

The choice of the type of glaze used on the current vessel, and on a similar vessel in the Palace Museum, is significant. The vessels' association with pilgrimage to the sacred mountains is clear from the symbols they bear on their sides. They are also exceptionally large and imposing, and the combination suggests that they may have been intended for important ritual use. The application of a glaze that bore a reference to antiquity - to Guan wares of the Southern Song dynasty - would have added further solemnity to the visual impact of the flasks.

The only other example of this similar size, shape, motifs, and Guan-type glaze is a Yongzheng-marked vase in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, illustrated in Gugong bowuyuan cang - Qingdai yuyao ciqi, part I, vol. 2, Beijing 2005, pp. 324-25, no. 148. (Fig. 1) A similar Yongzheng-marked vase, but with a translucent celadon glaze and a background of incised lingzhi and vapour was sold at Christie's Hong Kong, 1 December 2010, lot 3004. (Fig. 2) A Qianlong-marked flask of similar shape and bearing similar moulded motifs was sold at Christie's New York, 3 June 1993, lot 240. While the Yongzheng versions of this form have a solemn dignity, and are without extraneous decoration, the form is also seen amongst more decorative vessels in the Qianlong reign. A smaller vase of this shape with celadon glaze, with large circular panels reserved on either side containing colourful depictions of Daoist figures, is in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing and illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum - 39 - Porcelains with Cloisonne Enamel Decoration and Famille Rose Decoration, Hong Kong, 1999, p. 142, no. 124. The form also appears in flat-backed wall-vases or sedan-chair vases bearing an inscription from the brush of the Qianlong emperor. Interestingly, the National Palace Museum, Taipei, has in its collection a Yongzheng vase with Guan-type glaze, which is formed like a single five-peaked mountain - the central neck being taller and the four additional necks positioned at the cardinal points around it (illustrated in Qing Kang Yong Qian ming ci, Taipei, 1986, no. 65). This five-peak vase does not bear the symbols seen on the current vase, but the reference to the Five Sacred Mountains is clear.

Christie's. FINE CHINESE CERAMICS AND WORKS OF ART. 19 - 20 September 2013. New York, Rockefeller Plaza.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240502%2Fob_bd3c09_telechargement-4.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240502%2Fob_046c62_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240502%2Fob_2a48ba_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240502%2Fob_356701_telechargement.jpg)