Early Nepalese sculpture in focus at Bonhams Indian, Himalayan & Southeast Asian Art sale

NEW YORK, NY.- Bonhams Indian, Himalayan & Southeast Asian Art sale on March 17, part of Asia Week New York, will feature fine and early Nepalese figurative sculptures. Among the highlights is a gilt copper figure of Vajrapani, the Buddha’s protector and guide, from the early 10th century (est. $100,000-150,000). The fluid and joyous sculpture is especially notable for its dark brown patina, acquired through extensive ritual handling. An ethereal 10th/11th century gilt copper figure of the female manifestation of the divine, Devi, will also be offered (est. $80,000-120,000). Both sculptures come from the same distinguished collection.

Edward Wilkinson, Bonhams senior consultant and specialist for the sale commented, “These early Nepalese bronzes are remarkable. There’s very little Nepalese material from this period available and to offer these fine examples directly from a Private US Collection makes them all the more extraordinary. Nepalese sculpture was long-regarded as the pinnacle of Southeast Asian art and the market is currently rediscovering this rich tradition.”

A gilt copper figure of Vajrapani, Nepal, circa 10th century. Estimate US$ 100,000 - 150,000 (€73,000 - 110,000). Photo: Courtesy of Bonhams

In the aspect of Nilambaradhara, wearing eight races ofnagas about his youthful body and a tiger skin over adhoti draped across his thighs, he dances upon a pair of corpses on a lotus platform, with his right hand raised holding the vajra and the left raised in the threatening gesture of tarjani mudra, with a diadem of matted hair, round staring eyes and open mouth baring fangs. 8 1/2 in. (21.5 cm) high

The fluid movement of the figure in a ferocious, yet joyous pose is a tour de force of Himalayan sculpture. Its importance is further accentuated by the smooth dark brown patina established from extensive ritual handling. Close comparisons can been seen in other powerful deities, such as the 9th century Vajrapurusha in the Norton Simon Museum (see Pal, Art of the Himalayas and China, Pasadena, 2003, p. 74, no. 46) and the 10th century Padmataka in the Jokhang Palace, Lhasa (von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculpture in Tibet, Hong Kong, 1981, p. 473, no. 147B, 149A). A more conventional posture of a 10th century 'Angry God' in a private collection with the missing attribute shares similar modeling of the body and adornments, see Pal,Himalayas: An Aesthetic Adventure, Chicago, 2003, p. 33, no. 9.

As noted by Watt, Vajrapani Nilambharadhara is strongly associated with the Sakya tradition as a protector deity, and was also revered by the Kadampa Buddhists (see Linrothe & Watt, Demonic Divine, New York, 2004, p. 226-7). Tingley has argued in reference to the present lot that because Nilambaradhara Vajarapani was important in Tibetan Buddhism during the 10th and 11th centuries, but not in Nepal, this piece may have been produced by a Newari artist for a Tibetan patron (see Tingely Celestial Realms, Sacramento, 2012, p. 42). She further notes that it may have been produced during a time when the iconography of Nilambaradhara was still influx, predating later examples where he stands in alidhasana, rather than dances (ibid., p. 42).

Pal comments, "Normally, in the early art of Nepal he is seen as a placid bodhisattva along with Avalokitesvara and Maitreya. This spirited and expressive bronze may well be the earliest known representation of his angry manifestation in Himalayan and Indian Buddhist art" (Pal,Art of the Himalayas, New York, 1991, p. 45).

Published: Pal, Nepal; Where Gods Are Young, Asia House Gallery exhibition catalogue, New York, 1975, no. 25

von Schroeder, Indo-Tibetan Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1981, no. 109B

Slusser, Nepal Mandala, vol. 2, 1982, pl. 465

Reynolds and Heller, The Newark Museum Tibetan Collection: Sculpture and Painting, Newark, 1986, fig. 2, p. 167

Pal, Art of the Himalayas: Treasures from Nepal and Tibet, New York, 1991, no. 9

Pal, Ars de L'Himalaya, Idoles du Nepal et du Tibet, Paris, 1996, p. 53, no. 9

Carlton Rochell, Ltd, Pantheon of the Gods, New York, 2007, no. 31

Nancy Tingley, Celestial Realms, Sacramento, 2012, no. 4, pp.42-3

Exhibited: Nepal; Where Gods Are Young, Asia House Gallery, New York, 1975.

Art of the Himalayas: Treasures from Nepal and Tibet, January 1992 - October 1993, cat. no. 81, Newark Museum; Portland Art Museum; Phoenix Art Museum; Pittsburgh, The Helen and Clay Frick Foundation; Richmond, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts; Pasadena, Pacific Asia Museum and Tampa Museum of Art.

Celestial Realms, Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, 2012

Provenance: Zimmerman Family Collection, 1960s-2007

Carlton Rochell Ltd, New York, 2007

Private U.S. Collection

A gilt copper figure of Devi, Nepal, circa 10th century. Estimate US$ 80,000 - 120,000 (€58,000 - 88,000). Photo: Courtesy of Bonhams

The sublime goddess stands with the left knee slightly flexed, shifting her weight to the right with perfect poise on a flattened lotus platform, she wears a barely detectable diaphanous sash over her left breast falling to a curving pleated band down the left side, the lower garment is drawn tightly over her hips and thighs and is incised with horizontal bands of repeating floral motifs, she is adorned with matching necklace, jeweled crown and bands high on the upper arms, she holds a gem or seed in her right hand as she opens the palm in the gesture of charity, the left hand in kartaka mudra, her face with well-worn delicate features framed by a nimbus with a raised band of pearls and incised flames. 8 5/16 in. (21.1 cm) high

As all Lakshmi, Parvati and Tara are known to hold the lotus seed, the name Devi is an encompassing name that refers to The Goddess regardless of her many forms. Variously named during her long published history, the present lot has most commonly been identified as Devi on the basis of the ambiguity of her lone attribute, the lotus seed or gem and the missing attributed in her left.

Pal suggests she is Tara and a "direct descendant of the 7th century Eilenberg Tara", now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see Pal, Nepal; Where Gods Are Young, New York, 1975, no. 37, p. 54). Whereas a more conservative approach naming her Devi, has been applied more recently to the entire known group of closely related examples in the Cleveland Art Museum and British Museum published in von Schroeder, Indo-Tibetan Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1981, nos. 75G and 81F, and several others in the Jokhang Palace in Lhasa (see von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculpture in Tibet, Vol. I, Hong Kong, 2000, pp. 445, 479-481, nos. 138E-G, 150C-H). Commenting on the latter, von Schroeder discusses the issues regarding the iconography of standing female deities in this period. Lastly, compare the proportions and crown with a black stone stele of Devi, sold Sotheby's, New York, 21 March 21 2002, lot 45 - noteworthy is the long sinuous stem of a lotus flower she holds in her left hand.

Pal suggests she is Tara and a "direct descendant of the 7th century Eilenberg Tara", now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (see Pal, Nepal; Where Gods Are Young, New York, 1975, no. 37, p. 54). Whereas a more conservative approach naming her Devi, has been applied more recently to the entire known group of closely related examples in the Cleveland Art Museum and British Museum published in von Schroeder, Indo-Tibetan Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1981, nos. 75G and 81F, and several others in the Jokhang Palace in Lhasa (see von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculpture in Tibet, Vol. I, Hong Kong, 2000, pp. 445, 479-481, nos. 138E-G, 150C-H). Commenting on the latter, von Schroeder discusses the issues regarding the iconography of standing female deities in this period. Lastly, compare the proportions and crown with a black stone stele of Devi, sold Sotheby's, New York, 21 March 21 2002, lot 45 - noteworthy is the long sinuous stem of a lotus flower she holds in her left hand.

In the absence of consistent inscriptions, the dating of Licchavi and Transitional Period bronzes is difficult to establish on stylistic grounds alone. The Cleveland Devi cited above (1983.153) provides the most favorable comparison in the modeling of the form, treatment of the jewelry, and pleated sash, and is ascribed to circa 8th century. Meanwhile, the present lot has been more recently been given an early 11th century date. See Tingley in Celestial Realms, Sacramento, 2012, no. 6, pp. 46-7 for full discussion.

The remarkable degree of wear from sustained ritual handing is a common trait of Nepalese sculpture that is directly handled during worship. With the features almost worn smooth, her divine face has taken on a further etherial quality amplifying her divine qualities.

Published: Pratapaditya Pal, Nepal; Where Gods Are Young, Asia House Gallery exhibition catalogue, New York, 1975, no. 37, p. 54.

Ulrich von Schroeder, Indo-Tibetan Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1981, no. 76F, p. 309.

Nancy Tingley, Celestial Realms, Sacramento, 2012, no. 6, pp. 46-7

Exhibited: Nepal; Where Gods Are Young, Asia House Gallery exhibition catalogue, New York, 1975

Celestial Realms, Crocker Art Museum, Sacramento, 2012

Provenance: William Wolff, New York before 1975

Private Collection, New York 1976-2003

Rossi+Rossi, London 2003

Sotheby's, New York, 26 March 2003, lot 32

Private U.S. Collection

Additional Nepalese highlights include a 13th century gilt copper Yogambara (est. $150,000-250,000). This masterful rendering of intertwined bodies, delicately inlaid with jewels, comes from a superb Private American Collection of Himalayan art to be offered in the sale. A 12th century Central Tibetan copper alloy Avalokiteshvara from the same collection will also be available (est. $300,000-500,000), as will a Tibetan Thirty-Two-Deity Guhyasamaja Mandala, circa 1520-1530 (est. $400,000-600,000).

A gilt copper figure of Yogambara, Nepal, circa 13th century. Estimate US$ 150,000 - 250,000 (€110,000 - 180,000). Photo: Courtesy of Bonhams

The three-headed, six-armed god caresses Jnanadakini's breast with one hand, holding the skullcup, arrow (now missing), bow, bell, and thunderbolt scepter (vajra) in arms held with a dancer's poise, Jnanadakini meets Yogambara's gaze as she wraps herself around his torso, both deities' belts are unhooked, their clasps ajar at their backs. 7 in. (18 cm) high

Entwined in a lovers' embrace, Yogambara and Jnanadakini symbolize blissful transcendence, the experiential goal and highest teaching of Esoteric Buddhism.

A casting tour de force, the artist has masterfully rendered the complex iconography of two intertwined bodies, imbuing the figures with a sense of tenderness and calm. The sculpture bears the hallmarks of Nepalese craftsmanship - beautifully gilded copper, jewelry delicately inlaid with gems. The physiognomy is also Nepalese, the features diminutive and finely formed. From at least the 7th century, Newar craftsmen were renowned for their artistic talents, creating sculpture and painting in the Kathmandu Valley and also for patrons in Tibet and China. Many surviving Nepalese works of art were produced by itinerant artists beyond the borders of Nepal. A series of devastating raids in the Kathmandu Valley between the end of the 13th and the middle of the 14th centuries decimated the Valley's wooden architecture, and countless sculptures and paintings as well.1 Thus, Nepalese works of art made for and by Nepalese are rare from the 13th century and earlier.

Remnants of red powder in the crowns of both figures indicate its use in ritual ceremonies long ago. The Tibetan pilgrim Dharmasvamin lived in Nepal between 1226-34 where he witnessed the worship of a celebrated image over the course of several weeks. According to his account, the image was removed from the temple in great pageantry. Offerings including curd, milk, sugar water, and honey were poured over the head of the statue, and then it was washed. The ablutions continued over the course of two weeks. Again accompanied by a great spectacle, the image was returned to its chapel where red pigment was reapplied.2 While we cannot know the precise rituals once associated with this image, the red pigment in the crowns and wear to the gilding suggest that similar rites may have been enacted.

Nearly twenty monasteries in the Kathmandu Valley today house images of Yogambara in the monasteries' agam, or tantric chapel.3 As historian John Locke notes, "Every Newar family has a lineage deity, degu dya (or digu dya), a deity that is worshipped annually by all members of an extended family or lineage. Theoretically all who worship the deity are descended from a common ancestor. Every family attached to a baha[l] has a lineage deity; and, in all but a few cases, the entire sangha of a baha[l] has the same lineage deity...A large number of the sanghasidentify their deity as Yogambara, Cakrasamvara, Vajrayogini, or Vajravarahi."4

Yogambara is a lineage deity associated with Kwa Bahal in Patan, perhaps founded by King Bhaskaradeva in the 11th century.5 Along the first floor of the eastern wing of the bahal is a tantric chapel (agam) which houses an image of Yogambara.6 Worship of the tantric deity is a focal point for ritual devotion in the community, performed by ten monastery elders. Locke mentions daily and monthly ceremonies (puja). "On the day of the full moon the whole group [of 10 elders] first performs a puja to thekwapa-dya [main image of the monastery] ...and after that a puja to Yogambara followed by a feast."7

The liturgy associated with Yogambara can be found in the Chaturpitha Tantra.8 Yogambara's seventy-seven-deity mandala appears in the Vajravali, a text compiled around 1101-1108 at Vikramashila monastery by the Indian Buddhist scholar Abhayakaragupta (1084-1130).9The iconography of this exceptional sculpture is thus rooted in eastern Indian medieval Buddhist culture. A Sanskrit manuscript of the Vajravali, dated nepal samvat 202 (1081 CE) was copied at the Turaharnavarna Mahavihara in Manigalake in Nepal.10 There were many ties between Buddhist centers in eastern India and Nepal as teachers, students, and merchants linked the two regions. The Kathmandu Valley also served as an entrepôt for transmission of Buddhism to Tibet. Tibetan Buddhist Marpa (1012-1097) received Yogambara initiations in Nepal from Paindapa.11 Yogambara subsequently became an important deity in Tibet, introduced by Marpa and Ngog Lotsawa, both of whom spent time in the Kathmandu Valley en route to and from India and Tibet.12

In the 13th century, when this image is likely to have been made, north India was transformed by a series of catastrophic raids that effectively eradicated Buddhism from the region. Monks and others connected with the massive monastic universities ( mahavihara) of north India perished or fled, many finding refuge in Nepal. The Kathmandu Valley Buddhist community was immeasurably enriched by this influx of talent, and manuscripts and small bronzes were brought by these refugees. It is possible that the Newar artist who created this Yogambara and Jnanadakini sculpture was inspired by eastern Indian art. The lotus petal base is not typically Nepalese but does resemble examples from eastern Indian medieval sculpture.13 In its superb casting, lustrous gilding, skillfully inset gems and size, the sculpture may be compared with a c. 13th century Nepalese sculpture of Uma-Maheshvara in a private collection.14

1. Luciano Petech, Mediaeval History of Nepal, Rome, 1958, pp. 102-126.

2. George Roerich, trans., Biography of Dharmasvamin (Chag lo-tsa-ba dpal), Patna, 1959, pp. 6, 54-5.

3. John Locke, Buddhist Monasteries of Nepal, Kathmandu, 1985, pp. 518.

4. ibid., p. 13. See also Dina Bangdel, "Tantra in Nepal" in John Huntington and Dina Bangdel, The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art, Columbus, 2003, pp. 29-35.

5. John Locke, 1985, pp. 517-18; Niels Gutschow,Architecture of the Newars, Serindia, 2011, vol. II, p. 758.

6. ibid., p. 758. A second tantric chapel holds an image of Cakrasamvara-Vajravarahi.

7. John Locke, 1985, p. 38.

8. http://www.himalayanart.org/image.cfm/776.html

9. Raghuvira Chandra and Lokesh Chandra, Tibetan Mandalas (Vajravali and Tantra-Samuccaya), Delhi, 1995. See also D.C. Bhattacharyya, "Abhayakaragupta's Vajravali-nama-mandalopayika" in Tantric and Taoist Studies in Honour of R.A. Stein. Vol. 1, Bruxelles: Institute Belge des Hautes Etudes Chinoises, 1981, and Gudrun Buhnemann and Musahi Tachikawa (eds.)Nispannayogavali: Two Sanskrit Manuscripts from Nepal, Tokyo, 1991.

10. John Locke, 1985, p. 39. According to Locke, Manigalake is the area where Kwa Baha is located, and the name Turaharnavarna may have been an earlier name for the monastery that is also known today as Hiranyavarna, "Golden Temple".

11. John Huntington and Dina Bangdel, 2003, p. 33.

12. Tibetan images of Yogambara can be seen at: http://www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=521

13. N R Ray, K Khandalavala, S Gorakshkar, Eastern Indian Bronzes, New Delhi, 1986, figs. 179, 226-227 and passim. For possible Nepalese antecedents, see Ulrich von Schroeder, Indo-Tibetan Bronzes, Hong Kong, 1981, figs. 79A, 79B, 80C.

14. Published in Jane Casey, Naman Ahuja, and David Weldon, Divine Presence: Arts of India and the Himalayas, Milan, 2003, pp. 114-15. See also a c. 14th century gilt copper sculpture of Yogambara and Jnanadakini in the Hung Foundation, Taipei, published in Hung's Arts Foundation, 30 Antique Bar: 2012, Taipei, 2012, pp. 136-43.

Provenance: Private American Collection

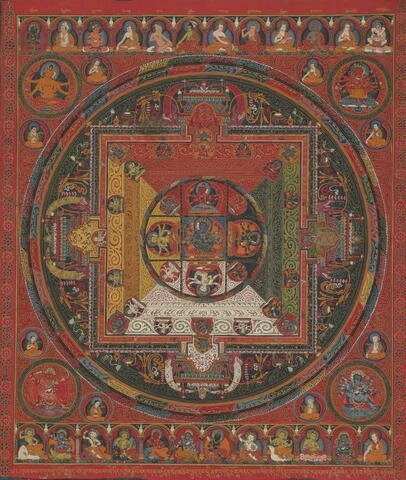

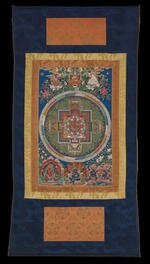

A Thirty-Two-Deity Guhyasamaja Mandala, Tibet, Ngor monastery, circa 1520-1533. Photo: Courtesy of Bonhams

distemper on cloth with original blue cloth mounts and inscribed red lacquered rod, inscribed in gold in the top and bottom margins; the central figure of Guhyasamaja with three faces and six hands with a slightly fierce expression embraces his consort Sparshavajra while seated in vajra posture, the surrounding thirty solitary male and female deities occupy the red, green, white, and yellow mandala palace and include the twelve protective deities that guard the outer corners and gateways, in the corners outside the circle Manjuvajra Guhyasamaja, Lokeshvara Guhyasamaja, Rakta Yamari, Krishna Yamari, flanking these corner protector deities in smaller roundels are Sachen Kunga Nimpo, Grags-pa rgyal-mchan, and other lineage masters identified by inscriptions, the top register contains Vajradhara and the lineage of Indian, Nepali and Tibetan teachers, and the bottom register is Sakya Pandita, Panjarnata Mahakala and the ten gods of the worldly heavens. Image: 20 x 17 1/2 in. (50.7 x 44.3 cm)

The inscription along the bottom margin reads:

དཔལ་ལྡན་གསང་བ་འདུས་པའི་དཀྱིལ་འཁོར་བླ་བརྒྱུད་འདོད་ལྷ་དང་བཅས་པ་འདི་ཉིད། དཀྱིལ་འཁོར་རྒྱ་མཚོའི་རིགས་བདག་འཇམ་དབྱངས་དཀོན་མཆོག་ལྷུན་གྲུབ་པའི་ཐུགས་དགོངས་རྫོགས་པ་དང་།ཕ་མ་སེམས་ཅན་ཐམས་ཅད་ཀྱི་དོན་དུ། དགེ་སློང་ཀུན་དགའ་རྒྱལ་ མཚན་གྱིས་བཞེངས། དགེ་བ་སེམས་ཅན་ཐམས་ཅད་དོན་དུ་བསྔོ་བར་དགེའོ།

This Shri Guhyasamaja mandala, together with the lineage teachers and Desire [Realm] gods, to fulfill the wishes of the Lord of an ocean of mandalas, Jamyang Konchog Lhundrub, and for the benefit of parents and sentient beings was made by Bhikshu Kunga Gyaltsen. May the merit be dedicated to all sentient beings.

Therefore, we understand that the mandala was commissioned by Kunga Sonam, likely to be Jamyang Kunga Sonam (1485-1533) the 22nd Sakya Tridzin, in the fullfilment of the wishes and aspirations of Ngorchen Konchog Lhundrub (1497-1557), the 10th Ngor Khenchen. The two important historical figures overlapped between 1520-1533, providing the secure basis for dating.

Konchok Lhundrub was enthroned as the tenth abbot of Ngor at the age of thirty-eight. He is recorded to have excelled in teaching, debate, and writing, and demonstrated the classic Buddhist qualities of being learned, virtuous, and noble. He had disciples in many distant regions, including Kham, Amdo, U, and Ngari. Konchok Lhundrub did not stay full-time at Ngor, but traveled to Nyangrong, Mu, Nalendra, and various other monasteries to teach. Many powerful families such as the Khon and the Rinpung (rin pungs pa) relied on his instruction.

In authoritative biographies listed on treasuryoflives.com, Konchok Lhundrub held the throne at Ngor for almost twenty-five years, until he passed away in 1557. During that time, he gave the Lamdre teachings thirty-three times, in addition to many other beneficial activities such as commissioning works of art. Jamyang Kunga Sonam, also known as Sakya Lotsāwa Jampai Dorje was enthroned as the twenty-second throne holder of Sakya in 1496. It is recorded that he studied the arts with Zhalu Lotsāwa Rinchen Chokyong (1441-1527) and travel extensively to receive teachings at Ngor, Tsedong, Nalendra, Lingga Dewachen, Reting and other monasteries.

This particular painting depicts a lineage that is called the 'early' or 'old' lineage according to Jamgon Ameshab Kunga Sonam (1597-1660). There are four principal lineages for this form of the meditational deity Guhyasamaja. The first is the lineage of Abhayakaragupta contained in the famous Vajravali text. The second lineage is that of Nyen Lotsawa, no.42 in the Gyu de Kuntu set of mandalas. The third lineage belongs to Marpa Lotsawa and the text is found in the Kagyu Ngag Dzo. The fourth lineage is that of Go Lotsawa Kugpa Lhatse. This mandala painting belongs to the Go Lotsawa Tradition. In the textual literature, farther down in the list of lineage teachers are Sa Lotsawa Jambaiyang Kunga Sonam immediately followed by Yongdzin Konchog Lhundrub. The painting above was commissioned by Kunga Sonam for his student Konchog Lhundrub - both lineage holders for this particular tradition of Akshobhyavajra Guhyasamaja.

The finely detailed Newar scrollwork is larger and more defined through the use of meow pronounced outlining and shading compared with earlier examples of the Beri tradition at Ngor. In the red spandrels, the interlocking roundels are formed with the broad terminus facing each other. Also noteworthy is the graduation in scale of the scrolling elements within the palace, starting with small minor scrolls around the principle figure and climaxing with larger, more open, elements dividing the deities that frame the square. Together with variance in underlying ground colors, this creates a visible dimensional effect of the palace structure.

For a closely related Thirty-Two-Deity Guhyasamaja Mandala of the same scale and period with minor differences in the upper and lower registers in the Navin Kumar Collection, see Huntington and Bangdel, Circle of Bliss, Buddhist Meditational Art, Los Angeles, 2003, p, 443, no. 136. Also compare with a Chakrasamvara mandala in the Rubin Museum of Art, see Linrothe and Watt, Demonic Devine: Himalayan Art and Beyond, New York, 2005, p.199, no. 43. Additionally, compare a Vajrabhairava mandala commissioned by Lhachog Sengge in the Rubin Museum of Art, C2005.16.40 (HAR 65463).

Published: HAR #30510 - http://www.himalayanart.org/image.cfm/30510.html

Provenance: Private American Collection

1. Akshobhyavajra 2. Guhyasamaja 3. Amitabha 4. Amoghasiddhi

5. Vairochana 6. Ratnasambhava 7. Gauri 8. Tara

9. Lochana 10. Mamaki 11. Gandhavajra 12. Rasavajra

13. Rupavajra 14. Shabdavajra 15. Hayagriva 16. Manjushri

17. Niladanda 18. Nivarana Vishkambhin 19. Samantabhadra 20. Mahabala

21. Maitreya 22. Yamanatak 23. Kshitigarbha 24. Achala

25. Vajrapani 26. Akashagarbha 27. Takkiraja 28. Lokeshvara

29. Shumbha 30. Vignantaka 31. Ushnisha Chakravarim 32. Prajnanraka

33. Vajradhara 34. Indrabhuti 35. Jnana Dakini 36. Raja Visukalpa

37. Brahmin Saraha 38. Arya Nagarjuna 39. Aryadeva 40. Shakya Mitra

41. Mahasiddha Nagabodhi 42. Shri Chandrakirti 43. Shisha Vajra 44. Krishnacharin

45. Indra 46. Yama 47. Varuna 48. Yaksha

49. Agni 50. Raksha 51. Vayu Deva 52. Ishana

53. Brahma 54. Bhudevi 55. Panjarnata Mahakala 56. Sakya Pandita

A. Manjuvajra Guhysamaja B. Gomashri C. Go Lotsawa D-E. Avalokita Guhyasamaja

F. Pandita Viryabhadra G. Upa Geser H-I. Krishna Yamari J. Nam Ka'upa

K. Lobpon Sonam Tsemo L-M. Rakta Yamari N. Jetsun Dragpa Gyaltsen O. Sachen Kunga Nyingpo

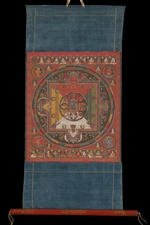

Splendid Tibetan mandalas can be found throughout the sale, including 18th and 19th century pieces with a Chinese-influenced aesthetic. A black ground thangka of Panjaranatha Mahakala from Tibet, circa 1800, will be on offer from a private UK collection (est. $30,000-40,000), while an 18th century Mandala of Chakrasamvara from Central Tibet is best compared with similar examples found in the Palace Museum, Beijing (est. $100,000-150,000).

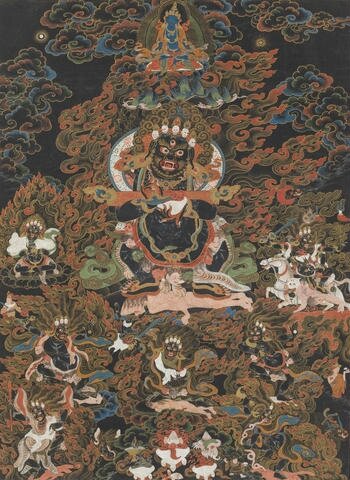

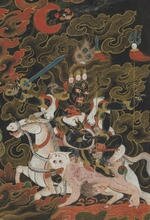

A black ground thangka of Panjaranatha Mahakala, Tibet, circa 1800. Estimate US$ 30,000 - 40,000 (€22,000 - 29,000). Photo: Courtesy of Bonhams.

Distemper on cloth; holding a curved knife and skullcup to the heart with a gandhi stick resting across the forearms, with a very fierce expression and all the customary wrathful ornaments and attire such as the necklace of fifty freshly severed heads, tiger skin lower garment and a long snake as a Brahmin cord, he stands atop a corpse above a dark sun disc surrounded by a mass of flaming fire with three garudas above and a black dog.

At the top of the composition is Buddha Vajradhara (2) and at middle left side is Ekajati (3) and right Shri Devi Dudsolma with four arms and riding a donkey (4), in the lower portion are the Five Karma Activity deities: Kala Rakshasa (5), Putra (6), Kal Rakshasi (7), Bhatra (8) and Singmo (6) and four other small figures depicted in the lower composition. Additionally there is a warrior (A), a dark woman (B) a mantradharin (ngagpa) (C) and a Buddhist monk (bhikshu) (D). These four figures of the outer retinue each represent a thousand figures for each of the four types: a 1000 warriors, a 1000 black women, a 1000 mantradharins, and a 1000 bhikshus.

With an Umay cursive Tibetan inscription verso:

This painting of Panjara and retinue is offered by the teacher Kunga Gyatso to the monastic house Ewam Zilnon [with the wish] to completely eliminate the wrong views of those practitioners of the Buddha's teachings and to swiftly pacify all of the outer and inner obstacles.

Panjaranata Mahakala is the protector for the Hevajra cycle of Tantras. His iconography and rituals are found in the 18th chapter of the Vajra Panjara Tantra (canopy, or pavilion), an exclusive 'explanatory tantra' to the Hevajra Tantra itself. Forms of the two armed Mahakala can also be found in the Twenty-five and Fifty Chapter Mahakala Tantras.

Compare with another thangka of Panjaranata with his hair flowing upwards in the Rubin Museum of Art, see Linrothe and Watt, Demonic and Divine, New York, 2004, p. 21, fig. 1.27, and the thangka of Magzor Gyalmo, p. 167, no. 31. Also see Zwalf, Heritage of Tibet, London, 1981, p. 82, no. 41.

Published: HAR #30509 - http://www.himalayanart.org/image.cfm/30509.html

Provenance: Private European Collection

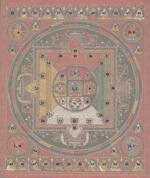

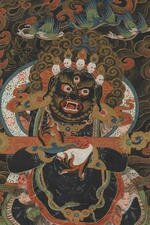

A Chakrasamvara Mandala, Central Tibet, 18th century. Estimate US$ 100,000 - 150,000 (€73,000 - 110,000). Photo: Courtesy of Bonhams.

Distemper on cloth and original silks; multi-armed Chakrasamvara at the centre of a retinue of emanations spreading out in the eight cardinal and sub-cardinal directions, his palace with multi-colored walls and guarded by animal-headed gatekeepers, all within a spherical multi-banded lotus blossom, and pale outer band of the charnel grounds, identified by inscription at the top center is Tsong Khapa (2) flanked by Tilopa (3) and Sachen Kunga Nyingpo (4), at the bottom are the protector deities Charchika (5), Chaturbhuja Mahakala (6), Raven Face Mahakala (7) and an animal faced attendant (8).. Image: 25 1/2 x 16 in. (64.7 x 40.6 cm)

Chakrasamvara is the principal Tantra text of the Anuttarayoga Wisdom (mother) classification of the Vajrayana Buddhist Tradition. Chakrasamvara is also one of the most popular deities in Tantric Buddhism, the Himalayan regions, and Tibet after the 11th century. His purpose and function in the Buddhist Vajrayana system is as a model for meditation practice employed by Tantric practitioners. There is a vast corpus of literature on the subject of Chakrasamvara. The original source material is written in Sanskrit with hundreds of later commentaries, ritual texts, dance performance instructions, and meditation manuals created in the Tibetan.

Compare with three other mandalas in the Palace Museum, Beijing. The treatment of the cloud forms and protector deities in the lower corners are almost identical: Tangka-Buddhist Painting of Tibet: The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, vol. 59, Hong Kong, 2003, nos 216-220.

Also compare with the treatment of the wealth deity Nele Thökar in the Northern wall mural of the Lukhang chapel, Lhasa, see Luczanits, "Locating Great Perfection", inOrientations p. 106, fig. 3. The treatment of the clouds, floral forms and stylized rock elements are almost identical. Also see a forthcoming publication of the entire Lukhang images by Thomas Laird Murals of Tibet, Taschen, due in 2015.

Indian art is also well represented in the sale. Connoisseurs are sure to appreciate a beautifully serene marble Jina from Western India, circa 11th century, from a Private Toronto Collection (est. $60,000-80,000). The sale’s strong Indian painting section will feature an illustration to a ragamala series, Dhanasi Ragini from Bilaspur, 1740 (est. $15,000-20,000). The delicate opaque watercolor and gold illustration was formerly in the collection of George Bickford, a celebrated collector and generous donor to the Cleveland Museum of Arts’ renowned holdings.

A marble figure of a Jina, Gujarat or Rajasthan, circa 11th century. Estimate US$ 60,000 - 80,000 5€44,000 - 58,000). Photo: Courtesy of Bonhams.

Of classic form, with the Jina seated in double lotus on an ornate cushion of foliate motifs in jewel-like cartouches, the hem of his lower garment extending between his ankles, his flexed toes rest above his calves while the line of his tibias course the length of his lower legs, his hands rest in the attitude of meditation below his exquisitely modelled ample stomach, his rib cage rises in iconometrically prescribed diagonals towards his broad chest with the shrivatsa mark between his smooth pectorals, his arms extend from broad shoulders, his neck displays the trivali mark, flanked by the characteristic cubed ends of his pendulous earlobes, his charming face with a pronounced chin and rounded cheeks either side of an abstracted nose rising to high arched eyebrows and elegant almond shaped eyes, his hair in tight curls forming a series of raised nodules enfolding the low ushnisha and a sigmoid hairline. 17 1/4 in. (53.8 cm) high

Few Jain images are as iconic as the white marble meditating Jina. The stone's color connotes the embodied spiritual purity of the Jina, one of twenty-four spiritual exemplars who attained the ultimate goal of liberating their souls from the cycle of death and rebirth. Their image functions to inspire and remind the devotee of the tenets of the faith, as well as its rewards. As Key Chapple notes with reference to a similar, later example in the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, the ornate cushion on which he is seated emphasizes both his status as a revered being as well as his ability to flourish even after surrendering all attachments (Diamond (ed.), Yoga: The Art of Transformation, Washington, DC, 2013, pp. 132-5). He sits in meditation wherein no violence can be envisaged, and meditating on him in turn diverts the spirit away from earthly desire and affliction and towards the transcendent (van Alphen, Steps to Liberation, Antwerp, 2000, p.43).

The sculpture's material originates from the vast marble deposits surrounding the revered Mount Abu, which borders Northern Gujarat and Western Rajasthan. Close interactions between these two regions formed a composite "Maru-Gurjara" style (R Parimoo, Treasures from the Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum, Ahmedabad, 2013, p. 30). Jainism flourished in Western India between the 10th and 12th centuries, with many temples commissioned under the Solanki and Later Pratihara dynasties. The apex of craftsmanship is embodied in the Dilwara temples on Mount Abu itself. Judging from the piece's size and quality, it would likely have served as central devotional image of a smaller temple, or an icon housed in a shrine on the outer perimeter of a larger temple.

Stylistically, this sculpture bears close resemblance in almost all respects to a Jina attributed to the second half of the 12th century found in Gujarat and now held in the British Museum (OA 1915.5-15.1), but the chubbier face and the more naturalistic treatment of the hips and waistline on the present lot suggest a slightly earlier date of production. The archaeological record seems to show a general movement towards greater abstraction in the 12th century. This trend can be observed by contrasting two standing Jinas from Ladol, Gujarat now in the Lalbhai Dalpatbhai Museum, Ahmedabad: one an 11th century figure of Parshvanath (#222), and the other, a figure of Shantinath, dated to 1269 CE (#218, see ibid., pp. 30-1). The former's sigmoid hairline, round face, ushnisha, earlobes, and waist also compare closely with the present sculpture. This development is similarly present when contrasting a Jina attributed to the second half of the 11th century in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1992.131) with the aforementioned example in the Virginia Museum of Arts (2000.98), dated to 1160 CE.

Furthermore, his softly-featured, plump face parallels the attractive modelling on at least two Hindu marble sculptures from 11th century Sirohi: one of Brahmani held in the Albert Hall Museum, Jaipur (CMJ 33/65, see Ahuja, The Body in Indian Art and Thought, Brussels, 2013, no. 149, p. 131) and another, likely of Sarasvati, in the William Price Collection held in the Amarillo Museum of Art (see N. Rao, Boundaries & Transformations, Texas, 1998, fig. 17, p. 22), as well as a Vidyadevi of unknown provenance in the Cleveland Museum of Art (1972.152). Sirohi sculptures are arguably the most attractive type of the style and period. With his sweet expression and uplifting face, the present lot is perhaps the most endearing of its kind.

Provenance: Private Canadian Collection

Acquired from Spink & Son Ltd, London, 1995

An illustration from a ragamala series: dhanasri ragini, Bilaspur, circa 1740. Estimate US$ 15,000 - 20,000 (€11,000 - 15,000).

Opaque watercolor and gold on paper; the maiden with an earnest expression dips her delicate brush into the small ink pot before her, with a near complete portrait of her absent lover tenderly held in the other hand, the attendant behind works a fly-whisk with a rippling tail and another bows in obesiance on a layered carpet, the maiden's forlorn mood is exaggerated by the drooping saplings behind, while an alert spotted cat watches over the covered food and wine bottles. Image: 10 x 6 7/8 in. (25.4 x 17.5 cm)

The presence of the cat in the composition appears to be a popular convention employed by the Bilaspur artists in the early 18th century (see Archer, Indian Paintings in the Punjab Hills, Vol. II, London, 1972, pp. 176- 81, nos. 18i, 24, and 33ii).

Published:: Stansilaw Czuma, Indian Art from the George P. Bickford Collection, The Cleveland Museum of Art, 1975, no. 112

Exhibited: "Indian Art from the George P. Bickford Collection", 16 December 1976 - 13 February 1977, Cleveland Museum of Art; University of Texas, Austin; University of Illinois, Champaign; Fogg Art Museum, Boston; University of Florida, Gainesville; Phoenix Art Museum; University of California, Berkeley; University of Michigan Museum of Art.

Provenance: George Bickford Collection before 1975

Ralph and Catherine Benkaim Collection

E W Art, Pasadena, 2005

Private U.S. Collection

Bonhams Indian, Himalayan & Southeast Asian Art sale will take place on March 17 in New York. The sale will preview March 14-17 at Bonhams New York.

Highlights from the sale will preview February 14-16 at Bonhams Paris office and February 19-21 at Bonhams New Bond Street in London.

Bonhams will host a panel discussion on Nepalese aesthetics at the New York saleroom on March 16. Further information can be obtained by calling (212) 644-9001.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F74%2F94%2F119589%2F128705688_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F56%2F88%2F119589%2F127649882_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F41%2F75%2F119589%2F126978834_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F08%2F51%2F119589%2F126856859_o.jpg)