Sotheby's Paris Impressionist & Modern Art Sale totals outstanding $32.4 million

A fierce battle between six bidders from around the world propelled Amedeo Modigliani’s masterly Portrait of Paul Alexandre to €13,537,500 ($18,401,118) – a new record for the artist in France. Photo: Sotheby's.

PARIS.- The sale total on June the 4th, of €23.8 million ($32,4 million), was Sotheby’s highest-ever for a sale of Impressionist & Modern Art in Paris, with nearly 60% of lots clearing top-estimate – offering clear evidence that the Modern Art market remains dynamic and keen on emblematic market-fresh works.

A fierce battle between six bidders from around the world propelled Amedeo Modigliani’s masterly Portrait of Paul Alexandre to €13,537,500 ($18,401,118) – a new record for the artist in France. This famous painting from 1911/12, which had never previously appeared on the market, portrays Modigliani’s first and most important patron in the years after his arrival in France in 1907. The work’s new owner declared himself delighted to have acquired ‘one of the leading portraits of the 20th century by any artist.’

Aurélie Vandevoorde, Director of Impressionist & Modern Art at Sotheby’s France said, ‘The exceptional price achieved by the Modigliani sets a new benchmark for male portraits by the artist painted before 1914. Its freshness and quality aroused the interest of the world’s foremost collectors.’

Amedeo Modigliani (1884 - 1920, Portrait de Paul Alexandre. Lot sold 13,537,500 EUR. Photo Sotheby's

signed Modigliani (lower right), oil on canvas, 92 by 60 cm ; 36 1/4 by 23 5/8 in.Painted in 1911-12. Estimate 5,000,000 — 8,000,000 EUR.

Provenance: Dr Paul Alexandre, Paris (acquired from the artist)

By descent to the present owner

Exhibited: New York, Museum of Modern Art & Cleveland, Cleveland Museum of Art, Modigliani-Soutine, 1950-51, n.n., titled Dr. Paul Alexandre (Dandy), dated 1911

Martigny, Fondation Pierre Gianadda, Modigliani, 1990, no. 17, titled Paul Alexandre, dated 1911-1912

Düsseldorf, Kunstsammlung Nordhein-Westfalen & Zurich, Kunsthaus, Amedeo Modigliani, Malerei, Skulpturen, Zeichnungen, 1991, no. 11, titled Portrait of Paul Alexandre, dated 1911/12

Literature: Arthur Pfannstiel, Modigliani, 1929, no. VII, p. 5

Jacques Lipchitz, Amedeo Modigliani, 1884-1920, New York, 1954, illustrated pl. 4

Claude Roy, Modigliani, Genève, 1958, p. 33/a

Ambrogio Ceroni, Modigliani, Milan, 1970, no. 23, illustrated p. 44

Joseph Lanthemann, Modigliani Catalogue raisonné, Sa vie, son Œuvre complet, son art, Paris, 1970, p. 109, no. 39, illustrated p. 170

Ambrogio Ceroni & Françoise Cachin, Tout l’œuvre peint de Modigliani, Paris, 1972, no. 15, illustrated p. 89

Claude Roy, Modigliani, Paris, 1985, p. 33

Thérèse Castieu-Barrielle, La vie et l’œuvre de Amedeo Modigliani, Courbevoie, 1987, p. 54

Osvaldo Patani, Amedeo Modigliani, catalogo generale di pinti, Milan, 1991, no. 35, illustrated p. 65

Christian Parisot, Modigliani, Catalogue raisonné, Livourne, 1991, vol. II, p. 270, no. 1/1911, illustrated p. 47

William Rubin et al, Le primitivisme dans l’art du 20e siècle, Les artistes modernes devant l’art tribal, vol. II, Paris, 1991, illustrated p. 356

Noël Alexandre, Modigliani inconnu, Témoignages, documents et dessins inédits de l'ancienne collection de Paul Alexandre, Paris, 1993, no. 331, illustrated p. 69

Anette Kruszynski, Amedeo Modigliani, Portraits and Nudes, Munich-New York, 1996, illustrated p. 11

L’Ange au visage grave (exhibition catalogue), Paris, Musée du Luxembourg, 2002, no. 28, illustrated p. 27, titled Paul Alexandre and dated 1911

Note: Modigliani was ‘noblesse excédée’ to use Baudelaire’s phrase which fits him beautifully. I was instantly struck by his extraordinary talent and I wanted to do something for him. I bought his drawings and canvases, but I was his only buyer and I wasn’t rich. I introduced him to my family. He already had, ingrained in him, the certainty of his own worth. He knew that he was a ground-breaker and not an imitator, but so far he had no commissions. I asked him to paint a portrait of my father, my brother Jean and several of myself” (Noël Alexandre, Modigliani inconnu, Paris, 1993, p. 59).

These lines by Paul Alexandre reveal the decisive role the young doctor played in the ascendance of Amedeo Modigliani’s career and reflect his deep admiration for his artist friend. Paul Alexandre was completing his internship at the hospital Lariboisière in November 1907 when he met Modigliani, the bohemian Italian artist with dandyish style who had arrived in Paris the previous year. Thus began an important friendship that would last until August 1914 when the young doctor was conscripted and left for the front. Alexandre was in effect Modigliani’s first patron and perhaps the most important. It was only after his death in 1968 and especially upon the occasion of the exhibition Modigliani inconnu organised by his youngest son Noël Alexandre at the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen in 1993, that the public were able to discover his incredible collection, comprising no less than twenty-five paintings and a hundred or so drawings (including over a dozen studies depicting himself). The impeccable provenance of these works enabled a new understanding of the early Parisian work of this artist who destroyed so much of his own output. This friendly association that sheltered Modigliani from financial need would prove to be unprecedented in the artist’s career since his subsequent protectors, Paul Guillaume in late 1914, and then Leopold Zborowski from 1916, were dealers first and foremost.

Paul Alexandre, on the other hand, was a true art lover. He and his brother Jean had a group of artist friends from a young age and were instrumental in the creation of a commune known as the Delta that centred around the sculptor Maurice Drouart and the artists Henri Doucet and Albert Gleizes, later joined by the Romanian Constantin Brancusi. At the initiative of Paul Alexandre, in 1907 the circle that had been gathering weekly near the École des Beaux-Arts moved to 7 Rue du Delta in an abandoned municipal building located opposite a spare plot of land. For modest rent, Alexandre transformed the building into a “sort of guardian angel hostel”, a place of reciprocal help and hospitality but above all a site of dialogue for artists, sometimes also the scene of lively festivities and experiments such as the "hashish sessions" organised by the doctor. Alexandre recounted to his son Noël that it was at the Delta that he met Modigliani: “It was Doucet who brought him to the Delta for the first time […] Doucet had met him on Rue Saint-Vincent at Frédéric’s place ‘Au Lapin Agile’, that at the time was only frequented by the poor, by poets and artists … Modigliani told Doucet that he had been evicted from his small studio on Place Jean-Baptiste Clément and didn’t know where to go … Doucet suggested he come to the Delta where he could stay if he wished, and where he could store his belongings. This is how my friendship with Modigliani began. I was 26, he was 23 and my brother Jean was 21.” (Modigliani inconnu, p. 53-54). In his book on Modigliani, Jean-Paul Crespelle relates how the doctor, of limited fortune, deprived himself in order to pay for canvases, and that after opening his clinic at 62 Rue Pigalle, he would have Modigliani drop by on consultation days in order to share the day’s news. He wanted to help his friend but above all desired to own his pictures and admired his immense talent. He preciously conserved most of his collection until his death, almost systematically refusing any exhibition loan requests and even reproduction requests, leading Jeanne Modigliani to comment in her biography of her father: “he was the that increasingly rare breed of collector, a collector who was in love with art in the true sense of the word, to the joy and despair of academics: joy because he pristinely conserved works of indisputable provenance dating from Modigliani’s formative period; despair because he jealously guarded the works and no-one could boast of having seen the entirety of his collection” (Jeanne Modigliani, Modigliani, Une Biographie, Paris, 1990, p. 64).

This portrait of Paul Alexandre from 1911-12 has remained in the family collection for over a century. A rare work, it was only exhibited once during its owner’s lifetime, in 1950-51 in the United States and although the picture is mentioned in this exhibition catalogue, it is not illustrated. It is the fourth portrait of a series of five, completed between 1909 and 1913, and it is by far the most powerful, the one that heralds that inimitable Modigliani style that bestows its models with unparalleled melancholia and sensitivity but that here also reveals an additional modernity that make it a pivotal work. According to Paul Alexandre’s daughter, this portrait was painted just after the death of the sitter’s mother. The burden of his grief infuses this painting with an intimacy and depth that radically set it apart from the other portraits that Modigliani painted of his patron and make it one of his most moving portraits of this period. Paul Alexandre seems to have posed for this portrait, just as he did for the three preceding ones, since we know that only 1913’s Paul Alexandre devant un vitrage (donated by the family to the Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen) was painted from memory – Modigliani gave the painting to his friend as a surprise. The three first depictions, that are more conventional, were painted in 1909 when the doctor introduced Modigliani to his family, and are contemporaneous with the portrait of his father Jean-Baptiste Alexandre au crucifix (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen) and that of his brother Jean (Fondation Gianadda, Martigny). These commissions enabled Modigliani to earn a living and one can imagine that the head of this bourgeois family, who had allowed himself to be persuaded by his son, preferred classical depictions. These portraits of Paul Alexandre are in keeping with the photograph of the young doctor dating from 1909 with this suit, white collar and black tie. The first is a study, while the second, painted against a brown background and the last with a green background present the same scene: the young man turns three-quarters facing the viewer, his right hand in his pocket or on his hip. We sometimes find signs of complicity in the background, such as the painting La Juive from 1907-08 hanging on the wall, one of the very first purchased by Paul Alexandre from Modigliani. Though our portrait, painted a few years later, was probably another commission requested by the patron, its style is strikingly different and more in line with the avant-garde experimentation pursued by his peers Picasso and Matisse and their mentor, Cézanne. The doctor is still recognisable but the composition has been geometrised, as seen by its perfect proportions, characterised by frontality, a vertical axis and economy of colour that clearly show the influence of Cézanne: a detailed, light face contrasting with a dark, dry background at times left unfinished. As Paul Alexandre explained: “He painted by first drawing (often in blue) the outline after contemplating it for a long time. Then he spread his colours diluted in a large quantity of turpentine. He varnished by very carefully spreading a thin layer of polish. Then he rubbed after drying with a chamois or flannel.” (Amedeo Modigliani, Peintures du don Philippe et Blaise Alexandre, Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen, 2002). This portrait, fused with undeniable modernity, is very different from the final version in front of a window painted in 1913 when the artist was beginning to paint again, which elongates the model’s face and evokes the influence of Cubism and Futurism.

Our portrait of Paul Alexandre was in fact painted when Modigliani was turning towards sculpture. From 1910 to 1913, the artist focussed almost exclusively on stone sculpture and created multiple studies for sculpted heads and caryatid motifs – today twenty-five sculptures (all stone except for one in wood and one in marble) have been attributed to him. In April 1909, he left the Delta colony and moved to the Cité Falguière in Montparnasse, around the time that he met Brancusi. After a trip to Livorno and Carrara in summer 1909, the Italian developed his sculpture, considering it to be the pinnacle of art, and wanted to learn the technique of direct carving. Once again Paul Alexandre was the catalyst, for as the doctor explained in his notebooks, as it was he who introduced Modigliani to Brancusi: “Though he was so different from Brancusi, I had an intuition that they would find a mutual understanding through their art. Later it was Brancusi who found him a studio on the Rue Falguière and helped him to prepare his exhibition. They never worked in the same studio, due to their independence and also due to lack of space, but they saw each other frequently and broke bread together […] It would be wrong to believe that either one was the other’s teacher. They were very different but were united in their selfless and perseverant approach to their research” (Modigliani inconnu, p.59). Though few direct accounts exist, the intertwined correspondence between Brancusi, Modigliani and Alexandre reveals that the two artists saw each other very regularly from 1909 onwards, as seen from the Brancusi portrait on the reverse of the painting Le Violoncelliste, 1909. A letter from Brancusi to Alexandre dated 4th March 1911 also indicates that the Romanian helped his friend to set up an exhibition of 25 sculpted heads in the studio of Amadeo de Souza-Cardoso that had been provided for the event. Five archive photographs exist showing the setting up of the exhibition; precious documents since only a few of these stone heads survive today, the others having been either lost or destroyed. The portrait of Paul Alexandre is one of the rare paintings created in this formal context, and if we view the work in juxtaposition with the photographs of these stone heads the visual analogies are striking.

Just like Brancusi, Modigliani refined his technique by simplifying facial features such as the thin nose and almond eyes that characterise his sculpted heads, obtaining an archaic effect that combines diverse influences: Greek and Egyptian sculpture along with the Khmer and Indian art he had discovered at the Musée Guimet with Brancusi and Souza-Cardoso, but also the tribal art of Africa that was very much in vogue in avant-garde circles at the time. Contrary to received opinion, Paul Alexandre recounted that “it was Modigliani who introduced me to African art and not the other way around. He took me to the Musée du Trocadéro where he was passionate about the Angkor exhibition in the west wing” (Modigliani inconnu, p. 67); while one of his mistresses, the Russian poet Anna Akhmotova revealed that in 1911: “Modigliani dreamed of Egypt. He invited me to the Louvre, so that I could visit the Department of Egyptian Antiquities; he said that all the rest wasn’t worthy of our attention” (Christian Parisot, Modigliani, Paris, 2005, p. 173). The influence of primitive art in the widest sense of the term – the art of non-western cultures – was a vehicle for the extreme simplification of volumes in Modigliani’s sculptures that would be translated into expanses of colour in his paintings. In the portrait of Paul Alexandre, Modigliani uses the same radical approach and with very few lines, manages to breathe life into the personality of his model.

If Brancusi played a decisive role in Modigliani’s mastery of direct carving, it is also possible that this emulation was reciprocal. The decorative motif in the background of the present portrait has fascinating similarities with Brancusi’s masterpiece, La Colonne sans fin. The precise date of this wooden tower’s conception has never been determined by historians; however it appears to be between 1916 and 1918, thus several years after this picture was painted. The work of Sidney Geist, a Brancusi specialist, points to a common source for this vertical band constructed from lozenge shapes. When in 1968 Geist questioned Madame Brefort, Paul Alexandre’s daughter, regarding the iconography of her father’s portrait, she replied that it was highly likely that Modigliani had taken inspiration from a Moroccan or African wall-hanging that was in Paul Alexandre’s home at the time. Even though this wall-hanging has not been found, the doctor’s daughter remained convinced that it was not invented by the artist. (Sidney Geist, "Le devenir de la colonne sans fin" in Les carnets de l’Atelier Brancusi, Paris, 1998, p. 16). Given the bond between Paul Alexandre, Modigliani and Brancusi, the Romanian sculptor must have also known of this wall-hanging either through his fellow artist or by his own visits to the doctor’s home. This type of textile, generally originating from central Africa, for instance the Kuba textiles of the Democratic Republic of Congo, was in fashion at the time among avant-garde artists and African art connoisseurs; Matisse was a passionate collector of fabrics and owned a large panel by the 1920s, if not before.

When Modigliani arrived in Paris, the art of Sub-Saharan Africa was just being discovered by the artists he met such as Picasso, Matisse, Derain and Vlaminck, who all collected tribal art. Matisse recounted that he had purchased his first wooden statue of African origin in an exotic curiosity shop as early as 1906 while the Hungarian antique dealer Joseph Brummer expanded his business into Pre-Columbian and African art from 1908. Modigliani spent time in this milieu and saw these African statues, notably at the homes of his friends the sculptors Jacques Lipchitz and Jacob Epstein and in the studio of the painter Frank Burty Haviland. However as Alan G. Wilkinson explains in the catalogue for the exhibition Le Primitivisme dans l’art du 20e siècle (1987), Modigliani took a different approach from his peers who mixed difference tribal influences. For the creation of his sculpted heads and later his portraits he essentially took inspiration from the masks of Ivory Coast baoulé dancers and ceremonial Fang and Punu masks from central Africa – such as the one visible on the wall of Picasso’s studio behind Frank Haviland in 1910.

The 1911-12 portrait of Paul Alexandre is in keeping with this primitive style that was a total break from conventional art, reflected in in the fine features of the face with the contours of the eyes outlined by the eyebrows, as the sitter himself recalled: “In his drawings there is an invention, a simplification and a purification of form. This is why he was so seduced by African art. Modigliani reconstructed the lines of the human face in his own fashion by positioning them within the context of African art. He took pleasure in attempting to simplify lines and applying this to his personal research.” (Amedeo Modigliani, Peintures du don Philippe et Blaise Alexandre).

Whether in his incredible stone sculptures or in his paintings, Modigliani was above all a great portraitist who, following in the footsteps of his peers Matisse and Picasso, was able to free himself entirely of the classical portraiture genre in order to express a new sensitivity. Taking inspiration from diverse primitive sources, he dispenses with all that is superfluous, transcending the model in order better to represent him. The finest tribute would come from his first admirer, Paul Alexandre himself: “Whosoever looks at his portraits of women, youths, friends and others, will find a man a man of exquisite sensitivity, tenderness, pride, passion for the truth and purity” (Modigliani inconnu, p. 67). The 1911-12 portrait of the man who was like a brother to the artist until the outbreak of war in 1914 (the two men would never see each other again after Alexandre returned from the front, as the Italian was by then associated with the young dealer Paul Guillaume whom the doctor disliked) is the most powerful from a stylistic point of view, and the most radical of the series. It foreshadows the portrait of the collector Roger Dutilleul, painted in 1919, but above all takes its place in the canon of portraits of artists’ protectors that have become icons of modern art, such as the portraits of Ambroise Vollard painted by Cézanne in 1899, of Gertrude Stein by Picasso in 1906, or later Auguste Pellerin by Matisse in 1916.

Vérane Tasseau

A number of other high prices were obtained during the sale for iconic works of modern art seldom seen at auction.

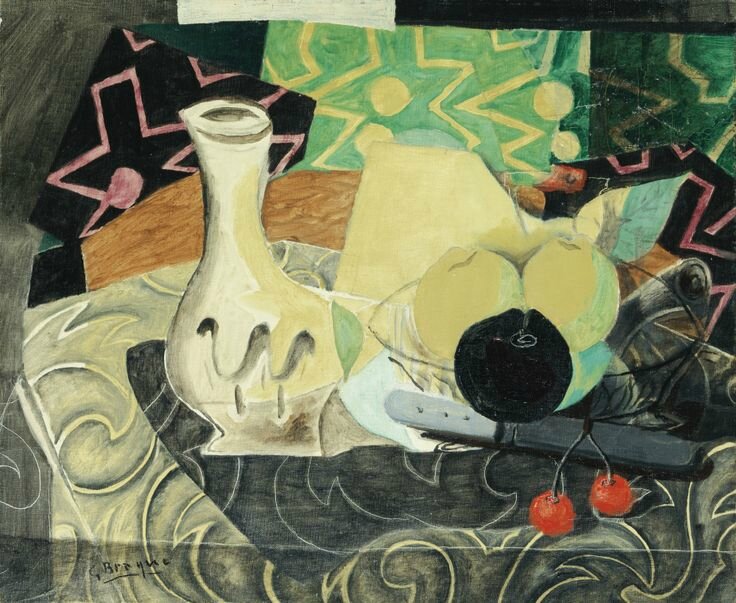

Georges Braque’s exquisite Still Life with Cherries from 1936, a period from his oeuvre seldom seen on the market, obtained €1,261,500 ($1,714;,719) – a price in keeping with its rarity and quality (lot 19, est. €600,000-800,000).

Georges Braque (1882 - 1963), Nature morte aux cerises. Lot Sold. 1,261,500 EUR. Photo Sotheby's

signed G Braque (lower left), oil on canvas, 38.7 by 46.4 cm ; 15 1/4 by 18 1/4 in. Painted in 1936. Estimate 600,000 — 800,000 EUR.

Provenance: Paul Rosenberg & Co., New York

William March, New York

Perls Galleries, New York

Galerie Katia Granoff, Paris

Sale : Champin, Lombrail & Gautier, Enghien, 21 November 1991, lot 11

Private Collection, Switzerland

Galerie Cazeau-Béraudière, Paris

Private Collection (acquired from the above on 3 March 2004)

Acquired from the above by the present owner in July 2009

Exhibited: New York, Perls Galleries, The William March Collection of Modern French Masterpieces, 1954, no. 5

Literature: Nicole Worms de Romilly, Catalogue de l'œuvre de Georges Braque, Paris, 1973, vol. 4 : peintures 1936-1941, illustrated p. 9

Note: Painted in 1936, Nature morte aux cerises shows Georges Braque’s constant fascination for still-lifes, dating from his Cubist period. In the 1930s, Braque produced a succession of extremely decorative still-lifes through which he continued his formal and pictorial exploration. The same objects often reappear, pedestal tables, tablecloths, fruit bowls, jugs, as we can see from another composition painted the same year, today housed in the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In these compositions, the decorative imagination of Braque achieves its zenith. Borrowing compositional methods from Cubism which he developed with Picasso, he adds another dimension by choosing shimmering and refined colours.

The selection and processing of objects is far from arbitrary and is the result of aesthetic research into the balance between space and objects that make up the still life. Braque explained this process in an interview with Georges Charbonnier on France-Culture: "(people) seem to totally ignore that what is between the apple and plate is painted too (...). This in-between seems to me just as important as the object itself. It is precisely the relation of these objects between themselves and between the object and this in-between which constitutes the subject" (quoted in Fondation Maeght, Georges Braque, 1994 , p.174 ). In Nature morte aux cerises Braque juxtaposes light and dark tones to distinguish the objects of the still-life from the tablecloth, wallpaper and curtains. The wood effect used for the table recalls thepapier collé technique developed by Braque and Picasso during their famous collaboration.

The still-lifes of the thirties are an essential milestone in Braque’s work. Still loyal to the Cubist aesthetic, they nevertheless introduce new dimensions of volume, ornamental treatment, dynamic black and white elements and especially colour, but without weakening the cohesion of the image. Midway between Cubism and the temptation of metamorphosis, using breakaway forms and free arabesque motifs,Nature morte aux cerises showcases this fascination for interior objects, a continued aesthetic research that would lead to the famous Ateliers series that Braque developed a few years later.

Pablo Picasso’s The Artist and his Model (1964), a work of stupefying energy laced with eroticism, fetched the sale’s second-highest price of €3,009,500 ($4,090,723) (lot 23, est. €2.2-2.8m).

Pablo Picasso (1881 - 1973), Le peintre et son modèle. Lot sold. 3,009,500 EUR. Photo Sotheby's

signed Picasso (upper right) ; dated 13/14.11.64 (on the reverse), oil on canvas, 97.9 by 130.5 cm ; 38 1/2 by 51 3/8 in. Painted on 13th and 14th November 1964.Estimate 2,200,000 — 2,800,000 EUR

Provenance: Galerie Louise Leiris, Paris

Galerie Karsten Greve, Cologne

Private Collection, Europe

Private Collection, Suisse

Acquired from the above by the present owner

Exhibited: Cologne, Galerie Karsten Greve, Pablo Picasso, 1988, no. 62

Literature: Christian Zervos, Pablo Picasso, vol. XXIV : œuvres de 1964, Paris, 1971, no. 267, illustrated p. 101

Note: “That the artist at work – almost always “the painter and his model” who appears as a major theme in Picasso’s oeuvre – became, not a unique theme, but at least the most frequently revisited one, shows us the importance the act of painting had in Picasso’s eyes.”

Michel Leiris, 1963 (in Jean Leymarie, Picasso. Métamorphoses et unité, Genève, 1971, p. 191)

“Picasso painted, drew and engraved this subject so many times in the course of his life, from every possible angle, that it almost became a “genre” in itself, like the landscape or the still-life. In 1963 and 1964, he barely painted anything else.” This comment from Marie-Laure Bernadac (in Picasso. La Monographie 1881-1973, Barcelone, 2000, p. 439) reveals the importance of the iconic theme of the Painter and his Model in Picasso’s art. Though the subject appears early in the painter’s oeuvre, notably in a 1926 picture painted at the request of Ambroise Vollard (Le Peintre et son modèle, 1926, Musée Picasso, Paris) and two years later in a sumptuous 1928 composition today conserved at the Museum of Modern Art inNew York, it was above all at the end of this life, in the 1960s, that it became a central theme.

From 1963 onwards Picasso approached the theme of the Painter and his Model with something approaching frenzy. He had just moved to Notre-Dame-de-Vie in Mougins and the series of works he devoted to this theme correspond to his appropriation of his new studio. For several months (from February to May 1963 and then October to December 1964, when the present canvas was painted), he devoted himself almost exclusively to this subject, translating his creative passion directly onto the canvas, without any preparatory sketches. During this period of intense creativity, he painted almost 150 canvases depicting the painter and his model. More often than not, as is the case with the present work, the painted appears with his traditional attributes (paintbrush and palette) face to face with nude model, who is sitting or lying. The easel with its canvas serves to separate the picture into two parts, corresponding to two distinct worlds: that of the artist and that of the model.

More than an evocation of his own work, in these iconic paintings Picasso strives to create an homage to the very profession of being an artist. Nearing the end of his life, after close to a decade spent reinterpreting the great masters of the past (notably his works dedicated to Velasquez’s Meninas, Delacroix’s Femmes d’Alger, Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe de Manet and Poussin’s L’Enlèvement des Sabines), in this series the aging artist returns to the essence of his vocation: painting from a life model. A shining manifesto illustrating his conception of the painter’s profession. in opposition to the trends in contemporary art at the time, in the present work, by depicting the very act of painting, Picasso strives to reveal to the spectator the complex relationship between the painter and his model. Though the model, with her raw sexuality, incarnates the real world, she only exists in terms of the artist’s gaze, the starting point for all creativity. Painted in pastel tones that contrast with the eroticism of the composition, this picture highlights the intertwined and magical relationship between the two protagonists, the spectator appears here in the role of voyeur encroaching into the intimate world of the artist’s studio. As Jean Leymarie expresses, “The Painter and his Model is the dialogue between art and nature, between painting and the real” (in Jean Leymarie, Picasso. Métamorphoses et unité, Geneva, 1971, p. 279), a final testament from Picasso at the zenith of his art.

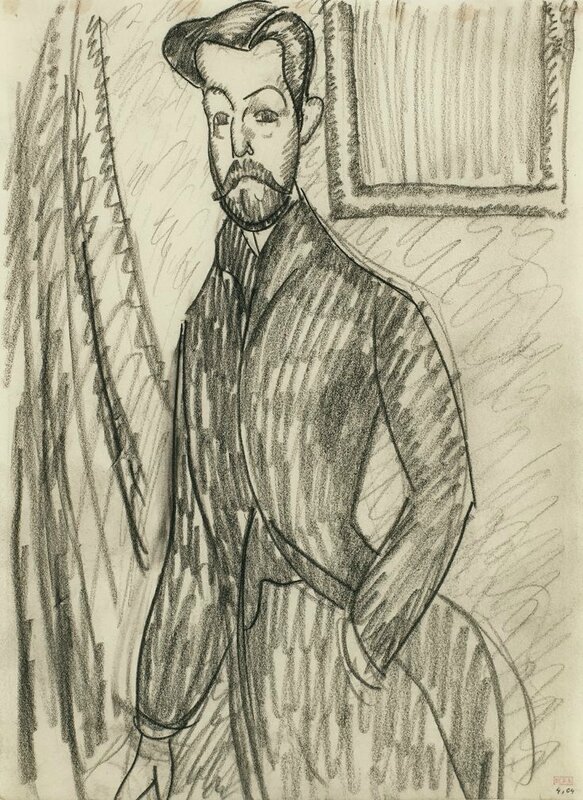

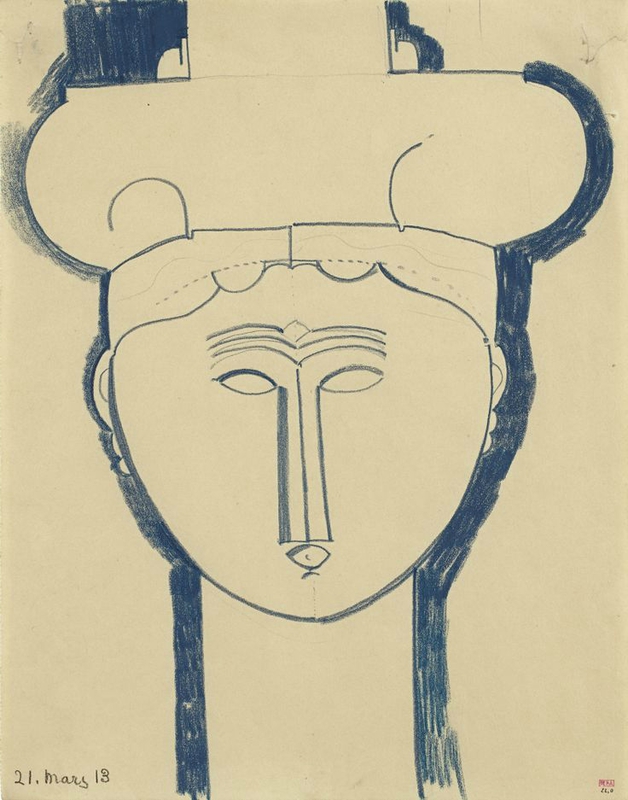

The sale also featured a superb ensemble of drawings by Amedeo Modigliani, including a Portrait of Paul Alexandre in three-quarter profile with his left hand in his pocket (1909) showcasing the artist’s incomparable virtuoso technique, that sped by past top-estimate to €505,500 ($687,111) (lot 10, est. €200,000-300,000); and a 1913 blue crayon Tête de Cariatide that climbed to €313,500 ($377,197) (lot 13, est. €120,000-180,000).

Amedeo Modigliani (1884 – 1920), Paul Alexandre vu de trois quarts, la main gauche dans la poche. Lot sold. 505,500 EUR. Photo Sotheby's

stamped DE P.A. and numbered 4.04 (lower right), crayon on paper,27 by 19.7 cm ; 10 5/8 by 7 3/4 in. Executed in 1909. Estimate 200,000 — 300,000 EUR

Provenance: Dr Paul Alexandre, Paris (acquired from the artist)

By descent to the present owner

Exhibited: Venice, Palazzo Grassi ; London, The Royal Academy of Arts (travelling exhibition also passing through Cologne, Madrid, Bruges, Tokyo, Luxembourg, New York, Montreal & Rouen), Modigliani inconnu : Dessins de la Collection Paul Alexandre, 1993-96, no. 331

Literature: Noël Alexandre, Modigliani inconnu, Témoignages, documents et dessins inédits de l'ancienne collection de Paul Alexandre, Paris, 1993, no. 331, illustrated pl. 412, p. 420

Osvaldo Patani, Amedeo Modigliani, Catalogue Generale, Disegni 1906-1920 con i disegni provenienti dalla collezione Paul Alexandre (1906-1914), Milan, 1994, no. 777, illustrated p. 350

Note: The present work is one of series of portraits Modigliani made of his patron Paul Alexandre in the year 1909. The two men had known each other for two years and had become close friends. After persuading his father, Jean-Baptiste Alexandre, to sit for the young painter in 1908, in 1909 Paul Alexandre himself agreed to pose. The result was three paintings, all painted the same year, as well as a beautiful group of drawings (numbered 408 to 414 in the catalogue by Noël Alexandre, Modigliani Inconnu, Dessins de la Collection Paul Alexandre, Paris, 1996). These drawings, in which Paul Alexandre adopts more or less the same pose, all appear to be studies for the two majestic portraits Paul Alexandre sur fond brun (Tokyo Fuji Art Museum, Tokyo) and Paul Alexandre sur fond vert. The present drawing is undeniably the most accomplished of the series: though the face bears the most similarity with the painting Paul Alexandre sur fond vert, the pose of the model with his hand in his pocket, is that adopted by Modigliani in the painting Paul Alexandre sur fond brun.

This portrait differs from Modigliani’s later portraits of his patron (between 1911 and 1914). Whereas the 1909 portraits are urbane, depicting Paul Alexandre in an aristocratic pose against opulent decor, the later portraits are more introspective. The present drawing demonstrates the artist’s masterful technique. The pencil strokes are extremely confident, with no hesitation, while the composition creates an impression of balance and dynamism: the folds of the curtain echo the curves of the suit, creating an ascending movement, and the visible frame in the foreground introduces vertical and horizontal lines that structure the ensemble. We see the remarkable technique so praised by Alexandre himself in these terms: “His great post-war creations were long thought-out and developed. He would then produce a masterpiece. [...] When he had a figure in mind, he drew feverishly, at amazing speed, never correcting himself, restarting the same drawing ten times in the same evening by candlelight, in order to obtain the desired contour in a satisfying way. Therein lies the purety and incomparable freshness of his finest drawings” (in Noël Alexandre, Modigliani Inconnu, Dessins de la Collection Paul Alexandre, Paris, 1996, p. 65).

Amedeo Modigliani (1884 – 1920), Tête de cariatide surmontée d'architecture. Lot sold. 313,500 EUR. Photo Sotheby's

dated 21. Mars 13 (lower left) ; stamped DE P.A. and numbered 22.0 (lower right), blue pencil on paper, 33.6 by 26.4 cm ; 13 1/4 by 10 3/8 in. Executed on 21 March 1913. Estimate 120,000 — 180,000 EUR

Provenance: Dr Paul Alexandre, Paris (acquired from the artist)

By descent to the present owner

Exhibited: Venice, Palazzo Grassi ; London, The Royal Academy of Arts (travelling exhibition also passing through Cologne, Madrid, Bruges, Tokyo, Luxembourg, New York, Montreal & Rouen), Modigliani inconnu : Dessins de la Collection Paul Alexandre, 1993-96, no. 168

Literature: Noël Alexandre, Modigliani inconnu, Témoignages, documents et dessins inédits de l'ancienne collection de Paul Alexandre, Paris, 1993, no. 168, illustrated pl. 258, p. 297

Osvaldo Patani, Amedeo Modigliani, Catalogue Generale, Disegni 1906-1920 con i disegni provenienti dalla collezione Paul Alexandre (1906-1914), Milan, 1994, no. 957, illustrated p. 397

Note: "Undoubtedly, Modigliani's most powerful drawings are the drawings of a sculptor" (François Bergot, 'L'Ange au visage grave', in Noël Alexandre, Modigliani inconnu, Paris, 1993, p. 8).

It is unquestionably in his drawings of caryatids that Modigliani's predilection for sculpture is most powerfully expressed. This ancient theme of idealised female figures, conceived as architectural columns, became an obsession for the artist during his early years in Paris. His ambition was to create a monumental series of stone caryatids but his deteriorating health limited the scope of his production in this medium, and he instead devoted himself to a two-dimensional exploration of the theme, executing over 60 drawings and studies. Modigliani's caryatids, with their highly stylised, geometric forms, take inspiration from the tribal artefacts he had discovered in the company of his patron and friend Paul Alexandre at the Musée du Trocadero in 1910, and also recall the sculptures of Constantin Brancusi, who similarly sought to reduce the human form to minimal sculptural elements.

This frontal female portrait is one of the final sketches in this series, completed before the artist's departure for Livorno in April 1913, and shows the concluding stage of his process of conceptualising the metamorphosis from head to capital. Modigliani was awestruck by his encounter with Khmer limestone archaeological heads and strove to mimic their simplicity in his sketches, evoking their grandeur and permanence as well as their austerity. His deliberate mirroring of drawn elements demonstrates a captivation with geometric order and symmetry yet, in the stray marks in the background, he also reveals the inherently “imperfect” process of free artistic experimentation at play. This duality between the perfect ideal of symmetry and his freedom of expression as a draughtsman is noted by Noël Alexandre: "Modigliani pursued his search for ideal beauty in the simplest of forms with tenacity and intelligence... The more rigorous the symmetry, the greater his freedom in expressing the essential truth. Clearly this lies behind the vertical formats and the stress on frontality that are found in the drawings." (quoted in: The Unknown Modigliani, 1993, p. 241)

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F25%2F77%2F119589%2F129711337_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F60%2F34%2F119589%2F128961949_o.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F84%2F21%2F119589%2F128701730_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F96%2F14%2F119589%2F128351398_o.jpg)