Bonhams announces a strong lineup for the upcoming Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Art Sale

Gilt copper figure of Chakrasmvara, estimated at $400,000-600,000. Photo: Bonhams.

NEW YORK, NY.- Following the resounding success of the Himalayan sale in March, Bonhams announces their upcoming Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Art Sale to be held in New York on 14th September, 2015. With over 123 lots and total estimates of US$2 3 million, the sale provides a selective offering of fine Himalayan bronzes and thangkas, Indian stone and Indian miniatures.

Highlights include, a magnificent gilt copper alloy figure of Chakrasamvara, Tibet, 15th century estimated between $400,000-$600,000. The piece expresses one of the most important transcendental ideals in Buddhist art – the supreme bliss of enlightenment attained through the perfect union of wisdom and compassion. It is a masterpiece of Tibetan sculpture.

A gilt copper alloy figure of Chakrasamvara, Tibet, 15th century. Estimate US$ 400,000 - 600,000 (€360,000 - 530,000). Photo: Bonhams.

Provenance: Christie's, London, 6 May 1975, lot 50

Phillip Goldman Collection, 1975-2002

Sotheby's, New York, 21 March 2002, lot 161

Private Wisconsin Collection

Notes: Through its beauty, complexity, and vigor, this masterpiece of Tibetan sculpture expresses one of the most important transcendental ideals in Buddhist art the supreme bliss of enlightenment attained through the perfect union of wisdom and compassion (skillful means).

The male deity, Chakrasamvara, represents Buddha-like compassion. The female deity, Vajravarahi, embodies Buddha-like wisdom. They are depicted here in ecstatic embrace. He cradles her in his primary arms, producingvajrahumkara mudra by crossing the vajra and ghanta in his hands, symbolizing that wisdom and compassion have dissolved into one perfect interpenetrative union.

The sculpture wondrously unifies such dualities. Predominant diagonal registers extend from the outstretched elephant skin behind his shoulders to his feet, crossing the primary hands and further emphasizing the vajrahumkaraimagery. The symmetry of his arms contrasts the sway of his bent knees and sweeping festoons. He is at once solid yet fluid, powerful yet graceful. With his arresting eyes piercing forward from the furrowed brow, the sculpture's overall effect is somehow hieratic yet enigmatic.

Its finer details are meticulously executed. Almost tucked out of view, his upper thighs are clad in intricate textiles. His attributes are inventive, such as the curved shaft of his axe, the twisted locks of Brahma's head, and the chased rim of his curved knife. The rich gilding is punctuated with inset turquoise each jewelry element confidently chased. Vajravarahi wears the panchamudra, or 'five ornaments', worn by females of the highest yoga tantra. Her apron, in particular, mesmerizes with its complex interlaced floral medallions and ghanta pendants.

Compare the apron, long beaded festoons with circular pendants, crown types, broad faces, and knitted brows with two 15th-century Chinese silk images of the deity in private collections: www.himalayanart.org/items/101608 & www.himalayanart.org/items/90916. Also compare a 15th-century Nepalese paubha published in Huntington, Leaves from the Bodhi Tree, Dayton, 1990, no. 117. Lastly, compare related sculptural examples published in von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, Hong Kong, 2001, nos. 264C & 270D, and a bronze of Hevajra from a Shakya monastery: www.himalayanart.org/items/31935.

Featuring prominently across all Tibetan Buddhist schools, gilt bronze figures of Chakrasamvara with Vajravarahi demanded the best craftsmen in order to produce complex meditational images that could both express and inspire the most exquisite state of mind.

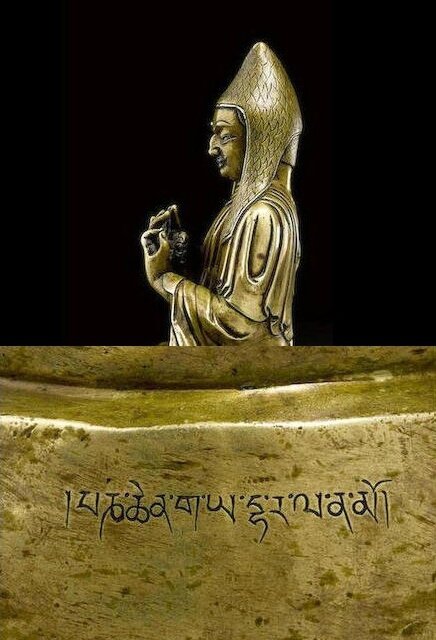

A remarkably rare piece in the sale is a silver and copper inlaid copper alloy figure of Gayadhara, Tibet, circa 15th century estimated at $100,000-$150,000. Another highlight, it represents the Indian pandita, Gayadhara, an important Indian guru crucial to one of the most significant esoteric Tibetan Buddhist Practices. Interestingly, it is one of the few known identified portraits of Gayadhara.

Seated in dhyanasana on a distinctive copper-inlaid lotus base with a thick beaded lower rim, his hands indharmachakrapavartina mudra, his authoritative portrait inlaid with silver; inscribed on the reverse: pan chen ga ya dha ra la na mo; "homage to great Panditya Gayadhara."; 8 3/8 in. (21.3 cm) high

Provenance: William O. Thweatt, Nashville, acquired in Kathmandu between 1958-1962, during his time with the Ford Foundation and Aid Agency International, and while serving as an economic advisor to the King of Nepal

E W Art, Pasadena, 2004

Kapoor Galleries, New York, 2008

Collection FKH, USA

Referenced: HAR - himalayanart.org/items/33036

Notes: Identified here by the beautifully incised Tibetan inscription, this is a rare and commanding portrait of the Indian master who brought the Lamdre teachings to Tibet.

The sculptor has given the portrait a powerful presence. Silver-inlaid eyes and facial hair, and a distinctive hooked nose evident in profile, enliven his visage. His pandita hat bears incised tuft-like markings evoking the textured red material used for monastic caps of the Shakya order. Gayadhara's robe is drawn tight around his powerful frame and falls in delicate folds at the back.

At the heart of the Shakya order is the Lamdre transmission lineage. First enunciated by Mahasiddah Virupa, Gayadhara (d. circa 1103) brought the teaching from India to Tibet - and transmitted the lineage to the industrious Tibetan translator Drogmi Shakya Yeshe (990-1074).

Also known as "The Path with the Result", the Lamdre teaching, "is a vast and complex system of theory and practice, said to contain everything necessary for the attainment of complete enlightenment in one lifetime...The tantric practices should only be attempted under the guidance of a qualified master of this system." (Stearn, Taking the Result as the Path, Somerville, 2006, p. 7.)

So prized are these teachings that at least two emperors of China were initiated into the practice, richly compensating their masters. The Northern Song Emperor Renzong was initiated in 1055. The Yuan Emperor Kublai Khan (r. 1260-94) was initiated by his imperial tutor Chogyel Pagpa, who was then rewarded with the thirteen districts of Tibet.

Bolstered by Yuan imperial sanction, the Shakya order rose to great prominence in subsequent centuries, developing grand complexes such as Ngor monastery and Pelchor Chode in Gyantse. The latter likely served as the place of production for the present lot.

Complemented by similar inscriptions and distinctive alternating copper inlaid lotus petals, there are two other sculptures from the same atelier: one of Shalupa Sangye Pelzang in the Oliver Hoare Collection (see Portraits of the Masters, London, 2003, p.266, no.74); the other of Lama Dampa Sonam Gyaltsen in the Rubin Museum of Art (HAR#203; Weldon & Casey, Faces of Tibet, Carlton Rochell, 2003, p. 70, no. 34). Discussing the latter, Rhie suggests it was made at Pelchor Chode because it bears so close a likeness to Shakya lama sculptures held there (Rhie & Thurman, A Shrine for Tibet, New York, 2009, p. 20, fig. 5).

With only a handful known, sculptures of Gayadhara are extremely rare. One is preserved in Mindroling monastery (see von Schroeder, Buddhist Sculptures in Tibet, 2001, p. 979, no. 238C) and another is published in Chenbaizhong, Sattva & Rajas: The Culture and Art of Tibetan Buddhism, 2004 (HAR#32257). A contemporaneous portrait thangka sharing similar facial features is published in Rhie & Thurman, Wisdom and Compassion, New York, 1996, pp. 206 and 207, no. 64.

Another standout lot is a copper alloy figure of Tara, Tibet, Pala style, circa 12th century, estimated at $150,000-$250,000. This gemlike bronze was created during a time of prolific cultural exchange between the Pala monastic universities of Bengal & Bihar and Central Tibet, known as the Chidar, or ‘Later Diffusion of the Faith’. This provides a superior example of early Tibetan sculpture drawing inspiration from Eastern Indian Pala bronzes.

A copper alloy figure of Tara, Tibet, Pala style, circa 12th century. Estimate US$ 150,000 - 250,000 (€130,000 - 220,000). Photo: Bonhams.

Standing elegantly between sinuous lotus stems in bloom by her shoulders, she gestures teaching and wish-granting, her diaphanous dhoti and uttariya clinging to her supple hips and breasts, and her face and hair with remains of cold gold and blue pigment. 8 1/8 in. (20.5 cm) high

Exhibited: Harvard University Art Museum, Cambridge, MA, 2002-2008

Fitchburg Art Museum, Fitchburg, MA, 2010-2015

Provenance: Collection FKH, USA

Referenced: HAR - himalayanart.org/items/33013

Notes: These standing and seated Taras (lots 16 and 17) are superior examples of early Tibetan sculpture drawing inspiration from Northeastern Indian Pala bronzes. They were created during a time of prolific cultural exchange between the monastic universities of Northeastern India and Central Tibet. Between the 10th-12th centuries, Tibetan pilgrims in search of the "pure" form of Buddhism in the land of Buddha's enlightenment were so moved by the philosophical teachings and material culture at monasteries like Nalanda and Vikramshila in Bihar that they sought to replicate it in their own culture. This transmission is known as the Chidar.

In this period, new monastic orders were created around the teachings of the Tibetan translator Marpa (1012-1096) and Indian masters, such as Atisha (982-1054), Padmasambhava (8th century), and Virupa (9th century) namely the Kagyupa, Kadampa, Nyingmapa, and Sakya orders, respectively.1 And just as Indian monastic structures and teachings composed much of the foundation of Tibetan Buddhism, so too Pala sculpture formed the crucible from which much of Tibetan art developed.

The Pala style, particularly of the latter 11th-12th centuries, is typified by an overall high technical execution broaching the precision of jewelry making. Seen for example in a fine Pala Manjushri sold at Sotheby's, New York, 24 March 2011, lot 26, slender yet shapely waists, sinuous lotus stems, beaded anklets, tall headdresses, and armlets, necklaces, and crowns inspired by foliate imagery characterize the style, exemplified in our two Taras as well.

The present bronzes echo the high aesthetic accomplishments of the late Pala style. The lotus pedestals are attempted in the round. The hands are carefully contoured and the fingers elegant. The dhotis are sumptuous and the lotus stems spirited. The bronzes communicate the grace, serenity, and reassurance of the deity.

While it is generally assumed that Tibetan renditions fail to exhibit the same quality in metal casting as Northeastern Indian prototypes, even a cursory glance through the corpus of Pala bronzes actually reveals that our two Tibetan Taras exceed the craftsmanship of many Pala originals. Compare the level of detail, for instance, on a Pala standing Manjushri and a seated Tara held in the Los Angeles County Museum.2

In fact, these two Tibetan Taras not only surpass many Northeastern Indian bronzes, but their faces and physiognomy - with their sumptuous waists and pert breasts - so closely adhere to the Pala emphasis on grace and femininity that at least one of the following extrapolations can be made. These figures were produced while the Pala monasteries were still active, thus preceding other copies that stray further from Pala idioms.3 These figures were produced under or after the close instruction of Northeastern Indian masters. These figures were produced by Northeastern Indian craftsmen working in Tibet their divergence from Pala prototypes resulting from changes in patronage, material, and/or casting conditions. As such, these two sculptures are fine examples attesting to the transmission and survival of Buddhist sculptural traditions from India to Tibet.

Out of this phase of 'apprenticeship' of Northeastern India, Tibetan sculpture matured to develop its own distinct styles. Yet the Pala legacy lingered and reverberated throughout Tibetan history, the Indian arhats and mahasiddas remaining key figures in all lineages. In the 18th century, the Pala style was introduced and revitalized at the Chinese court. A devout Gelugpa Buddhist, the Qianlong emperor collected and reproduced Pala and Tibetan Pala-style bronzes. The Qing Palace Collection contains at least sixteen Pala 10th-12th century examples and sixteen Tibetan Pala-style 12th-13th century bronzes.4 From these prototypes, the emperor commissioned numerous copies, ushering in a sub-school of Qing Buddhist bronzes known as Pala Revival.5

1. See Heller, Tibetan Art, Milan, 1999, pp. 124-6.

2. Pal, Indian Sculpture, Los Angeles, 1988, pp. 206 & 208-9, nos 102 & 104.

3. Contrast against the following 13th-century examples published in: Uhlig, On the Path to Enlightenment, Zurich, 1995, p. 142, no. 89; Weldon, The Sculptural Heritage of Tibet, London, 1999, p. 56, fig. 19; Zangchuan fojiao zaoxiang-Gugong bowuyuan cang wenwu zhenpin quanji, Hong Kong, 2008, p. 129, no. 123.

4. For Pala examples, see Zangchuan fojiao zaoxiang-Gugong bowuyuan cang wenwu zhenpin quanji , Hong Kong, 2008, pp. 43-59, nos 42-57; for Tibet Pala-style examples, see ibid., pp. 110-3, 115-23, 128-9, & 131-2, nos 105-8, 105-17, 122-3, & 125-6.

5. See examples, ibid., pp. 242, 245 & 253-7, nos 231, 234, & 242-6.

In a sale that features works of excellent provenance there is also a group of Tibetan thangkas from the collection of the late Tibetan scholar Lobsang P. Lhalungpa. Among his collection is an exquisite thangka depicting Arhat Pindola Bhadravajra, one of Buddha’s four original disciples. A thangka from an Arhat series: Pindola bharadvaja, Eastern Tibet, Palpung style, 18th century is estimated $20,000-$30,000.

A thangka from an arhat set: Pindola Bharadvaja, Eastern Tibet, Palpung style, 18th century. Estimate US$ 150,000 - 250,000 (€130,000 - 220,000). Photo: Bonhams.

Distemper on cloth; with Tibetan inscriptions identifying the subject in gold recto, in ink verso. Image: 33 1/4 x 24 5/8 in. (84.5 x 62.6 cm); With silks: 60 x 31 1/2 in. (152.4 x 80 cm)

Referenced: HAR - himalayanart.org/items/31511

Provenance: Collection of Lobsang P. Lhalungpa (1926-2008)

Acquired either in Tibet before 1947 or India before 1971

Notes: This exquisite thangka is the twelfth of a known Sixteen-Arhat set. Twelve are published on Himalayan Art Resources: www.himalayanart.org/search/set.cfm?setID=3005. Each is photographed with its silk mounting, confirming the present lot survives with its original orange and silver brocade.

The painting's style and composition are derived from the refined 'Encampment style' developed by Situ Panchen at Palpung monastery. The composition, with its controlled brushstrokes, grassy knolls, gold-outlined blue and green rock formations, and light tonal gradients, is similar to an Avadanakalpalata set held at Palpung monastery, commissioned by Situ Panchen in 1737 (see Jackson, Patron and Painter, New York, 2009, pp. 12 & 124, fig 6.11).

Identified by the alms bowl and book in his hands, Arhat Pindola Bharadvaja sits on a Chinese-style throne near the center of the painting. The surrounding landscape illustrates important moments in his life. Starting from the bottom right corner and moving clockwise: Pindola Bharadvaja, in his mother's arms, grew up in palatial settings. The son of a regent of Rajagriha, he had a privileged birth, but grew dissatisfied with his lot after being exposed to Shakyamuni's teachings. Seen leaving the palace, he renounced his noble life and became an initiate of Shakyamuni.

Holding an alms bowl and staff near a village in the bottom left corner, Bharadvaja achieved arhat consciousness through perfecting the twelve forms of asceticism particularly that overcoming gluttony and living solely off of one's daily alms round. The name 'Pindola', in fact, translates into Tibetan as 'seeker of alms'.

Shakyamuni gave Pindola Bharadvaja the epithet, 'greatest of the lion roarers' because he excelled at discourse, championing Shakyamuni's teachings to disciples and laity. Above the bottom left corner, we see the arhat teaching to the population of Kaushambi. From the right comes King Charka of Badsa with an entourage of three attendants and the elephant of ignorance in their wake. The king had heard of the sage and wanted to pay him a visit on his way to a hunt. When Pindola Bharadvaja neglected to rise from his seat to greet the king, the king left feeling insulted. He plotted to return later that day and, if he were not afforded due courtesies, planned to chop off Bharadvaja's head.

But the arhat heard about King Charka's plans. In the scene near the top left corner, as the king approached, Bharadvaja arose from meditation and took six steps to welcome him. As he did, an earthquake struck, terrifying the king, now confronted with the limits of his own power.

Seen near the top center, the king prostrated himself at the latter's feet, confessed his evil intentions, and begged for forgiveness. Pindola Bharadvaja responded explaining, "I can endure your evil intention. It is your mind that you must teach to be forbearing."

Finally, near the top right corner, a nimbate Pindola Bharadvaja is seen residing among his thousand dgra-bcom-pa(arhats) on the Eastern [continent] of Purva-Videha, where, like the other sixteen arhats, he protects Buddhism and awaits to assist the Future Buddha Maitreya. For more information on Pindola Bharadvaja, see Loden Sherab Dagyab,Tibetan Religious Art (2 vols), Wiesbaden, 1977, pp. 102-5.

Lobsang P. Lhalungpa was born in Lhasa, Tibet. From 1940 to 1952, he was a monk-official in the service of the Tibetan government. Brought up in an intensely religious home the son of a one-time State Oracle of Tibet Lhalungpa took Buddhist teachings from several adepts including a female reincarnate. Having been a star pupil, he was sent to India by the Government of Tibet in 1947 to oversee the Tibetan language & Buddhist instruction of the many young Tibetans from nobility sent to study at North Point, a well-established Jesuit school in Darjeeling. In 1956, the External Services of All India Radio recruited him to establish the first Tibetan-language program from New Delhi, which he managed until 1971.

In 1959, Lhalungpha announced His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama's exile from Tibet, which inspired the exodus of Tibetan refugees to India. He then threw himself into relief work. He was one of a three-person team to develop the first modern Tibetan language primers for the newly established schools for Tibetan refugees. Greatly influenced by Mahatma Gandhi, he authored one of the first books on the Life of Gandhi in Tibetan.

Lhalungpha dedicated his life to the promotion and preservation of Tibet's rich spiritual and cultural traditions. In 1948, with George Roerich, he co-authored one of the first books on Tibetan grammar. Later, he went on to translate The Life of Milarepa, and was requested by His Holiness the Sixteenth Karmapa to translate Mahamudra: The Moonlight. He also authored Tibet: The Sacred Realm and many articles for Buddhist journals, and contributed to the landmark Tibetan Art publication, Tibet: Tradition and Change. In his later years, he lived in New Mexico where he was nominated a Santa Fe Living Treasure before his death in 2008.

Lhalungpa collected his thangkas as part of his lifelong Buddhist practice. A few came from his home in Lhasa before 1947. The rest were acquired in India between 1956 and 1971, often as gifts, as part of his ongoing work to preserve Tibetan culture.

As a leading seller of Himalayan art and a committed supporter of the Nepalese culture, Bonhams has announced a section within the sale devoted to raising funds for Nepal following the recent devastating earthquakes. The Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust and Save the Children (both registered 501(c)(3) charities) will receive an equal share of the full hammer proceeds from this section and a donation from Bonhams.

Mark Rasmussen, Specialist / Head of Sale in Indian, Himalayan and Southeast Asian Art at Bonhams in New York said, “This sale comprises another tight grouping of works, selected for their quality, that particularly appeal to buoyant markets today. At the core is a varied group of Himalayan sculptures attesting to highpoints in the history of the Himalayas and surrounding regions. We’re also honored to be raising funds for Save the Children and the Kathmandu Valley Preservation Trust. As media attention naturally shifts to newer tragedies, we hope the needs of the people will not fade from public consciousness, and we are keen to support those committed to the relief and rebuilding of Nepal.”

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F29%2F91%2F119589%2F129030767_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F05%2F67%2F119589%2F127991567_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F18%2F91%2F119589%2F126579416_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F38%2F60%2F119589%2F122319137_o.jpeg)