"Precious as the Morning Star: 12th-14th Century Celadons in the Qing Court Collection" at National Palace Museum, Taipei

Precious as the Morning Star: 12th-14th Century Celadons in the Qing Court Collection. © National Palace Museum.

TAIPEI - "Precious as the morning star" comes from poetry by the Qianlong Emperor in the 18th century. Both "Precious and few as morning stars" and "The morning star truly is precious" are lines that compare something rare and treasured to the fleeting and infrequent phenomenon of a morning star. Qianlong's line for "Viewing Guan (Official) wares of the Zhao-Song dynasty as morning stars" clearly indicates that he valued specifically Song Guan porcelains as precious treasures.

Judging from historical records, so-called "Official kilns" of the Song dynasty refer to sites producing porcelains for the court in the Northern Song and those in the Southern Song at Xiuneisi and Jiaotanxia. In more recent times, the exploration and study of Southern Song Official kilns trace back to the 1930s with evidence gathered and fieldwork by Chinese and Japanese scholars. Though Southern Song Official kilns could not be clearly distinguished at the time, the appreciation for celadons they produced and the issue of solving related questions continued until now. In particular with the discovery of the Laohudong kiln site in Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, many scholars have come to recognize that it and Jiaotanxia as indeed where official wares were fired in the Southern Song. In comparison, our understanding of Northern Song official kiln sites has not only progressed along lines revealed by textual analysis but also by researching imperial poetry from the Qianlong Emperor and excavations at the Qingliang Temple site in Baofeng County, Henan Province. In doing so, the Ru kilns have become considered as possible sites for the Northern Song kilns.

The National Palace Museum has in its collection a large number of celadon porcelains from the former Qing court, and even the places where many of them were stored can be traced. Furthermore, based on the imperial poetry on some, we can learn more about the ideas that the Qianlong Emperor gained by sifting through texts and about the ideas and categorizing of Guan wares in the eighteenth century. Using the past to view the present, how do we ultimately view these precious works from the ages? This exhibition takes into consideration the question of how to use cultural artifacts to not only trace the history of the Qing court collection but also how to integrate modern viewpoints in art history as a way of reinvigorating our understanding of the places, periods, and related issues behind the production of individual wares. This exhibition is divided into four sections on "Ru Wares and the Northern Song Official Kilns," "Southern Song Official Kilns," "The Crackle of Celadon," and "Connoisseurship and Discovery." It is hoped that bringing together these historical objects, textual records, and archaeological materials will illuminate the background for celadon production in the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, the emotions engendered by their appreciation, and the features of specific works.

Ru Wares and the Northern Song Official Kilns

Ru wares, which stand out prominently in the writings of Song dynasty authors, were fired at kilns located at Qingliang Temple in Baofeng County, Henan Province. The firing and use of Ru celadon are described by Song authors as follows: "They were only offered for imperial selection, and those rejected were permitted to be sold" and "At the time of the old capital (of the Northern Song, Kaifeng), Ding vessels did not enter the Forbidden City, only those of Ru." These citations offer historical testimony that Ru wares were used at the court. Furthermore, Xu Jing in his Illustrated Travels of the Xuanhe Emissary to Goryeo (1124) points out the similarity between Goryeo celadons in what is now Korea and Ru wares. Taken together with samples excavated from the Qingliang Temple kiln site close to Goryeo celadon, there is now also evidence for exchange between the Ru kilns and those outside of China.

"Official kilns" generally refer to sites were ceramics were fired for court use. Official kilns were established in the Northern Song under Emperor Huizong, and textual records refer to them as "official kilns of the capital." However, up to now, concrete proof of their exact site has yet to be found, making it difficult to ascertain anything about their nature. If, though, the similarity between some vessel shapes of Southern Song Official (Guan) wares and Ru porcelains is taken into consideration, then at least from the viewpoint of ceramics fired for official use, Ru wares indeed can be seen as the official wares of the Northern Song.

Dish with celadon glaze, Ru ware, Northern Song dynasty, late 11th- early 12th century. H. 3.2 cm, diam. of mouth 13.1 cm, diam. of base 8.9 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei © National Palace Museum.

Narcissus basin with celadon glaze, Ru ware, Northern Song dynasty, late 11th- early 12th century. H. 6.1 cm, w. of mouth 15.8 x 23.1 cm, w. of base 13 x 19.5 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei © National Palace Museum.

Southern Song Official Kilns

In the waning years of the Northern Song, Jin dynasty armies attacked the capital of Bianjing (modern Kaifeng City, Henan Province) and captured Emperor Emeritus Huizong and Emperor Qinzong, marking the end of the Northern Song. Remnants of the court, however, managed to escape south, later establishing a capital they called Lin'an ("Temporary Peace," modern Hangzhou) in what is known in history as the Southern Song. To reestablish legitimacy and authority, the Southern Song court followed the example of Northern Song institutions, one of which was to establish kilns to fire porcelains. At Xiuneisi, the porcelains were "modeled in refined clay and exceptionally exquisite, their glaze colors translucently lustrous and prized throughout the land." As for those from the Jiatanxia kilns, they were "no match compared to the wares of old." These official porcelains are today called "Southern Song Guan wares."

Archaeological excavations in Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province, led to the discovery of the Jiaotanxia kilns, and the Laohudong kilns were also found in the vicinity of Phoenix Mountain. Following analysis of pieces recovered from the kiln openings at these two sites, one of them probably corresponds to the Jiaotanxia official kiln recorded in texts, while the other is perhaps the Xiuneisi official kiln. These two kilns began operation at different times, but their period for firing porcelains overlapped. Among surviving porcelains from the former Qing court collection now in the National Palace Museum, some indeed accurately reflect the product types seen from pieces recovered at those two kiln sites. However, there are still some examples that defy comparison and are even more refined in terms of quality, suggesting the possibility of another as yet undiscovered Southern Song official kiln site.

Hibiscus-shaped container with celadon glaze, Guan ware, Southern Song dynasty, 12th-13th century. H. 9.3 cm, w. of mouth 16 x 16.9 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei © National Palace Museum.

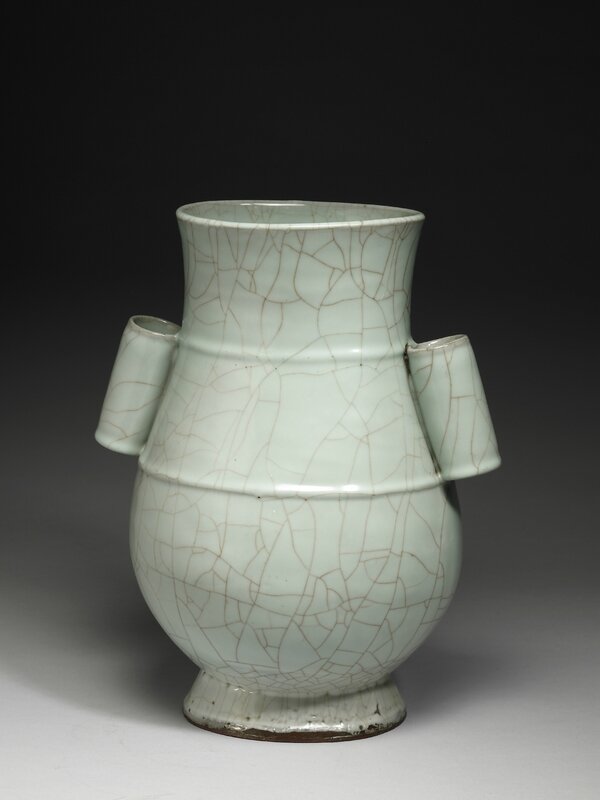

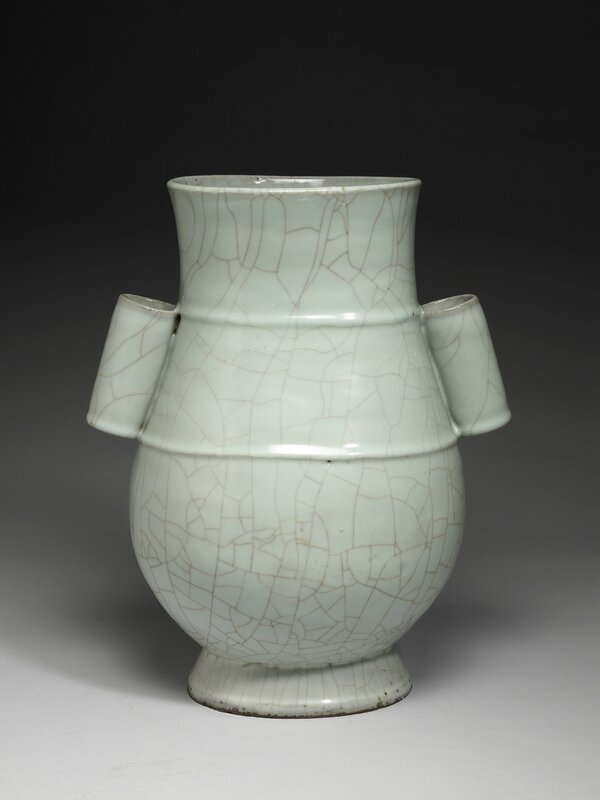

Vase with tubular lug handles in celadon glaze, Guan ware, Southern Song dynasty, 12th-13th century. H. 38.2 cm, w. of mouth 18.3 x 14.2 cm, w. of foot 14 x 16.9 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei © National Palace Museum.

Rectangular basin with celadon glaze, Guan ware, Southern Song dynasty, 12th-13th century. H. 12.5 cm, w. of mouth 20.6 x 28.2 cm, w. of base 19 x 24.9 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei © National Palace Museum.

The Crackle of Celadon

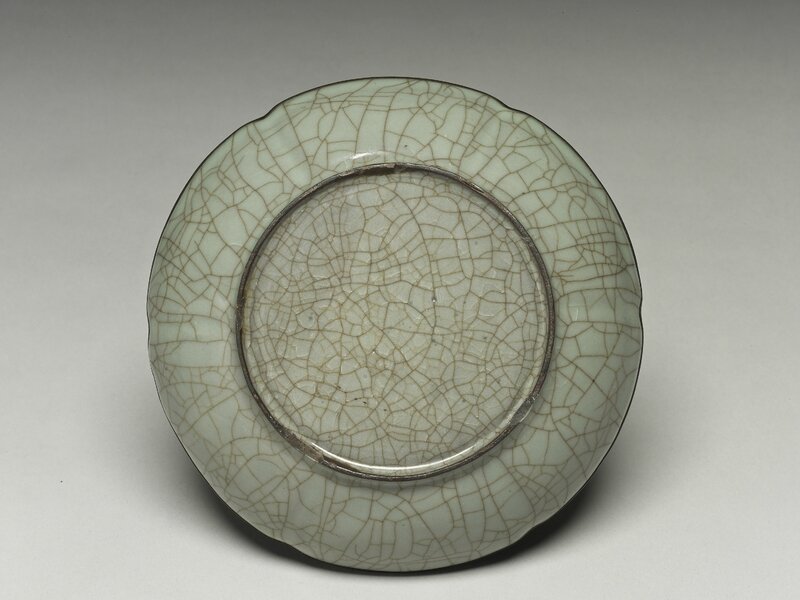

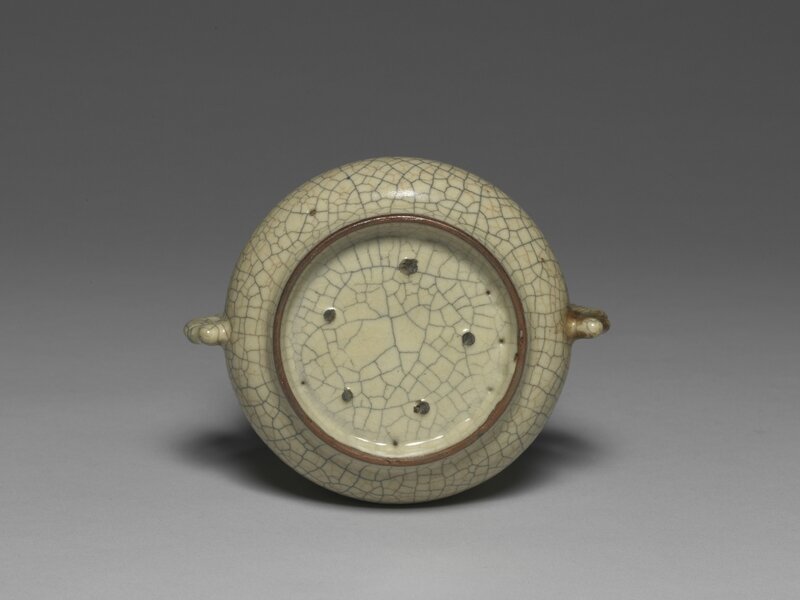

When firing porcelains, the differing rates of expansion and contraction can result in the cracking of the glaze surface, which is known as crackle. Those with crackle are the works mentioned in texts as "cracked pieces," so those with celadon glaze can naturally be called "cracked celadon." The crackle pattern on these works is naturally formed, but staining is sometimes added to highlight it.

Ming dynasty records mention the brothers Zhang, potters in Chuzhou. The elder one's works were called "Older Brother wares" featured crackle patterning. In fact, crackle later became a focus of attention among connoisseurs of the Ming and Qing dynasties, and Gao Lian of the Ming in his Eight Discourses on the Art of Living divided crackle into three types: "eel-blood ice cracks," "plum-blossom-petal dark pattern," and "fine-cracked pattern." And in the Qing dynasty, the Qianlong emperor used the character for "passionate" as a homonym for "cracked" to describe crackled Ge porcelain, singing its praise with the line, "Just like a martyr living up to its name," The crackle of porcelain thus became a metaphor for the passion of a martyr.

As for Ge ware, was it produced at one kiln site or many? Texts mention two sites in Chuzhou (modern Longquan County, Zhejiang Province) and Phoenix Mountain in Hangzhou (modern Hangzhou City, Zhejiang Province). Archaeological evidence also confirms that crackled celadon was fired at the Longquan County large and Xiaomei kilns. And Guan-type celadon from the Yuan dynasty stratum at the Laohudong kiln site also reveals similarities with surviving Ge-ware pieces from the former Qing court collection, leading to the argument that Ge wares were fired at Laohudong.

Brush washer with lotus-petal design in celadon glaze, Guan ware, Southern Song dynasty, 12th-13th century. H. 4.4 cm, diam. of mouth 15.5 cm, diam. of base 9 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei © National Palace Museum.

Dish with dragon design in celadon glaze, Guan ware, Southern Song dynasty, 12th-13th century. H. 4.2 cm, diam. of mouth 18.5 x 18.7 cm, diam. of base 11.5 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei © National Palace Museum.

Floral-shaped brush washer with celadon glaze, Guan ware, Southern Song dynasty, 12th-13th century. H. 4.3 cm, diam. of mouth 17.8 cm, diam. of foot 11.2 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei © National Palace Museum.

Connoisseurship and Discovery

Connoisseurship of porcelain can take the two main approaches: vessel shape and glaze. From the time a form appears to its transformation also involves changes in period style. Likewise, glaze color and decoration can reflect official or market taste.

True celadon was fired as early as the Eastern Han period, but beforehand, kiln ash naturally blanketed ceramics to create a celadon-like glaze, which became known as "gray-glazed pottery" or "proto-celadon." In the eighth and ninth centuries, celadon already was an important type of ceramic for appreciation. Lu Yu of the Tang dynasty, for example, in his Classic of Tea, refers to it as "like jade," and the poet Lu Guimeng of the same period compared it to "a thousand peaks of green color," both singing the praise of celadon through similes. In this exhibition of celadons from the twelfth to fourteenth centuries, various differences in place and period of firing can be discerned, such as the sky-blue glaze of Ru wares, the ice-like crackle on Guan wares, the plum-green hues of Longquan wares, and the cracked pattern on Ge wares.

At the same time, shards collected from kiln sites have also uncovered some of the mysteries lying beneath the celadon surface. Regardless of glaze thickness and evenness, and whether there is decoration or not, these features are worth remembering in connoisseurship and important reference points. In this exhibition, special gratitude is due to the Chang Foundation and the Graduate Institute of Art History at National Taiwan University for providing celadon shards to display with the wares.

Stepped pot with cream-colored celadon glaze, Guan ware, Southern Song dynasty, 12th-13th century. H. 14.4 cm, w. of mouth 9 x 12.5 cm, w. of base 9.3 x 12.4 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei © National Palace Museum.

Bowl with hibiscus-shaped rim in celadon glaze, Longquan ware, Southern Song dynasty, 13th century. H. 7.3 cm, diam. of mouth 17.4 cm, diam. of foot 5.3 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei © National Palace Museum.

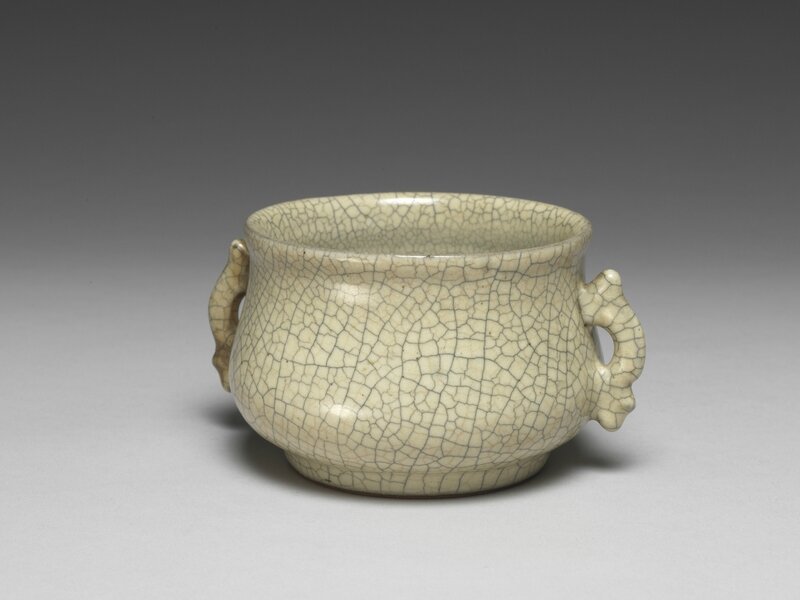

Censer with fish-shaped handles in cream-colored celadon glaze, Yuan dynasty, 14th century. H. 8.2 cm, diam. of mouth 11.5 cm, diam. of foot 8.8 cm. National Palace Museum, Taipei © National Palace Museum.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F63%2F90%2F119589%2F129042528_o.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F28%2F46%2F119589%2F128715587_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F21%2F69%2F119589%2F128475813_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F19%2F09%2F119589%2F126883420_o.jpg)