An exceptional Song figure of Guanyin to be offered in the Asian Art sale Christie’s Paris, december 14

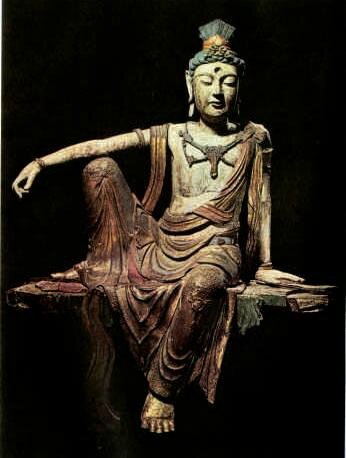

Lot 27. Rare et importante statue de Guanyin en bois polychrome et doré, Chine, dynastie Song (960-1279). Estimate EUR 200,000 - EUR 300,000 (USD 213,717 - USD 320,576). Price realised EUR 5,170,500. © Christie’s Images Limited 2016.

Paris – On December 14, Christie’s Paris will offer its Asian Art sale, the second Parisian auction this year. After a successful 300 lots sale that achieved over €9M, this season’s auction is focused on a smaller amount of works of art, nonetheless important. Each work has been carefully selected to fit the sale, the main focus being beauty, high quality and interesting provenances. On December 14, 88 lots will be offered at a global estimate of 2 to 3 million euros, spanning works from all Asia, with pieces from India, Java, Cambodia, Thailand, Tibet, China and Japan.

The sale is led by an important Song Dynasty wood figure of Guanyin estimated at €200,000-300,000. This important 13th century masterpiece comes from the former collection of Roger Vivier, famous French shoe-maker who invented the stiletto heel and produced shoes notably for Dior. Additionally, the sculpture was exhibited in 1954 in Paris at the musée des Arts Décoratifs, and has been featured in numerous publications.

Lot 27. Rare et importante statue de Guanyin en bois polychrome et doré, Chine, dynastie Song (960-1279). Estimate EUR 200,000 - EUR 300,000 (USD 213,717 - USD 320,576). Price realised EUR 5,170,500. © Christie’s Images Limited 2016.

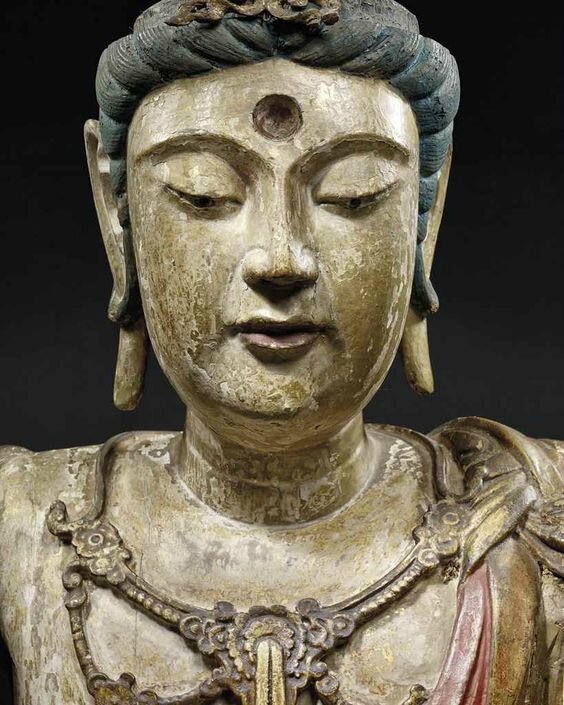

A rare and important gilt and polychrome wood figure of Guanyin, China, Song dynasty (960-1279)

Il est élégamment assis en rajalilasana, la main droite posée sur son genou droit plié. Il est vêtu d'un fin dhoti, une écharpe posée sur ses épaules laissant son torse dénudé paré d'un précieux collier. Son visage aux yeux mi-clos est empreint de sérénité et surmonté d'un haut chignon retenu par un ruban rouge. Son front est agrémenté de l'urna ; restaurations. Hauteur : 131 cm. (51 ½ in.), socle

Provenance: Compagnie de la Chine et des Indes, Paris.

Collection of Mr Roger Vivier (1903-1998), Paris. Mr Vivier was a famous French fashion designer who specialised in shoes. His best known creation was the stiletto heel. He was called the "Fragonard of the shoe" and worked amongst others for Christian Dior.

Acquired from Mr Vivier by a French private collector through the expert Michel Beurdeley on June 28th 1978, and thence by descent in the family.

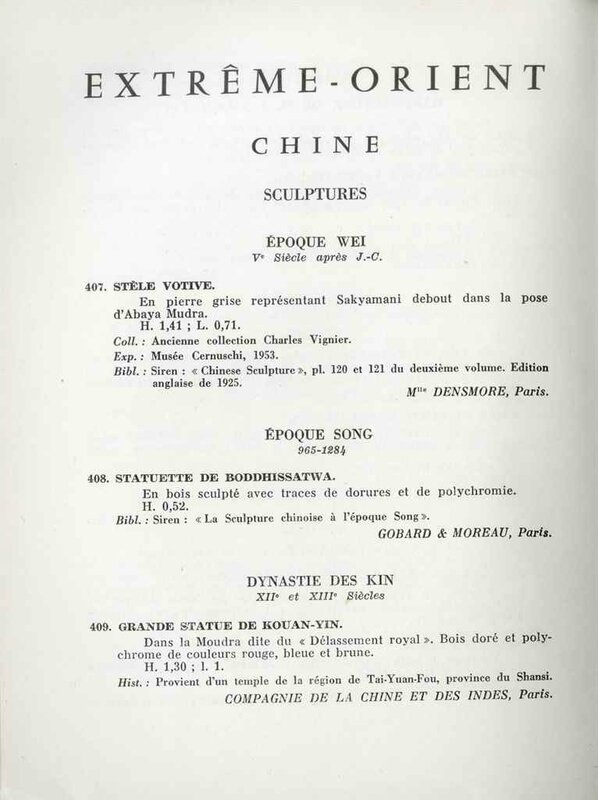

Literature: Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Chefs d'Oeuvre de la Curiosité du Monde, 2ème Exposition Internationale de la C.I.N.O.A, 10 June - 30 September 1954, Exhibition Catalogue, n° 409. (fig. 1a & 1b)

Encyclopaedia Universalis, Encyclopaedia Universalis France S.A, Paris, 1968, Volume 5, article Dieux et Déesses, pl. VI. (fig. 3)

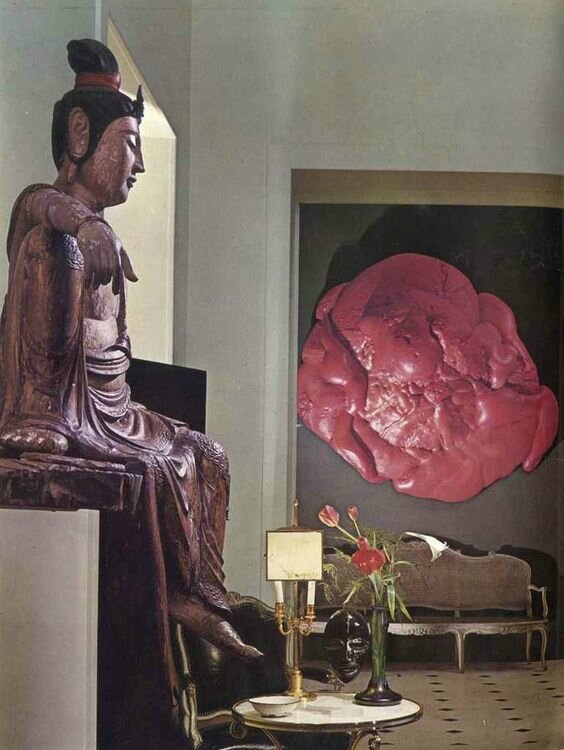

Connaissance des Arts, Les grandes collections, Art ancien avec Art nouveau pour M. Roger Vivier la création artistique ne connait ni frontières ni époques, Juillet-Aout 1968, n° 197-198, pp. 88-94. (fig. 2)

fig. 1a & 1b - Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Chefs d’Oeuvre de la Curiosité du Monde, 2ème Exposition Internationale de la C.I.N.O.A, Paris, 10 June - 30 September 1954, Exhibition Catalogue, n° 409.

fg. 2 - Interior of Roger Vivier's home in Connaissance des Arts, Les grandes collections, Art ancien avec Art nouveau [...], Paris, Juillet-Août 1968, n° 197-198, pp. 88-94.

fg. 3 - Encyclopaedia Universalis, Encyclopaedia Universalis France S.A, Paris, 1968, Volume 5, pl. VI.

Exhibited: Paris, Musée des Arts Décoratifs, Chefs d'Oeuvre de la Curiosité du Monde, 2ème Exposition Internationale de C.I.N.O.A, 10 June - 30 September 1954.

Serenity and Compassion – A Rare Song Dynasty Guanyin

Rosemary Scott, International Academic Director Asian Art

This graceful figure of the bodhisattva Guanyin sits in a variation of the pose known in Indian iconography as rajalilasana, or ‘royal ease’. The left leg is pendant, while the right is bent and raised, so that, at just below shoulder height, the bodhisattva’s right arm is able to rest casually on the knee. The torso leans very slightly to the left, giving the impression that the left arm, which is straight, appears to take the full weight of the body. The figure does, indeed, appear completely at ease – relaxed, but retaining a quiet dignity and serenity. This pose is often associated with one of the most popular aspects of the bodhisattva – ‘Guanyin of the Southern Seas’ or ‘Water-Moon Guanyin’. This name is a reference to Guanyin residing on the mythical Mount Potalaka, which was believed to exist in the seas off the southern coast of India. This particular imagery was introduced into China in the 5th century with the first complete translation of the Avatamska Sutra (full name - Mahavaipulya Buddhavata?saka Sutra, The Flower Adornment Sutra 大方廣佛華嚴經), one of the most influential sutras of Mahayanist Buddhism.

The bodhisattva Guanyin, whose name in Sanskrit is Avalokitesvara, is an important fgure in the Mahayanist Buddhist tradition. The Sanskrit name derives from two parts – avalokita, meaning ‘seen’ – and ishvara, meaning ‘lord’. The meaning is therefore either ‘the lord who is seen’ or ‘the lord who sees’. In either case it is the presence of the deity amongst the people of the world, and his accessibility, that is emphasised. The full name in Chinese is Guanshiyin 觀世音 – ‘one who hears the sounds [prayers] of the world’. The impression is of an omnipresent deity to whom mortals may turn in times of trouble. Guanyin is a bodhisattva, which means that he is one who has attained enlightenment, but who has deferred entering nirvana and Buddhahood in order to help allay the sufering of others and help them to attain enlightenment. In the Chinese translation of the Saddharma Pundarīka Sutra (Lotus Sutra 妙法蓮華經), the Indo-Iranian Kumarajiva (ca. AD 350-410) refers to Guanyin as the ‘Bodhisattva of Infnite Compassion’. With the rise of the Pure Land School of Buddhism in China in the 7th century, Guanyin became one of the most prominent figures in the Chinese Buddhist pantheon. In the Song dynasty, when this sculpture was created, Guanyin was still depicted as an androgynous male, but later in the 12th century the bodhisattva began to be associated with a female manifestation, which gained momentum in the succeeding centuries until Guanyin was seen as the ‘Goddess of mercy’.

In Pure Land Buddhism 淨土宗 Guanyin is identifed as one of the counsellor-emissaries of the Buddha Amitabha – the Buddha who presides over the Pure Land or Western Paradise, and in a second translation of the three sutras that comprise the Pure Land Sutra, Guanyin is identifed as the successor to Amitabha. The same translation notes that any virtuous man or woman who fnds themselves in trouble may entrust themselves to the Bodhisattvas Avalokitesvara or Mathasthamapraptra, and they will be saved. Representations of Guanyin, therefore, may sometimes be identifed by a small figure of Amitabha at the front of the diadem.

This bodhisattva is shown in simple, but princely robes. The lower body and legs are clothed in a paridhana or long dhoti, which falls in elegant, natural, folds and conforms to the shape of the lower legs of the figure. His chest is bare, but a long sinuous scarf crosses it obliquely, is tied on the left shoulder, and is draped over the right arm. The bodhisattva wears jewellery appropriate to his princely rank in the form of a necklace, bracelets, and a diadem in his hair. Typically for figures of this period, the hair is looped around the ears and then swept up into a chignon. Like a number of other surviving wooden bodhisattva figures of this date there are relief designs on the paridhana at the knees of the figure and along the edges of the cloth. It must be born in mind that figures such as this one would have been in a temple for centuries and at intervals it would have been redecorated. Therefore, not only are there several layers of pigment, but these relief designs, which may have been added in the Ming dynasty.

A slightly larger Northern Song Guanyin sculpture in this pose, although seated on a lotus throne, dated to the third year of Yuanfeng (AD 1079), is in the Chongqing temple in Shanxi province (illustrated in Zhongguo meishu quanji, diaosu bian, 5, Wudai Song diaosu, Beijing, 1988, p. 65, no. 64. Such sculptures, including the current example are particularly associated with North China, especially Shanxi province in the period 10th-14th century, due to the pre-eminent centres of Buddhism at Taiyuan and Wutaishan. Another similar figure, dated c. AD 1025, is in the Honolulu Academy of Arts. A slightly smaller Guanyin in this pose, dated c. AD 1200, is in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London and is discussed at length by J. Larson and R. Kerr in Guanyin –A Masterpiece Revealed, London, 1985. A slightly smaller figure of Guanyin in similar pose, dated c. AD 1250, is in the collection of Princeton University, where the curators note that the relief decoration on the skirt and scarves of the figure was probably added during the Ming dynasty. A slightly larger Song sculpture of Guanyin in this pose is also in the collection of the British Museum, London (see Buddhism: Art and Faith, London, 1985, no. 296), while a slightly smaller Northern Song figure of the bodhisattva Manjusri in a similar pose, is in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum (see Wisdom Embodied – Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 2010, p. 180, no. A44).

Guanyin (Bodhisattva), c. 1025. Painted wood, height: 67 in. (170.2 cm). Purchase, 1927 (2400) ©2014 Honolulu Museum of Art.

Figure of Bodhisattva Guanyin, wood, carved, painted, lacquered and gilded, China, Jin Dynasty, ca. 1200. Purchased with the assistance of The Art Fund, the Vallentin Bequest, Sir Percival David and the Universities China Committee (A.7-1935) © Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2016.

Guanyin seated in Royal-ease pose, ca. 1250, Southern Song dynasty, 1127–1279. Wood with traces of blue-green, red, and gold pigments on white clay underlayer with relief designs. h. 110.0 cm., approx w. 79.0 cm., approx d. 50.0 cm. (43 5/16 x 31 1/8 x 19 11/16 in.). Museum purchase, Carl Otto von Kienbusch Jr., Memorial Collection (y1950-66) © 2016 The Trustees of Princeton University

Wooden figure of Avalokiteshvara, 11thC-12thC. Purchased with the assistance of The Art Fund Asia 1920,0615.1 © The Trustees of the British Museum

Bodhisattva Manjushri (Wenshu), late 10th-early 12th century. © 2000–2016 The Metropolitan Museum of Art

A C14 test (CIO/853-16/PWL, Rijksuniversiteit Groningen) dated 20 June 2016, consistent with our dating, is available on request.

FURTHER HIGHLIGHTS OF THE SALE INCLUDE:

Lot 53. Rare statue du bouddha Vairocana en bronze doré, Chine, dynastie Liao, XIème siècle. Estimate EUR 150,000 - EUR 200,000 (USD 160,288 - USD 213,717). Price realised EUR 13,570,500. © Christie’s Images Limited 2016.

An important gilt-bronze figure of Buddha Vairocana, China, lLao dynasty, 11th century

Il est représenté assis sur une base lotiforme, les mains en jnanamudra, vêtu de robes monastiques et paré de bijoux. Le visage serein est surmonté d'une haute tiare abritant une image de bouddha. Une inscription incisée zuo xun yuan yan ji guan jian (marque officielle de contrôle) à la base ; petite restauration à l'étole. Hauteur : 24 cm. (9 ½ in.)

Provenance: Acquired in 1941 by Mr Bisseling, The Hague and thence by descent.

Private Dutch collection.

An inventory card made by Mr Bisseling in 1941.

Literature: H. A. van Oort, The Iconography of Chinese Buddhism in Traditional China, volume II: Sung to Ch'ing, Leiden, E. J. Brill, 1986, p. 23, plate XXXV.

Notes: This exceptional gilt-bronze figure of Vairocana illustrates the five Tathagatas in his highly ornate cylindrical crown. This seems to be a unique iconographic feature found amongst the small group of comparable elite bronzes cast under the patronage of the rulers of the Liao dynasty (907-1125). This known group of bronzes all demonstrate a comparable style: the figure itself is dignified and serene, the gilding is fine, and they wear lavish adornments and drapery. The style derives from late Tang dynasty (618-907) iconography. The known group shares a specific type of lotus base that can be divided into two different shapes. One cast with an integral lotus base supported by cabriole legs and the other with the lotus pericarp directly placed on a low drum-shaped base, like the current one.

The inside of this bronze Vairocana’s base is incised with an inscription mentioning that the bronze was registered at a local government office. It is known from research that bronze as a material was rare and costly in these days. Therefore, bronze objects were exclusive and had to be registered before being brought on the market. Perhaps its importance and particularly heavy weight required this official government approval.

Most of the known bronze examples represent bodhisattvas and only but a few would depict a Buddha form. Most of the latter kind represent Buddha Amitabha. Only one other Vairocana example, though it was described as a bodhisattva, seems to be known and was published by A & J Speelman Ltd., International Asian Art Fair [catalogue], New York, 1998, p. 76. In 2006, that bronze was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of New York (accession number 2006.284) who identified it correctly as Vairocana, based on the specific hand gesture. This esoteric ‘mudra of knowledge’ (janamudra) or ‘diamond fist’ (vajramudra) symbolises the combination of opposites, male and female, yin and yang, as well as wisdom and compassion. However, that bronze figure does not bear the five Tathagatas in his crown like the current example.

Vairocana is the Primordial Buddha from whom all things emanate. He heads the group of five Tathagatas or cosmic Buddhas, each representing a different mood, colour and direction. The teachings of the transcendent Buddhas were relatively popular in China from the Tang up to the Liao period based on various stone and clay examples that have come down to us.

This small group of luxurious commissions for Liao Buddhist shrines can be dated to the eleventh century, based on a group of over life-size clay figures in the Lower Huayan Temple, Datong, Shanxi Province, dated to 1038 AD. The temple was then located in the western capital of the Liao kingdom. Angela Falco Howard (et al.) published a picture of the shrine in her magnum opus Chinese Sculpture, Yale University Press, New Haven, 2006, p. 375, figure 4.18. Bodhisattvas of this shrine share the same proportions, ornaments, clothes and high crowns along with several of their gilt-bronze counterparts, including the current one. Other gilt-bronze Liao examples in public institutions are cited in the catalogue note of Lot 396, Christie’s, New York, 19 March 2008. However none of these cited comparable gilt-bronze Buddhist figures match the quality, rarity and iconographic complexity of this superbly cast sacred image.

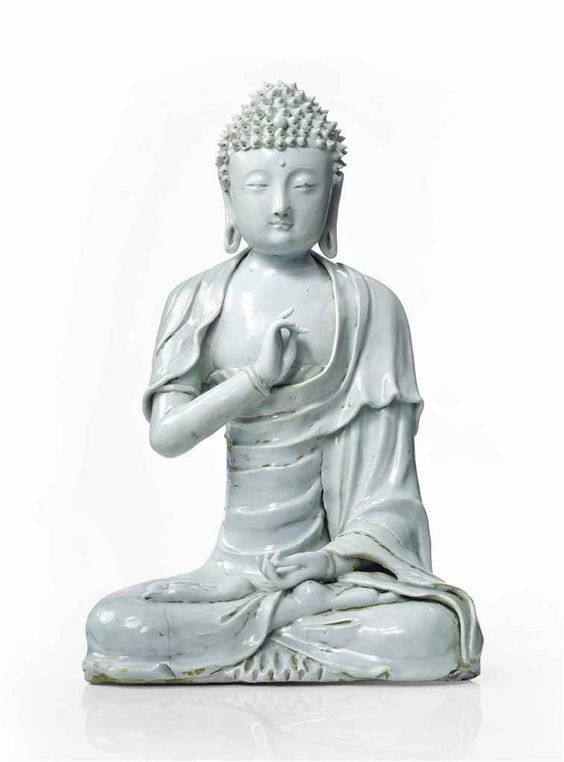

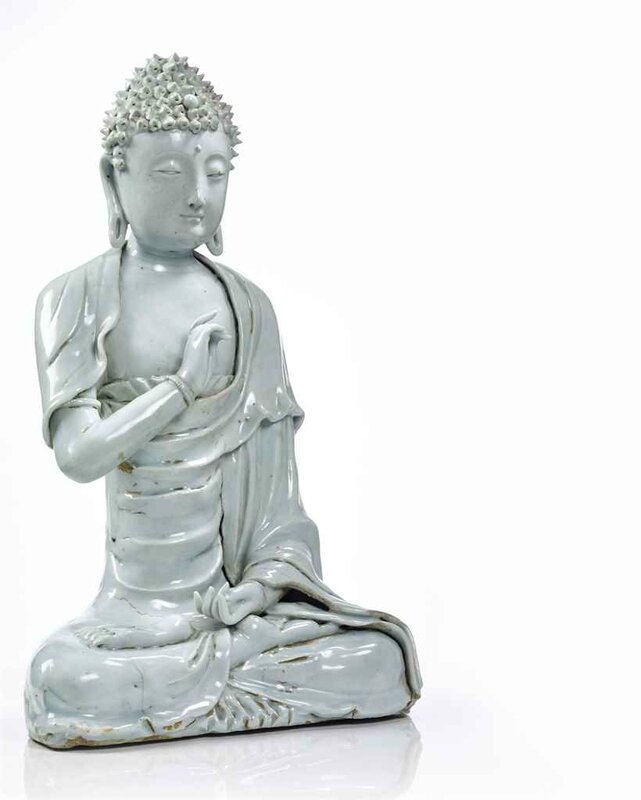

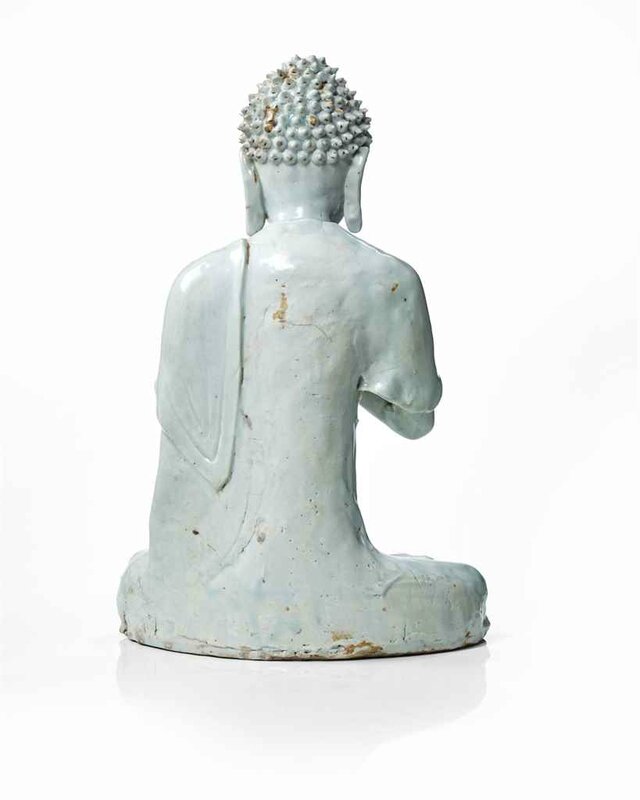

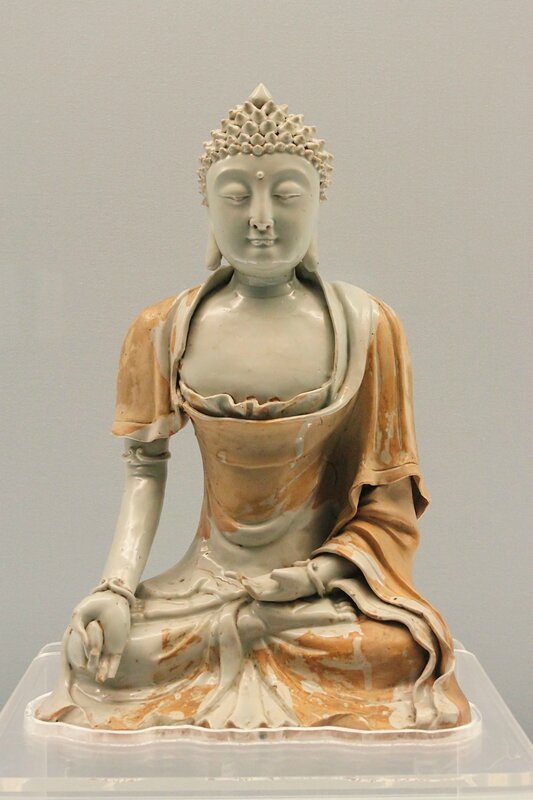

Lot 50. Rare et importante statue de bouddha Shakyamuni en porcelaine qingbai, Chine, dynastie Yuan (1279-1368). Estimate EUR 150,000 - EUR 200,000 (USD 160,288 - USD 213,717). Price realised EUR 842,500 © Christie’s Images Limited 2016.

A very rare and important qingbai figure of Buddha Shakyamuni, China, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368)

Il est représenté assis en padmasana, la main droite en vitarkamudra et la main gauche en gyanmudra. Le buste exagérément allongé du bouddha est vêtu d'une robe monastique plissée et drapée sur ses épaules couvrant ses bras parés de bracelets. Son visage est méditatif, le front portant l'urna, les yeux mi-clos sous les arcades sourcilières arrondies et les lobes d'oreilles allongés. Ses cheveux bouclés surmontés de l'ushnisha et ornés du ratna. La statue est recouverte d'une délicate glaçure blanc bleuté ; restaurations. Hauteur : 37 cm. (14 ½ in.), socle

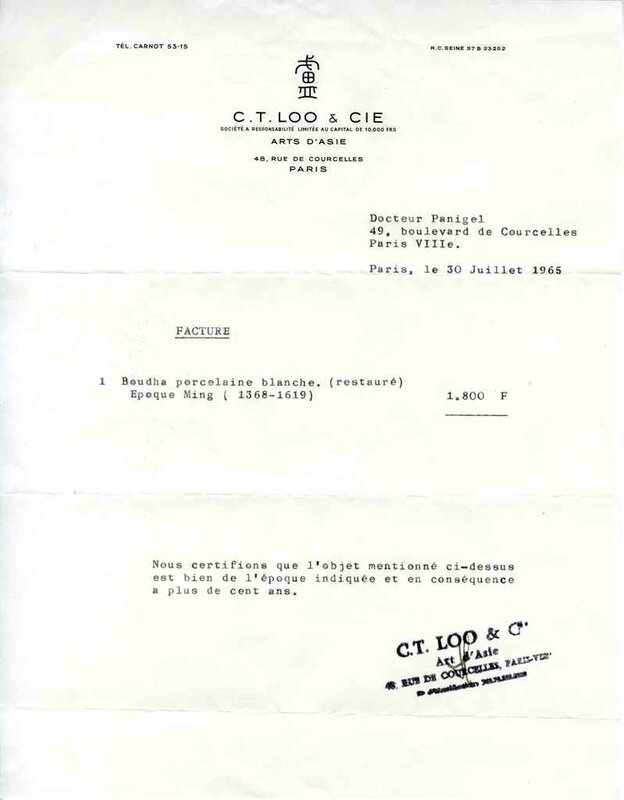

Provenance: With Galerie C.T. Loo & Cie, Paris, 30 July 1965.

Private French collection.

1965 invoice from C.T. Loo & Cie.

A Rare Yuan Dynasty Qingbai-glazed Seated Buddha

Rosemary Scott, International Academic Director Asian Art

This slender figure sits in padmasana (also known as the lotus position) with each foot resting on the opposite knee, sole upwards. The Buddha’s back is straight, and his right hand is held in front of his chest in the vitarka mudra, which symbolises intellectual discussion, while the ring formed by the forefinger and thumb signifies the wheel of law. The Buddha’s left hand rest gently in his lap in the gyan mudra, which is sometimes called the mudra of knowledge. In accordance with the 32 lakshanas (special bodily features of the Buddha), the figure has an urnain the centre of his forehead (symbolising spiritual insight), and an usnisha on the top of his head (symbolising the attainment of enlightenment). He also has elongated ear-lobes, which reflect the fact that the Buddha was formerly a prince, who wore heavy jewellery.

While there are a number of Yuan dynasty qingbai-glazed Bodhisattva figures known, usually depicting Guanyin, Buddha figures are much rarer. Yuan dynasty Buddhist figures made in porcelain and covered with a qingbai glaze, developed from the tradition of finely-modelled religious figures made at the Jingdezhen kilns during the Southern Song period (1127-1279). There is a very small extant group of these Song figures in international collections. Inscriptions and the date of tombs in which these figures have been found suggest that they were made in the second and third quarters of the 13th century - just prior to the Mongol conquest. The majority of the extant Song dynasty figures of this type have been discovered in the south of China, within territory controlled by the Southern Song, however at least one has been found in the north, in Jin dynasty (1115-1234) territory, and suggests that the figure was regarded as valuable enough to warrant being taken hundreds of miles into lands controlled by the Jurchen.

All the qingbai religious figures surviving from the Southern Song dynasty appear to be only partly glazed, to allow for the application of ‘cold-painted’ decoration, but this was not usually the case in the Yuan dynasty, when the figures are generally fully glazed, as in the case of the current figure. However, there is a small number of Yuan dynasty partially-glazed qingbai Buddhist figures, where the unglazed areas were intended to be covered with lacquer. This can be seen on a seated, qingbai glazed, figure of the Buddha Amitabha is in the collection of the Beijing Art Museum (exhibited by Christie’s New York in Treasures from Ancient Beijing, 2000, exhibit no. 7). This figure, dated to the Yuan dynasty, has robes, which are partially lacquered, apparently over areas of the porcelain left free of glaze. Gilded designs, representing the patterns on the robe are painted on the lacquered areas. The partial glazing of a Yuan dynasty seated qingbai Buddha (fig. 1) in the collection of the Shanghai Museum (illustrated in Qingbai Ware: Chinese porcelain of the Song and Yuan Dynasties, S. Pierson (ed.), London, 2002, pp. 208-9, no. 117), suggests that it too would originally have had lacquer applied to the unglazed parts of its robe. The lacquer seems to have adhered rather tenuously to the porcelain and was very susceptible to damage, which would explain why none can now be seen on the Shanghai figure. These figures are 51 cm. and 41.3 cm. in height, respectively - somewhat larger than the current figure. A Yuan dynasty seated Guanyin (fig. 2) in the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City, dated by inscription to AD 1298 or 1299, is 51.4 cm. tall, and is fully glazed except for the figure's underskirt, which has been left unglazed, possibly to allow for the application of lacquer (illustrated by S.E. Lee and Ho Wai-kam, Chinese Art Under the Mongols: The Yüan Dynasty (1279-1368), Cleveland, Ohio, 1968, no. 26).

fig. 1 - Qingbai glazed buddha statue, Jingdezhen ware, Yuan dynasty, 1271-1368 A.D., Shanghai Museum.

fig.2 - Guanyin Bodhisattva, ca. 1298, Chinese, Ying-ch’ing ware (glazed porcelain), 20 1/4 x 12 x 7 3/4 inches (51.44 x 30.48 x 19.69 cm). Purchase: William Rockhill Nelson Trust. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City.

The Yuan dynasty porcelain figures with qingbai glaze are frequently larger than their Southern Song counterparts. The famous qingbai glazed Yuan dynasty Bodhisattva seated in Maharaja lilasana (fig. 3), which was excavated in 1955 from Dingfu Street in the western suburbs of Beijing, is 67 cm. tall. This figure is now in the Capital Museum, Beijing (illustrated in Complete Collection of Ceramic Art Unearthed in China –1 – Beijing, Beijing, 2008, no. 81). Another qingbai glazed seated Bodhisattva in the collection of the Rietberg Museum, Zurich, is 52 cm. in height (illustrated by S.E. Lee and Ho Wai-kam, op. cit., no. 25), and the Yuan dynasty qingbai glazed seated bodhisattva (fig. 4) in the Metropolitan Museum, New York is 50.8 cm. tall (illustrated by S. Pierson, op. cit., pp. 218-9, no. 122). A bodhisattva in the collection of Mr. Alan Chuang, which is notable for its particularly fine jewellery and also its size, is 67 cm. high. The appearance of larger figures in the Yuan dynasty towards the end of the 13th century can be explained not only by changing tastes, but also by changes in technology - specifically to the porcelain body material used at Jingdezhen. The new body material contained more kaolin and thus more alumina, which facilitated the production of larger figures, and indeed vessels.

fig. 3 - Qingbai porcelain statue of the Buddha, Guan Yin, Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368 AD), Capital Museum, Beijing.

fig. 4 - Bodhisattva, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), 14th century. Glazed porcelain (Qingbai ware). H. 20 in. (50.8 cm); W. 12 in. (30.5 cm); D. 8 in. (20.3 cm). Gift of Edgar Bromberger, in memory of his mother, Augusta Bromberger, 1951 (51.166) © 2000–2016 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

However a number of extant Yuan dynasty figures, including the current figure, fall into a size group which falls somewhere between the smaller Southern Song figures and the very large Yuan figures. A elaborately bejewelled Yuan dynasty Guanyin in the collection of C.P. Lin (illustrated by R. Scott in Elegant Form and Harmonious Decoration: Four Dynasties of Jingdezhen Porcelain, London, 1992, p. 20, no. 4) is slightly smaller than the current figure, as is a Yuan Guanyin (fig. 5) in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum (illustrated by S. Pierson, op. cit., pp. 216-7, no. 121). A seated qingbai figure of Guanyin (fig. 6) sold by Christie’s Hong Kong, 26 November, 2014, lot 3102, also belongs to this group, the sizes of which range from 30 cm. to 38 cm. While the majority of the very large Yuan dynasty porcelain figures have open bases, a number of this smaller group have closed bases – as in the case of the current Buddha figure. The current figure may also be compared with another Yuan dynasty, fully-glazed, seated Buddha, exhibited in Hong Kong by the Oriental Ceramic Society and the Fung Ping Shan Museum in Jingdezhen Wares – The Yuan Evolution, 1984, no. 24. The exhibited figure shares a number of similar features, especially the drapery and the treatment of the hair, but the right hand is held in a different mudra, and it is slightly smaller than the current seated Buddha.

fig.5 - Figure of Guanyin, porcelain with qingbai glaze, China, Yuan dynasty, 1279-1368. Height: 26.7 cm. C.30-1968 © Victoria and Albert Museum, London 2016

fig. 6 - An exceedingly rare Qingbai seated figure of a bodhisattva, Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) sold HKD 6,040,000 (USD 782,520) at Christie’s Hong Kong, 26 November 2014, lot 3102. © Christie’s Images Limited 2016.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240423%2Fob_b6c4a6_telechargement.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240414%2Fob_fc4708_2024-nyr-22642-0956-000-a-dehua-figure.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240413%2Fob_120396_2024-nyr-22642-0941-001-an-exceptional.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240324%2Fob_0e02d1_181-1.jpg)