Museum Rietberg Zurich showing comprehensive exhibition on the Nasca culture

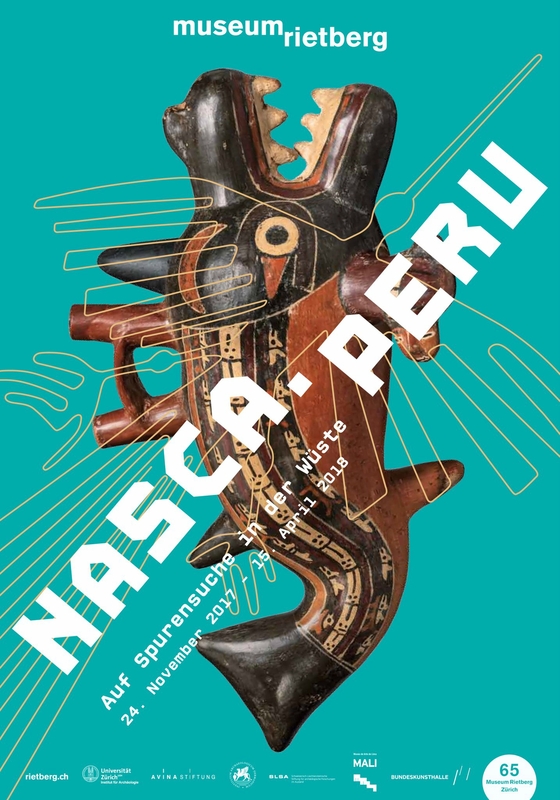

Poster of the exhibition.

ZURICH.- Probably the most comprehensive exhibition on the fascinating as well as mysterious Nasca culture ever to be seen in Europe is on view at the Museum Rietberg Zurich. Nasca. Peru – Searching for Traces in the Desert whisks visitors away to the southern part of the Andes where the Nasca culture (ca. ca. 200 BC – AD 650) once flourished. On the desert ground of this region in Peru the Nasca left behind one of the greatest puzzles ever encountered by archaeologists: large geoglyphs, better known as the Nasca Lines.

Recent archaeological findings tell of a lost culture full of mysterious rituals, but also of a vibrant tradition of art and music and of a life under extreme conditions in one the most arid places on earth. On show are ceramic vessels bearing enigmatic drawings, gold masks, musical instruments, and colourful textiles. All the exhibits are from Peruvian collections, many of them on international display for the first time.

Hanger handle double spout in the form of an orca (killer whale). Clay, modeled and painted, burned, Early Nasca period, 50-300 AD © Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú; Ministerio de Cultura del Perú.

The show is a collaboration between Museo de Arte de Lima and the Museum Rietberg, in cooperation with the Kunst- und Ausstellungshalle der Bundesrepublik Deutschland, Bonn, and involving the participation of leading Nacca archaeologists from across the world. The show is supported by the SchweizerischLichtensteinische Stiftung für archäologische Forschungen im Ausland (SLSA), the Kommission für Archäologie Aussereuropäischer Kulturen (KAAK, Bonn) of the German Archaeological Institute (DAI), and the AVINA Foundation. NASCA. PERU – Searching for Traces in the Desert is curated by Cecilia Pardo, curator of collections at Museo de Arte de Lima, and Peter Fux, curator for America at Museum Rietberg, who has first-hand knowledge of the Nasca region from the archaeological excavations he conducted there.

Who were the Nasca? How did they live? Where did the Nasca culture come from, where did it go? The exhibition attempts to describe the Nasca culture as extensively and detailed as possible, including its social system, its history and above all its art. The approximately two hundred exhibits have an exciting story to tell about everyday life in the fertile valleys between the high ranges of the Andes in the east and the desert off the Pacific coast. It is here, in one of the most arid places on earth, that the Nasca created their famous geoglyphs. Equally fascinating is the immensely colourful pictorial language they used to decorate their ceramics and textiles. A captivating array of musical instruments, colourful cloths, and valuable grave goods including gold masks and ceramic vessels bearing vibrant and enigmatic designs await visitors to the show.

All the exhibits are from Peruvian collections and museums, some of them from recent archaeological excavations.

Cloak with colored, interlocking step triangles and embroidery ribbons. Canvas fabrics. Initial Nasca Phase, 200 BC Chr. - 50 AD, Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú; Ministerio de Cultura del Perú © Daniel Giannoni. Archi, Archivo Digital de Arte Peruano.

Nasca Adventure

For archaeologists as well as for visitors to the exhibition, the Nasca culture holds a very special adventure. After the first human groups arrived in America – probably between 18,000 and 14,000 BC when the Asian and American continents were still connected by a land bridge across the Bering Strait (the water still being locked in the glaziers during the ice age) – many new cultures evolved in America independently of the cultures of Eurasia. The Nasca represent a very special and interesting case: they had no system of writing in the modern sense of the term but relied instead on a rich pictorial language, which they applied to their ceramics and textiles and, above all, to the desert ground in the form of geoglyphs. Over the course of the centuries they developed a highly complex culture with a ritual system which, in many ways, appears alien to us but also with one of the most elaborate art traditions known to the archaeological world. There is probably no pre-Hispanic culture with a more vibrant and colourful tradition of ceramics and textiles than the Nasca, which ranks among the world’s most artistic.

Textile fragment with flying priest beings. Cotton plain weave, embroidered with dyed camelid wool, initial Nasca phase, 200 BC BC - 50 AD © Museo de Arte de Lima, estate of the Prado family.

The Geoglyphs

The geoglyphs of the Nasca Plateau on Peru’s southern coast are among the most extraordinary preHispanic legacies. Covering an area of more than 500 square kilometres the stony desert floor between the valleys at the foot of the Andes was transformed by way of extensive earth drawings cut into the ground of the plateaus, the so-called pampas, as well as the adjacent slopes and hills. Today these drawings are referred to as geoglyphs, literally “earth carvings”. Where the markings have not been destroyed by humans, they have survived to this day owing to the favourable climatic conditions. No one knows exactly how many geoglyphs the Nasca Plateau holds; their number goes into the thousands. One small group has attracted special attention because it features clearly recognizable animals (among others, hummingbird, pelican, monkey, dog, spider, lizard, and whale) and human-like figures. Today these figurative geoglyphs are among the main tourist attractions in the area, with tour operators from the nearby town of Nasca offering sightseeing flights over the pampas. More numerous are the geometrical geoglyphs; they vary in complexity from simple lines to bounded shapes. Some of them are huge; the largest trapezoid measures 1.9 kilometres in length.

The desert plateaus situated between the fertile valleys, where humans dwell, and the mountain ranges, where the gods reside, form a kind of intermediate zone, an ideal place for establishing contact with supernatural forces. It represents a ritual space, and it is here where one finds the geoglyphs. Based on archaeological research, scholars are today convinced that the earth drawings were not made for looking at, but for pacing off. People moved along them, in other words, the images served as ritual paths. They performed the rituals to music – no other Andean culture left behind more musical instruments than the Nasca – and with the aid of psychoactive substances. The drawings’ geometrical forms helped to create a rhythmic experience.

Cups in head shape with headdress and face painting. Clay, modeled and painted, fired, Middle Nasca Period, 300-450 AD, Private Collection, Lima. © Daniel Giannoni

Nasca 2.0

Apart from the exhibits, the show presents the desert landscape in form of projections on to large, relief-style terrain models. The geoglyphs were recorded especially for the exhibition with the aid of drones. The result is a set of highly impressive images. Visitors can “fly over” the landscape using special 3D glasses, thus getting the same view of the geoglyphs as an ancient Nasca priest with the aid of his inner eye.

November 24, 2017 - April 15, 2018

Figurine of a mythical ancestors being. Clay, modeled and painted, burned, Early Nasca phase (style phase Nasca 3), 50-300 AD. Museo Nacional de Arqueología, Antropología e Historia del Perú; Ministerio de Cultura del Perú © Yuvissa Mijulovich

Ironing Henkel Doppelausgussflasche in the form of a double-headed mythical snake. Clay, modeled and painted, burned, Early Nasca phase (style phase Nasca 3), 50-300 AD. Museo Didáctico Antonini; Ministerio de Cultura del Perú © Daniel Giannoni.

Gold jewelry plate in the form of a mythical double-headed serpent. Gold, hammered and driven. Early Nasca Period, 50-300 AD © Museo de Arte de Lima, Family Prado Estate.

Figurine border of a ceremony cape from Cahuachi. Museo Didáctico Antonini; Ministerio de Cultura del Perú © Nathalie Boucherie.

Ironing Henkel Doppelausgussflasche with a squid. Clay, modeled and painted, fired, Middle Nasca phase (style phase Nasca 4), 300-450 AD Private collection, Lima © Daniel Giannoni.

Twin antaras ( earthen panpipes) with human heads. Clay cast, painted, burned, early Nasca phase (Nasca 3 style phase), 50-300 AD, private collection, Lima © Daniel Giannoni.

Mug with the anthro-pomorphic Mythical creature with snake appendizes. Clay, modeled and painted, burned, late Nasca phase (style phase Nasca 6), 450-650 AD. Museo de Arte de Lima, Estate Family Prado © Daniel Giannoni.

Typical landscape of the Nasca area © Wolf-Dieter Niemeier

Geoglyph of a whale (Orca), Nasca 2017 © Alfonso Casabonne

Excavation in Tomb 4 of La Muña © Johny Isla

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_9bd94f_440340918-1658263111610368-58180761217.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_cfa6e3_440317478-1658265314943481-25907527200.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_844371_440162278-1658267648276581-39734064969.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_afd75f_telechargement-20.jpg)