Kunsthaus Zürich presents 'Fashion Drive. Extreme Clothing in the Visual Arts'

Jakob Lena Knebl, Chesterfield, 2014 (detail), Courtesy of Jakob Lena Knebl - Pleated skirt, c. 1526 (detail), Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Hofjagd- and Rüstkammer - William Larkin, Portrait of Diana Cecil, later Countess of Oxford, c. 1614-1618 (detail), English Heritage, The Iveagh Bequest (Kenwood, London) © Kunsthaus Zürich 2018

ZURICH.- From 20 April to 15 July 2018, visitors to the Kunsthaus Zürich can look forward to ‘Fashion Drive. Extreme Clothing in the Visual Arts’. More than 230 works – including everything from slashed clothing and codpieces to haute couture and street wear – testify the many ways artists have viewed, commented on and shaped the world of fashion through the centuries.

The exhibition spans art in multiple media from the Renaissance to the present day, with paintings, sculptures, installations, prints and watercolours, photographs, films, costumes and armour by some sixty artists.

Pleated robe, c. 1526. Probably owned by Albrecht, Margrave of Brandenburg, Duke of Prussia. Naked iron, partially etched: with black color fillings, leather, Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Hofjagd- and Rüstkammer © Kunsthaus Zürich 2018

ASTONISHING LOANS MAKING THEIR SWISS DEBUT

Curators Cathérine Hug and Christoph Becker have secured the loan of some truly eye-catching exhibits, including a set of Austrian folded skirt armour from around 1526 that has never before been seen in Switzerland. Works by the English School are also leaving their homeland for the first time; others, like the painting by Robert Peake depicting the ‘Gentlewoman of the Privy Chamber to Queen Elizabeth I’ (around 1600) in a lavishly embroidered silk dress, have only recently emerged from private collections.

Robert Peake and Workshop: Catherine Carey, Countess of Nottingham, circa 1597. Oil on canvas, 198.1 x 137.2 cm. Private collection, Courtesy of The White Gallery, London

A BALANCED, CRITICAL VIEW

The exhibition gives equal weight to male and female fashions, and includes a strong element of critique. Caricatures from the Lipperheidesche Kostümbibliothek costume library in Berlin take aim at the fashionistas and designers of the 19th century, while ‘high art’ comes under scrutiny too, as Jakob Lena Knebl (b. 1970) clothes sculptures by Maillol and Rodin that otherwise proudly display their nakedness. Artists and audiences know full well that there are two sides to fashion – or rather, the fashion business: inspiration, innovation and individual self-empowerment on the one, exclusion and profligacy on the other. The arrangement of works at the Kunsthaus reflects these subtle distinctions.

Jakob Lena Knebl: Chesterfield, 2014. Digital printing, variable format. Courtesy of Jakob Lena Knebl

RENAISSANCE AND BAROQUE

The presentation opens with magnificent paintings from the 16th century. In the Renaissance, slashed clothing and codpieces were all the rage; indeed the appeal of ripped garments, which has its origins in that era, is still with us to this day. The subsequent Baroque period saw the ruff vie with the décolleté: in contemporary portraits of introvert and extrovert personalities they represent enlightenment and the rejection of constraints imposed by religion and social status. Monarchs such as Elizabeth I and Louis XIV were among the first rulers to achieve global status, and they systematically employed their wardrobe to project and consolidate their power. They were imitated throughout Europe, including Switzerland.

Joos van Cleve: Suicide of the Lucretia, 1515-1518. Oil on oak, 47.7 x 35.3 cm, Kunsthaus Zürich, Ruzicka Foundation 1949 © Kunsthaus Zürich 2018

Hans Asper: Portrait of a man Wilhelm Frölich, Full-length portrait with coat of arms and coat of arms of the Frölich family, 1549. Oil and tempera on wood, 213 x 111 cm, Swiss National Museum, Zurich © Kunsthaus Zürich 2018

ROCOCO AND THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

The section on Rococo to the French Revolution shows how fashion and design blend into a hedonistic lifestyle from which others are excluded. The phenomenon of artists inspiring fashion is already in evidence here: the idiosyncratic pleat of the gown at the back of the shoulder is named after the painter Antoine Watteau! These innovations and extremes are strikingly illustrated in the paintings of Marie-Antoinette, the female ‘Merveilleuses’ (‘Marvellous Ones’) and their male counterparts, the ‘Incroyables’ (‘Unbelievables’).

Elisabeth Louise Vigée Lebrun: Marie-Antoinette en Chemise, 1783. Oil on canvas, 89.8 × 72 cm, Hessian House Foundation, Kronberg © Kunsthaus Zürich 2018

FIRST EMPIRE AND CONGRESS OF VIENNA

The First Empire and the Congress of Vienna that ended it see a reversion to older values. Service uniforms appear alongside military in the art of the time. Influential salon ladies such as Juliette Récamier have their portraits painted, inspiring their circle not only to invest in new furniture but also to adopt a neoclassical appearance. Napoleon may have fallen, but Paris still dictates what is fashionable. At the same time, the exhibition sheds new light on the significance of the Congress of Vienna (1814–15) to Europe’s new order. For the first time, powerful rulers turn up accompanied by their wives. Negotiations are conducted, but even more energy is devoted to festivities, which require a wardrobe to match and create plentiful work for local producers. The forms and techniques of the tailor’s art are present in everything from depictions of martyrs to the poses of victors.

Unknown artist: Départ des Amateurs de L'île St. Ouen, around 1805. Etching, hand-colored with watercolour, 21.2 x 26.2 cm, plate); 24.3 x 30.5 cm (sheet), Staatliche Museen zu Berlin - Kunstbibliothek © Kunsthaus Zürich 2018

PROGRESSION AND REGRESSION IN THE ERA OF INDUSTRIALIZATION

Visitors with a keen eye for nuances can try to spot the details in academic painting that distinguish the gentleman from the dandy. While such male types are considered modern, remarkably, ladies of the era revert to wearing the crinoline. Artists respond with a mixture of perplexity and amusement, readily visible in the paintings of Édouard Manet, Félix Vallotton, Contessa di Castiglione and, today, John Baldessari in which representation tips over into caricature.

Honoré Daumier: De l'utilité de la crinoline pour frauder l'octroi. From the benefit of the hoop skirt to cheat the customs. In: Le Charivari, 19.06.1857. Lithography, 26.7 x 20.8 cm, Kunsthaus Zürich © Kunsthaus Zürich 2018

Édouard Manet: Jeanne Duval, The Maîtresse de Baudelaire (La Dame à l'éventail), 1862. Oil on canvas, 113 x 90 cm, Museum of Fine Arts, Budapest © Kunsthaus Zürich 2018

John Baldessari: Double Bill: ... And Manet, 2012. Painted inkjet printing on canvas with acrylic and oil paint, 152.4 x 152.4 cm. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery, New York © John Baldessari

FASHION SETS STANDARDS

Consequently, the liberation of the body at the start of the 20th century does not come as a surprise. Fashion is opened up to a wider audience as it becomes affordable and is sold in department stores. Progressive artists such as Gustav Klimt and Emilie Flöge, Henry van de Velde and the Futurists Giacomo Balla and Filippo Marinetti all design clothes. Just as they tried to do with language, the Dadaists redefine the purpose of clothing. Man Ray and Erwin Blumenfeld narrow the gap between art photography and fashion photography, and Russian and French avant-gardists Natalia Goncharova and Sonia Delaunay respond with designs of their own. Ornament becomes fashionable and is woven or printed into both Art Nouveau imagery and clothing. Now the initially idealistic marriage of art and fashion has taken on a commercial dimension. Fashion designers and Pop Artists are linked by the cult of personality: both employ icons and use strident, bold symbols and slogans, as the works of James Rosenquist, Andy Warhol and Franz Gertsch testify. Youth cultures and subcultures become as inspirational for artists as they are for fashion designers. Fashion is now very much a material for artists.

Giovanni Boldini: Le Comte Robert de Montesquiou (1855-1921), 1897. Oil on canvas, 116 x 82.5 cm, Musée d'Orsay, Paris. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

Giacomo Balla: Bozetto by vestito da uomo, 1914. Watercolor on paper, 29 x 21 cm, Fondazione Biagiotti Cigna, © 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

BEYOND FASHION. A NEW REFLECTIVENESS

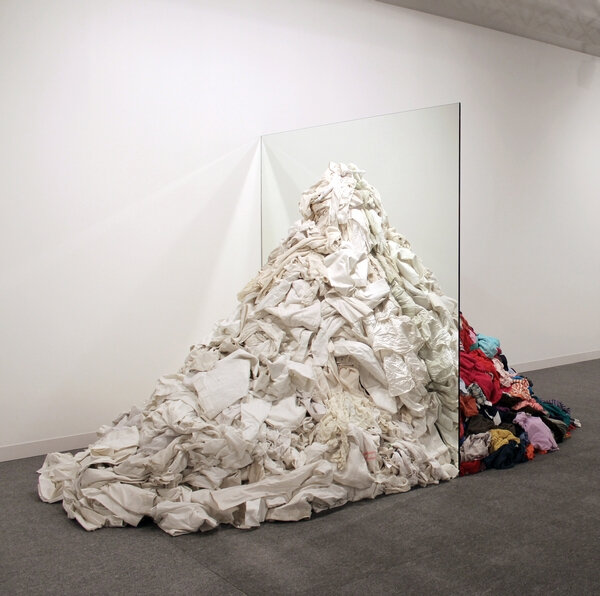

From haute couture via prêt-à-porter to fast fashion: the final section of the exhibition spans the arc to sustainability and post-human visions. Artificiality, the (de)construction of the body and a critique of the cult of brands are the hallmarks of 21st-century artistic production. Since Michelangelo Pistoletto, a young generation has been using installations, performances and videos to argue the case for ethically, ecologically and politically sustainable behaviour.

Michelangelo Pistoletto: Metamorfosi, 1976-2017. Mirrors, Rags. Installation view Abu Dhabi Art Fair, 2013, Galleria Continua, © Michelangelo Pistoletto

THE POINT OF IT ALL: FASHION AND WHAT IT MEANS

In this exhibition, the Kunsthaus Zürich sets out to synthesize and invite reflection on several centuries of art, fashion and social history and transform them into a sensual experience. Works from past eras are presented in surprisingly fresh ways, enabling visitors to rediscover their original meaning in a present-day context. Organized as part of the Festspiele Zürich, this attractive, humorous and instructive show is spread over 1000m2 and is accompanied by a publication and events. A catwalk full of potholes!

May-Thu Perret: Flow My Tears I, 2011. Mannequin with glass head, copy of Elsa Schiaparelli's skeleton dress after a design by Salvador Dalí, 1938, made by Naoyuki Yoneto, 175 x 70 x 70 cm. Courtesy of the artist and gallery Francesca Pia, Zurich © Mai-Thu Perret

Sylvie Fleury: Mondrian Dress Rack, 1993/2016 (detail), 3 Mondrian dresses, 1 coat rack, 3 hangers, mass variable. Courtesy Karma International, Zurich and Los Angeles © Sylvie Fleury

Sylvie Fleury: Untitled, 2016 (Valentino pattern green). Acrylic on canvas, 125 x 125 x 10 cm, Karma International Zurich, Los Angeles and Mehdi Chouakri Berlin © Sylvie Fleury

ARTISTS FROM 1500 TO THE PRESENT DAY

With works by around sixty artists – some familiar, some previously undiscovered – the exhibition is a logistical tour de force. It includes pieces by Hans Asper, Charles Atlas & Leigh Bowery, Hugo Ball, Giacomo Balla, John Baldessari, Joseph Beuys, Erwin Blumenfeld, Giovanni Boldini, Pierre Bonnard, Elisabeth Louise Vigée-Lebrun, Daniele Buetti, Paul Camenisch, Contessa di Castiglione & Pierre-Louis Pierson, Joos van Cleve, Isaac George Cruikshank, Salvador Dalí, Honoré Daumier, Albrecht Dürer, Nik Emch, Esther Eppstein, Max Ernst, Hans-Peter Feldmann, Sylvie Fleury, Emilie Flöge & Gustav Klimt, Heinrich Füssli, Johann Caspar Füssli, Franz Gertsch, James Gillray, Natalia Goncharova, Jacques Grasset de Saint-Sauveur, Johann Nikolaus Grooth, George Grosz, Richard Hamilton, David Herrliberger, Hannah Höch, Johann Nepomuk Höchle, Beat Huber, Jean Baptiste Isabey, Tobias Kaspar, Carl Joseph Keiser, Franz Krüger, William Larkin, Tamara de Lempicka, Les Frères Lumière & Loïe Fuller, Nicolas Lejeune, K8 Hardy, Jakob Lena Knebl, Herlinde Koelbl, Jirí Kovanda & Eva Kotátková, Inez van Lamsweerde & Vinoodh Matadin, Claude Lefèbvre, Robert Lefèvre, Peter Lindbergh, Nicolaes Maes, Édouard Manet, Manon, Malcom McLaren & Vivienne Westwood, Conrad Meyer, Dietrich Theodor Meyer the Elder, Anna Muthesius, Meret Oppenheim, Robert Peake, Mai-Thu Perret, Suzanne Perrottet & Johann Adam Meisenbach, Michelangelo Pistoletto, Charles Ray, Man Ray, Hyacinthe Rigaud, James Rosenquist, Tula Roy & Christoph Wirsing, Ashley Hans Scheirl, Michael E. Smith, Karl Stauffer-Bern, Elsa Schiaparelli, Wolfgang Tillmans, James Tissot, Félix Vallotton, Carle Vernet, Madeleine Vionnet, Édouard Vuillard, Andy Warhol, Jan Weenix, Mary Wigman, Charles Frederick Worth, Erwin Wurm, Andreas Züst. Loans come from public and private collections in Europe and from New York.

Max Ernst: Au dessus des nuages marche la minuit. Au dessus de la minuit plan l'oiseau invisible du jour. Un peu plus haut que l'oiseau l'éther pousse et les toits toits flottent, 1920. Photographic enlargement after the photomontage of the same name, 53 x 55 cm, Kunsthaus Zürich, © 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich

Tamara de Lempicka: Kizette en rose, 1927, oil on canvas, 116 x 73 x 1.3 cm, Nantes, art museum , agate à l'artiste, 1928. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais / Gérard Blot © Tamara Art Heritage / 2018 ProLitteris, Zurich.

Steve Schapiro: Portrait of James Rosenquist, Dressed in a Paper Suit, New York, 1966. Black and White Photography. Courtesy James Rosenquist Studio, Steve Schapiro, © Steve Schapiro

Peter Lindbergh: Linda Evangelista, Christy Turlington & Naomi Campbell, Brooklyn, 1990 Exhibition print, Hahnemuhle. Photo Rag® Baryta 315 gr, 60 x 50 cm. Courtesy of Peter Lindbergh, Paris, © Peter Lindbergh

Wolfgang Tillmans: Christos, 1992. From the Installation Im Kunstlicht, 1997. Color Photography, 60.8 x 50.7 cm, Kunsthaus Zürich © Wolfgang Tillmans

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F74%2F70%2F119589%2F111709125_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F12%2F07%2F119589%2F111686796_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F62%2F80%2F119589%2F111686682_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F07%2F73%2F119589%2F111686596_o.jpg)