Empresses of China's Forbidden City makes U.S. debut at Peabody Essex Museum

Ritual space in the Main Hall of the Palace of Longevity and Health. Courtesy of the Palace Museum, Beijing. © The Palace Museum

SALEM, MASS.- The Peabody Essex Museum debuts Empresses of China’s Forbidden City, the first major international exhibition to explore the role of empresses in China’s last dynasty––the Qing dynasty, from 1644 to 1912. Nearly 200 spectacular works, including imperial portraits, jewelry, garments, Buddhist sculptures, and decorative art objects from the Palace Museum, Beijing (known as the Forbidden City), tell the little-known stories of how these empresses engaged with and influenced court politics, art and religion. On an exclusive U.S. tour, this exhibition is a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to see rare treasures from the Forbidden City, including works that have never before been publicly displayed and many of which have never been on view in the United States. Coinciding with the 40th anniversary of the establishment of U.S.-China diplomatic relations, the exhibition is organized by the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts; the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery (Freer|Sackler), Washington, D.C.; and the Palace Museum, Beijing.

A leader in preserving and promoting Chinese art and architecture, PEM honors over 200 years of U.S.-Chinese commercial and cultural exchange through its renowned collection and exhibition program. Working closely with its partnering organizations, PEM presents this unprecedented exhibition in order to celebrate the vibrant legacy of cultural dialogue between these two countries.

With an international team of experts, exhibition co-curators Daisy Yiyou Wang, PEM’s Robert N. Shapiro Curator of Chinese and East Asian Art, and Jan Stuart, the Melvin R. Seiden Curator of Chinese Art at the Freer|Sackler, spent four years travelling to the Forbidden City to investigate the largely hidden world of the women inside. Delving into the vast imperial archives and collection, their fresh research unveils how these women influenced history as well as the spectacular art made for, by and about them. “This exhibition establishes a new model for future international research and museum collaborations,” says Dr. Shan Jixiang, director of the Palace Museum.

Seal of empress with double-headed dragon with box, tray, lock, key, and plaques. Imperial Workshop, Beijing, Republican period, 1922, gold alloy with silk tassels, Palace Museum, Gu167075. © The Palace Museum

REVEALING THE HIDDEN WORLD OF THE EMPRESSES

China’s grand imperial era––the Qing dynasty––was a multiethnic and multicultural state founded in 1644 by a small northeast Asian group who came to call themselves "Manchus." These conquering rulers adopted the Forbidden City in Beijing as the seat of the government. The Manchu ruling house differed from their populous Han Chinese subjects by language, history, and culture. In the Qing dynasty, Manchu customs prohibited foot-binding and encouraged women to learn to ride and hunt. In general, Manchu women enjoyed more freedom and rights than their Han Chinese counterparts.

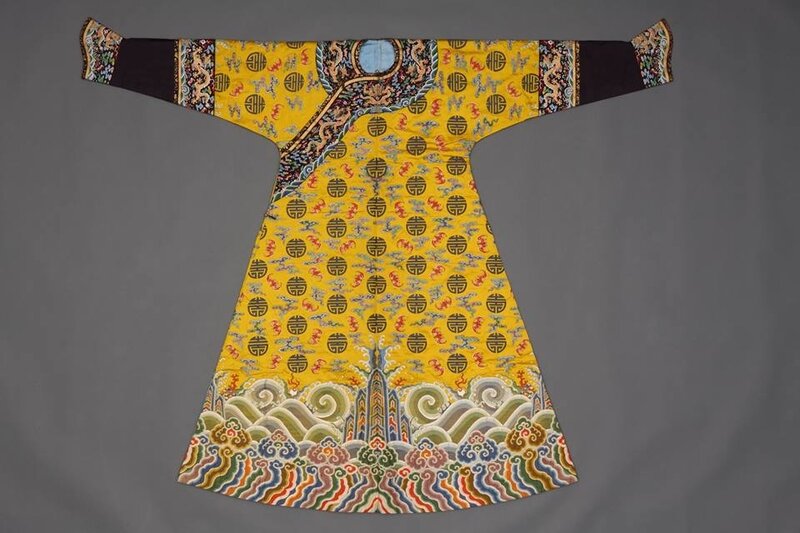

While the Qing imperial court was strictly patriarchal and hierarchical, a few empresses stood out and helped shape the long history of the dynasty. The empress headed the imperial harem and could influence the emperor. She was regarded as the “mother of the state” and a role model for all women. Presiding over the state ritual promoting silk production, empresses honored women’s vital role in the economic health of the state through textile production.

While the emperor-centric Qing imperial court recorded only skeletal outlines of the empresses’ lives, only recently have historians begun to fill in a more complete picture. Exhibition curators were able to reconstruct their rich and active lifestyles from the lavish art produced by the Qing court. Sumptuous objects showcased in this exhibition include the largest assemblage of imperial textiles and jewelry that have ever traveled to the U.S. from the Palace Museum. These works demonstrate how Qing dynasty empresses projected authority through what they wore, from stunningly embroidered socks to splendid dragon robes.

“We are very proud to reclaim the presence and influence of these empresses, about whom history has largely been silent,” says Daisy Wang, PEM’s curator for this exhibition. “The exquisite objects related to the empresses give us a better understanding of these intriguing women. Further evidence found in court archives and other historical sources help illuminate their hidden, but inspiring lives.”

STORIES OF OPULENCE AND INFLUENCE

Out of two dozen Qing empresses, this exhibition focuses on three key figures: Empress Dowager Chongqing (1693 - 1777), Empress Xiaoxian (1712 - 1748) and Empress Dowager Cixi (1835 - 1908). Their life experiences revolve around six core themes: imperial weddings, power and status, family roles, lifestyle, religion, and political influence.

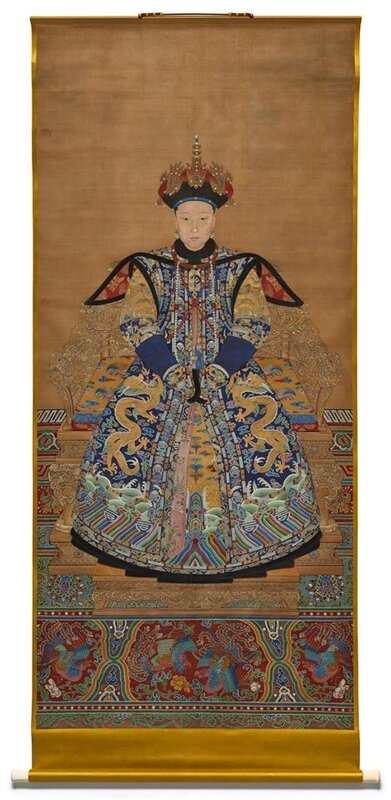

Empress Dowager Chongqing came from humble beginnings, entering a princely household as a maidservant at age 11 and bearing her only child at age 18. Her son eventually became the Qianlong emperor, which made Chongqing the focus of his filial piety, a core Confucian virtue. He honored her as the Sage Mother of the state, a status vividly captured by two life-size portraits of Chongqing in the exhibition. Following her death in 1777, she was commemorated by her son with a 237-pound gold shrine. Encrusted with gemstones, the shrine holds her hair to ensure her rebirth in the Buddhist paradise. As the largest of its kind in the Palace Museum’s collection, this shrine will be displayed at PEM and the Freer|Sackler for the first time outside of China.

Empress Dowager Chongqing at the Age of Seventy. Probably Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining; Italy, 1688–1766) and other court painters, Beijing, Qianlong period, about 1761, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, Palace Museum, Gu6452. © The Palace Museum.

Festive robe with bats, clouds, and the character for longevity. Probably Imperial Silk Manufactory, Nanjing (weaving), and Imperial Workshop, Beijing (tailoring), Qianlong period, 1785 or earlier, patterned silk satin and embroidery, polychrome silk and metallic-wrapped threads on silk fabric, Palace Museum, Gu42136. © The Palace Museum.

Pair of socks with phoenixes and other birds. Workshop, probably Jiangsu or Zhejiang province, Kangxi period, 1662–1722, embroidery, polychrome, metallic-wrapped, and peacock-filament-wrapped threads on silk satin with silk damask and silk lining, Palace Museum, Gu61795. © The Palace Museum.

Drinking Tea from Yinzhen’s Twelve Ladies. Court painters, Beijing, possibly including Zhang Zhen (active late 17th–early 18th century) or his son Zhang Weibang (about 1725–about 1775), Kangxi period, 1709–23, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, Palace Museum, Gu6458-7/12. © The Palace Museum.

Looking at Plum Blossoms from Yinzhen’s Twelve Ladies. Court painters, Beijing, possibly including Zhang Zhen (active late 17th–early 18th century) or his son Zhang Weibang (about 1725–about 1775), Kangxi period, 1709–23, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, Palace Museum, Gu6458-8/12. © The Palace Museum.

Stupa containing Empress Dowager Chongqing’s hair and Amitayus Buddha. Imperial Workshop, Beijing, Qianlong period, 1777, gold and silver alloy with coral, turquoise, lapis lazuli, and other semiprecious stones, and glass; pedestal: zitan wood, Palace Museum, Gu11866. © The Palace Museum.

Stupa containing Empress Dowager Chongqing’s hair and Amitayus Buddha (detail). Imperial Workshop, Beijing, Qianlong period, 1777, gold and silver alloy with coral, turquoise, lapis lazuli, and other semiprecious stones, and glass; pedestal: zitan wood, Palace Museum, Gu11866. © The Palace Museum.

One of a pair of “precious treasures” display cabinets (detail). Yongzheng or Qianlong period, 1723–95, lacquer with gold on wood core, metal with gilding, and ivory, Palace Museum, Gu207580. © The Palace Museum.

Fifteen-year-old Xiaoxian married the future Qianlong emperor while he was a prince. She became the empress after her husband ascended the throne. As childhood soulmates and confidants, Xiaoxian closely attended to her husband as he endured a months-long illness. She was a caring daughter-in-law and a wise manager of imperial family affairs, qualities that garnered her widespread respect.

In 1748, at the age of 36, Xiaoxian fell ill and died while traveling with her husband. In response, the heartbroken emperor brushed a poem to mourn his beloved wife. Empresses of China’s Forbidden City is the first exhibition to ever reveal this soulful elegy to the public.

Empress Xiaoxian. Ignatius Sichelbarth (Ai Qimeng; Bohemia, 1708–1780), Yi Lantai (active about 1748–86), and possibly Wang Ruxue (active 18th century), Qianlong period, 1777 with repainting possibly in 19th century, hanging scroll, ink and color on silk, Peabody Essex Museum, gift of Mrs. Elizabeth Sturgis Hinds,1956, E33619.

Court hat with phoenixes. Probably Imperial Workshop, Beijing, 18th or 19th century, sable, velvet, silk floss, pearls, tiger’s-eye stone, lapis lazuli, glass, birch bark and metal with gilding, and kingfisher feather, Palace Museum, Gu60084. © The Palace Museum.

Court hat with phoenixes (detail). Probably Imperial Workshop, Beijing, 18th or 19th century, sable, velvet, silk floss, pearls, tiger’s-eye stone, lapis lazuli, glass, birch bark and metal with gilding, and kingfisher feather, Palace Museum, Gu60084. © The Palace Museum.

Court hat with phoenixes (detail). Probably Imperial Workshop, Beijing, 18th or 19th century, sable, velvet, silk floss, pearls, tiger’s-eye stone, lapis lazuli, glass, birch bark and metal with gilding, and kingfisher feather, Palace Museum, Gu60084. © The Palace Museum

Festive robe with bats, lotuses, and the character for longevity. Probably Imperial Silk Manufactory, Suzhou (embroidery), and Imperial Workshop, Beijing (tailoring), Jiaqing period, 1796–1820, embroidery, polychrome and metallic-wrapped silk threads on silk tabby, Palace Museum, Gu43302. © The Palace Museum.

Hairpin with figure and vase. 18th or 19th century, pearls, sapphire, coral, turquoise, kingfisher feather, and silver with gilding, Palace Museum, Gu10130. © The Palace Museum.

Lobed fan with cranes, peaches, and rocks. Qianlong period, 1736–95, appliqué, silk fabric on silk gauze with pigments; handle: wood and ivory, Palace Museum, Gu136152. © The Palace Museum

Dressing case with mirror stand and handheld mirror. Qianlong period, mid- to late 18th century, with later repairs, lacquer with gold and polychrome decoration on wood core, zitan wood, suanzhi wood, mother-of-pearl, bone, metal with gilding; wood-framed mirror with embroidered silk case, Palace Museum, Gu180527. © The Palace Museum

Five-panel screen with phoenixes and birds in landscape (detail). Workshop, probably Guangzhou, Qianlong period, probably 1775 or earlier, panels: cloisonné, copper alloy with polychrome enamels and gilding; frame: zitan wood and nan wood, Palace Museum, Gu210730. © The Palace Museum

Ewer with lady and boy in garden on two sides. Imperial Workshop, probably Beijing, Qianlong period, probably 1760s or 1770s, cloisonné and painted enamel, copper and gold alloy with polychrome enamels and gilding, coral, turquoise, and lapis lazuli, Palace Museum, Gu11450. © The Palace Museum

Ewer with dragons and clouds. Probably Imperial Workshop, Beijing, Qianlong period, 1736–95, gold alloy, Palace Museum, Gu11455. © The Palace Museum

Amitayus Buddha in a niche (detail). Workshop, probably Tibet, Qianlong period, 1771, copper alloy with gilding and pigments; niche: zitan wood with silk damask, Palace Museum, Gu203040. © The Palace Museum.

Though tradition declared that “women shall not rule,” there was room for ambitious Qing empresses. Soon after giving birth to the Xianfeng emperor’s only heir, Cixi, a low-ranking consort, received a promotion. Facing a succession crisis after the death of her husband in 1861, Cixi, alongside the other empress dowager Ci’an (1837–1881), instigated a coup to gain political power and become co-regents to Cixi’s son, the child emperor. As the most powerful empress in Chinese history, Cixi ruled China for nearly half a century, bringing radical changes to the role of women in court politics and art patronage.

The exhibition culminates with a commanding sixteen-foot oil portrait of Empress Cixi. It was her gift to President Theodore Roosevelt in 1905. Cixi directed the American artist Katharine Carl to create an image of a youthful and benevolent ruler to express her good will to people in America at a time when U.S. and China experienced challenging relations. A recent conservation project at the Smithsonian has restored the painting to its original splendor. Empresses of China’s Forbidden City marks its first public display in the U.S. since the 1960s.

Empress Dowager Cixi. Katharine A. Carl (United States, 1865–1938), Guangxu period, 1903, painting: oil on canvas; frame: camphor wood, transfer from the Smithsonian American Art Museum, Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, S2011.16.1-2a-ap.

Empress Dowager Cixi. Photographed by Yu Xunling (1874–1943), Guangxu period, 1903–05, print from glassplate negative, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, FSA A.13 SC-GR-262, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, Purchase.

Empress Dowager Cixi with foreign envoys’ wives in the Hall of Happiness and Longevity (Leshou tang) in the Garden of Nurturing Harmony (Yihe yuan). Photographed by Yu Xunling (1874–1943), Guangxu period, 1903–05, print from glass-plate negative, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery Archives, FSA A.13 SC-GR-249. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC, purchase.

Festive headdress with phoenixes and peonies. Probably Imperial Workshop, Beijing, Tongzhi or Guangxu period, probably 1872 or 1888–89, silver with gilding, kingfisher feather, pearls, coral, jadeite, ruby, sapphire, tourmaline, turquoise, lapis lazuli, and glass; frame: metal, wires with silk satin, velvet, and cardboard, Palace Museum, Gu59708. © The Palace Museum

Festive headdress with phoenixes and peonies. Probably Imperial Workshop, Beijing, Tongzhi or Guangxu period, probably 1872 or 1888–89, silver with gilding, kingfisher feather, pearls, coral, jadeite, ruby, sapphire, tourmaline, turquoise, lapis lazuli, and glass; frame: metal, wires with silk satin, velvet, and cardboard, Palace Museum, Gu59708. © The Palace Museum

Festive robe with eight dragon-phoenix roundels and twelve imperial symbols. Imperial Silk Manufactory, Suzhou (embroidery), and Imperial Workshop, Beijing (tailoring), Guangxu period, about 1888–89, embroidery, polychrome and metallic-wrapped silk threads on silk tabby, Palace Museum, Gu44219. © The Palace Museum.

Hairpin with crab and reed. Daoguang period, 1834 or earlier, jade (nephrite), kingfisher feather, pearls, ruby, and silver with gilding, Palace Museum, Gu10223. © The Palace Museum

Pair of bracelets with bats, peaches, and flowers. Probably 19th or early 20th century, tortoiseshell with coral, kingfisher feather, pearls, ruby, jadeite, tourmaline, and silver with gilding, Palace Museum, Gu10371. © The Palace Museum.

Platform shoes with tiger heads, the character for longevity, and bats. Guangxu period, 1875–1908, appliqué, silk satin; platforms: wood core covered with cotton, glass beads, Palace Museum, Gu61568. © The Palace Museum.

“The study of women in history is exciting, timely and necessary,” says Jan Stuart, co-curator at the Freer|Sackler. “By focusing on the material and spiritual world of these women, we begin to fill in details absent from previous accounts of women in Chinese history. To the extent that the empresses’ experience of the expectations and constraints finds echo in our own world, we hope this exhibition will prompt broader reflection on the position of women in society and fosters a sense of commonality and connection across time and cultures.”

Surrounded by a dazzling array of imperial treasures, visitors will also discover engaging in-gallery interactive experiences, such as creating an empress’s robe. Other experiences include immersive videos and opera performance, as well as English and Chinese language label text and guided tours. In November 2018, halfway through the run of the six-month exhibition at PEM, an additional 30 artworks from the Palace Museum will be installed in the galleries, including magnificent paintings and imperial robes.

“This exciting exhibition fulfills our institutions’ shared commitment to expanding the appreciation of China’s rich culture, in this instance by recovering the preeminence of the Qing empresses through these stunning and rare objects,” notes Dan L. Monroe, the Rose-Marie and Eijk van Otterloo Director and CEO of Peabody Essex Museum, and Julian Raby, Director Emeritus, Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F17%2F45%2F119589%2F112519639_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F05%2F82%2F119589%2F112264930_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_dcd32f_telechargement-32.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_0d4ec9_telechargement-27.jpg)