Immersive exhibition explores five centuries of the artistic and cultural heritage of the city of Jodhpur and its people

Portrait of Maharaja Jaswant Singh II, 1895, Bert Harris, Jodhpur, oil on canvas, 59 7/8 × 48 3/8 in., Umaid Bhawan Palace, photo: Neil Greentree.

SEATTLE, WA.- The Seattle Art Museum presents Peacock in the Desert: The Royal Arts of Jodhpur, India (October 18, 2018–January 21, 2019), showcasing five centuries of artistic creation from the kingdom of MarwarJodhpur in the northwestern state of Rajasthan. Organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in partnership with the Mehrangarh Museum Trust of Jodhpur, the exhibition features 250 objects from the 16th to the mid-20th century including intricate paintings, decorative arts, elaborate tents, canopies, textiles, jewelry, and weapons, presented with photos and videos that evoke the impressive setting of the Mehrangarh Museum.

Peacock in the Desert presents a vision of a cosmopolitan court culture that relies on art as an essential aspect of its rule. Established in the 15th century, the city of Jodhpur was ruled by the Rathores for over seven centuries. The objects on view, many of which have not been seen beyond palace walls or traveled to the United States, tell the story of this vast desert kingdom.

The exhibition traces the kingdom’s cultural landscape as it was continuously reshaped by cross-cultural encounters, notably by two successive empires who ruled India: the Mughals and the British. These encounters introduced objects, artists, languages, architectural styles, and systems of administration that influenced the complex royal identity of the Rathore dynasty.

His Highness Maharaja GajSingh II of Marwar-Jodhpur established the Mehrangarh Museum Trust in 1972 and has overseen its evolution from a historic fort to a popular destination for visitors to Jodhpur from around the world. Both he and his daughter, Baijilal Shivranjani Rajye of Marwar-Jodhpur, will visit Seattle to see the exhibition in October.

SAM previously collaborated with the Mehrangarh Museum Trust on the popular exhibition Garden and Cosmos: The Royal Paintings of Jodhpur (January 29– April 26, 2009) at the Asian Art Museum.

“Peacock in the Desert opens an evocative window on the kingdom of MarwarJodhpur,” says Kimerly Rorschach, SAM’s Illsley Ball Nordstrom Director and CEO. “We’re grateful for the opportunity to present an experience of this multifaceted court culture to Seattle audiences.”

“The city of Jodhpur is not frozen in time, and royalty is not just about bling and splendor,” says Karni Singh Jasol, director of the Mehrangarh Museum Trust. “Ours is a museum of the 21st century, dedicated to promoting awareness of a vibrant and hard-working royal endeavor. With this exhibition, visitors have the opportunity to experience the colors, sights, and sounds of our unique culture, as well as our history of continual patronage throughout the centuries.”

EXHIBITION OVERVIEW

Peacock in the Desert is organized into six thematic sections. For the first time since the museum’s expanded building opened in 2007, the special exhibition begins in a spacious gallery on the third floor before continuing in the fourth floor special exhibition galleries.

Tradition and Continuity: The Royal Wedding Procession

Visitors are welcomed to the exhibition with a dramatic recreation of a royal wedding procession on the museum’s third floor. This immersive setting introduces visitors to the crucial role that marital alliances played in the lives of the citizens of Marwar-Jodhpur and in the development of the region’s aesthetic traditions. Life-size horse and elephant mannequins fill the space, adorned with an elephant howdah (seat), wedding regalia, and royal insignia. Video projections feature preparations for a 21st-century wedding and an aerial view of the Mehrangarh fort which encloses palaces, temples, and courtyards.

Royal Procession re-created at Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur, photo: Neil Greentree.

Cover for a Lady’s Palanquin, late 19th century or early 20th century, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

Installation view of Peacock in the Desert: The Royal Arts of Jodhpur, India at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, photo: Neil Greentree.

Howdah with Chattr (Elephant Seat with Parasol), early 19th century, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

The Mahi-o-maratib (Fish Insignia) in Procession, Jodhpur, ca. 1715, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

The Rathores of Marwar

A photographic montage introduces the desert landscape of Marwar-Jodhpur, its diverse peoples, and the exhibition’s central protagonists: the Rathore clan that ruled the region from the 13th to the mid-20th century. Two sculptural highlights include a gilt wood and glass mahadol (palanquin) that underlines the Rathores’ emphasis on dignified processions for kings and queens, and a large cradle for Krishna that demonstrates their spiritual leadership.

Mehrangarh Fort, Jodhpur, photo: Neil Greentree.

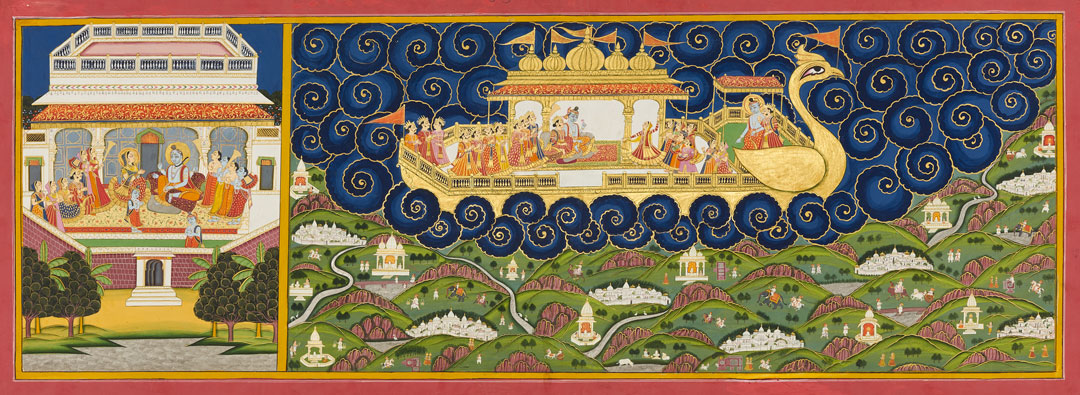

Shiva and Parvati in Conversation; Shiva on His Vimana (Aircraft) with Himalaya, Folio 53 from the Shiva Rahasya, 1827, Jodhpur, 1827, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

Palanquin (Mahadol), Gujarat, c. 1700–30, gilded wood, glass, copper & ferrous alloy, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

Krishna Jhula (Cradle for Krishna), late 19th century, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

Portrait of Maharaja Ajit Singh, ca. 1830, , Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

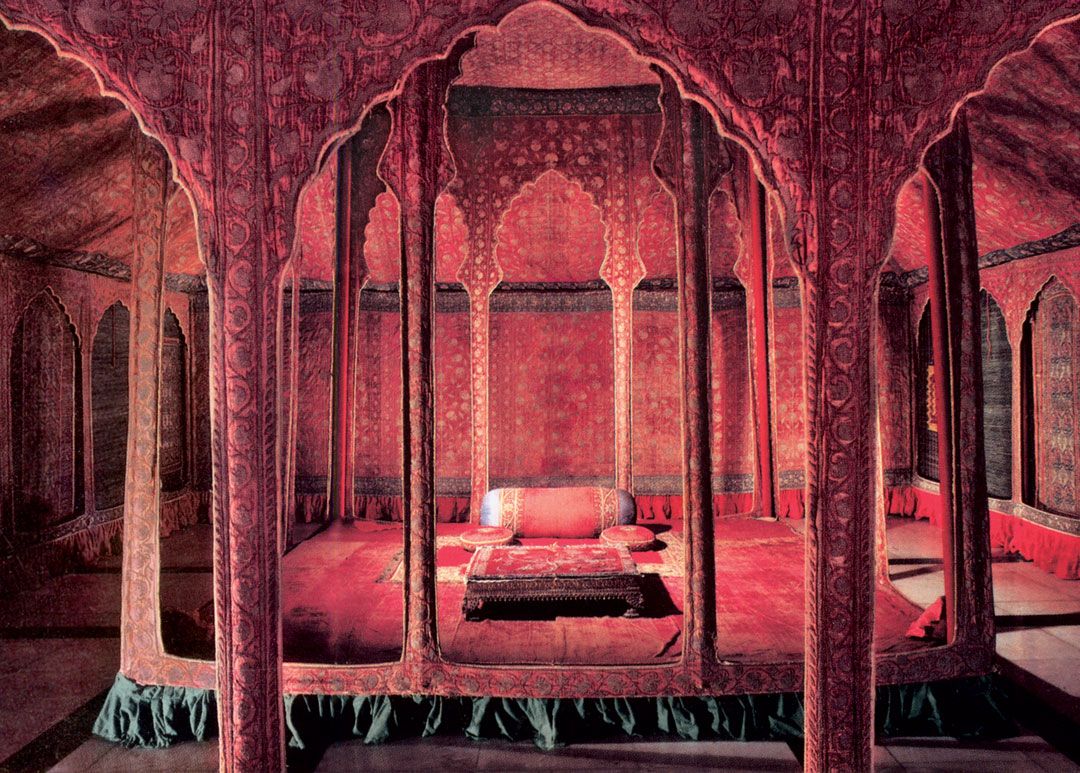

Conquest and Alliance: The Rathores and the Mughals

The arrival of, and eventual takeover by, the Mughal Empire in 1561 began centuries of political and military alliances between the Mughals and the Rathores. This section examines the movement of objects throughout these alliances in the 16th and 17th centuries, presenting ornate sabers, daggers, and rifles alongside 17th- and 18th-century paintings and illustrations of the court and portraits of kings. The section begins with the extraordinary 17thcentury Lal Dera tent, one of the oldest, if not the only, intact Indian court tents in existence.

The Lal Dera, late 17th to early 18th century, photo: Neil Greentree.

Khanjar (Dagger), late 17th or early 18th century, photo: Neil Greentree.

Mughal, Huqqa Vase, early 18th century, glass and gold paint, Umaid Bhawan Palace, photo: Neil Greentree.

Dalchand, Maharaja Abhai Singh on Horseback, ca. 1725, Jodhpur, c. 1725, opaque watercolor and gold on paper, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

Zenana: Cross-Cultural Encounters

In this section, paintings, carpets, textiles, and jewelry evoke the setting of a royal zenana, the women’s wing of a Rathore palace. Here, the zenana is explored as a hub of language, exchange, and culture led by the women of the court. They played a crucial role as agents of cultural change and patrons of the arts, preserving cultural traditions of festivals and dress throughout the centuries. Among the furnishings shown in this section is an exceptional wood baradari (pavilion). A sequence of paintings emphasize the unique role of women as patrons of festivals that marked the seasons.

Nagaur, Women of the Zenana Watch a Dance Performance with Bakhat Singh, ca. 1736, aque watercolor and gold painting, photo: Neil Greentree.

Baradari (Pavilion), Jodhpur, 19th century, wood, paint, lacquer, and gold, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

A Durbar in the Zenana, ca. 1850, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

Choker Necklace, 18th or 19th century, gold, diamonds, pearls, emeralds and enamel, © The al-Sabah Collection, Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyyah, Kuwait.

Jhula (Swing), late 19th century, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

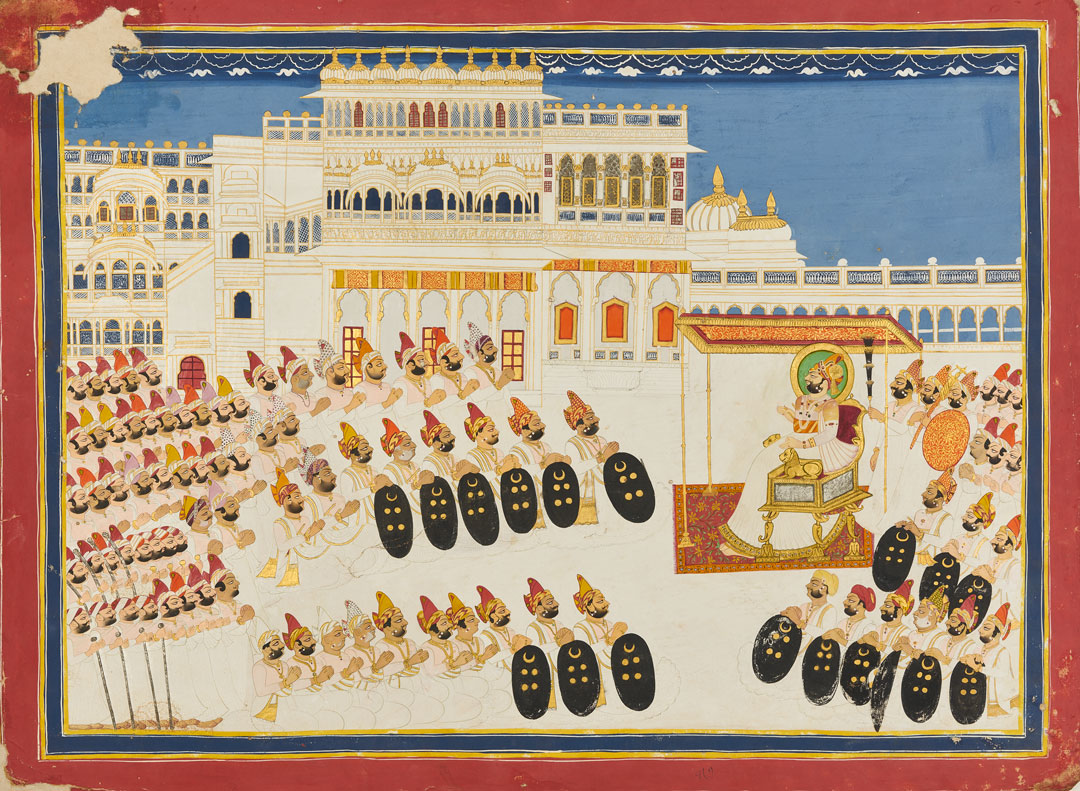

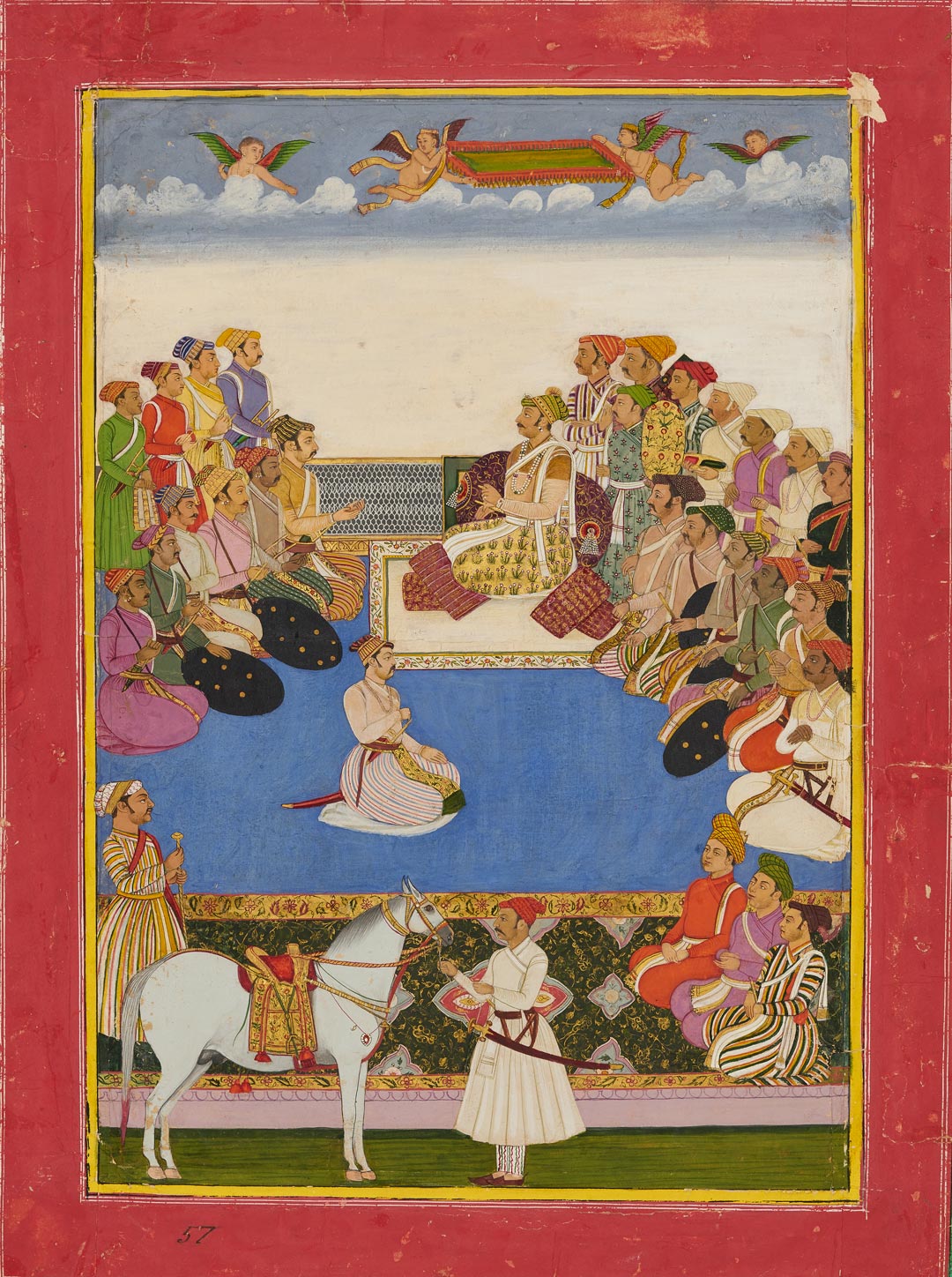

Durbar: The Rathore Court

As Mughal influence began to decline in the late 18th century, artists, craftspeople, and nearby dynastic kingdoms were attracted to Jodhpur due to its increased stature. This shift is seen in paintings of durbars (royal receptions) staged by the Rathores. Alongside these developments came the growing trend of exchanging artworks as gifts. This led to a period of intense creativity in artistic production and a cross-fertilization of Mughal and Rathore styles, seen in the woven canopy and textiles, finely crafted arms and armor, and 18th- and 19th-century paintings on view.

The Court of Maharaja Man Singh, ca. 1830, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

Singhasan with Chattr (Throne with Parasol), mid-19th century,

Maharaja Gaj Singh I Holding Court, ca. 1800, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

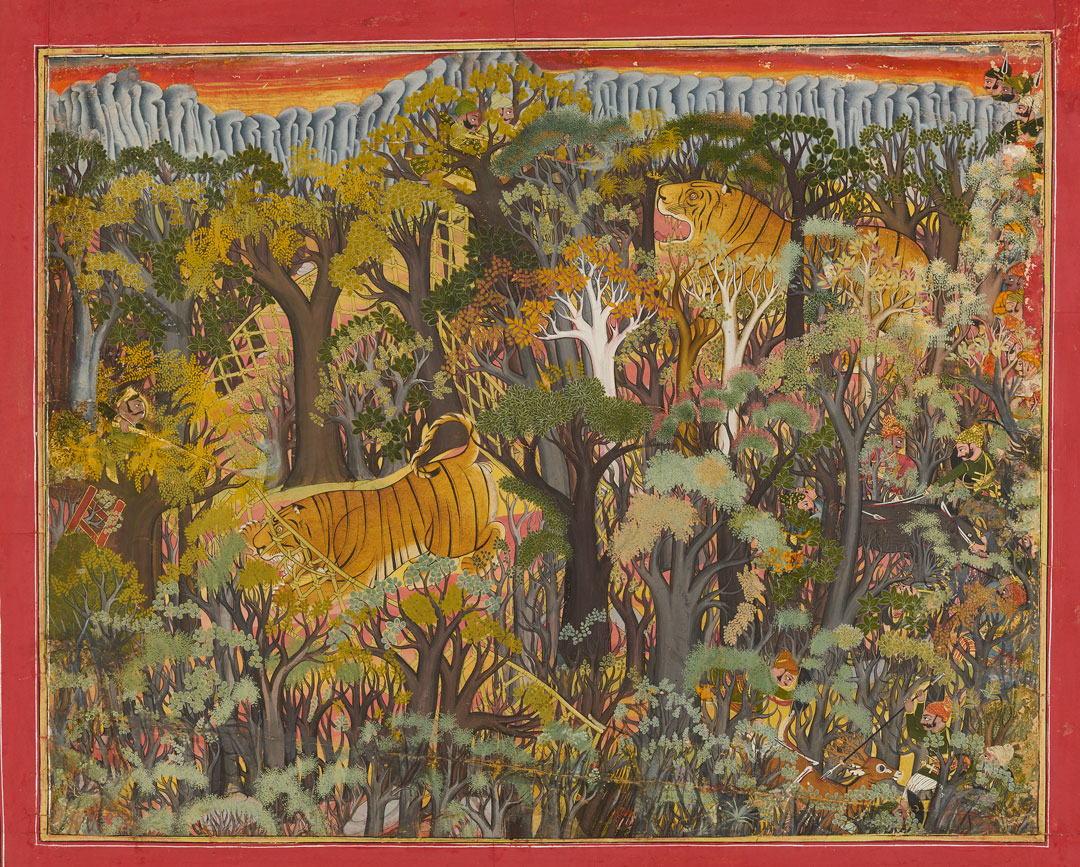

Sheikh Taju, Maharao Umed Singh of Kota on a Hunt, 1780. Opaque Watercolor And Gold On Paper, 52 x 66 cm, Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

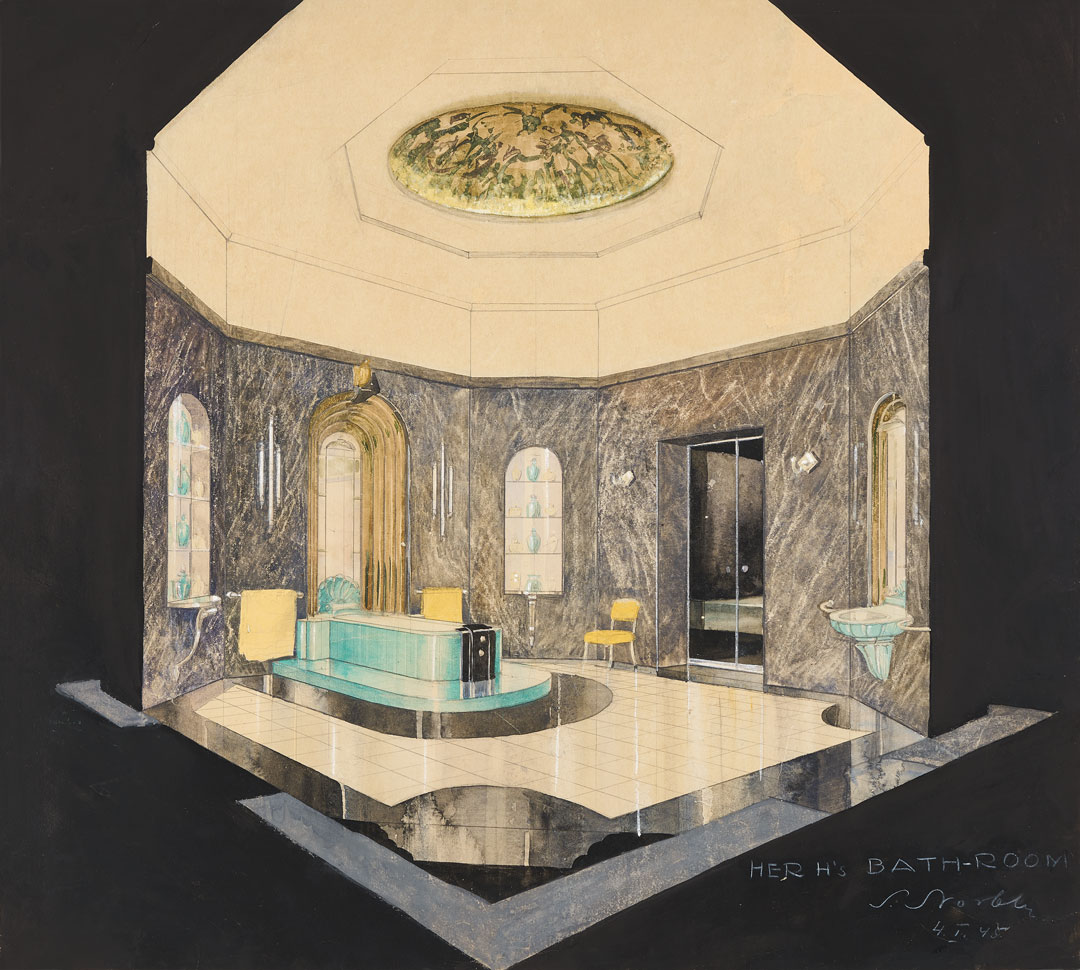

The Raj

A dramatic transformation in Jodhpur is triggered by India’s encounters with the British Empire in the 19th century. By 1876, Queen Victoria took the title of Empress of India and set off a new wave of European aesthetics. Merging with traditional Indian garments, paintings, and jewelry, an imperial hierarchy was emphasized during the era known as the Raj. During the 20th century, the Maharajas of Jodhpur became renowned for innovative patronage. In 1944, Umaid Bhawan Palace was completed and is now operated as a hotel by the Taj Group. Today, this legacy continues with the current leader of Marwar-Jodhpur.

Umaid Bhawan Palace at sunset. photo: Neil Greentree.

Bert Harris, Portrait of Maharaja Sardar Singh, 1896. Oil On Canvas, 250 x 162 cm, Umaid Bhawan Palace, photo: Neil Greentree.

Sculpture of a Peacock, early 20th century. Mehrangarh Museum Trust, photo: Neil Greentree.

Bert Harris, Portrait of Maharaja Jaswant Singh II, 1895, Jodhpur, oil on canvas, 59 7/8 × 48 3/8 in., Umaid Bhawan Palace, photo: Neil Greentree

Design for Her Highness’s Bathroom at Umaid Bhawan Palace, 1944, photo: Neil Greentree

Sarpech (Turban Ornament), Probably second half of 17th century, © The al-Sabah Collection, Dar al-Athar al-Islamiyyah, Kuwait.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_dcd32f_telechargement-32.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_0d4ec9_telechargement-27.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_fa9acd_telechargement-23.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_9bd94f_440340918-1658263111610368-58180761217.jpg)