Christie's announces highlights from the Fine Chinese Ceramics & Works of Art auction

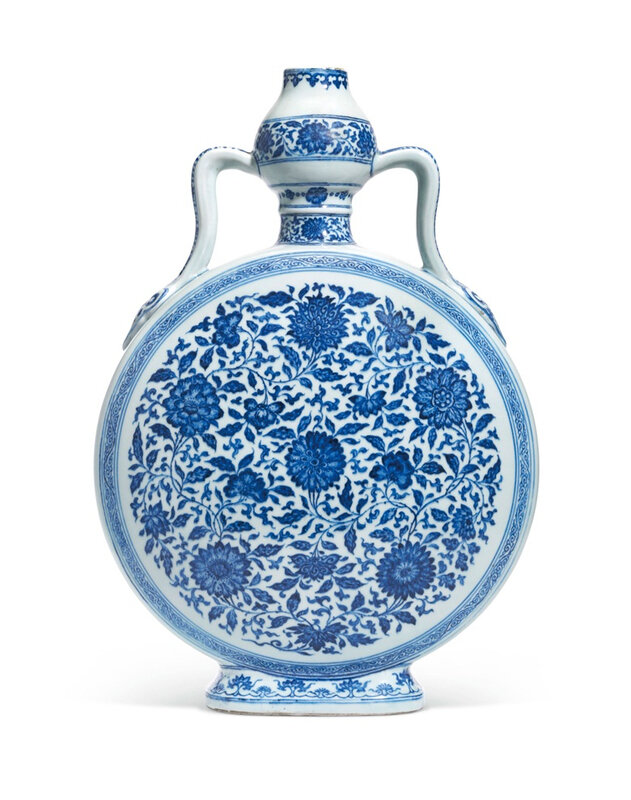

Lot 171. A Rare Large Ming-Style Blue and White Moonflask, Bianhu, Yongzheng six-character seal mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1725-1735); 20 7/8 in. (53 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 1,200,000 - GBP 1,500,000 (USD 1,568,400 - USD 1,960,500). Price realised GBP 1,448,750. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018

LONDON.- On 6 November 2018, Christie’s Fine Chinese Ceramics & Works of Art auction will present an array of rare works of exceptional quality and with important provenance, many offered to the market for the first time in decades. The season will be highlighted by exquisite imperial ceramics, fine jade carvings, Buddhist art, huanghuali furniture, paintings from celebrated modern Chinese artists, along with works of art from a number of important collections, including The Soame Jenyns Collection of Japanese and Chinese Art. The works will be on view and open to the public from 2 to 5 November.

The auction will be led by a moonflask, Bianhu, Yongzheng six-character seal mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1725-1735) (estimate on request). This magnificent flask is exceptionally large, and takes both its form and decoration from vessels made in the early 15th century. The Yongzheng Emperor was a keen antiquarian and a significant number of objects produced for his court were made in the antique style, particularly blue and white porcelain, and so their style was often adopted for imperial Yongzheng wares in the 18th century. The vessel is decorated with stylised floral scrolls and a pair of elegant strap handles, each decorated with flowers and foliage, terminating in ruyi heads.

Lot 171. A Rare Large Ming-Style Blue and White Moonflask, Bianhu, Yongzheng six-character seal mark in underglaze blue and of the period (1725-1735); 20 7/8 in. (53 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 1,200,000 - GBP 1,500,000 (USD 1,568,400 - USD 1,960,500). Price realised GBP 1,448,750. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018

The vessel is decorated to each convex side of the flattened circular body with a network of stylised floral scrolls, cleverly highlighted with simulated heaping and piling effect, all within a narrow scroll border. The shoulders are applied with a pair of elegant strap handles, each decorated with meandering foliage bearing flowers, terminating in ruyiheads, all below the 'garlic' neck painted with several horizontal bands of floral scrolls.

Provenance: Acquired in Asia by the grandfather of the current owner between 1920-1943.

This magnificent flask is exceptionally large, and takes both its form and its decoration from vessels made in the early 15th century. The Yongzheng Emperor was, like his father, a keen antiquarian and a significant number of the art items made for his court were made in antique style. The blue and white porcelains of the early 15th century were particularly admired, and so their style was often adopted for imperial Yongzheng wares. Indeed, the famous director of the imperial kilns, Tang Ying (唐英1682-1756), who first came to Jingdezhen as resident assistant in 1728 and stayed until well into the Qianlong reign, was especially celebrated for his success in imitating earlier wares. The 1795 Jingdezhen tao lu 景德鎮陶錄by 藍浦Lan Pu noted that: ‘his close copies of famous wares of the past were without exception worthy partners [of the originals]’.

For most connoisseurs of Chinese ceramics, the so-called moon-flasks are classic Chinese porcelain forms. However, the form has a surprisingly long history in international art, although it is possible that the Chinese early Ming dynasty form was inspired either by metalwork or glass of the Islamic era, as argued by B. Gray in ‘The Influence of Near Eastern Metalwork on Chinese Ceramics’, Transactions of the Oriental Ceramic Society, vol. 18, 1940-41, p. 57 and pl. 7F). However, one of the earliest flattened circular flasks with handles joining the mouth of the vessel to the shoulder on either side of the neck is the unglazed pottery flask decorated with an octopus painted in dark brown, which was found among the late Minoan artefacts at Palaikastro on the island of Crete. The Minoan flask dates to about 1500 BC, and thus was contemporary with the Shang dynasty in China (illustrated by Spyridon Marinatos and Max Hirmer, Crete and Mycenae, New York, 1960, pl. 87).

One version of the Chinese ceramic moon-flask shape, which has no upper bulb, but simply a circular body with rounded edges looks as though should have its origins in two bowls being stuck together rim to rim, although in fact the early Chinese form is luted horizontally, not vertically. The Minoan flask, however, appears to have been made in precisely the former method. Examples of slightly later vessels are the flattened circular flasks from Nineveh - in this case with their handles on the shoulders - dating to the Parthian period (150 BC-AD 250), which is roughly contemporary with the Han dynasty in China (a number are preserved in the collection of the British Museum). A number of glazed pottery flasks of flattened circular form with handles on either side of the neck are found among Sassanian ceramics (AD 224-642). A small Sassanian flask with turquoise glaze, from Šuš, in the Iran Bastan Museum, is close to the Parthian example, and reasonably close to one of the early fifteen century Chinese porcelain moon-flask shapes - the strap handles joining the lower part neck, if not the mouth (The World’s Great Collections - Oriental Ceramics, Vol. 4, Iran Bastan Museum Tehran, Tokyo, 1981, colour plate 12). A green glazed earthenware pilgrim flask, also from Šuš, dates to the Sassanian period (AD 224-642), and is also in the collection of the Iran Bastan Museum, Teheran (illustrated ibid., black and white plate 101). This flask has flat encircling sides forming a relatively sharp junction with the front and back circular panels, which are noticeably domed, similar to later metalwork examples, and also similar to the lower section of 15th and 18th century flasks, such as the current vessel.

Interestingly a similarly shaped flask - circular with sharp angles to flat sides - was made in China during the Liao dynasty (916-1125), and a green-glazed example - without handles, but with six loops spaced around the flat sides for suspending the vessel from a saddle - was excavated from a tomb in Inner Mongolia in 1965 (See Zhongguo wenwu jinghua daquan - Taoci juan 中國文物精華大全陶瓷卷, Taipei, 1994, p. 164, no. 560). Unlike most early circular flasks this vessel stands on a rectangular foot similar to that on the later porcelain flasks, including the current Yongzheng moon-flask. A number of similarities can be seen between the Liao 10th-11th century vessel and both the flattened moon-flasks with upper bulb made in China in the Yongle and Xuande reigns, which inspired the current vessel - such as the example from the Riesco Collection sold by Christie’s Hong Kong on 27 November 2013, lot 3111 - and the large, flat-backed Chinese porcelain flasks without a bulb upper section, which were made in the early 15th century, with loop handles on the sides of the vessel, one of which was sold by Christie’s London on 6 November 2007, lot 156.

A distinct foot can also be seen on a green glass flask in the Tareq Rajab Museum in Kuwait (illustrated on http://www.trmkt.com/glassdetails.htm). This is a Syrian flask from the late 7th or early 8th century - contemporary with the Tang dynasty in China, and was made of mould blown and cut glass. A vessel of identical form was found in an excavation at Tarsus in south-eastern Anatolia in the 1930s, in a context with Umayyad and early Abbasid pottery. The handles attach only to the lower part of the neck of this vessel. Although these glass forms could have made their way to China, as Near Eastern glass was much appreciated in the Tang dynasty, metalwork seems a more likely inspiration for the specific form of the precursors of the current flask. There is a somewhat larger Syrian brass canteen, dating to the mid-13th century, in the collection of the Freer Gallery, Washington (illustrated on http://www.asia.si.edu/exhibitions/online/islamic/artofobject1b.htm), which is of very similar form to the lower section of the two-section flasks, and has close similarities with the single section, flat-backed flask sold by Christie’s in November 2007, mentioned above. Interestingly the brass canteen is decorated with Christian imagery as well as calligraphy, geometric designs and animal scrolls. This Syrian mid-13th century brass canteen in the Freer Gallery appears to be the only published example of such a metal vessel, but it shares a number of features with the form of the Chinese porcelain two-section flasks, having both a bulb-shaped mouth and similarly S-form handles.

When the flattened flasks with upper and lower section in double-gourd form appear in porcelain at the Chinese Imperial kilns at Jingdezhen in the early 15th century, they appear with varied proportions, and in both plain white and blue and white. A plain white example of the larger type from the Yongle reign (1403-24), which was excavated from the early Yongle stratum at the Imperial kilns, is illustrated in Imperial Porcelain of the Yongle and Xuande Periods Excavated from the Site of the Ming Imperial Factory at Jingdezhen, Hong Kong, 1989, pp. 92-3, no. 5. A blue and white Yongle flask of the smaller size is in the collection of the British Museum (illustrated by J. Harrison Hall, Ming Ceramics in the British Museum, London, 2001, p. 110, no. 3:21). Large and smaller flasks decorated and undecorated were made in the Yongle and Xuande periods, and the Yongle vessels usually stand on an oval foot, while the Xuande examples usually have a rectangular foot. The Yongle vessels do not have reign marks, while some of the Xuande flasks have the reign mark written in underglaze blue in a horizontal line below the mouth.

It has been suggested by some authors that these flasks, particularly the blue and white examples with decoration clearly inspired by Islamic arabesques, were made solely for export to the Islamic West. However, one crucial piece of evidence suggests that this is not the case. A shard from one of these flasks, bearing the same decoration as the vessel sold by Christie’s Hong Kong in 2013 was excavated from the Yongle/Xuande stratum at the site of the early Ming dynasty Imperial Palace in Nanjing (See A Legacy of the Ming, Hong Kong, 1996, p. 48, no. 52). Clearly these elegant flasks were also appreciated by the Chinese court in the first half of the 15th century. This imperial appreciation is also demonstrated in the 18th century by the vessels, such as the current Yongzheng flask, which were so closely inspired by the early 15th century examples.

A much smaller Yongzheng flask of similar shape with decoration, which precisely imitates Xuande 15th century flasks, is in the collection of the Shanghai Museum (see 陸明華Lu Minghua ed., Qingdai qinghua ciqi jian shang 清代青花瓷器鑒賞, Shanghai, 1996, pl. 16). A further smaller Yongzheng moon-flask, with bulb mouth and twin handles, and decorated in 15th century style, is illustrated by 錢振宗 Qian Zhenzong in Qingdai ciqi shangjian 青代瓷器賞鑑, Hong Kong, 1994, p. 84, no. 97. The mixed floral scroll seen on the current flask is also was also inspired by early 15th century imperial porcelains, but was more frequently applied to meiping vases, large bulbous flasks or open wares. However, the 18th century decorator clearly saw the potential for its application to enhance the current flask. Significantly, a Yongzheng blue and white moon-flask with short straight neck and twin handles, without a raised foot, in the collection of the Palace Museum Beijing, is decorated with a similar mixed floral scroll to that on the current flask (see 故宮博物院藏 青代御窰瓷器 Gugong Bowuyuan cang – Qingdai yuyao ciqi, volume I-2, Beijing, 2005, pp. 104-5, no. 41). The Beijing flask also bears a reign mark of similar style to that on the current flask.

The sale will be highlighted by important works of art from the collection of the late Soame Jenyns which will be presented across the Fine Chinese Ceramics and Works of Art sale, alongside an online sale which runs from 1 to 8 November. Soame Jenyns (1904-1976) was a legendary figure in the field of Chinese and Japanese art. He was an esteemed British art historian, collector and connoisseur and worked at the British Museum authoring several seminal books on East Asian art. The collection was built throughout his lifetime and will be led by a gilt-bronze figure of Avalokiteshvara (1426-1435) (estimate £150,000-200,000). It is engraved with a six-character inscription, which can be translated as ‘Bestowed [during the] Xuande era [of the] great Ming’. The figure perfectly reflects the connoisseurship of Soame Jenyns. Radiological examinations of the figure have revealed small consecratory objects: a miniature scroll, various textile fragments and beads. It is rare for the base plate of such an old bronze to be intact and confirms that the figure had been consecrated in a Buddhist ritual. Both aspects are highly appreciated by collectors of Buddhist bronzes.

Lot 26. A Rare and Finely-Cast Gilt-Bronze Seated Figure of Avalokiteshvara, Xuande six-character incised mark and of the period (1426-1435); 10 ¼ in. (26 cm.) high. Estimate: £150,000-200,000 (USD 196,050 - USD 261,400). Price realised GBP 1,928,750. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018.

The bodhisattva is shown seated in lalitasana with the right foot supported on a lotus stem that projects from the front of the double-lotus base. The hands are held invitarkamudra with the left hand held in front of the chest and the right hand resting on the knee, each holding the ends of a lotus stem, extending up the arms to flank the shoulders. The graceful figure wears an elegantly draped dhoti secured with a beaded, festoon-hung sash, beaded necklaces, armlets, large circular earrings and an elaborate tiara with eight foliate points that surrounds a seated figure of Amitabha Buddha and the artfully arranged chignon. The reign mark, Da Ming Xuande nian shi, which can be translated as 'Bestowed in the Xuande reign of the Great Ming dynasty', is inscribed in a line at the front of the base. The figure is richly gilded, and the base is sealed with a plate inscribed with a double vajra.

Radiograph showing the interior of the figure.

Provenance: Collection of the late Soame Jenyns (1904-1976), then by descent within the family.

Seated Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara

Robert D. Mowry 毛瑞

Alan J. Dworsky Curator of Chinese Art Emeritus,

Harvard Art Museums, and

Senior Consultant, Christie’s

This exquisite sculpture represents the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion, as indicated by the presence in the headdress of a small seated image of the Buddha Amitabha 阿彌陀佛. Avalokiteshvara is known formally in Chinese as Guanshiyin Pusa 觀世音普薩, but the name typically is contracted simply to Guanyin 觀音. Considered a spiritual emanation of Amitabha, Avalokiteshvara is the only bodhisattva in whose crown or headdress Amitabha appears, and thus Amitabha’s presence here definitively identifies this figure as Avalokiteshvara, who is sometimes also called Padmapani 波頭摩巴尼 (“Holder of the Lotus”) or Lokesvara 世自在 or 世自在王 (“Lord of the World”).

Elegantly outfitted in the sumptuous trappings of an Indian prince of old, bodhisattvas 菩薩 are benevolent beings who have attained enlightenment 菩提 but who have selflessly postponed entry into nirvana 涅槃 in order to assist other sentient beings—有情 or 眾生—in gaining enlightenment. Meaning “enlightened being”, a bodhisattva is an altruistic being who is dedicated to assisting other sentient beings in achieving release from the samsara cycle of birth and rebirth 輪迴 through the attainment of enlightenment; bodhisattvas thus embody the Mahayana Buddhist 大乘佛教 ideal of delivering all living creatures from suffering 普渡眾生.

Bodhisattvas are presented in the guise of an early Indian prince, a reference to Siddhartha Gautama’s worldly status as a crown prince before he became the Historical Buddha Shakyamuni 釋迦牟尼佛, implying that just as Siddhartha 喬達摩悉達多 (traditionally, c. 563–c. 483 BC) became a Buddha 佛, so will bodhisattvas eventually become Buddhas, once all sentient beings have attained enlightenment.

As evinced by this compelling sculpture, bodhisattvas generally are depicted with a single head, two arms, and two legs, though they in fact may be shown with multiple heads and limbs, depending upon the individual bodhisattva and the particular manifestation as described in the sutras 佛經, or sacred texts. Richly attired, bodhisattvas, who may be presented either standing or seated, are represented with long hair often arranged in a tall coiffure, or bun, atop the head and often with long strands of hair cascading over the shoulders; as evinced by this sculpture, a crown sometimes surrounds the topknot. Bodhisattvas wear ornamental scarves, dhotis of rich silk brocade, and a wealth of jewelry that typically includes necklaces, armlets, bracelets, and anklets. Like Buddhas, bodhisattvas have distended earlobes; some, like this Avalokiteshvara wear earrings, others do not. Though bodhisattvas generally are shown barefoot, as in this example, both early Indian and early Chinese images of bodhisattvas may be shown wearing sandals, often of plaited straw.

In addition to the image of the Buddha Amitabha atop the head, which is Avalokiteshvara’s definitive identifying attribute, the bodhisattva typically holds such iconographic attributes as a lotus blossom, a vase, a ritual kundika vessel 淨瓶 for holy water, or is portrayed in association with a willow branch, a Buddhist symbol of healing, both physical and spiritual. In addition to those that comprise the base, two lotus blossoms flank this bodhisattva, one at each shoulder.

A translation of the Sanskrit name Avalokiteshvara, Guanshiyin means “[The One Who] Perceives the Sounds of the World”, a reference to Guanyin’s ability to hear both the cries of the afflicted and the prayers of supplicants. An earthly manifestation of the Buddha Amitabha, Guanyin guards the world in the interval between the departure of the Historical Buddha Shakyamuni and the appearance of Maitreya 彌勒, the Buddha of the Future. The Lotus Sutra—known in Sanskrit as the Saddharma Pundarika Sutra and in Chinese as the Miaofa Lianhua Jing 妙法蓮華經—is generally accepted as the earliest sacred text that presents the doctrines of Avalokiteshvara, that presentation occurring in Chapter 25. Titled Guanshiyin Pusa Pumenpin 觀世音菩薩普門品 and devoted to Guanyin, that chapter describes Guanyin as a compassionate bodhisattva who hears the cries of sentient beings and who works tirelessly to help all those who call upon his name. Thirty-three different manifestations of the bodhisattva are described, including female manifestations as well as ones with multiple heads and multiple limbs.

The style of this sculpture belongs to a long artistic tradition that can be traced to northeastern India in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, which then spread to Nepal and Tibet. The flowering of the Nepali variant of the style in China during the Yuan dynasty 元朝 (1279-1368) is often linked to the influence of Anige 阿尼哥 (1245-1306), a young Nepali artist who was brought to Beijing in 1262 by Chogyal Phags’pa (1235-1280), an influential Tibetan monk of the Sakya sect and state preceptor for Khubilai Khan (1215-1294), the founder of the Yuan dynasty. Anige played an important role at the Mongol court, serving as the director of all artisan classes and the controller of the Imperial Manufactories Commission.

Although Tibetan Buddhist imagery began to appear in the repertory of Chinese art already in the Yuan dynasty, Tibetan influence on Chinese Buddhist art became far more pronounced in the Ming dynasty 明朝 (1368-1644), particularly during the Yongle era 永樂 (1403-1425), when the imperial court looked favorably upon Buddhism and made a concerted effort to build secular and religious alliances with Tibet, even inviting Tibetan monks to the capital, Beijing, to conduct religious services. Such Tibetan influence manifests itself in the sensuousness of the art, as witnessed in this figure’s elegant proportions, S-curved posture, dazzling jewels, refined gestures, abundant and meticulously rendered details, and compressed double-lotus base. As important as Tibetan-influenced works of art were early in fifteenth-century China, particularly in the Yongle and Xuande 宣德 (1426-1435) reigns, Tibetan-style Buddhism probably was little practiced outside the imperial court, so most such images likely were made for the court, as indicated by the imperial inscriptions.

The bodhisattva’s broad shoulders, smooth torso, and long legs derive from Indian traditions, as do the thin clothing and such items of jewelry as the armbands. By contrast, the large circular earrings; the broad, somewhat square face with high cheekbones and elegant, curved eyebrows; and the prolific use of inlays stem from Nepali and Tibetan traditions.

Numerous sculptures in this Nepali-Tibetan-influenced style were produced during the Yongle reign, and the style continued into the sixteenth century with but little change or evolution. The soft folds in the scarf draped over the bodhisattva’s shoulders and arms and the loose pleats of the sarong-like undergarment are typical of works produced in the imperial workshops during the Yongle and Xuande reigns, as is the careful casting of the back.

The formulaic, six-character inscription reading Da Ming Xuande nian shi大明宣德年施, which is engraved at the center of the base’s flat top and which may be translated “Bestowed [during the] Xuande era [of the] Great Ming”, dates this sculpture to the Xuande reign (1436-1435) of the Ming dynasty, a period of great artistic refinement in China. Engraved after casting, inscriptions on such Tibeto-Chinese-style bronzes typically read from left to right, as seen here and end with the verb shi 施, in this context meaning “bestow”, rather than with the verb zhi 製, meaning “made”, which is typically seen in the imperial marks of porcelains of the same period.

A copper plate covers the open base of this hollow-cast sculpture. Held in place both by friction and red wax, the base plate conceals the sculpture’s interior from view and secures in place the dedicatory materials likely deposited within to enliven the image and grant it efficacy, the dedicatory materials probably including small scrolls and perhaps tiny sculptures, precious stones, fragments of textiles, and perhaps even seeds of auspicious plants. Engraved at the center of the base plate, a double-vajra with a stylized blossom at the crossing of the two arms symbolically shields and protects the sculpture and its probable contents.

A stylistically related sculpture from the Yongle period and representing Avalokiteshvara sold at Christie’s, New York, in March 2014. A sculpture kindred in subject, style, and general appearance to the present sculpture is in the collection of the Museum Rietberg, Zurich. And a stylistically related sculpture representing Seated Bodhisattva Tara in her “Green Manifestation” is in the collection of the Harvard Art Museums (1992.289).

Further highlights of the collection include a rare famille verte 'Yu Tang Fu Gui' teapot (estimate: £20,000-40,000), an elegant and fascinating tribute to the skills of porcelain decorators at the imperial kilns in the early Yongzheng reign; and a ‘peony’ ogee-form bowl and cover (estimate: £10,000–15,000), likely to have been made in the early 18th century within the Imperial Palace Workshops in the Forbidden City. Painted enamel was a European technique, which was introduced to China in the Kangxi period (1662-1722). The bowl emphasises the technical sophistication in the workshops and the cultural and artistic exchange between China and Europe in the 18th century.

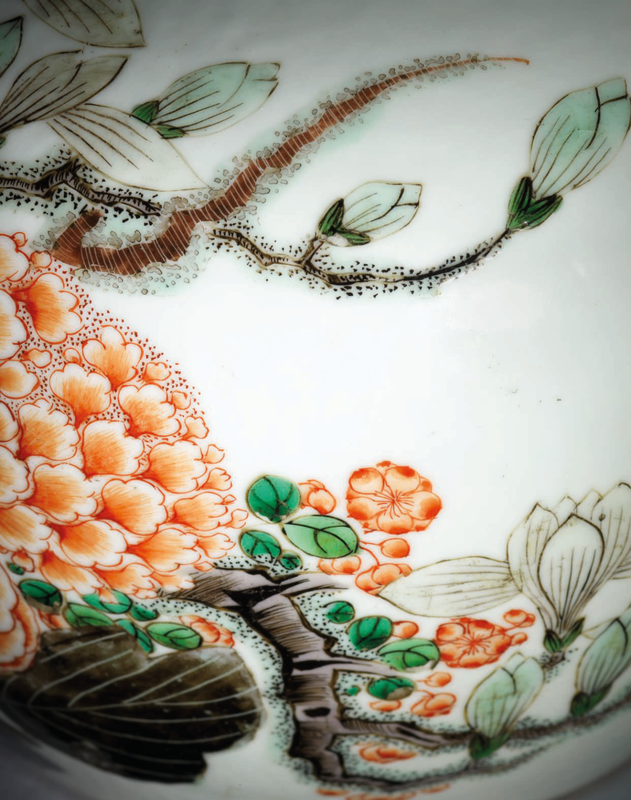

Lot 37. A very rare and large famille verte 'yu tang fu gui' teapot, Yongzheng six-character mark in underglaze blue within a double circle and of the period (1723-1735); 10 ½ in. (26.7 cm.) wide. Estimate GBP 20,000 - GBP 40,000 (USD 26,140 - USD 52,280). Price realised GBP 488,750. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018

The teapot is decorated to one side with a large flowering peony bloom in front of several branches of crab apple and magnolia. There is a bold inscription to the reverse readingyu tang chun fu gui ending with the signature Yue Qing followed by a seal mark yun ju. The cover is painted with bamboo and prunus sprays.

Provenance: Collection of the late Soame Jenyns (1904-1976), then by descent within the family.

This unusually large teapot bears a well-written six-character underglaze blue Yongzheng mark on the base, but it is clear that it dates to the early years of the Yongzheng period. A similarly-sized teapot decorated in a similar style and also with bold cursive large-scale calligraphy is in the collection of the Palace Museum Beijing (illustrated in Porcelains in Polychrome and Contrasting Colours, 38, The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, Hong Kong, 1999, p. 92, no. 84). Like the current teapot, the Beijing teapot is decorated in famille verte overglaze enamels with the black and red enamels predominating. The Palace Museum teapot, which comes from the Qing Court collection, does not have a reign mark, but has been dated to the Kangxi reign. In addition to the black enamel calligraphic inscription, the Beijing teapot bears two seals in dark red enamel at the end of the inscription reading xi and yuan 西 園 Western Garden. The same palette, bold use of black enamel, cursive calligraphy and two dark red seals can also be seen on two brush pots in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing (illustrated ibid., pp. 98-9, nos. 90 and 91). While the first of these brush pots is decorated almost entirely in black enamel in imitation of ink painting, with only very small areas of green and red, the second of the two brush pots is decorated using famille verte enamels in a similar way to that seen on the current teapot – with a somewhat greater use of the red and green enamels. The treatment of the lotus leaves on the brush pot is particularly reminiscent of the treatment of the peony leaves on the current teapot.

The floral decoration on the teapot is composed of magnolia, peony and crab-apple. This was a popular combination in the 18th century and thereafter, as the flowers combine to provide an auspicious rebus. White magnolia in Chinese is yulan 玉蘭, crab-apple is haitang 海棠, and peony is known as fuguihua 富貴花. Together these suggest the phrase yutang fugui 玉堂富貴 – ‘May your noble house be blessed with riches and honour’. The peony is known as the flower of riches and honour, while yu from magnolia and the tang from crab-apple provide a rebus for yutang or ‘jade hall’, which was a respectful way of referring to a wealthy household. The theme of the decoration is reinforced by the calligraphic inscription, which cover most of one side of the teapot and reads: yu tang chun fu gui玉堂春富貴 , followed by what appears to be a name: Yue Qing月卿 - literally ‘moon’ or ‘month’ and ‘minister’ or ‘high official’, which is probably a pen-name. In place of the separate xi and yuan (Western Garden) seals on the Kangxi teapot and brush pots, the current teapot has a single dark red seal reading: yun ju雲居 ‘Cloud Abode’ or ‘Cloud Dwelling’.

The reference to ‘Western Garden’ in the seals on the Kangxi items from the Palace Museum is not surprising, as there was a Western Garden in the imperial palace as early as the Han dynasty, and the tradition of such imperial gardens continued. Although the seals may instead be a reference to the famous ‘Elegant Gathering in the Western Garden’ 西 園 雅集 attended by a number of famous literati, which is believed to have taken place in AD 1087 in the garden belonging to Wang Shen (王詵 AD 1037-c. 1093). There are extant paintings of this elegant gathering attributed to Li Gonglin (李公麟 AD 1049-1106) and to the Southern Song artist Liu Songnian (劉松年). It is, however, more difficult to identify with any certainty the reference intended by the seal Yunju ‘Cloud Dwelling’ on the current teapot. It is possible that this is a Buddhihst reference. There was a Yunju temple with a stone pagoda at Fangshan in the Beijing area from the Tang dynasty. Indeed, its stone pagoda, built in AD 711, still stands. Records indicate that the 10th century Northern Song Chan Buddhist 44th Generation Patriarch Dharma Master Dao Qi (道齊 ‘Consonant with the Way’ AD 929-997) was associated with Yunju Monastery. The Master belonged to the Jin family, which came from Hongzhou 洪州, but during his lifetime he served as abbot of three different monasteries, the last of which was the Yunju Monastery. In one of his writings Master Dao Qi notes: ‘Cloud Dwelling [mountain] is lofty and steep; Lions makes it their abode.’ The ‘lions’ were a reference to high ranking members of the sangha(religious community) known for their great virtue. The Ming dynasty literatus Dong Qichang 董其昌 (1555-1636), who also had links with Chan Buddhism, is believed to have added an inscription to the exterior of one of the nine rock caves on Stone Sutra Mountain (Shijingshan 石經山) near Cloud Dwelling Monastery during an excursion to the area with other luminaries in AD 1631. The only recorded artist who appears to have taken a name related to Cloud Dwelling is the court artist Zheng Zhaofu 鄭昭甫, who was active during the early Ming dynasty Hongwu reign (1368-98), and who called himself Yunju shanren (雲居山人 Hermit of Cloud Dwelling). Further research may help to clarify the intended reference of the Yunju seal. As the teapot is decorated in a manner closely associated with ink painting and calligraphy, the reference is most likely to be an artistic or literary one.

It is interesting to note the links to and subtle developments from Kangxi style on this early Yongzheng teapot. The painting style of the overglaze iron-red areas of the decoration have great delicacy and the use of a fine brush can be seen. The style is in contrast to the normal Kangxi use of iron-red. However, a move towards a greater delicacy in the painting of small blossoms using overglaze iron-red enamel can be seen on an elegant famille verte bowl in the collection of the Shanghai Museum, which does not bear a reign mark but has been dated by the museum to the Kangxi reign (illustrated in Zhongguo wenwu jinghua daquan, Taoci juan 中國文物精華大全--陶瓷卷, Taipei, 1993, p. 415, no. 843). The iron-red painting on this bowl more closely resembles that on the current teapot than does most other Kangxi enamel painting.

An earlier, less delicate, version of the distinctive waisted form of peony blossom seen on the current teapot can be found on a number of Kangxi porcelains, inclduing a wucai phoenix-tail vase in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing (illustrated in in Porcelains in Polychrome and Contrasting Colours, 38, The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum, op. cit., p. 137, no. 125), and on a large handsome Kangxi dish in the Baur Collection, Geneva (illustrated by John Ayers in Chinese Ceramics in the Baur Collection, volume 2, Geneva, 1999, p. 30-31, no. 155). The fact that this form is generally associated with the Kangxi reign, albeit in a less delicate form, provides another reason to date the current teapot to the early years of the Yongzheng reign.

The delicate black speckles under a pale green enamel which surround and enhance the magnolia branches on the current teapot are reminiscent of the use of a similar decorative device, which appears regularly on fine Kangxi famille verte porcelains but can also be seen around the magnolia branches on a vase with six-character Yongzheng underglaze blue mark, decorated in fine famille verte enamels in the collection of Sir Percival David (illustrated by Rosemary Scott in Elegant Form and Harmonious Decoration – Four Dynasties of Jingdezhen Porcelain, London, 1992, p. 136, no. 154 – see right-hand image).

This rare teapot from the collection of one of the great British scholars of Chinese art, Soame Jenyns, is an elegant and fascinating tribute to the skills of porcelain decorators employing famille verte enamels at the imperial kilns in the early Yongzheng reign.

Lot 20. A rare and finely-decorated painted enamel 'Peony'-form bowl and cover, 18th century; 5 in. (12.6 cm.) diam. Estimate GBP 10,000 - GBP 15,000 (USD 13,070 - USD 19,605). Price realised GBP 428,750. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018

The bowl and cover are exquisitely painted to the sides with elaborate peony blooms growing from leafy stems in subtle tones of pink, purple and yellow on a white ground, the top of the cover is decorated with fruiting grape vines. The interiors and base are enamelled in lilac.

Provenance: Collection of Mr. & Mrs. Alfred Clark (1873-1950 and 1890/1-1976), no. 37.

Collection of the late Soame Jenyns (1904-1976), then by descent within the family.

Literature: International Exhibition of Chinese Art: Catalogue and Illustrated Supplement, London, 1935-1936, p. 187, no. 2195 and illustrated p. 203, no. 2195.

Transactions of the Oriental Ceramics Society, 1963-64, vol. 35, London, 1965, p. 71, no. 337 and illustrated plate 109, no. 337.

Soame Jenyns and Margaret Jourdain, Chinese Export Art in the Eighteenth Century, London, 1967, p. 132, no. 123.

Exhibited: International Exhibition of Chinese Art, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1935-1936, cat. no. 2195, ser. no. 2590

The Arts of the Ch'ing Dynasty, Oriental Ceramics Society Exhibition, London, 1964, no. 337.

Note: Painted enamels were known as ‘foreign enamels’. The technique was developed in Europe in Flanders at the borders between Belgium, France and Netherlands. In the late 15th century the town Limoges, in west central France, became the centre for enamel production. As the maritime trade flourished between East and West, enamels were introduced to China via the trading port Canton (Guangzhou). The Qing court then set up Imperial ateliers to produce enamelled metal wares in the Kangxi period (1662-1722). In the early period, due to insufficient technical knowledge, only small vessels were made, with limited palette and murky colours. By the late Kangxi period, a wider range of brighter and purer colours became available, resulting in clearer decorations and a higher level of technical sophistication.

The exceptional quality of painting on the current bowl and cover indicates that it is very likely to have been manufactured in the Imperial Palace Workshops in the Forbidden City in Beijing. Soame Jenyns himself notes this point in his publication co-authored with Margaret Jourdain, Chinese Export Art in the Eighteenth Century, 1967, p. 132, lot 123, where the current bowl is illustrated and captioned 'probably Peking work'. Archival documents indicate that certain painted enamel wares were gifted to the court by the Guangdong Maritime Customs Office in the early years of the Qianlong reign (1736-1695) and that these pieces had no marks. Is it noted that painted enamel wares from later in the period were made with Imperial reign marks.

The treatment of the two-tone turquoise and green-enamelled leaves displayed on the current bowl are reminiscent of Yongzheng period (1723-1735) enamels, particularly to peonies depicted on imperial porcelain wares. See for example a fine and rare famille rose 'peony' bowl of Yongzheng mark and period, sold at Christie's Hong Kong, 29 April 2002, lot 567.

These factors would place the current bowl in the early part of the 18th century and more specifically to the late Yongzheng-early Qianlong period.

In addition to the live auction, The Soame Jenyns Collection of Japanese and Chinese Art online will offer a superb selection of Japanese lacquer and porcelain including a rare and important Kutani fan box, dating to the Edo period (mid-17th century) (estimate: £20,000-30,000), alongside Kakiemon and Arita ceramics and porcelain from the Ming and Qing dynasties including wucai, blue and white, and enamelled ceramics.

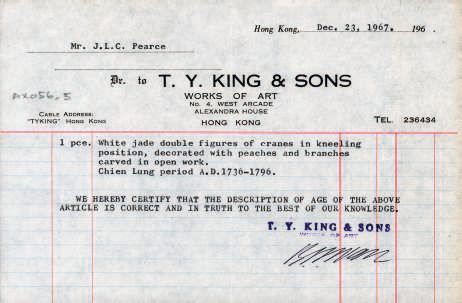

The highlight of the jade offering comprises the collection of Chinese hardstone carvings from the late John Pearce (1918-2017), purchased from the renowned Chinese art dealer, T. Y. King, in the 1950s and 1960s. Born into a family with a rich Hong Kong heritage, John Pearce was appointed an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) by George VI for his intelligence work during the Second World War. He was a prominent businessman and became a noted bloodstock breeder and racehorse owner. For forty years he lived at the Hong Kong Mandarin Oriental hotel, where he amassed an impressive collection of art. The collection is led by a large white jade cranes group from the Qianlong period (1736-1795) (estimate: £30,000-50,000). Skillfully executed as a larger and a smaller crane grasping a leafy peach branch, the details of their feathers are finely incised. The imagery of cranes and peaches portrays a wish for longevity, with both symbols closely associated with the Immortal, Shoulao, the God of Longevity. In Chinese mythology, peaches give long life to whomever consumes them, and hence are heavily featured in imagery associated with Immortals and other legendary figures. The collection also presents a greenish-white jade 'Mythical Beast' vase (estimate: £15,000–20,000). Dating to the 18th century, the impressive vessel is carved as a baluster vase which forms the body of a bixie, considered to have the power to dispel evil. Additional works from the collection include a greenish-white jade square-section brush pot, Bitong, 18th century (estimate: £10,000–15,000). Standing on four ruyi-form feet, each side is carved with a panel depicting a different scene of a seated scholar in a pavilion, a cowherd, a fisherman, and a farmer, all in a natural landscape.

Lot 214. A large white jade 'cranes' group, Qianlong period (1736-1795); 6 ½ in. (16.5 cm.). Estimate GBP 30,000 - GBP 50,000 (USD 39,210 - USD 65,350). Price realised GBP 68,750. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018

The large carving is impressively executed as a larger and a smaller crane, conjoined with their heads turned towards each other, each grasping a gnarled leafy peach branch in their beaks. Each bird is depicted with their wings folded at their sides and their legs tucked beneath them. The details of their feathers are finely incised. The stone is of an even white tone with a small russet inclusion to the underside.

Provenance: With T. Y. King & Sons, Hong Kong, 23 December 1967.

Note: he imagery of cranes and peaches portrays a wish for longevity, with both symbols closely associated with the Immortal, Shoulao, the God of Longevity. In Chinese mythology, peaches give long life to whomever consumes them, and hence are heavily featured in imagery associated with Immortals and other legendary figures.

Compare a smaller example dating to the 18th-19th century housed in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, accession no. 02.18.555 and one dated to the 18th century sold at Sotheby's Hong Kong, 7 April 2015, lot 3657. Compare also the stylistically similar water vessel carved as a single crane and peach from the James E. Sowell Collection sold at Christie's New York, 16 September 2015, lot 660.

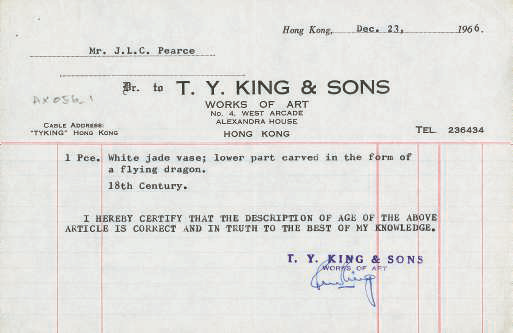

Lot 215. A greenish-white jade 'Mythical beast' vase, 18th century; 5 ¼ in. (13.3 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 15,000 - GBP 20,000 (USD 19,605 - USD 26,140). Price realised GBP 68,750. © Christie’s Images Limited 2018

The impressive vessel is carved as a baluster vase with forms the body of a bixie which is carved crouching with its head and tail lifted following the contour of the vase. Its wings are carved folded against its body and its legs are incised with an archaistic design. Its head is carved with an alert expression and its mouth open clasping a bowl. The stone is of an even pale tone with russet inclusions.

Provenance: With T. Y. King & Sons, Hong Kong, 23 December 1966.

Property from the Collection of the late Mr. J. L. C. Pearce (1918-2017)

Lot 213. A greenish-white jade square-section brush pot, Bitong, 18th century; 5 ¼ in. (13.3 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 10,000 - GBP 15,000 (USD 19,605 - USD 26,140). © Christie’s Images Limited 2018

The slightly tapered vessel is carved standing on four ruyi-form feet. Each convex side is carved with a panel enclosing a different scene of a seated scholar in a pavilion, a cowherd, a fisherman, and a farmer, all in a natural landscape. The stone is of an even pale tone with whitish inclusions.

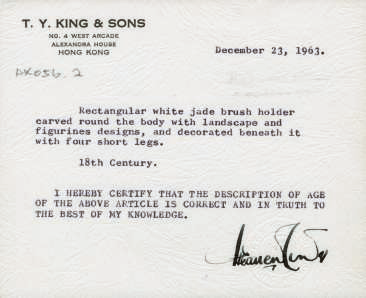

Provenance: With T. Y. King & Sons, Hong Kong, 23 December 1963.

Chinese Hardstone Carvings from the Late John Pearce (1918-2017) Collection

John Leitch Colmere Pearce was born in Hong Kong on 13 October 1918 into a family with a long connection in the Far East. His grandfather, the Rev Thomas William Pearce, spent nearly fifty years in China and worked as a missionary and translator. His father Thomas (Tam) Pearce was a prominent businessman in Hong Kong, and served as a Justice of the Peace and Chairman of the Hong Kong Jockey Club. John Pearce attended school at Charterhouse, and returned to Hong Kong to join the trading house, Hutchison International, in the mid-1930s.

At the outbreak of the Second World War, John Pearce joined the Royal Artillery, manning the anti-aircraft guns near Deepwater Bay. On Christmas Day 1941, Hong Kong surrendered to the Japanese after 18 days’ fierce fighting, during which Tam Pearce was killed in action and John was incarcerated in Sham Shui Po prisoner of war camp. In April 1942, he escaped through a sewage tunnel with three comrades, swimming into Chinese territory and eventually reaching Chungking after a journey of more than 600 miles. Rejoining the war effort as an intelligence officer, he assisted prisoners of war in escaping from Japanese camps. Major Pearce drew up an evasion map which was issued to all air forces operating in the Pacific, and was appointed an MBE (Member of the Order of the British Empire) by George VI for his intelligence work.

He returned to Hutchison International after the war, remaining on the board until his retirement in 1968. A steward of the Hong Kong Jockey Club, he was a regular at Sha Tin racecourse, where he often presented the Pearce Memorial Cup to the winner of a race run in memory of his father. Racing was his lifelong passion and he became a noted bloodstock breeder and racehorse owner. His chief ambition was to breed and run a winner of the Derby. He never did, but came tantalingsly close in 2006 when his horse, Dragon Dancer, came second by a short head. For forty years, until he was in his nineties, he lived in some splendour in a suite at the Hong Kong Mandarin Oriental hotel. Known for his courtesy, generosity and straight dealing, he once declined an invitation to join the Queen in her box at Royal Ascot because he had already agreed to meet a friend for tea.

Christie’s is delighted to present the John Pearce Collection of Chinese hardstone carvings, many of which were purchased from the renowned Chinese art dealer T. Y. King (金從怡) in the 1950s and 1960s.

A magnificent sancai and blue-glazed pottery figure of a guardian warrior dating to the Tang Dynasty (618-907) (estimate: £150,000 - 250,000) will also be offered. The guardian is modelled with an unglazed head, bearing a fierce expression. These large sancai tomb figures were the preserve of the Tang elite, and indeed some of the kilns producing them have been linked to the court. The current figure would have been particularly valuable since it has been decorated with a generous amount of blue glaze. In Tang times the cobalt used to create the blue glaze was imported into China and was expensive and used sparingly, unless the family commissioning the sancai ware belonged to the highest echelons of society.

Lot 13. A magnificent sancai and blue-glazed pottery figure of a guardian warrior dating to the Tang Dynasty (618-907); 29 3/8 in. (74.6 cm.) high. Estimate GBP 150,000 - GBP 250,000 (USD 196,050 - USD 326,750). © Christie’s Images Limited 2018

The guardian is modelled with an unglazed head which bears a fierce expression. His right hand is slightly raised and his left hand rests on his hip and he stands triumphantly on top of a demon with flailing arms on a raised base. He is dressed in full armour with masked horned epaulettes at the shoulder, and is splashed in blue, amber, green and cream glazes.

Provenance: Christie's New York, 27 November 1991, lot 291.

Christie's New York, 18-19 September 2014, lot 724.

The result of Oxford thermoluminescence test no. 566t37 is consistent with the dating of this lot.

This imposing figure would have been made to stand within the tomb of a member of the Tang dynasty elite. Magnificent sancai tomb figures, like the current example, flourished during the period from the late 7th to mid-8th century. One of the earliest tombs to contain sancai pieces was that of Li Feng, Prince of Guo (虢莊王 李鳳; AD 622-675), who was the fifteenth son of Emperor Gaozu (高祖 r. AD 618-26), founder of the Tang dynasty. Prince Guo was buried at the royal Xianling 獻陵 tomb in AD 675 (see Kaogu 考古, 1977, No. 5, pp. 313-26). By the first decade of the 8th century large sancaifigures were included in the tombs of royalty and nobility both at the capital Chang’an (modern day Xi’an) and at Luoyang, which served as the Eastern Capital in the Tang period. The inclusion of large sancai figures declined significantly following the An Lushan 安祿山rebellion of AD 755-63, which had a devastating effect on the empire, seriously weakened the dynasty, and led to the loss of the Western Regions.

In 1981 the undisturbed joint tomb of the Dingyuan General An Pu (定遠將軍 安普) and his wife was excavated at Longmen, Luoyang (see ‘The Tang Tomb of An Pu and his wife at Longmen, Luoyang’, Zhongyuan Wenwu, 1982, no. 3, pp. 21-26, and fig. 14). An Pu was descended from nobility of the Kingdom of Anxi and although he died at Chang’an in AD 664, aged 63, his wife, Lady He, did not pass away until 704. Their son An Jinzang, who became an official in the Music Office of the Bureau of Court Ceremonial, arranged for their joint re-burial at Luoyang in AD 709 with splendid furnishings, which included not only fine sancai figures, but carved limestone doors and an epitaph carved on a large square piece of limestone, which bears details of An Pu’s life as well as providing the date of the re-interment. In all, the tomb contained some 124 pottery items, amongst these the most impressive being the sancai camels and horses, and the three pairs of figures – two civil officials, two animal-bodied ‘earth spirit’ guardians, and two guardian warriors – also sometimes referred to as ‘lokapala’ or ‘Heavenly King’ - of similar type to the figure in the current sale.

The British Museum has in its collection a group of 13 sancai tomb figures which are believed to have come from the tomb of General Liu Tingxun, who died in AD 728 and was buried at Luoyang. Among these figures are the three pairs of figures which would have stood at the entrance to the tomb chamber (illustrated The British Museum Book of Chinese Art, J. Rawson (ed.), London, 1992, p. 143, fig. 93), including two guardian warriors - one of which is similarly clad in armour and helmet to the current figure. The British Museum figure also stands in a mirror image of the pose to that of the current figure, except that the museum figure is trampling an animal, while the current figure is trampling a demon.

Perhaps the most famous tomb figures are those from three of the royal tombs of the Qianling 乾陵 Mausoleum on Mount Liang 梁山, in Qian county, north-west of Xi’an. These are the tombs of Princess Yongtai (永泰公主 AD 685-701), daughter of Emperor Zhongzong (中宗 r. AD 705-710), who is believed to have been executed or forced to commit suicide by her grandmother, Empress Wu Zetian (武則天 d. AD 705), in 701, but was reinterred in the Qianling Mausoleum in 706 by her father after he regained the throne; Crown Prince Yide (懿德太子 AD 682-701), the only son of Emperor Zhongzong, who was executed or forced to commit suicide along with his sister and her husband in 701 on the orders of his grandmother, and who was also reinterred in the Qianling Mausoleum by his father in 706, and Crown Prince Zhang Huai (章懷太子 AD 653-684), sixth son of Emperor Gaozong (高宗 r. AD 649-683) and his second wife Empress Wu. He too was executed or forced to commit suicide on the orders of his mother Empress Wu Zetian after the death of Emperor Gaozong. He was also reinterred in the Qianling Mausoleum in 706 by his younger brother Emperor Zhongzong. Prince Zhang Huai’s tomb was excavated in 1971 and among the large sancai figures contained therein was a pair of guardian warriors in similar pose to the current figure (illustrated in National Treasure – Collection of Rare Cultural Relics of Shaanxi Province, Xi’an, 1998, pp. 230-1). Emperor Zhongzong’s determination to re-establish the nobility of the princess and the two princes can be seen not only in the posthumous titles he bestowed upon them but the grandeur of their new tombs with fine murals and impressive sancai figures. The contents of these tombs also reinforce the importance of sancai figures in the burial practices of the Tang royal house and aristocracy in the early 8th century.

The royal tomb sancai guardian warrior figures were armoured and helmeted in a similar fashion to the current figure. Figures such as these are often attired in a version of the zhanpao 戰袍 or battledress of imperial guards. On the upper body they wear a cuirass (breastplate and backplate fastened together), while the shoulders are protected by a type of paultron and the forearms by a type of vambrace, with greaves to protect the shins. These were worn with a knee-length coat. Armour similar to this is shown on imperial guards depicted in the murals on the walls of Princess Yongtai’s tomb (illustrated in Wenwu, 1964, no. 1, pl. VIf). As is frequently the case with guardian warriors of this type, the current figure stands with one hand resting on his hip and his other arm raised with hand curled around to hold a weapon such as a halberd, pike or spear. The weapon itself has not survived, probably because its shaft may have been made of wood.

As early as the third quarter of the 6th century, fierce guardians trampling on either animals or demons are found in a Buddhist context and in tombs. Guardian figures clad in armour and trampling demons appear at the Longmen caves 龍門石窟in Henan, where such figures can be seen on the wall of the Fengxiansi 奉先寺, dated to the 670s. A well-preserved painted wooden guardian figure in armour trampling a demon was excavated in 1973 at Astana near Turfan, Xinjiang Autonomous Region, from the joint tomb of Zhang Xiong (AD 584-633) and his wife née Qu (AD 607-688). It is likely that the guardian figure dates from the time of the wife’s burial in 688, when the tomb was enlarged (illustrated and discussed in J.C.Y. Watt (ed.), China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD, New York, 2004, p. 228, no. 180).

The guardian warriors are often called ‘lokapalas’ who appear at Indian Buddhist sites such as Bharhut in Madhya Pradesh as early as the 1st century BC (see R.E. Fisher, ‘Noble Guardians: The Emergence of the Lokapalas in Buddhist Art’, Oriental Art, vol. 41, no. 2 (Summer), pp. 17-24). The group of four guardians, or Heavenly Kings, who guard the four directions, became established in the 5th or 6th century. While four guardians appear on the walls of Cave 285 at Dunhuang (dated to AD 538), Chinese guardian warriors usually appear in pairs, both at Buddhist sites and in tombs. It has been suggested by some scholars that the Chinese guardian warriors are based not on lokapalas, but on dvarapalas – entryway guardians, although these latter figures are not normally depicted in armour (see J.C.Y. Watt (ed.), China: Dawn of a Golden Age, 200-750 AD, op. cit., p. 330). Both the dvarapalas and the Chinese guardian warriors are, however, characterised by the fierce expressions and threatening poses. This is in keeping with the protective role of the guardians, who, in the case of the Chinese tomb figures, stood at the entrance to the tomb chamber and repelled evil spirits.

Where the two guardian warrior figures from a tomb have been preserved together they are usually depicted in mirror image of each other’s stances. They are usually similarly dressed, but sometimes can wear different helmets and accessories – for example one may have an extravagant horned headdress and flames on the shoulders, and the other have a military helmet, like that worn by the current figure. A pair of figures of – one of each type, slightly smaller in size than the current figure - was excavated in 1955 from Hansenzhai village 韓森寨村, Xi’an, Shaanxi province (illustrated National Museum of Chinese History, A Journey into China’s Antiquity, vol. 3, Sui Dynasty-Northern and Southern Song Dynasties, Beijing, 1997, no. 184).

These large sancai tomb figures were the preserve of the Tang elite, and indeed some of the kilns producing them have been linked to the court. The current figure would have been particularly valuable since it has been decorated with a generous amount of blue glaze. In Tang times the cobalt used to create the blue glaze was imported into China and was expensive. It was thus generally used sparingly, unless the family commissioning the sancai ware belonged to the highest echelons of society, as would have been the case for the current figure.

The sale will also present outstanding examples of huanghuali furniture including a rare pair of huanghuali horseshoe-back armchairs, Quanyi, (17th to 18th century) (estimate: £100,000-200,000), alongside important archaic bronzes and works by leading modern Chinese painter Qi Baishi (1863-1957).

Lot 47. A rare pair of huanghuali horseshoe-back armchairs, Quanyi, 17th-18th century. Each 38 ¾ in. high x 26 ½ in. wide x 19 ¼ in. deep (98.5 x 67.3 x 49 cm). Estimate GBP 100,000 - GBP 200,000(USD 130,700 - USD 261,400).

On each chair the sweeping crest rail terminates in outswept hooks above shaped spandrels, and forms an elegant curve above the S-shaped splat carved with a ruyi-head roundel enclosing confronted chilong dragons and flanked by shaped spandrels. The rear posts continue to form the back legs below the rectangular frame above shaped, beaded aprons and spandrels carved in the front with a stylised scroll. The legs are joined by stepped stretchers and a foot rest above a shaped apron.

Provenance: Property from a Distinguished Private Collection.

Note: For a discussion on this shape of chair, see R.H. Ellsworth, Chinese Furniture: Hardwood Examples of the Ming and Early Ch'ing Dynasty, New York, 1971, pp. 86-87, and Wang Shixiang, Connoisseurship of Chinese Furniture: Ming and Early Qing Dynasties, Hong Kong, 1990, pp. 43-45.

Examples of this popular form crafted from huanghuali include a pair with carved ruyi heads on the splats, illustrated by Wang Shixiang and Curtis Evarts in Masterpieces from the Museum of Classical Chinese Furniture, Chicago and San Francisco, 1995, p. 56, no. 26, and later sold at Christie's New York, 19 September 1996, lot 99. A single huanghuali horseshoe-back armchair, carved in a similar fashion, is illustrated by R.H. Ellsworth in Chinese Furniture: One Hundred Examples from the Mimi and Raymond Hung Collection, New York, 1996, pp. 68-9, no. 14, where it is dated to the late Ming dynasty, ca. 1600-1650.

The auctions will be held during Asian Art in London 2018 (AAL), which takes place from 1st to 10th November.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_dcd32f_telechargement-32.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_0d4ec9_telechargement-27.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_fa9acd_telechargement-23.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_9bd94f_440340918-1658263111610368-58180761217.jpg)