Christie's Classic Week totals $79.5 million, Old Masters sales set 5 new world auction records

Jan Sanders van Hemessen (Hemessen c. 1504-1556 Antwerp), Double portrait of a husband and wife, half-length, seated at a table, playing tables. Oil on panel, 43 ¾ x 50 3/8 in. Estimate: $4,000,000 - $6,000,000. Price realized: $10,036,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

NEW YORK, NY.- The top lot Classic Week was Jan Sander van Hemessen’s ‘Double portrait of a husband and wife, half-length, seated at a table, playing tables’, which sold for $10,036,000, earning a new world auction record for the artist and a new record for an early Netherlandish painting. Other top lots included Annibale Carracci’s ‘The Madonna and Child with Saint Lucy and the Young Saint John the Baptist’ which sold for $6,063,500, earning a new world auction record for the arist. Additionally, Lorenzo Monaco’s ‘The Prophet Isaiah’ realized $3,615,000, which earned a new world auction record for the artist.

Lot 26. Annibale Carracci (Bologna c. 1560-1609 Rome), The Madonna and Child with Saint Lucy and the Young Saint John the Baptist, oil on panel, 31 x 24 ¾ in. (78.8 x 62.7 cm). Estimate: $3,000,000 - $5,000,000. Price realized: $6,063,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Provenance: Sampieri collection, Bologna, possibly by the 1760s, from where acquired by

Gavin Hamilton (1723-1798).

Francis Basset (1757-1835), 1st Baron de Dunstanville and Basset, Tehidy, near Cambourne, Cornwall; Christie's, London, 8 May 1824, lot 41, as Ludovico Carracci (bought in), and by descent to his daughter,

Frances Basset (1751-1855), 2nd Baroness Basset, by descent to the son of her cousin,

John Francis Basset (1831-1869), by descent to

Arthur Francis Basset (b. 1873), Tehidy near Cambourne, Cornwall; Christie's, London, 9 January 1920, lot 88, as Ludovico Carracci (12 gns. to Everitt).

Anonymous sale; Phillips, London, 8 December 1987, lot 69, as Sisto Badalocchio, where acquired by the present owner.

Literature: (Possibly) M. Oretti, Marcello Oretti e il patrimonio artistico private bolognese: Bologna Biblioteca Comunale, MS. B.104, E. Calbi and D. Scaglietti Kelescian, eds., Bologna, 1984, p. 66, as Ludovico Carracci.

(Possibly) Descrizione italiana e francese di tutto ciò che si contiene nella Galleria del Sig. Marchese Senatore Luigi Sampieri, Bologna, 1795, as Ludovico Carracci.

(Possibly) G. Gatti, Descrizione delle più rare cose di bologna, e suoi subborghi, Bologna, 1803, p. 169, as Ludovico Carracci.

R. L. Feigen & Co., Seven Highly Important Pictures, New York, 1988, no. 3.

D. Benati, 'Dipinti sugli altari,' A. Benati and D. Benati, eds., La Parrocchia di Sassomolare, Quaderni del Circolo Culturale Castel d'Aiano, XIII, Castel d'Aiano, 1998, pp. 76-77.

D. Benati, 'L'oratorio di San Rocco: Il ruolo di Reggio nella prima attività di Annibale Carracci', Il seicento a Reggio: La storia, la città, gli artisti, P. Ceschi Lavagetto, ed., Reggio, 1999, p. 54.

D. Benati, D. DeGrazia and G. Feigenbaum, eds., The Drawings of Annibale Carracci, exhibition catalogue, Washington, D.C., 1999, p. 46.

D. Benati and C. Bernardini, I dipinti della Pinacoteca Civica di Budrio, Bologna, 2005, p. 192.

D. Benati and E. Riccòmini, eds., Annibale Carracci, exhibition catalogue, Milan, 2006, p. 186, no. 4.1 (cat. by A. Brogi).

A. Weston-Lewis, 'The Annibale Carracci Exhibition in Bologna and Rome', Burlington Magazine, CXLIX, 2007, p. 259.

Exhibited: New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection, 28 May-12 September 2010, no. 39.

Until 1585 Annibale Carracci had diligently worked in the family workshop, adhering to the style dictated by his cousin, Ludovico, who was head of the workshop, and by his elder brother, Agostino. From that date on, however, Annibale became ever more independent, accepting commissions beyond his native city of Bologna and experimenting with his own style, to great success. It was precisely within this early moment of experimentation and rapid ascendance, around 1587-88, that Annibale painted this extraordinary Madonna and Child with Saint Lucy and the Young Saint John the Baptist, his earliest work on panel.

The beautiful Saint Lucy kneels before the Virgin and Child, holding in her left hand a martyr’s palm and in her right the eyes that are her identifying attribute. Having promised to consecrate her virginity to God, Saint Lucy is said have been tortured and her eyes gouged when she refused a suitor. When her family came to prepare her body for burial, the saint’s eyes are said to have been miraculously restored. With a steady and determined gaze, Saint Lucy here presents her eyes on a golden platter to the Virgin and Child. With an encouraging hand on her shoulder, the angel points toward the platter, as does Saint John, who looks directly toward the viewer, as if affirming her sacrifice and asking us to bear witness.

In 1585, Annibale produced his superb Pietà for the Capuchin church in Parma (fig. 1). It was perhaps during this stay in the city, while completing that commission, that the young artist immersed himself in the work of Correggio, whose style would markedly inform his own in the following years. The serene figures in the Feigen Madonna and the tenderness of their interaction is reminiscent of Correggio’s Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine in the Musée du Louvre, Paris (fig. 2). Yet Annibale’s composition is more intimate and the figures are arranged closely within the picture plain. Treated by a lesser artist, this tangle of hands and limbs at the center of the composition might have become busy and confused, but Annibale’s design is effortlessly and gracefully resolved. Correggio's influence is plainly visible in Annibale’s own Mystic Marriage of Saint Catherine, painted around 1586 for Ranuccio Farnese and now in the Museo di Capodimonte, Naples, and equally so in his Madonna of Saint Matthew of 1587-88 in the Gemäldegalerie, Dresden (fig. 3). So evident, in fact, is the Parmese influence on Annibale’s work during this period, that when the Feigen Madonna last appeared on the art market in 1987, it was offered with an attribution to Sisto Badalocchio, a native of Parma (see Provenance). Richard Feigen was not alone in recognizing the painting as the work of the youthful Annibale; Donald Posner, Denis Mahon, Mina Gregori, Charles Dempsey and Erich Schleier all attested to its authorship (Brogi 2007, op. cit.).

Initially, the Feigen Madonna was thought to date slightly earlier in his career, around 1584-85, but its marked relationship to the aforementioned pictures from later in the decade has led to scholarly consensus on a dating of 1587-88 (Marciari 2010, op. cit.). As John Marciari notes, the infant Saint John at lower left, his head tilted and blond hair curling back from his forehead and temples, instantly recalls the angel in the foreground of the Madonna of Saint Matthew (loc. cit.). While the angel seems to hover between adult- and childhood, with his combination of muscular physicality and supple flesh, those same soft features – the rounded cheeks, pointed chin, and wide, dark eyes – in the Saint John signify his infancy. There are similarities, too, between the features of the Christ Child here and the faces of the putti in the Dresden picture.

Paintings on panel are rare in Annibale’s oeuvre, and this Madonna is the earliest known among them. The choice of support may again have been inspired by the works of Parmigiano and Correggio that Annibale had the opportunity to study in Parma and other Emilian cities (ibid.). Correggio’s Mystic Marriage, for example, was in Modena until the end of the 16th century (ibid.). Since examples for comparison on this medium are so few, the brushwork employed in the present painting is perhaps best compared to that in his Venus with a Satyr and two Putti in the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence (fig. 4), and the Madonna and Child in Glory with Saints, known as the San Ludovico Altarpiece in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna (fig. 5), both of circa 1589.

Despite its strong stylistic connection to Parmese and Reggian painting, this Madonna was most likely produced for a Bolognese patron. At least four early copies are known today, suggesting the painting must have hung in a location sufficiently prominent for it to be admired and desired by multiple patrons. According to the 1824 catalogue, where it was offered as by Ludovico Carracci, the painting was said to have been acquired from the 'Zampieri' (Sampieri) collection by the Scottish painter and dealer, Gavin Hamilton (see Provenance). Many of the Sampieri paintings were acquired by the French Viceroy, Eugène de Beauharnais, in 1811 and are now in the Pinacoteca di Brera. While it is not known when the painting entered the Sampieri collection, Marciari asserts it is 'hardly implausible to suggest' that it was commissioned by the Carracci’s great Bolognese patron, Abbate Astorre di Vincenzo Sampieri (ibid.). This painting’s presence within Bologna’s most celebrated and enviable collection at Palazzo Sampieri would explain the existence of numerous copies. Annibale’s Burial of Christ, now in the Metropolitan Museum, New York, and Ludovico Carracci’s Saint Jerome, formerly in the Feigen collection, both formed part of the Sampieri collection and similarly exist in multiple copies.

The painting was acquired by Francis Basset, 1st Baron de Dunstanville and Basset who began amassing his collection while on his Grand Tour in 1777-78. The artworks acquired on that trip were sent home on the ship Westmorland, which was infamously seized by privateers en route and sold to Spain (Marciari, op. cit.). He bought more pictures on his return to Italy a decade later and acquired more from dealers in London. The misattribution to Ludovico in the 1824 sale was presumably adopted by Hamilton when he acquired the painting from the Sampieri collection. If this is indeed the case, the Feigen panel could well be the half-length Madonna and Child with figures by Ludovico recorded in Palazzo Sampieri in the 1760s or ’70s by Marcello Oretti (loc. cit.; Marciari, op. cit.). Ludovico’s Madonna is likewise listed in a 1795 inventory of Palazzo Sampieri and again in a guide by Giacomo Gatti in 1803, but has long been considered lost (loc. cit.). Gatti’s guide was published after Hamilton’s death in 1798, when the painting would long since have left the Sampieri collection, so it is possible he was merely citing earlier listings of the collection. Hamilton was known, however, to commission copies of paintings he planned to buy as replacements for their owners. It is possible, then, that the painting Gatti described was a copy of the 'Ludovico' (Marciari, op. cit.).

Lot 10. Lorenzo Monaco (Florence 1370/75-c.1425/30), The Prophet Isaiah, inscribed 'ECCE VIGO COCIP' (center right, on the scroll), tempera and gold on panel, 7 ¾ in. diameter (19.7 cm. diameter). Estimate: $1,500,000 - $2,500,000 . Price realized: $3,615,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Provenance: Probably the Church of San Procolo, Florence, for the altar endowed by Antonio di Andrea del Pannocchia (died 1412/13), until the church was suppressed in 1778 (thought to be the original location of the Accademia Annunciation altarpiece to which this tondobelonged).

(Possibly) the Badia Fiorentina, Florence, by 1795 and before 1810 (where, according to a label on the reverse, the Annunciation altarpiece was found).

Alexis-François Artaud de Montor (1772-1849), Paris; (†) his sale, Schroth, Paris, 17 January 1851, lot 51.

Anonymous sale; Sotheby's, London, 8 July 1987, lot 20, where acquired by the present owner.

Literature: (Possibly) F. Bocchi and G. Cinelli, Le bellezze della città di Firenze, Florence, 1677, p. 389, as by an unknown artist (referencing the Annunciation altarpiece).

(Possibly) L. Lanzi, Storia pittorica della Italia dal risorgimento delle belle arti fin presso alla fine del XVIII secolo, Bassano, 1795-96, I, p. 19, as Giotto (referencing the Annuniciation altarpiece).

A.-F. Artaud de Montor, Peintres primitifs: Collection de tableaux rapportée d'Italie et publiée pa M. le chevalier Artaud de Montor, 3rd ed., Paris, 1843, no. 51, pl. 17, as Cimabue.

A. Schmarsow, 'Maîtres italiens à la galerie d'Altenburg,' Gazette des beaux-arts, ser. 2, no. 20, 1898, p. 502, as Antonio Veneziano.

O. Sirén, Don Lorenzo Monaco, Strasbourg, 1905, p. 44.

G. Pudelko, 'The Stylistic development of Lorenzo Monaco, I,' Burlington Magazine, LXXIII, 1938, p. 248, note 33.

W. and E. Paatz, Die Kirchen von Florenz, Frankfurt-am-Main, 1940-54, I, pp. 292, 315, no. 144, p. 316, no. 151; IV, pp. 694, 700, no. 31 (referencing the altarpiece).

M. Eisenburg, The Origins and Development of the Early Style of Lorenzo Monaco, PH.D. dissertation, Princeton University, 1954, pp. 283-88, 310-11.

M. Eisenberg, 'Un frammento smarrito dell'Annunciazione di Lorenzo Monaco nell'Accademia de Firenze,' Bolletino d'arte, ser. 4, no. 41, 1956, pp. 333-35.

G. Previtali, La fortuna dei primitivi: Dal Vasari ai Neoclassici, Rome, 1964, p. 232.

M. Boskovits, Pittura fiorentina alla vigilia del Rinascimento, 1370-1400, Florence, 1975, p. 352.

M. Eisenberg, Lorenzo Monaco, Princeton, N.J., 1989, I, pp. 149-50, illustrated p. 150.

L. Kanter, Painting and Illumination in Early Renaissance Florence, 1300-1450, exhibition catalogue, New York, 1994, pp. 270-71, illustrated p. 271.

D. Gordon, The Fifteenth Century: Italian Paintings, National Gallery Catalogues, London, 2003, I, pp. 177, 186, note 64, fig. 20.

D. Parenti, in Lorenzo Monaco: A Bridge from Giotto's Heritage to the Renaissance, A. Tartuferi and D. Parenti, ed., exhibition catalogue, Florence, 2006, pp. 179-85, no. 27b, illustrated pp. 179 and 181.

D. Parenti, ‘Qualche approfondamento su Lorenzo Monaco e sulla Chiesa di San Procolo a Firenze,’ Intorno a Lorenzo Monaco: Nuovi studi sulla pittura tardogotica, D. Parenti and A. Tartuferi ed., Florence, 2007 pp. 20-31.

L. Kanter, Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection, New Haven, 2010, pp. 69-73, no. 20, illustrated.

S. Rossi, I pittori fiorentini del quattrocento e le loro botteghe : da Lorenzo Monaco a Paolo Uccello, Todi, 2012, p. 48.

Exhibited: New Haven, Yale University Art Gallery, Italian Paintings from the Richard L. Feigen Collection, 28 May-12 September 2010, no. 20.

Note: One of the leading painters in 15th century Florence, Lorenzo Monaco was born Piero di Giovanni and took the name Lorenzo Monaco, meaning 'Lorenzo the Monk', in 1390 when he joined the Camaldolese monastery of Santa Maria degli Angeli, Florence. He is known not only for his exquisite devotional paintings on panel but also for frescoes and illuminated manuscripts. The rhythmic, flowing lines that characterize his style lend his figures a sense of graceful movement, enhanced by a delicate and harmonious use of color.

This beautiful bust depicts the Prophet Isaiah, identifiable by the inscription on his scroll ECCE VI[R]GO CO[N]CIP[IET ET PARIET FILIUM](“Behold, a virgin shall conceive, and bear a son,” [Isaiah 7:14]). The tondo was recognized by Marvin Eisenberg in 1956 as one of the missing pinnacles from Lorenzo’s magnificent Annunciation altarpiece in the Galleria dell’Accademia, Florence (fig. 1, inv. no. 1890 n. 8458). The triptych's central scene is flanked by Saints Catherine of Alexandria and Anthony Abbot at left and Saints Proculus and Francis at right. The polyptych's exquisite figures are painted with remarkable grace, appearing almost to sway in front of the viewer, unrestricted by the gabled framing device that contains them. The throne is draped in cloth-of-gold shot with crimson which, combined with the gilt background, surrounds the Virgin in a celestial light. The Angel of the Annunciation hovers serenely on a series of clouds, yet the gold lines radiating from his legs and feet and the undulating drapery gives the impression of his being surrounded by swirling air. This sense of drama and movement justifies the pose of the Virgin who flinches, shrinking into her seat.

The pinnacle surmounting the central panel remains intact, with a tondo of the Eternal Father looking down and right, toward the Virgin, his left hand raised in a blessing and holding in his right a gilded globe. The decorative upper sections of the two lateral panels as they appear today, however, are reconstructions; their original troisfoil pinnacles were sawn off just above the heads of the saints. It is within one of those two missing pinnacles that this Prophet Isaiah would have been placed. That this roundel belongs to the Accademia triptych is universally accepted by scholars, but the matter of reconstructing its original placement, whether above the left- or right-hand wing, is less easily resolved. Eisenberg initially proposed that the Prophet Isaiah would have surmounted the right-hand panel, an assertion contradicted by Daniela Parenti. Based on the direction of the prophet's gesturing hand and gaze, Parenti places him above the left-hand wing, looking inward, toward the scene of the Annunciation (loc. cit., p. 179). Though, as Laurence Kanter notes, Isaiah points to his scroll, rather than to the scene beneath, and, even if he were within the left pinnacle facing right, his gaze would not rest on the central figures (loc. cit., p. 70). The light source, illuminating the prophet’s hooded cloak from left, corresponds with that in the right-hand panel, in which Saints Proculus and Francis are similarly lit from left (ibid.). But even this correlation cannot be relied upon as conclusive, since the left-hand panel is lit inconsistently, with Saint Catherine illuminated from right and Saint Francis from the front and slightly left (ibid.). Until the missing third tondo resurfaces Isaiah’s original intended position remains conjectural.

The matter of reconstructing the altarpiece’s predella is similarly unresolved. As the basis of his proposed reconstruction, Osvald Sirén used the predella of an Annunciation executed late in Lorenzo’s career (circa1420-24), for the Bartolini-Salimbeni chapel in Santa Trinità, Florence (fig. 2; loc. cit.). Matching the scenes represented in the lower section of that polyptych, Sirén united the Nativity from the Lehman Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (fig. 3); the Visitation and the Adoration of the Magi from the Courtauld Gallery, London; and the Flight into Egypt from the Lindenau-Museum, Altenburg. While these panels may indeed relate to one another, their relation to the Accademia Annunciationand to this Prophet Isaiah have since been rejected. Kanter subsequently proposed that the Funeral of an Unidentified Bishop Saint in the Musée des Beaux-Arts, Nice (fig. 4) may have belonged to the Accademia altarpiece. Kanter believes that the Funeral scene was likely painted by the young Fra Angelico, working in Lorenzo Monaco’s workshop (Kanter 2010, op. cit.). He argues that the unusual iconography implies the saint in question was not regularly depicted. The bishop Saint Proculus would fit just this description and his being the eponymous saint of the Florentine church which initially housed the Accademia Annunciation “may be more than a tantalizing coincidence” (ibid.). The mourners wear the habits of Camaldolese monks, a reformed Benedictine order, an illusion, Kanter suggests, to the fact that Saint Proculus’ remains were interred in a Benedictine monastery (ibid.).

The first mention of this Prophet Isaiah as an object independent from the altarpiece came in 1843 when it was published in the catalogue of Alex-François Artaud de Montor (loc. cit.). The author had included an engraving of the work which, along with eight other paintings from his collection, he attributed to Cimabue. A pioneer in collecting Early Italian paintings, prior to the Leopoldine and Napoleonic suppressions, Artaud de Montor had amassed a collection of some 108 works by 1810, dating from the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries (Kanter op. cit.). Publishing the painting in 1898, August Schmarsow proposed an attribution to Paolo Veneziano (loc. cit.) but it was Osvald Sirén in 1905 who, on the basis of that same catalogue engraving, recognized the prophet as the work of Lorenzo Monaco. Misreading the last letters of the prophet’s scroll as [S]CO CIP[RIANO], Georg Pudelko identified the subject as Saint Cyprianus (loc. cit.). He suggested it may have belonged to Lorenzo’s Coronation of the Virgin, painted for the Camaldolese monastery of San Benedetto fuori della Porta Pinti, Florence circa 1407-09 and now in the National Gallery, London (inv. no. NG1897). Pudelko’s theory was later disproved following Eisenburg’s reconstruction in 1954.

While it is not known when the two lateral pinnacles were removed, we do know that by 1812 the altarpiece entered the Accademia without them. A label on its reverse reveals that, at the time of the Napoleonic suppression the altarpiece was housed in the Badia Fiorentina, a Benedictine abbey and church in the center of Florence. The triptych is plausibly the “Nunziata” (Annunciation) described in the Badia in 1795-96 by Luigi Lanzi (loc. cit.), who mistook it for an early work by Giotto and thought it to be “una delle sue prime opera” (“one of his first works”). When the monastery was suppressed, many of the artworks housed there were removed and the abbey complex itself was separated out into houses, offices and shops. It was two years later that the altarpiece entered the collection of the Galleria dell’Accademia.

The question remains, however, as to where the altarpiece was located prior to the Badia. Walter and Elizabeth Paatz suggested the inclusion of Saint Proculus (the blond-haired warrior with a sword in the right-hand wing) might align it with an altarpiece mentioned by Francesco Bocchi and Giovanni Cellini in 1677 (loc. cit.). Bocchi and Cellini described “una Nunziata dipinta da incerto sul legno nel 1409” (“an Annunciation painted by an unknown on panel in 1409”) in the church of San Procolo, Florence. The inclusion of the church’s eponymous saint certainly gives weight to the Paatz’s argument and their hypothesis for the San Procolo provenance is widely accepted by scholars, with the exception of Eisenberg, whose doubts (based on the saint’s hagiography) have since been convincingly disproven by Kanter and Parenti. (Eisenberg 1989, op. cit.; Kanter 1994, op. cit.; Parenti 2007, op. cit.).

The exact date of this Prophet Isaiah (and of the Annunciation altarpiece as a whole) remains the subject of scholarly debate. Paatz and Kanter date it to 1409 (Paatz and Kanter 1994, op. cit.), while Mirella Levi d’Ancona and Miklòs Boskovits placed it a little later between 1410 and 1415 (M. Levi d’Ancona, ‘Bartolomeo di Fruosino,’ Art Bulletin, 1961, 43, p. 93; Boskovitz, op. cit.). Luciano Bellosi and Eisenberg, meanwhile, had initially considered it to have been painted earlier, settled on a date between 1415 and 1420 (loc. cit.). Parenti tentatively hypothesizes that the original inscription as described in 1677 may have been misread as MCCCCVIIII (1409) rather than MCCCCXIIII (1414) (Parenti 2006 and 2007, op. cit.). If such an error did indeed occur – whether during the transcription or due to damage obscuring an accurate reading – then this dating would align the Annunciation altarpiece with Lorenzo’s Coronation of the Virgin altarpiece of 1413 for the church of Santa Maria degli Angeli.

The top lot of from the Estate of Lila and Herman Shickman was Juan van der Hamen y León’s ‘Peaches, pears, plums, peas and cherries in wicker baskets, figs, plums and cherries on pewter plates, a boquet of tulips, blue and yellow irises, roses and other flowers in a Venetian crystal vase with terracotta and glass vessels and stone fruit on a stone ledge’, which sold for $6,517,500, a new world auction record for the artist. The other top lot within the sale includes Willem Kalf’s ‘A chafing dish, two pilgrims’ canteens, a silver-gilt ewer, a plate and other tableware on a partially draped table’, which realized $ 2,775,000, earning a new world auction record for the artist.

Lot 109. Juan van der Hamen y León (Madrid 1596-1632), Peaches, pears, plums, peas and cherries in wicker baskets, figs, plums and cherries on pewter plates, a bouquet of tulips, blue and yellow irises, roses and other flowers in a Venetian crystal vase with terracotta and glass vessels and stone fruit on a stone ledge, signed and dated 'Ju° vander hamen fat. 1629' (lower right), oil on canvas, 34 x 51 7/8 in. (86.4 x 131.8 cm.) Estimate USD 6,000,000 - USD 9,000,000. Price realised USD 6,517,500, new world auction record for the artist. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Lot 107. Willem Kalf (Rotterdam 1619-1693 Amsterdam), A chafing dish, two pilgrims' canteens, a silver-gilt ewer, a plate and other tableware on a partially draped table, signed 'w. KALF.' (lower right, on the front edge of the table), oil on canvas, 39 ¾ x 31 ¾ in. (101 x 80.5 cm.) Estimate USD 2,000,000 - USD 4,000,000. Price realised USD 2,775,000, new world auction record for the artist. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

The top lot of the Old Masters Paintings and Sculpture sale was a pair of parcel-gilt polychrome wood altarpiece reliefs attributed to Hans Klocker And Workshop circa 1495-1500, which achieved $362,500. Top works of sculpture include Rudolf (Ridolfo) Schadow’s White Marble Figure Of The Sandal Binder, which sold for $200,000 and a bronze figure of Neptune attributed to Benedikt Wurzelbauer, circa 1600, which totaled $200,000 against an estimate of $40,000-60,000. A still-life by Cristoforo Munari was the top painting, selling for $162,000 over an estimate of $60,000- 80,000, and a large group of European quartz and glass cameos, largely 18th, 19th and 20th century, soared above its estimate of $5,000-8,000 to achieve $156,250.

Lot 220. Attributed to Hans Klocker And Workshop (Active 1482-1500), South Tyrol, circa 1495-1500, A pair of parcel-gilt polychrome wood altarpiece reliefs depicting the Circumcision and the Adoration of the Magi, with a 'BUNDES DENKMALAMT / WIEN' sticker and stenciled in black '13'; the first: 30 x 31 ½ in. (76 x 80 cm.); the second: 29 ½ x 33 1/8 in. (75 x 84 cm.). Estimate USD 80,000 - USD 120,000. Price realised USD 362,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Provenance: Sold, Christie’s, New York, June 1, 1994, lot 70.

Literature: C. T. Müller, Gotische Skulptur in Tirol, Innsbruck and Vienna, 1976, figs. 155-159.

R. Kahsnitz, Carved Splendor: Late Gothic Altarpieces in Southern Germany, Austria, and South Tirol, Munich, 2005, pp. 208-221, no. 9.

Note: The present wood reliefs compare very closely to the figure of Christ on a donkey originally from the Church of the Assumption of Mary in Caldaro, South Tyrol, and today in the Museo Civico, Bolzano. In 1498, Hans Klocker was paid for the creation of the high altar of the same church, now dismembered, together with this Palmesel depicting Christ’s re-entry into Jerusalem. The head of Christ from the Palmesel, with its restrained gesture, sharp-edged and hard facial features echoes those of the present reliefs, particularly figures of two of the Magi facing Christ and the two flanking male figures in the Circumcision relief.

Hans Klocker was first mentioned in a letter of recommendation from the Bishop of Brixen in 1482 as ‘our faithful master Hanns Klöckl, sculptor…highly renowned for the faithfulness and artistry of his work’. Contracts and receipts tell us that the retable at St Leonard in Passeier is his work, as is the high altar at Caldaro and the Franciscan altar at Bolzano, dated to 1500. His surviving output shows that Klocker was one of the finest sculptors working in wood at this period, with an extraordinarily precise and distinctive carving style.

The relief of the Adoration of the Magi is based on an engraving of 1475 by Martin Schongauer. Klocker developed many of his figures after pattern engravings by Schongauer, as did countless other artists of his time.

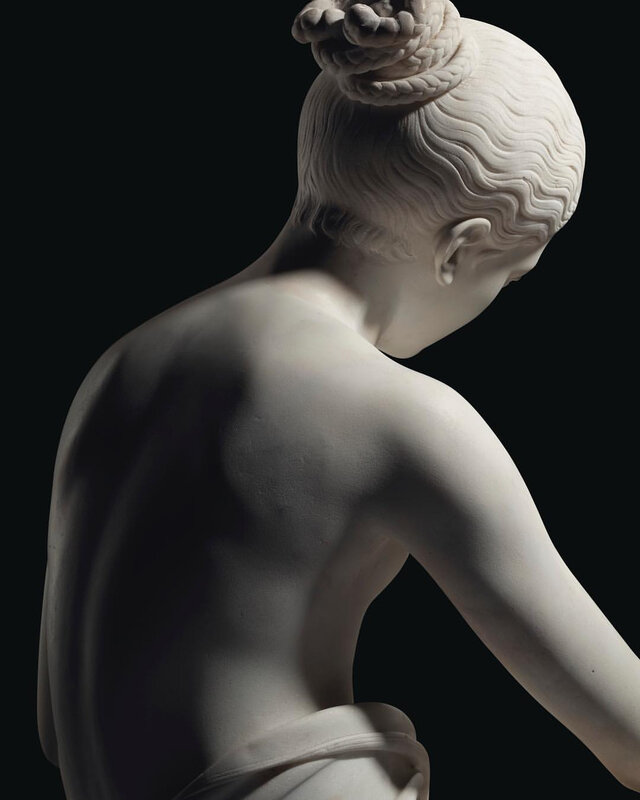

Lot 292. Rudolf (Ridolfo) Schadow (1786-1822), Rome, 1814. A White Marble Figure Of The Sandal Binder (Sandalbinderin). Signed and dated RUD: SCHADOW FEC: ROMAE / ANNO 1814, 50 in. (127 cm.) high. Estimate USD 100,000 - USD 200,000. Price realised USD 200,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Provenance: Private collection, New York, where acquired by the present owner, New York, in the late 1970s or early 1980s.

Literature: COMPARATIVE LITERATURE: D.C. Johnson, ‘Rudolf Schadows Sandalbinderin in Rom und Amerika,’ Forschungen und Berichte, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 1983, XXIII, pp. 113-122.

G. Eckardt, Ridolfo Schadow: Ein Bildhauer in Rom zwischen Klassizismus und Romantik, Cologne, 2000, pp. 30-31 and 82-86.

Note: Schadow was one of the most talented and original 19th century sculptors and The Sandal Binder was one of his most iconic compositions. It is a brilliantly-carved and conceived example of Northern neoclassicism, cool and emotionally restrained, The Sandal Binder is, at the same time, an incredibly intimate and sensitive portrait of a young girl. Until now, there were thought to be only four life-sized versions. The appearance of this sculpture is both exciting and significant as this version, signed and dated 1814, is, almost certainly, Schadow’s original version.

Schadow, the son of a famous sculptor and the brother of a famous painter, was raised in an intensely artistic and sophisticated milieu. His father, Johann Gottfried Schadow (1764-1850), after studying in Italy, was named Court Sculptor to the Prussian court at Berlin in 1788 and Secretary of the Prussian Academy of Art. For the next sixty years he produced hundreds of royal, ecclesiastical and public sculptural commissions, including the iconic Quadriga atop Berlin's Brandenburg Gate. Ridolfo Schadow’s sculpture, like his father’s, was formed by Italy and the staggering treasures of Greek and Roman Sculpture on view – as well as the lively Grand Tourist trade which brought Europe’s most important living sculptors to the Eternal City.

As stated, there are four other known life-size versions of Schadow’s Sandal Binder. There is also a plaster model, location unknown, which Eckardt dates to 1813/1814 (Eckardt, op. cit., pp. 82-86).

The first, not signed or dated, is described by Eckardt as possibly the original version, was bought by John Izard Middleton, who was in Rome in 1820 and it is documented at the Middleton Place plantation, South Carolina, by 1840 where it remains to this day (courtesy of the Middleton Place Foundation Archives). This version has, sadly, suffered considerable damage as it has been displayed outside for many years and was buried, to hide it from Union troops, at the end of the Civil War when they marched on Charleston and Middleton Place, together with its collections and library, was burned to the ground.

The second, signed Rudolph Schadow / fec: Romae. 1817, was seen by Crown Prince Ludwig I of Bavaria during his trip to Rome and was purchased and delivered to the Munich Glyptothek by 1819 and is now in the Neue Pinakothek (WAF B 24).

The third, signed Rudolph Schadow fecit. / Romae 1819 pro Henrico Patten / Westport Hibernia., was commissioned, along with Schadow’s Spinner (sold Sotheby’s, London, 8 July, 2010, lot 122), for Patten’s County Mayo estate and, eventually, ended up in an American private collection and was sold, Sotheby’s, London, 12 June 1986, lot 201W. It then went to the Galerie Westphal, Berlin and, finally, a private collection, Hamburg.

The fourth, signed Rudolph Schadow: / fecit Romae. 1820, was bought by King Frederick William III of Prussia and installed in the Gelben Marmorsaal of the Berlin Schloss by 1824. It is now owned by the Stiftung Preußishe Schlösser und Gärten and is on loan to the Friedrichswerderschen Kirche, Berlin (Skulpturensammlung 2822).

It is clear that Schadow was immensely proud of his marble. The Sandal Binder is prominently depicted in a fascinating group portrait by Schadow’s brother Wilhelm and now in Berlin’s Nationalgalerie. The sculptor Bertel Thorvaldsen is flanked, on the right, by a self-portrait of Wilhelm with his painter’s palette and, on the left, by his brother Ridolfo holding his chisel and with his Sandal Binder prominently displayed behind him. Thorvaldsen, a Dane who spent most of his working life in Rome, was, along with Antonio Canova, the most celebrated sculptor in Europe and, like Canova, helped popularize this severe, cerebral neoclassicism in late 18th and 19th century sculpture. The painting, dated 1815/1816, very likely depicts the present version of The Sandal Binder as the present version is the only one which can be definitively dated to before the picture was painted. As has been mentioned, the Middleton Place version, previously thought to be the original version, is neither signed nor dated. And it is also very unlikely that the Middleton Place version would have remained in Schadow’s studio from 1814 until 1820 when it was purchased by Middleton. With collectors and courts clamoring for a version of The Sandal Binder, would Schadow really have left his first internationally acclaimed masterpiece sitting in his studio and unsold for six years?

Intriguingly, there is a drawing of The Sandal Binder by Ferdinand Ruscheweyh, a German contemporary of Schadow’s who had visited his Roman studio, been impressed by The Sandal Binder and recorded it. The drawing is inscribed by Ruscheweyh: Rudolf Schadow in Marmore fecit Romae 1814 (Berlin Kupferstichkabinett, and illustrated in Eckardt, p. 83). Not only is this inscription almost identical to the inscription of the present marble but, as the Middleton Place version has no inscription and the inscriptions on the other three versions do not match at all and are considerably later, it seems likely that Ruscheweyh’s drawings depicts the present version.

The Sandal Binder was probably not a specific commission but an original composition inspired by Schadow’s studies of Antiquity and life in Rome. So it is interesting to speculate on the origins of this present version. Of the other versions: one was purchased for the grandest plantation in North America, another commissioned for an important collection in Ireland and the two others were purchased by the kings of Bavaria and Prussia. Who could have visited Schadow’s Roman studio first, before these other aristocrats and royals, and fallen in love with this Sandal Binder?

Lot 265. Attributed to Benedikt Wurzelbauer (1548-1620), circa 1600, A bronze figure of Neptune. Formerly a fountain, with printed paper label to underside Julius Böhler Munich and inscribed in ink E/97/0007, 29 in. (73.7 cm.) high. Estimate USD 100,000 - USD 200,000. Price realised USD 200,000. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Provenance: Private collection, Switzerland.

with Julius Böhler, Munich, 1998.

Literature: Apollo, CXLVII, 433, March 1998 (advertisement).

M. Schwartz, ed., European Sculpture from the Abbott Guggenheim Collection, New York, 2008, pp. 156-157, no. 82.

COMPARATIVE LITERATURE: H. Weihrauch, Europäische Bronzestatuetten, 15-18. Jahrhundert, Brunswick, 1967, pp. 325-328, figs. 396 and 399.

J. Chipps-Smith, German sculpture of the later Renaissance, c. 1520-1580, Princeton, 1994, pp. 198-244.

Exhibited: Blumka Gallery, New York, Collecting Treasures of the Past, New York, 26 January-11 February 2000, no. 44.

Note: Grandson and nephew of Pankraz and Georg Labenwolf, Benedikt Wurzelbauer (1548-1620) is best known for his work on public fountains. As a bronze caster rather than a sculptor, his works can be very different from one another, since the designs were most probably supplied by various artists. The genius of Wurzelbauer was however his ability to develop a consistent style through his casting technique. By far his most prominent work is the Fountain of the Virtues (1583-1589), which is still today one of the landmarks of the city of Nuremberg. Cast and signed by Wurzelbauer, this fountain is an emblem of early public art and civic allegory of good government; and it is reminiscent in its attention to details and extensive decoration to the style of Wenzel Jamnitzer.

Several versions of this Neptune bronze exist in museum collections, including the J. P. Getty Museum and the Huntington Art Gallery which both ascribe their cast to Wurzelbauer. In its many variations, this model exemplifies his combination of German Renaissance forms and Italian-inspired Mannerism which translate in Neptune’s slender musculature and undulating beard. Like the other versions, the present bronze was likely part of a domestic fountain. The intricate fineness of Neptune’s facial expression and the richness of the patina make it a particularly admirable example of German Renaissance sculpture.

Lot 254. Cristoforo Munari (Reggio Emilia 1667-1720 Pisa), Biscuits, porcelain and an earthenware pot on a silver charger with a glass of wine, books, a clock, jasmine blossoms and other vessels on a partially draped stone ledge, oil on canvas, 23 7/8 x 29 1/8 in. (60.6 x 74 cm). Estimate USD 60,000 - USD 80,000. Price realised USD 162,500. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Provenance: with Ugo Allegri, Brescia, from whom acquired by the present owner.

Note: Described by the 18th-century Florentine biographer Francesco Maria Niccolo Gaburri as 'an excellent painter in the depiction of kitchens, instruments, rugs, vases, fruit and flowers', Cristoforo Munari was born in Reggio Emilia, where he was a protégé of Rinaldo d'Este, Duke of Modena (reg. 1694-1737). In 1703 he moved to Rome 'where he served the Very Eminent Cardinal Imperiali and other princes and lords' (F.M.N. Gaburri, Vite de' pittori, Florence, c. 1730-40, p. 618) and settled in Florence some time after 1706, becoming part of the Medici court and working for, among others, Ferdinand, Cosimo III and Cardinal Francesco Maria de'Medici, for the latter of whom he decorated the Villa Lampeggi with trompe l'oeil still lifes.

Munari produced the present refined still life in the early 18th century, while he was working in Florence. The artist presents the viewer with an abundance of delicacies and precious porcelain vessels arranged on a green stone table. An unseen source illuminates the display from the left, bathing it in a cool light that causes some of the objects to shine like jewels against the dark background. Munari delights in the juxtaposition of brittle and crunchy biscotti, which are split and ready to be enjoyed with honey, with the smooth and shiny Delft and Chinese porcelain. Completing this symphony of fragility are the crystal vessels in the background, delineated according to Munari’s typical practice only the flickering light that reflects along their contours. The artist likely considered this technique to be one of his hallmarks, as he chose to depict himself holding a similar glass with a long, fluted stem in his 1710 Self Portrait (Galleria degli Uffizi, Corridoio Vasariano) as well as in the circa 1710-15 Still life with musical instruments (The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston). Resting on a pile of leather bound books, the clock, with its tortoise shell ornamentation and gilt-bronze mounts, may have actually been part of the Medici collection, and adds further elegance and sophistication to the scene.

We are grateful to Professor Francesca Baldassari for endorsing the attribution to Cristoforo Munari on the basis of firsthand inspection.

Lot 239. Largely 18th, 19th and 20th century, European, A large group of quartz and glass cameos. Estimate USD 5,000 - USD 8,000. Price realised USD 156,250. © Christie's Images Ltd 2019.

Some 19th century examples possibly by James Tassie; includes examples made from lava, glass, quartz, shell and coral; some examples Roman, from the 1-3rd century BC; also including several glass beads and one micromosaic.

Francois de Poortere, International Director, Head of Old Masters, comments, “We are thrilled with the strong results of all the Old Masters sales, which had 92% sell-through rate by value supported by competitive bidding from five continents. Several new world auction records were established, led by Jan Sanders van Hemessen’s Double portrait of a husband and wife, half-length, seated at a table, playing tables. The painting was sold from the collection of Frank Stella, realizing $10,036,000, and set a record for any early Netherlandish work of art at auction. Further records include Annibale Carracci’s The Madonna and Child with Saint Lucy and the Young Saint John the Baptist ($6,063,500) and Lorenzo Monaco’s The Prophet Isaiah ($3,615,000), both from the collection of Richard Feigen. The Estate of Lila and Herman Shickman also set new world auction records for still-lives by Juan van der Hamen y Leon ($6,517,500) and Willem Kalf ($2,775,000). Christie’s are honored to have been entrusted with works from the prestigious collections of Frank Stella, Richard Feigen and the Estate of Lila and Hermann Shickman, all of which ensured that today’s sales will remain memorable.”

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F68%2F17%2F119589%2F128925733_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F60%2F53%2F119589%2F128446261_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F77%2F19%2F119589%2F126247017_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F82%2F08%2F119589%2F122394483_o.jpg)