Sotheby's to offer Chinese Art from the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Florence & Herbert Irving Gift

NEW YORK, NY.- Sotheby’s will offer 300+ Chinese works of art originally gifted by philanthropists and renowned Asian art collectors Florence and Herbert Irving to The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as a highlight of their Asia Week sale series in September 2019.

In March 2015, The Met announced the gift of 1,275 Asian works of art from Florence and Herbert Irving – a donation that fundamentally transformed the holdings of the museum’s Department of Asian Art, on the occasion of its centennial. At the time of their gift, the Irvings realized that a full assessment of their collection would take time, and that there would undoubtedly be many pieces that would unnecessarily duplicate works already in the collection. For that reason, they agreed that The Met could sell any of the works in their gift so long as the proceeds would go towards future acquisitions. The present sale is a fulfillment of that visionary goal.

The full proceeds of Sotheby’s sales will go into an Irving acquisition fund, to be used by The Met’s Department of Asian Art to continue the Irving legacy by seeking out artworks to further enhance the comprehensive nature of the institution’s holdings of Asian art.

Sotheby’s will present over 120+ archaic to Qing dynasty jades along with porcelain, sculptures and objects for the scholar’s studio in a dedicated sale on 10 September, titled Chinese Art from the Metropolitan Museum of Art: The Florence and Herbert Irving Gift. The auction is led by a finely carved spinach-green jade brushpot, formerly in the collection of Alfred Morrison and kept at Fonthill, his famed English country house (estimate $500/700,000). Additional objects from the Irving Gift will be offered in the Saturday at Sotheby’s: Asian Art auction on 14 September.

Public exhibitions for all of Sotheby’s Asia Week auctions will open on 6 September in our New York galleries.

Angela McAteer, Head of Sotheby’s Chinese Works of Art Department in New York, commented: “It is a privilege to work with The Met this autumn to help bring these exceptional works to collectors worldwide. Our sales are representative of the Irvings’ exceptional taste in Chinese art, which features a strong emphasis on organic materials and works hewn from nature, as well as extraordinary Chinese jades produced during the reign of the Qianlong emperor.”

Maxwell K. Hearn, Douglas Dillon Chairman of the Department of Asian Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, said: "Florence and Herbert Irving were visionary and passionate collectors whose devotion and generosity have dramatically transformed the Museum’s holdings. We are deeply grateful that their gifts will enable us to continue to enhance The Met’s collection.”

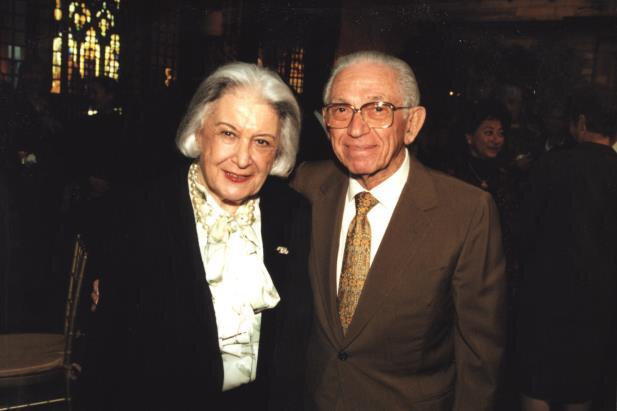

FLORENCE & HERBERT IRVING

Herbert and Florence Irving’s passion for Asian art began in the Asian galleries of the Brooklyn Museum of Art in New York. Initially their interest was focused on lacquer, and their first piece happened to be a Qianlong-period brush pot. Soon their wide-ranging art collection encompassed art not only from China, but also from Japan, Korea, India and Southeast Asia. As serious, scholarly collectors, they developed a close relationship with The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, where they held an important exhibition of their lacquer collection. The Met became in the end the home for many of their masterpieces.

The Irvings’ extensive relationship with The Met includes: Florence’s election as a museum Trustee in 1990, and election as a Trustee Emerita in 1996; the 1991 opening of the spectacular exhibition East Asian Lacquer from the Collection of Florence and Herbert Irving; the 1994 opening of the Florence and Herbert Irving Galleries for South and Southeast Asian Art, which gave The Met the most extensive display space for these arts anywhere outside Asia; the 1997 opening of the Florence and Herbert Irving Galleries for Chinese Decorative Arts, which added 3,000 square feet to the Asian Wing; their 2011 endowment of the position of Florence and Herbert Irving Curator of the Arts of South and Southeast Asia, which is currently held by John Guy; and their 2015 gift.

The Irvings’ 2015 gift of almost 1,300 works of art encompasses all of the major cultures of East and South Asia and virtually every medium explored by Asian craftsmen over five millennia. Areas of particular strength are Chinese, Japanese, and Korean lacquers, South Asian sculpture, Chinese jades and hardstones, scholars’ objects of ivory, rhinoceros horn, bamboo, wood, and metalwork, Japanese ceramics, and Chinese and Japanese painting. Taken together, this transformative gift fills gaps and extends the Met’s existing strengths in ways that will further elevate the Museum’s stature as one of the world’s premier collections of Asian art.

CHINESE ART FROM THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART: THE FLORENCE AND HERBERT IRVING GIFT

Auction 10 September

Lot 15. A Finely Carved Large Spinach-Green Jade ‘Immortals’ Brushpot, Qing Dynasty, Qianlong Period (1736-1795). Height 6 5/8 in., 16.9 cm. Estimate 500,000 — 700,000 USD. Lot sold 375,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the cylindrical body set over five ruyi-form feet, the sides deftly carved in high relief with nine immortals in a mountain retreat surrounded by rocky peaks, waterfalls, pines, and other vegetation, one side with six of the men gathered on a balustraded terrace, each with a long beard, voluminous robe, and a sprig of lingzhi, the terrace with a double-roof pavilion at one side and branching into two balustraded paths at the opposite side, one path zigzagging up the mountain to distant pavilion, the other winding behind a diagonal ridge of rockwork then crossing over a cascading waterfall and turning uphill to a temple with a large tripod censer at the entryway, three immortals gathered in front of the temple, two of them holding lingzhi and the third holding a scroll, a craggy ridge rising at a diagonal alongside the temple, on the opposite side of the ridge two deer resting amidst lingzhi beneath a willow and a wutong tree, the flat base centered with a slightly recessed circle, the stone a deep spinach-green color variegated with lighter green passages.

Provenance: Collection of Alfred Morrison (1821-97), Fonthill House, Tisbury, Wiltshire, no. 233.

Christie's London, 9th July 1980, lot 105.

Donald J. Wineman, New York, 24th August 1981, no. 85.

Collection of Florence (1920-2018) and Herbert (1917-2016) Irving, no. 352.

Note: This magnificent vessel belongs to a highly refined group of ‘figure-in-landscape’ brushpots, created at the height of the jade production in the Qianlong period (1736-1795). Portraying mythological and historical events, these brushpots are exquisitely carved in green or white jade. The green jade models, particularly the striking spinach-toned examples, appear to have been especially favored by the Qing court.

The present brushpot is an extremely luxurious item for the scholar’s desk and would have made a most desirable birthday gift in view of its popular theme of immortals surrounded by many auspicious elements such as deer and lingzhi. To create such an extravagant work of art, a high-quality boulder of substantial proportions would be essential. Such a boulder would not have been easily available before the Qianlong Emperor’s 1759 conquest of the Western Territories (xiyu), which gave him access to jade-rich Khotan. The number of surviving jade pieces of the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) from the period before 1759 is, in fact, conspicuously small compared to the immense quantity of jade artefacts produced thereafter.

Khotan (Hetian in Chinese), in modern Xinjiang province, was one of the most important trading oases along the Silk Road. Its geological setting was extremely favorable for the formation of high-quality nephrite. Renowned for its translucency and extreme toughness, Khotan jade was highly prized by the Qianlong Emperor who on several occasions expressed his admiration for this treasured stone in his poems inscribed on spinach-green jade items.

Tribute jade from Khotan was sent yearly to the imperial court, yet the Qianlong Emperor appeared to have asked occasionally for more than the stipulated quota. The best quality was kept for use at the Ruyi Guan (The Imperial Department of Production) while the rest was distributed among the various other production centers supervised by the imperial court, mostly situated in the Jiangnan area south of the lower reaches of the Yangzi river.

Although Khotan’s rich quarries were under strict imperial control and unauthorized mining was severely punished, as was repeatedly mentioned in the official records of the Qing dynasty, clandestine jade invariably found its way into the many local private workshops. Indeed, some jade masterpieces appear to have been manufactured in these workshops. Privately financed by the wealthy salt administrators in the Jiangnan area, these costly artworks would have been offered as tribute to the court, see Yulian Wu, Luxurious Networks: Salt Merchants, Status, and Statecraft in Eighteenth Century China, Stanford, 2017.

As trade flourished, court commissions became increasingly demanding, pushing the craftsmen’s technical and creative capacities to new heights, whereby they reached virtuoso skill in complex composition, as displayed on the current brushpot.

The splendid pictorial scene displayed on this vessel was probably sourced from a painting or book illustration. It was yet the craftsman’s challenge to transfer the picture onto the hard jade’s façade. To achieve this, the artisan ingeniously treated the carving like a continuous handscroll painting, distributing the various stages of the story over the vessel’s cylindrical surface.

Wielding the carver’s tool almost like a paintbrush, the artist has created depth and perspective through bold multi-layered relief sculpting, subtle outlines and shadow play by shallow etching. Threes and foliage are rendered naturalistically in openwork, forging illusory effects that draw the beholder into the scene.

The pictorial quality of this outstanding group of spinach-green jade brushpots is exemplified by a related vessel in the Sir Joseph Hotung Collection carved with various scenes from the Gengzhi tu [Pictures of tilling and weaving], and published in Jessica Rawson, Chinese Jade from the Neolithic to the Qing, The British Museum, London, 1995, cat. no. 29:18.

The Palace Museum in Beijing and the National Palace Museum in Taipei both possess spinach-green jade brushpots displaying related ‘figure-in-landscape’ scenes. The Palace Museum in Beijing has three pieces illustrated in Gugong Bowuyuan zang wenwu zhenpin quanji. Yuqi/The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum. Jadeware (III), Hong Kong, 1995, pls 168-170, depicting ‘A Literati Meeting in Xi Yuan’, ‘Six Hermits in Zhuxi’ (fig. 1) and ‘Seven Hermits in the Bamboo Grove’ respectively; and a fourth without feet, in Zhongguo yuqi quanji [Complete Collection of Chinese Jades], vol. 6: Qing, Shijiazhuang, 1991, pl. 278, illustrating a related scene.

A spinach-green jade ‘Six Hermits in Zuxi’ brushpot © The Collection of The Palace Museum, Beijing.

The National Palace Museum in Taipei has a brushpot without feet, included in the exhibition catalogue Huaxia yishu zhong de ziran jian/Viewing Nature in Chinese Art. A Special Exhibition of Select Artifacts from the Museum Collection to Celebrate the 2016 Tang Prize, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 2016, no. 28, carved with figures picking lotus blossoms. This vessel is also illustrated in Gongting zhi ya. Qingdai fanggu ji huayi yuqi tezhan tulu/The Refined Taste of the Emperor: Special Exhibition of Archaic and Pictorial Jades of the Ch’ing Court, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1997, cat. no. 58, together with two related examples without feet, no. 55 of smaller size, and no. 56 of somewhat larger size.

A spinach-green jade brushpot with a related figure scene, from the collections of E. L. Paget, Sir J. Buchanan-Jardine, Sir Bernard Eckstein and Sir Jonathan Woolf was included in the exhibition The Woolf Collection of Chinese Jade, Sotheby’s, London, 2013, cat. no. 45; and an example formerly in The Minnesota Museum of Art, St. Paul, Minnesota, is illustrated in Robert Kleiner, Chinese Jades from the Collection of Alan and Simone Hartman, Hong Kong, 1996, no. 13.

Compare also a spinach-green ‘Five Old Men of Suiyang’ brush pot, from the collection of A. Knight, sold at Christie’s London, 21st March 1966, lot 152, and again in our Paris rooms, 22nd June 2017, lot 9; and a ‘Wulao tu’ brush pot from the collection of Robert Napier, First Baron Napier of Magdala (1810-1890), sold in our London rooms, 7th November 2018, lot 19.

The present brush pot was formerly in one of the most important collections of Chinese art ever formed.

Alfred Morrison was an eclectic collector of European art, autographs and manuscripts. In the late 1850s, Morrison started to collect Chinese art and purchased many pieces from Lord Loch of Drylaw (1827-1900) and from the dealer Henry Durlacher (act. ca. 1843). Morrison’s country house at Fonthill near Tisbury in Wiltshire, was known to contain thousands of works of art. The present brushpot was among the artworks that were cleared from Fonthill House by order of Alfred Morrison’s grandson, John Morrison (1906-1996), First Baron Margadale of Isley, who sold the brushpot at Christie’s London, 9th July 1980.

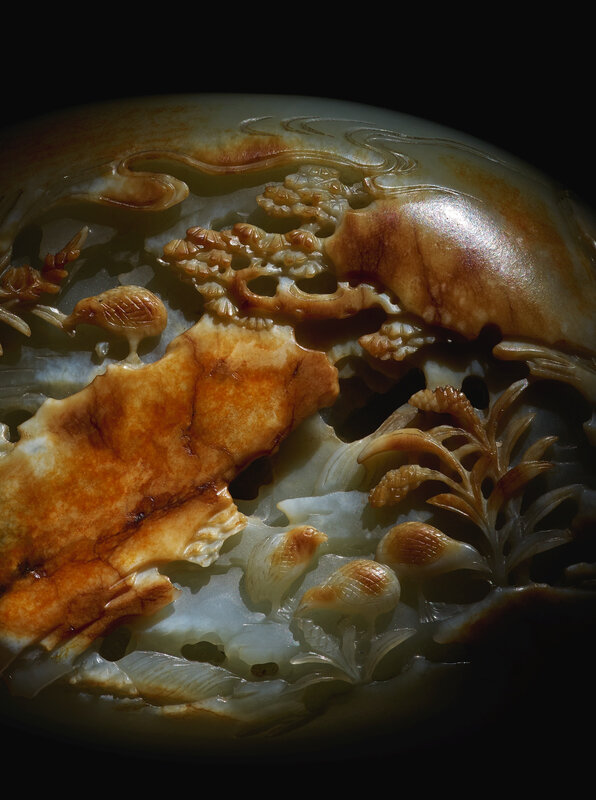

Lot 7. A Rare Celadon and Russet Jade ‘Quail and Millet’ Boulder, Qing Dynasty, Yongzheng-Qianlong Period (1723-1796). Length 6 1/8 in., 15.5 cm. Estimate 150,000 — 250,000 USD. Lot Sold 800,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the large ovoid stone deftly carved in high relief on one side with quails in a rocky enclave, three of the birds standing on a flat rock in the lower right corner of the composition pecking at leafing stalks of millet, rockwork rising at a diagonal overhead and serving as a perch for a fourth quail also eating millet, a gnarled tree growing nearby and a waterfall cascading in the deeply carved background, the opposite side carved with a river flowing between karsts, leafing and flowering branches peeking out from the sides of the hills, clouds swirling above, the stone a very pale seafoam green with orange-russet skin reserved for the coloration of the principal decorative features, wood stand (2).

Provenance: Christie’s London, 8th April 1978, lot 148.

Collection of Floyd and Josephine Segel.

Spink & Son, London, 8th April 1986.

Collection of Florence (1920-2018) and Herbert (1917-2016) Irving, no. 454.

The Qianlong Emperor advocated that jade mountains and carved panels should carry the spirit of paintings by famous past masters. It is recorded that a number of classical paintings from the imperial collection were ordered to be reproduced in jade. The motif of quails on this piece is reminiscent of bird-and-flower paintings made in the Song dynasty (960-1279), such as the anonymous hanging scroll Peace and Harmony, depicting quails and millet, in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, included in the Museum’s exhibition China at the Inception of the Second Millennium. Art and Culture of the Sung Dynasty, 960-1279, Taipei, 2000, cat. no. II-6.

Jade mountain carvings were kept in scholars’ studios where they provided a means of inspiration and escape from the regulated life of the court through their sense of ethereality and their subject matter. Quails, in China called anchun, are highly auspicious, since ‘an’ is a homophone of the word for peace. Depictions of quails among ears of millet are symbolic of abundance and express the wish for peace year after year (suisui ping’an).

Jade boulders carved with this motif are highly unusual, and no closely related example appears to have been published. A boulder carved with cranes, in the Sze Tak Tang Collection, was included in the Min Chiu Society exhibition Chinese Jade Carving, Hong Kong Museum of Art, Hong Kong, 1983, cat. no. 239; one with cranes and deer was sold at Christie’s London, 10th December 1990, lot 215; a boulder with monkeys, in the De An Tang Collection, was included in the exhibition A Romance with Jade, Palace Museum, Beijing, 2004, cat. no. 56, another was sold at Christie’s London, 6th June 1988, lot 3; and a further example carved with horses, was sold in these rooms, 23rd September 1995, lot 278. See also a much larger spinach-green jade boulder carved with chicks and inscribed with a poem composed by the Qianlong Emperor, sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 8th April 2011, lot 2812.

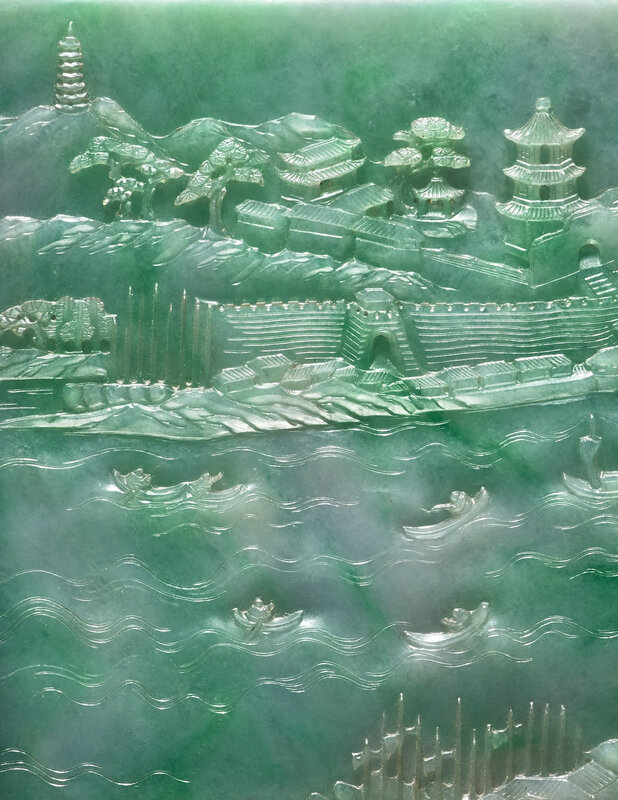

Lot 10. A White and Apple-Green Jadeite ‘Landscape’ Table Screen, Qing Dynasty, Qianlong Period (1736-1795). Width 8 3/8 in., 21.2 cm. Estimate 80,000 — 120,000 USD. Lot sold 1,076,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the horizontal rectangular panel finely carved to one side in relief with a riverscape, the water flowing diagonally from the upper right side and broadening toward the lower left corner, sailboats and fishing skiffs plying rippling waters, the near bank with docked boats and a small village with buildings and gardens, the opposite bank also with cabins and docked boats but backed by a massive fortified city wall stretching into the distance, an enormous temple complex including a stupa-form censer, pagoda, shrine, multi-tier temple, and monastic cells beyond the wall, a second pagoda rising from the mountains in the distance, the reverse unadorned, the stone an icy white with bright apple-green veins throughout and a small russet patch at the lower corner, hongmu stand (2).

Provenance: Collection of Sir Isaac (1897-1991) and Lady Wolfson.

Sotheby's London, 8th June 1982, lot 311.

Collection of Florence (1920-2018) and Herbert (1917-2016) Irving, no. 402.

Note: This table screen is striking for the brilliant green tone of the stone from which it was fashioned and is the pair to a table screen formerly in the collections of R.C. Bruce, H.M. Queen Marie of Yugoslavia, and Sir John Woolf, included in the exhibition International Exhibition of Chinese Art, Royal Academy of Art, London, 1935, cat. no. 1886, and now in the Woolf Collection, illustrated in The Woolf Collection of Chinese Jade, Sotheby's, London, 2013, cat. no. 10 (fig. 1). The natural striations and subtle variations in the stone's color, cleverly incorporated into the design of both screens to depict rippling water, appear to match. Furthermore, the two screens read like extracts from sections of a longer handscroll.

This table screen and its pair are also remarkable on account of their detailed depictions of a city, possibly showing two different views of West Lake in Hangzhou, Zhejiang province, the capital city of the Southern Song dynasty (1127-1279). The pair to this piece appears to depict Solitary Mountain (Gushan), an island in the West Lake connected to land through a series of bridges, while the present example may depict the tall Leifeng pagoda in the distance, and the Jingci temple at the foot of Nanping Hill. To this day, Hangzhou is renowned for its beautiful scenery, magnificent buildings and numerous bridges, and the tradition of sightseeing in Hangzhou can be traced back at least to the Tang dynasty (618-907). From the Song period through to the Qing dynasty, Hangzhou continued to attract numerous visitors, including the Qianlong Emperor, who visited the city during his Southern Inspection Tours. On the handscroll The Ten Views of West Lake, which was painted by Dong Bongda (1699-1769) before the Emperor's first southern inspection tour in 1751, a poem composed by the Emperor the year before captures his eagerness to travel there (Travelling with Art. Painting and Calligraphy Accompanying the Qianlong Emperor's Southern Tours, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 2017, cat. no. 3).

Jadeite table screens carved with such detailed sceneries of cities are highly unusual; a jadeite screen carved with a landscape in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, was included in the Museum's exhibition Jingtian gewu. Zhongguo lidai yuqi daodu/Art in Quest of Heaven and Earth. A Guide to Chinese Jades through the Ages, Taipei, 2011, cat. no. 7-5-2; and a larger pair of screens, in the National Museum of History, Taipei, was included in the exhibition Jade: Ch'ing Dynasty Treasures, Taipei, 1998, cat. nos 17 and 18. See also a white nephrite screen carved with Mount Riguan on one side and Baiyun Cave on the reverse, from the De An Tang Collection, included in the exhibition A Romance with Jade, Palace Museum, Beijing, 2004, cat. no. 63; and another from the Thompson-Schwab Collection, sold in our London rooms, 9th November 2016, lot 7.

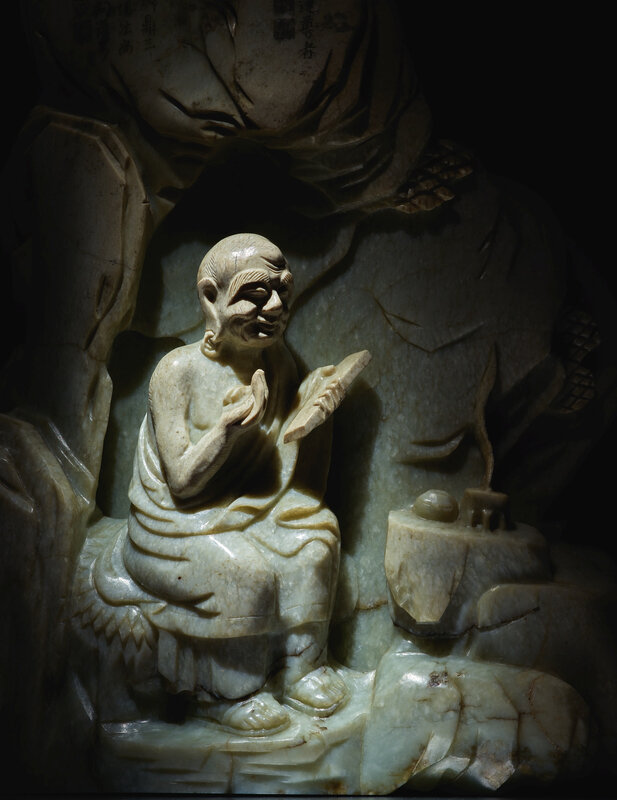

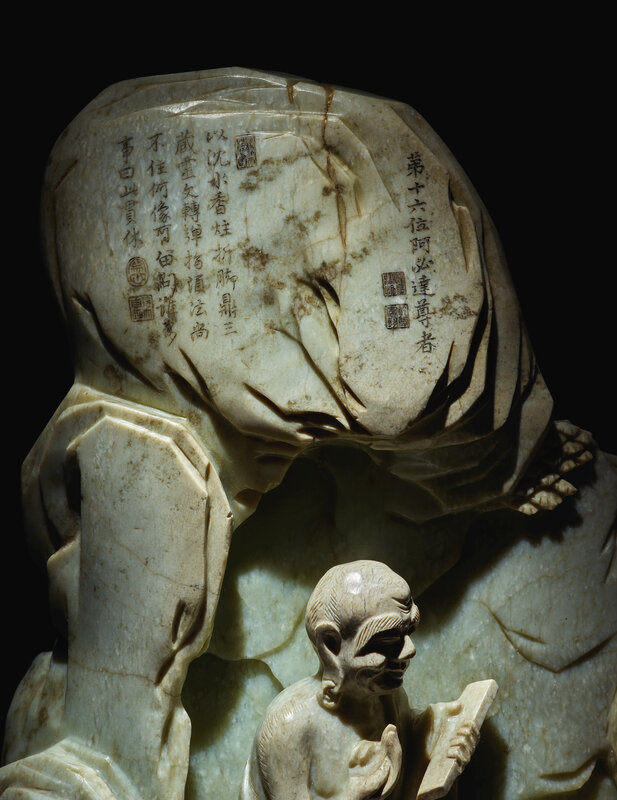

Lot 17. A Celadon Jade ‘Luohan’ Inscribed Boulder, Qing Dynasty. Height 9 5/8 in., 24.5 cm. Estimate 100,000 — 150,000 USD. Lot sold 740,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

carved after the Tang dynasty painter Guanxiu's iconic painting of Abheda, and inscribed with colophons composed by the Qianlong Emperor, the large vertical stone carved in high relief as a grotto sheltering Abheda, the adept carved mostly in the round and shown in three-quarter view seated on a boulder covered with a mat, the body wrapped in a loose robe secured at one shoulder and the feet in strap sandals, the right hand raised to the bare chest, the left hand holding a sutra, the face with long eyebrows brushing against the wrinkled cheeks, a pronounced cranium, and pendulous ears with a ring through the right lobe, a flat rock nearby serving as an altar supporting a small box and a censer emitting a wisp of incense smoke, the pronounced boulder overhead incised with two inscriptions each accompanied by seals, the reverse carved as a jagged rock face and incised at the top with a long inscription followed by two seals, the stone an opaque pale celadon turning to creamy beige in the areas of highest relief.

Provenance: Collection of Captain Vivian Buckley-Johnson (d. 1968).

Mount Trust Collection.

Collection of Floyd and Josephine Segel.

Spink & Son, London, 4th April 1986.

Collection of Florence (1920-2018) and Herbert (1917-2016) Irving, no. 453.

Exhibited: Victoria & Albert Museum, London, 1970.

Literature: Barry Till and Paula Swart, 'Mountain Retreats in Jade', Arts of Asia, July-August 1986, p. 52 and front cover.

Roger Keverne, ed., Jade, London, 1995, p. 145, fig. 41.

Note: The present sculpture, carved from a tall jade boulder, capitalizes on the material’s inherent qualities to create a towering stone grotto framing Abheda, who is seated in solitude with a sutra in hand and a censer burning nearby. The cavernous setting has been expertly crafted to give the impression of raw naturalism, while simultaneously providing the artisan with the requisite surfaces to render the arhat almost completely in the round and inscribe two accompanying texts above the figure and a third on the reverse of the boulder. As a result, the artist was able to faithfully translate Guanxiu’s (832-912) iconic painting of Abheda into three-dimensional form, to incorporate the Qianlong Emperor’s annotations on the painting, and to invigorate the nearly millennium-old image by sculpting it in luminous jade that captures light and shadow. By giving physical substance to the luohan, the sculpture invites viewers to walk around the artwork as they consider its religious significance. In each of these ways, the pictorial boulder follows the Qianlong Emperor’s standards for adaptations of classical paintings carved in stone.

This particular image of Abheda can be traced to the portrait series of the sixteen luohan painted by the Tang dynasty painter-poet-monk, Guanxiu, in 891. In it, the artist depicted the enlightened disciples with grotesque bodies, hunched backs, bushy eyebrows, and pronounced foreheads, as they had allegedly appeared to him in a dream. He then labeled each portrait with the Sinicized name of the arhat, according to the pilgrim Xuanzang’s (596-664) translation of the Fahua jin(Annotated Record of Buddhism). These bizarre portraits captured the imaginations of devotees, and the series was preserved in the Shengyin Temple near Qiantang (now Hangzhou) until 1861.

In 1757, the Qianlong Emperor visited the Shengyin Temple during his Southern inspection tour to study the portraits as an act of religious devotion. There is some debate as to whether the emperor viewed the original paintings or later copies, but in any case, he recorded that he had seen the masterpieces by Guanxiu and was inspired to personally study their contents and have their images proliferated. As a serious practitioner of Buddhism, the emperor noticed that the names on each of the portraits did not conform to the Sanskrit, so he annotated the paintings with the corrected names and reordered them according to his own teacher’s interpretation of their sequence in the Tongwen yuntong (Unified Rhymes). The emperor then penned two colophons on each painting, respectively eulogizing and reidentifying the luohan depicted. On the painting of the sixteenth luohan, Abheda, he also added a lengthy colophon describing his process of studying and reattributing each image.

Subsequently, the Qianlong Emperor commanded the palace painting master, Ding Guanpeng (act. 1708-ca. 1771) to copy the paintings and the new inscriptions that he had applied to them. Ding’s copies are now in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, and published Gugong shuhua tulu / Illustrated Catalog of Chinese Painting in the National Palace Museum, vol. 13, Taipei, 1994, pp. 183-214. Over the decades, the emperor had the images reproduced in additional media, including textiles and jades.

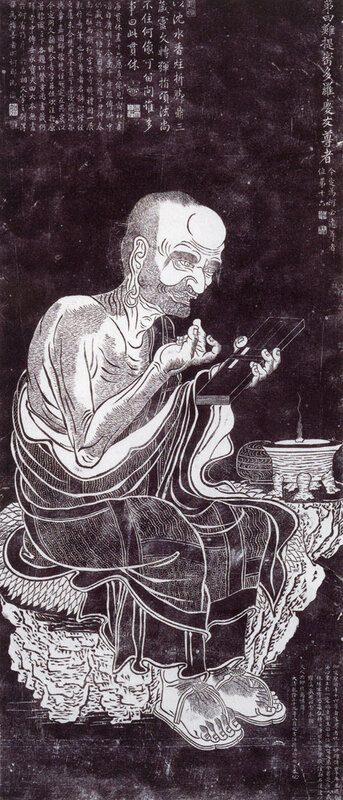

In 1764, the abbot at Shengyin Temple, Master Mingshui, instructed local stone engravers to copy Guanxiu’s paintings and the emperor’s colophons and seals. The sixteen engraved stone panels were installed on the sixteen sides of the Miaoxiang Pagoda in Hangzhou. Rubbings of the engravings were made by adherents as acts of piety, allowing the images and the emperor’s comments to proliferate further. The rubbings taken from it, as well as stone copies of the stele, are also preserved in museums, libraries, and private collections to this day (fig. 1). The pagoda and its carvings have since been moved to the Hangzhou Stele Forest.

Rubbing of Sixteen Arhats at Shengyin Temple. Courtesy of Special Collections, Fine Arts Library, Harvard University.

From the outset, the rubbings were widely admired. Knowing the emperor’s fondness for them, in 1778, the military governor of Shandong province, Guotai (d. ca. 1782), presented the Qianlong Emperor with a magnificent zitan folding screen set with black lacquer panels inlaid with white jade in imitation of the rubbings. The emperor was so impressed by the splendid gift that he had the Yunguanglou (Building of Luminous Clouds) of the Imperial Palace completely redesigned to accommodate and complement it. The illustrious screen remains part of the Qing Court Collection at the Palace Museum, Beijing, and was exhibited in the traveling exhibition The Emperor’s Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City, Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, 2010, cat. no. 49.

The present boulder closely follows the design of Guanxiu’s portrait, as preserved in the stele and rubbings. In the rocky overhang above the luohan, the Qianlong Emperor’s identification of the subject is recorded beside his eulogy on the painting. The colophon describing the emperor’s study of the paintings is inscribed on the reverse side. This would presumably have been made as part of a set of sixteen pictorial boulders, with the present one perhaps ranking as the most important due to its inclusion of the lengthy third colophon describing the emperor’s contribution to the legacy of Guanxiu’s paintings.

A strikingly similar jade boulder depicting the second luohan, Kanakavasta, accompanied by the two imperial colophons and seals is in the collection of the Wou Lien-Pai Museum and published in Rose Kerr et al., Chinese Antiquities from the Wou Kiuan Collection, Surrey, 2011, pl. 177 (fig. 2). See also a celadon jade boulder featuring the third arhat, Vanavasa, which generally follows Guanxiu’s design and is inscribed with the two imperial colophons, plus a six-character reign mark sold in our Hong Kong rooms, 27th April 2003, lot 22; and a related white jade boulder also carved with the sixteenth luohan, Abheda, inscribed with an imperial eulogy and dated to 1758, from the Crystalite Collection sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 30th May 2016, lot 3021. A white jade ‘luohan’ boulder, also from the Florence and Herbert Irving Collection, but carved with a design not derived from Guanxiu’s series, sold at Christie’s New York, 20th March 2019, lot 823.

Lot 20. A Massive Spinach-Green Jade ‘Dragon’ Washer, Qing Dynasty. Length 11 7/8 in., 30.2 cm. Estimate 100,000 — 150,000 USD. Lot sold 1,340,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's.

the naturally undulating sides boldly carved to the exterior with a pair of dragons striding toward the rim to contest a 'Flaming Pearl', each dragon with bulging eyes, the face framed by a bushy mane and long whiskers, the long muscular body covered in scales and snaking over and under splashing waves and swirling clouds, the surrounding ground covered with a dense network of spiraling cloud wisps, all above surging waves rising from the turbid sea covering the base, the interior hollowed and incised at the well with a forty-eight-character poem composed by the Qianlong Emperor in the jichou year, corresponding to 1769, followed by two carved seals, the stone a semi-translucent moss-green with a few areas of opaque beige, burlwood stand (2).

Provenance: Collection of Gamble North, Esq.

Sotheby's London, 18th June 1968, lot 150.

Sotheby's London, 13th November 1979, lot 236.

Ralph M. Chait Galleries, New York, 25th November 1980.

Collection of Florence (1920-2018) and Herbert (1917-2016) Irving, no. 214.

Note: The present washer, hewn from a massive jade boulder and carved to the exterior with powerful dragons writhing through swirling clouds and turbulent seas, can trace its form to an immense jade basin made 1265 and given to Khubilai Khan. The basin, sometimes referred to as the ‘Du Mountain basin', is the earliest known jade carving of this monumental scale (fig. 1). It is carved from a single block of dark blackish-green jade, and measures approximately half a meter deep and up to 182 cm wide. Similar to the present example, the sides are carved in high relief with dragons and other mythical creatures moving across a turbulent sea. Khubilai Khan placed the esteemed vessel in the Guanghan Hall of his pleasure garden, where it remained until the end of the Yuan dynasty when it was transferred to a Daoist temple and used for vegetables until being rediscovered in the 10th year of the Qianlong Emperor’s reign (1745) and moved back to the imperial gardens. The basin is now installed in the Round Fortress of Beihai Park, Beijing.

The jade ‘Du Mountain basin’, Yuan dynasty, 1265 © The Collection of The Palace Museum, Beijing

The Qianlong Emperor was so impressed by the basin that he had it cleaned and polished – a process that took four years given the scale of the work – and had three poems of admiration inscribed on its surface, dating to 1746, 1749, and 1773, respectively. Through cleaning and studying the basin, the Qianlong Emperor and his team of artisans developed a deep understanding of the vessel and the techniques involved in its creation. By 1753, the imperial workshop crafted a small jade washer in its image to present to the emperor. This delighted the Qianlong Emperor, who then commanded the artisans to rework the dragons on the Yuan dynasty basin according to those on the new, small washer. The exercise then inspired the Emperor to commission 40 further jade washers of this type: 20 of large scale, 10 of medium size, and 10 small versions.

Production of the Qianlong Emperor’s series of jade ‘dragon cloud’ washers began in earnest in 1759, when the emperor conquered Xinjiang and gained access to a steady and ample supply of jade from Khotan. The first large washer of the group, carved with nine dragons amidst clouds, was completed in the 34th year of the Qianlong reign (1769). The Emperor deemed the washer superior to its Yuan dynasty precedent, composed a laudatory poem to be carved on it, and installed it in the East Wing of the Qianqing Palace. Other washers from this series were placed in various halls throughout the palace. The imagery of the dragon and cloud – two entities that animate one another, and rely on their mutual interaction to realize their full power and potential – was a metaphor for good governance. Thus, when the Emperor would invite his officials to view the ‘dragon cloud’ washers, each viewer would be reminded that the empire needs virtuous, capable officials and a discerning emperor to appreciate their abilities.

Like the treasured ‘nine dragon’ washer in the Qianqing Palace, the present washer is similarly carved with a robust ‘dragon cloud’ design, and bears a poetic inscription attributing it to the 34th year of the Qianlong reign, corresponding to 1769. The exact dating of the Irving washer and its inscription have been the topic of some discussion, however, it is worth noting that the poem is recorded in Qing Gaozong yuzhi shiwen quanji / Complete Works of Poetry of Emperor Gaozong of the Qing Dynasty, Beijing, 1993, vol. 6, juan 81, p. 552. A second jade washer inscribed with the same poem remains in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing (inv. Gu 89417 Qinggong jiucang).

Additional Qianlong period washers of this type include a small spinach-green jade example with openwork details in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taipei, published in Masterworks of Chinese Jade in the National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1969, pl. 41; a small white jade washer in the same collection (inv. Guyu 2963), exhibited in Jade: From Emperors to Art Deco, Musée Guimet, Paris, 2016, cat. no. 124; a large spinach-green washer with five dragons sold in our London rooms, 10th November 2010, lot 316; a white and russet washer of comparable size to the present, but with three dragons and formerly in the collection of Alan and Simone Hartman, sold at Christie’s Hong Kong, 27th November 2007, lot 1504; and a white jade example with nine dragons sold in these rooms, 16th-17th September 2014, lot 28.

Lot 60. A Carved Limestone Head of a Bodhisattva, Sui Dynasty (581-618). Height 16 in., 40.7 cm. Estimate 80,000 — 120,000 USD. Lot sold 200,000 USD. Courtesy Sotheby's

the oval face with fleshy cheeks and a softly rounded chin, the bow-shaped lips drawn closed, the straight nose leading to the broad arched eyebrows, the eyelids partially lowered in contemplation, the face framed by pendulous ears to either side and an openwork diadem surrounding the ushnisha, the diadem comprising five large bejeweled roundels, each centered with a tassel, a double-chain of further jewels suspended between each roundel, the diadem secured by a sash with the loose ends draping behind the ears, traces of pigment, secured to a later base.

Provenance: Collection of Tejiro Yamamoto (1870-1937).

Alice Boney, New York, 3rd February 1983.

Collection of Florence (1920-2018) and Herbert (1917-2016) Irving, no. 860.

Note: This stone head is sumptuously carved with fleshy cheeks, broad arched brows and a large straight nose that leads the eye down to the plump lips. Its features exemplify a crucial sculptural transition from the linear and structured depictions of bodhisattvas in the preceding Northern Qi (550-577) and Northern Zhou (557-581) periods to the fully rounded and fleshy forms of the Tang dynasty (618-907). Its oval face and idealized expression, which exude deep spirituality, display an early attempt at naturalism, while its richly carved crown with suspended beads and floral diamonds is reminiscent of the stylized aesthetic of the preceding dynasties.

The Sui dynasty unified China in 589 after a long period of cultural, political and military disunion, which began with the fall of the Han dynasty in 220 AD. Buddhism was seen as a means to unify the Empire and consolidate dynastic power, hence Sui rulers began the construction of major religious buildings and commissioned Buddhist images. While stylistically Sui sculptures continue in the tradition established in the preceding dynasties, 'characteristics that were latent in the two preceding styles were brought to full blossom by Sui carvers' (Angela F. Howard, Chinese Sculpture, New Haven, 2006, p. 290). Osvald Siren in ‘Chinese Marble Sculptures of the Transition Period’, BMFEA 1940, no. 12, p. 490, states that 'The observation of nature seems indeed to have increased as well as the mastery of the sculptural form'.

Excavations at Qingzhou, in Shandong province, have yielded Northern Qi and Sui limestone figures of bodhisattvas, with full oval faces and crowns carved with intricate diadems, pendent tassels and articulated bands. Two standing bodhisattvas from this group are illustrated in Masterpieces of Buddhist Statuary from Qingzhou City, Beijing, 1999, pp 132-134.

This head also shares similarities with a stone head from the Jingyatang Collection, included in the exhibition The Art of Contemplation – Religious Sculpture from Private Collections, National Palace Museum, Taipei, 1997, cat. no. 62, and sold in these rooms, 20th March 2018, lot 204; two standing figures illustrated in Matsubara Saburō, Chūgoku Bukkyō chōkoku shiron [Historical survey of Chinese Buddhist sculpture], Tokyo, 1995, vol. 3, pls 559 and 561; and a figure in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, illustrated in Denise Patry Leidy and Donna Strahan, Wisdom Embodied: Chinese Buddhist and Daoist Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New Haven, 2010, fig. A16. See also two standing figures attributed to the Northern Qi dynasty, in the Cincinnati Art Museum, illustrated in Ellen B. Avril, Chinese Art in the Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati, 1998, pl. 20.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F46%2F82%2F119589%2F129704536_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F02%2F19%2F119589%2F129119322_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F61%2F29%2F119589%2F129100630_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F39%2F57%2F119589%2F127899684_o.jpg)