Making Marvels: Science and Splendor at the Courts of Europe at Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

NEW YORK - Between 1550 and 1750, nearly every royal family in Europe assembled vast collections of exquisite and entertaining objects. Lavish public spending and the display of precious metals were important expressions of power, and possessing artistic and technological innovations conveyed status. In fact, advancements in art, science, and technology were often prominently showcased in elaborate court entertainments that were characteristic of the period. Opening November 25, Making Marvels: Science and Splendor at the Courts of Europe will explore the complex ways in which the wondrous objects collected and displayed by early modern European monarchs expressed these rulers’ ability to govern.

The exhibition and accompanying catalogue are made possible by the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation.

Max Hollein, Director of The Met, commented: “On a regular basis, news about the latest technological devices and their astonishing capabilities both fascinates and delights us. These familiar feelings echo those of princely patrons in centuries past who desired to possess and display the most marvelous artistic creations and inventions, made of the most precious and unusual materials and incorporating the newest scientific information.”

Exhibition curator Wolfram Koeppe continued: “The widespread and intense emotional commitment to machines and gadgets in the royal courts of Europe in the 16th through 18th century encouraged men of talent to put their energies into building the new devices for production, transportation, and communication, which are among the most distinctive features of modern life.”

The exhibition will feature approximately 170 objects—including clocks, automata, furniture, scientific instruments, jewelry, paintings, sculptures, print media, and more—from The Met collection and more than 50 lenders. A number of these works have never been displayed in the United States. Among the many exceptional loans will be silver furniture from the Esterházy Treasury; the largest flawless natural green diamond in the world, weighing 41 carats and in its original 18th-century setting; the alchemistic table bell of Emperor Rudolf II; a large wire-drawing bench made for Elector Augustus of Saxony; a rare example of an early equation clock by Jost Bürgi; and a reconstruction of a late 18th-century semi-automaton chess player, known as “The Turk,” that once famously caught Napoleon Bonaparte cheating.

Diamond hat garniture, featuring the Dresden Green Diamond, Franz Michael Diespach, Franz Michael Hueber, 1768 - 1769, Grünes Gewölbe (Green Vault), © Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden. Photographer: Jürgen Karpinski

Alchemical table bell of Emperor Rudolf II, c. 1600, Hans Bulla. © Kunsthistorisches Museum–Museumsverband

Making Marvels is the first exhibition in North America to highlight the important conjunction of art, science, and technology with entertainment and display that was essential to court culture. The exhibition will be divided into four sections dedicated to the main object types featured in these displays: precious metalwork, Kunstkammer objects, princely tools, and self-moving clockworks or automata. (Kunstkammer is the term used in German-speaking provinces to describe these collections.)

In order to emphasize the scientific and technological content of these objects, the exhibition will begin by establishing the high level of material value and artisanal quality that princes had to meet in these displays of wealth and power. Visitors will encounter a set of superbly fashioned silver furniture that was considered the ultimate symbol of power, status, and wealth during the early modern period. The second section will be dedicated to the unusual objects of the Kunstkammer. These items were typically composed of newly discovered natural materials set in finely crafted mounts of silver or gold, whose highly inventive designs often embodied the most up-to-date knowledge of the natural world. Reflective of the multi-layered objects they housed, the Kunstkammer functioned simultaneously as places of amusement, research retreats for the investigation of nature, and political showcases for magnificence.

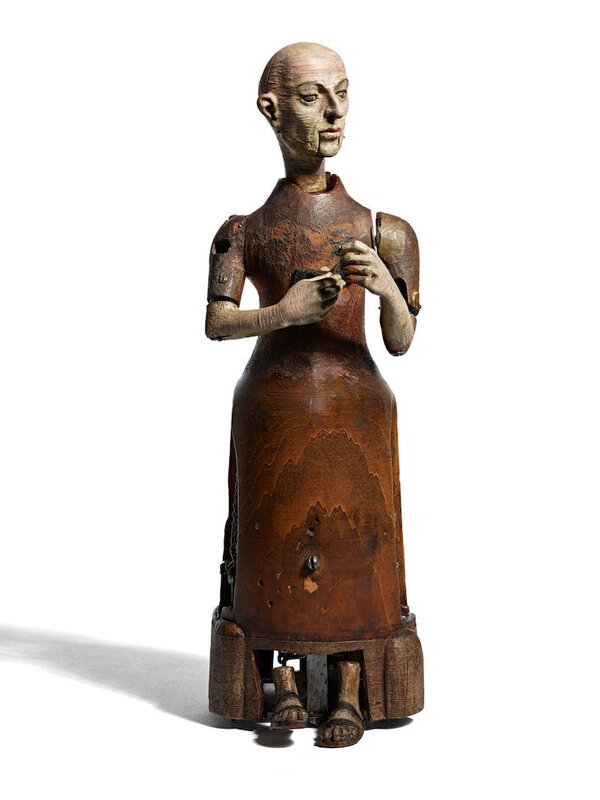

‘The Moving Monk’, c. 1550, probably Spanish, possibly circle of Juanelo Turriano. © National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

Knowledge of subjects such as natural philosophy, artisanal craftsmanship, and technology was considered tantamount to the practical wisdom, self-mastery, and moral virtue integral to successful governance. Pursuits such as metalsmithing, surveying, horology, astronomy, and turning at the lathe were part of the education and entertainment of princes in courts across Europe. The exhibition’s third section will present the scientific instruments, artisanal tools, and experimental apparatus used by rulers as they developed the technical skills so important to their princely identity.

The exhibition will conclude with innovations in mechanical technology. Self-moving clockwork machines—perhaps the best-known technological display objects—were also a rich source for allegories of rulership. Additionally, as courts competed for technical supremacy, many innovations in mechanical technology were developed at the urging of princely patrons. Automata represented the ultimate attempt to use mechanics to create life-like movement, and were extremely popular additions to princely collections from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment. One highlight will be “The Draughtsman Writer,” a late 18th-century writing automaton that inspired the book The Invention of Hugo Cabret and its movie adaptation. The advanced mechanism of this piece, which stored more information than any machines that came before it, was the forerunner of the computer, the most common technology used today.

Astronomical display clock of Otto Henry, Elector Palatine, 1554–61, Philipp Imser, with Gerhard Emmoser. © Technisches Museum, Vienna

Throughout each gallery, videos and digital models will vividly evoke the historical reality of the objects on view and emphasize the similarities between early modern objects and contemporary technological entertainments. Exhibition visitors will discover innovative marvels that engaged and delighted the senses of the past much as 21st-century technology holds our attention today—through suspense, surprise, and dramatic transformations.

Making Marvels is organized by Wolfram Koeppe, the Marina Kellen French Curator in The Met’s Department of European Sculpture and Decorative Arts.

The exhibition will be accompanied by a richly illustrated catalogue, published by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and distributed by Yale University Press ($65, hardbound), as well as a picture album ($14.95). Both will be available in The Met Store.

Wire-Drawing Bench, before 1565. Leonhard Danner (1497/1507?–1586). German, Nuremberg. Various woods, wood marquetry, iron, steel (gilded, etched). Musée National de la Renaissance, Château d'Écouen. Photo © RMN-Grand Palais (musée de la Renaissance, château d'Ecouen)

Gerhard Emmoser (German, active 1556–84). Celestial globe with clockwork, 1579. Partially gilded silver, gilded brass (case); brass, steel (movement). Overall: 10 3/4 × 8 × 7 1/2 in. (27.3 × 20.3 × 19.1 cm); Diameter of globe: 5 1/2 in. (14 cm). Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York (17.190.636) © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fountain, third quarter of the 16th century. Austrian, possibly Innsbruck. Bronze (engraved, chiseled), iron, copper, natural and dark artificial patination. © Castello del Buonconsiglio, Monumenti e Collezioni Provinciali, Trento

Green Turban Shell Cup and Cover, Johann Joachim Busch (German), ca. 1600, © Staatliches Museum Schwerin.

Automaton Clock in the Form of an Elephant, 1600–1610. German, Augsburg. Metal (gilded), bronze (silvered), copper, steel, enamel, wood (ebonized), glass, paint. Loyola University Museum of Art, Chicago, Gift of Mrs. Thomas Stamm with deep appreciation and affection in recognition of Rev. John J. Piderit, S.J., 22nd President, Loyola University Chicago, Martin D'Arcy, S.J., Collection © Loyola University Chicago

Automaton Clock in the Form of Diana on Her Chariot, ca. 1610. South German, probably Augsburg. Case: ebony, bronze (gilded); dials: silver (partially enameled); movement: iron, brass. Yale University Art Gallery, New Haven, Gift of Mrs. Laird S. Goldsborough in memory of Mr. Laird Shields Goldsborough, B.A., 1924. Courtesy Yale University Art Gallery

Joachim Friess (German, 1579–1620). Automaton in the Form of Diana and the Stag, ca. 1610–20. [German, Augsburg.] Cast and chased silver, partially gilded and painted with translucent lacquers, 13 x 9 9/16 x 10 in. (33 x 24.3 x 25.4 cm). Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Museum purchase with funds donated anonymously and the William Francis Warden Fund, Frank B. Bemis Fund, Mary S. and Edward Jackson Holmes Fund, John Lowell Gardner Fund, and by exchange from the Bequest of William A. Coolidge. © Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

Musical Clock with Spinet and Organ, Augsburg, ca. 1625, Veit Langenbucher (German, 1587–1631). Ebony, gliding, brass, silver gilt, gilt brass, iron, various wood and metals, wire, parchment and leather, 30 3/4 × 19 11/16 × 12 5/8 in. (78.1 × 50 × 32 cm); Inner Mechanism: 10 3/4 × 19 × 10 in. (27.3 × 48.3 × 25.4 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Purchase, Clara Mertens Bequest, in memory of André Mertens, 2002 (2002.323a–f) © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Watch, ca. 1670, Watchmaker: Nicolaus Rugendas the Younger (German, 1619–1694/5) , master 1662, German, Augsburg. Case and dial: painted and raised enamel on gold, set with gemstones (rubies), with a single hand; Movement: gilded brass and partly blued steel. Overall: 3 1/8 × 2 1/8 × 7/8 in. (7.9 × 5.4 × 2.2 cm); Diameter (back plate): 1 3/4 in. (4.4 cm). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Gift of J. Pierpont Morgan, 1917 (17.190.1520). © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Parade ewer and basin, ca. 1689–92. [German, Augsburg.]. Ewer by Marx Weinold (German, master 1665, died 1700). Basin by Johann Mittnacht I (German, Augsburg 1643–1727 Augsburg). Silver, partially gilt. Ewer (a): 14 3/8 × 8 1/2 × 6 in., 3 lb. (36.5 × 21.6 × 15.2 cm, 1350g); Basin (b): 2 × 25 3/16 × 22 3/8 in., 4.3 lb. (5.1 × 64 × 56.8 cm, 1966g). The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Purchase, Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Acquisitions Fund, in honor of Anna-Maria Kellen, 2014 (2014.265a, b) © The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Night Clock, Case and hardstone mosaics by Giovanni Battista Foggini (Italian, 1652 - 1725), 1704–1705, Ebony, gilt bronze, and semiprecious stones including chalcedony, jasper, lapis lazuli, and verde d'Arno, 95 × 63 × 28 cm, 25.4014 kg (37 3/8 × 24 13/16 × 11 in., 56 lb.), 97.DB.37, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles © J. Paul Getty Trust

Musical automaton clock, ca. 1777. Movement: Jan Carel Lambreghts (before 1751). Flemish, Antwerp. Metal (gilded), bronze, copper, silver, glass paste (cut), enamel. © The Al Thani Collection Foundation Limited

Mechanical Paradox, third quarter of the 18th century. Italian, Florence. Beechwood, mahogany, walnut wood, palisander, brass. © Museo Galileo–Istituto e Museo di Storia della Scienza, Florence

Henr1 Maillardet (Swiss, born 1745). The Draughtsman-Writer, ca. 1800. Brass, steel, wood, fiber. © Franklin Institute, Philadelphia.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_dcd32f_telechargement-32.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_0d4ec9_telechargement-27.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_fa9acd_telechargement-23.jpg)

/image%2F1371349%2F20240426%2Fob_9bd94f_440340918-1658263111610368-58180761217.jpg)