An extremely important and rare celadon and russet jade horse head, Han–Six Dynasties

Lot 252. An extremely important and rare celadon and russet jade horse head, Han–Six Dynasties. Height 3⅞ in., 9.7 cm. Estimate 600,000 - 800,000 USD. Lot sold 746,000 USD. © Sotheby's.

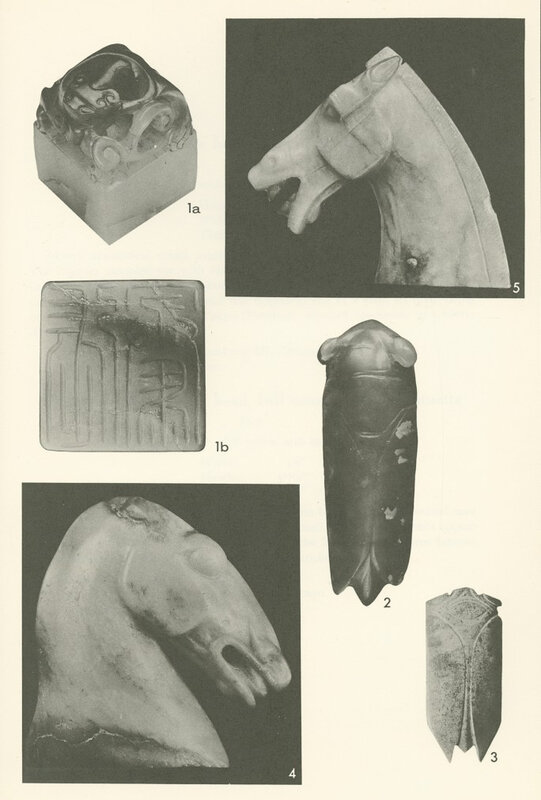

strikingly modeled in a bold and angular sculptural style, the slightly lowered head facing forward, detailed with the mouth agape revealing two rows of well-defined teeth below the flared nostrils, the long, flat nose bridle extending to triangular-shaped eyes above muscular jaws, the pair of back-swept pointed ears flanking a finely incised mane extending to the broad arched neck, pierced on each side with a small aperture connected with a metal pin, the softly polished stone of a variegated grayish-celadon color with a russet patch to the right side and some natural veins, stand (2).

The present lot illustrated In an Exhibition Of Chinese Archaic Jades, C.T. Loo, Inc., Norton Gallery Of Art, West Palm Beach, 1950, pl. LX, no. 2.

The current lot and another example, illustrated in Alfred Salmony, Chinese Jade Through the Wei Dynasty, New York, 1963, Pl. XXXII-4 and 5.

Note: Boldly sculpted with simple stylized contours that convey innate power, this jade horse head exemplifies the thriving artistic tradition of equine representations during China’s early imperial history. Throughout China’s long history, the horse has played a significant role in the expansion and consolidation of the empire, as well as a means by which to maintain contact and control across such a vast and diverse terrain. The Han dynasty was repeatedly threatened with attempts by the Xiongnu, the multi-ethnic nomadic group inhabiting the Eurasian Steppe, to raid the northern and eastern boundaries of China’s territories. This led to a search for horses that were superior to China’s own domestic breeds, and better suited to the challenging topographies of the regions. During the reign of the Wudi Emperor (141 to 87 BC), the discovery of the fabled ‘celestial’ or ‘blood-sweating’ warhorses from the lands of Ferghana (modern-day Turkmenistan) was made by an envoy to the court. These powerful steeds were not only of greater stature to those from China, but were also known for their speed, power and stamina. Significant diplomatic and, eventually, military resources were allocated to secure these breeds, and it is reputed that in 101 BC fifty such horses reached the capital.

It is against this backdrop that a thriving artistic tradition of equine sculpture began to emerge, with craftsmen capturing the vigor and power of the steed, typically conveyed through depictions of bulging eyes, flaring nostrils, muscular jowls below sharply pronounced cheek bones, and an open square jaw framed by snarled lips to expose the teeth.

Mirroring the military significance of the arrival of these horses into China, sculptures of horses or horses and riders began to appear frequently amongst the most prominent tomb goods. The largest quantity of extant examples of Han dynasty horse sculpture are preserved in ceramic. Compare two pairs of painted pottery horse and rider models which demonstrate similar physical representations to the Junkunc horse head. The first pair, excavated in 1965 near the Western Han dynasty tombs of Yangjiawan, Xianyang, Shaanxi Province, now in the Xianyang Museum, was included in the exhibition Imperial China. The Arts of the Horse in Chinese History, Kentucky Horse Park and International Museum of the Horse, Kentucky, 2000, cat. no. 121; the second pair are illustrated in Martha Blackwelder and John E. Vollmer, At the Edge of the Sky. Asian Art in the Collection of the San Antonio Museum of Art, San Antonio, 2006, pl. 4. A painted pottery head of a horse, without its neck, was included in the exhibition Relics of Ancient China from the Collection of Dr. Paul Singer, Asia House Gallery, 1965, cat. no. 133, and another, with its neck, was gifted to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, by Samuel T. Peters in 1926 (acc. no. 26.292.45).

A Pottery Model of Horse's Head, Han dynasty (206 B.C.–A.D. 220), Gift of Mrs. Samuel T. Peters, 1926. © 2000–2020 The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Far more ambitious than the pottery sculptures were those cast in bronze. One of the most iconic Han dynasty representations is the monumental (76 cm high) gilt-bronze standing horse unearthed in 1981 from a tomb east of the Maoling Mausoleum of Emperor Wudi, extensively published and most recently included in the exhibition Everlasting like the Heavens. The Cultures and Arts of the Zhou, Qin, Han, and Tang, Tsinghua University Art Museum, 2019, pl. 307; as well as the famous Eastern Han dynasty ‘galloping horse’, excavated from a tomb in Wuwei, Gansu Province in 1969, illustrated in Xiaoneng Yang (ed.), New Perspectives on China’s Past. Chinese Archaeology in the Twentieth Century, Yale, 2004, pl. 90, together with several standing bronze horses, some pulling chariots and others with riders atop, see Gan Bowen, 'Gansu Wuwei Leitai Donghanmu qingli jianbao [Brief report on the excavation of a Eastern Han tomb at Leitai, Wuwei, Gansu province], Wenwu, no. 2, Beijing, 1972, pls 5-7. Compare also an Eastern Han pair of bronze horses standing over 112 cm tall excavated in Hebei in 1981, illustrated in A Selection of the Treasures of Archaeological Finds of the People’s Republic of China, 1976-1984, Beijing, 1987, pl. 348; and another slightly larger standing example (measuring 116 cm), from the Hebei Provincial Museum, included in the exhibition Pegasus and the Heavenly Horses: Thundering Hoofs on the Silk Road, Nara National Museum, Nara, 2008, cat. no. 92. Given the perishable material, it is not surprising that only a very small number of examples preserved in wood are known. See, however, a standing horse and chariot, also excavated from a Han tomb in Wuwei, illustrated in Gansu Provincial Museum, 'Wuwei Mozuizi sanzuo Hanmu fajue jianbao [Brief report on the excavation of three Han tombs at Mozuizi, Wuwei]', Wenwu, no. 12, Beijing, 1972, pl. 4, no. 1.

Representations in jade are rare, commensurate with the scarcity and material cost of the stone. Of the complete jade horses known, most suggest a more mythical representation of a ‘heavenly horse’, for example compare two winged jade horses in the Qing Court Collection, illustrated in The Complete Collection of Treasures of the Palace Museum. Jadeware (I), Hong Kong, 1995, pls 196-7.

The existence of jade horse heads and necks (without bodies) is confirmed by an earlier example excavated in 1986 from the circa 537 BC Spring and Autumn Period tomb of Duke Qin, Fenxiang, Shaanxi Province, today housed in the Shaanxi History Museum, Xi’an. Measuring just 5.3 cm in length and minimally carved from a polished black jade, it is drilled through a tab running along the lower neck with apertures for attachment, see Everlasting like the Heavens. The Cultures and Arts of the Zhou, Qin, Han, and Tang, Tsinghua University Art Museum, 2019, pl. 225. The most famous Han dynasty example in jade is unquestionably the iconic and somewhat controversial jade horse head and chest in the Victoria and Albert Museum, acquired from the collection of George Eumorfopoulos in 1935, extensively published including in Rose Kerr (ed.), Chinese Art and Design. The T.T. Tsui Gallery of Chinese Art, London, 1991, pl. 44. Other examples traditionally attributed to the Han dynasty include: one formerly in the collection of Oscar Raphael, included in the International Exhibition of Chinese Art, Royal Academy of Arts, London, 1935, cat. no. 530; one from the Somerset de Chair Collection, illustrated in Geoffrey Wills, Jade of the East, New York, 1972, pl. 48; one also from the Junkunc Collection, illustrated alongside the present lot in Alfred Salmony, Chinese Jades Through the Wei Dynasty, New York, 1963, pl. XXXII-4; its mate in the Okura Collection, Tokyo, illustrated in Sueji Umehara, Selected Specimens of Chinese Archaic Jade, Kyoto, 1955, pl. LXVIII; and another in the Harvard Art Museums, illustrated in Hugo Munsterberg, Art of the Far East, New York, 1968, pl. 36. A larger white stone example (25 cm long) was included in the Exhibition of Chinese Art, Berlin, 1929, cat. no. 131.

The recent publication of a pair of larger (13 cm and 18 cm long) green jade horse heads without necks from the Grenville L. Winthrop Collection, now in the Harvard Art Museums, have reinvigorated the debate concerning jade horse heads attributed to this period. Collected in the early 20th century (the larger from Yamanaka & Co. in 1934 and the smaller known to have entered the collection no later than 1938, when it was published in Alfred Salmony, Carved Jade of Ancient China, Berkeley, 1938, pl. LXVII), both Winthrop heads have oval drillings to the base filled with remnants of wood, iron and steel rods. These unusual trace materials led to their revised ‘Han to Tang period (?)’ attribution when recently published in Jenny F. So, Early Chinese Jades in the Harvard Art Museums, Harvard, 2019, pls 43A-B, where the author also casts doubt over the Han dynasty attribution of this group.

Whilst the stylistic details of the Junkunc horse compare extremely closely to its excavated counterparts in pottery, bronze and wood, the absence of another jade horse head discovered from a Han dynasty tomb presents the possibility that these may have been produced in the centuries following the Han dynasty.

Sotheby's. Junkunc: Chinese Jade Carvings, New York, 22 September 2020

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F69%2F19%2F119589%2F129546631_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F79%2F86%2F119589%2F129517263_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F77%2F99%2F119589%2F128487352_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F37%2F19%2F119589%2F127869523_o.jpg)