Islamic Prayer Rugs

Prayer Rug, 1570s-1590s, Safavid, Iran, Museum of Islamic Arts, Qatar.

Most of these preserved rugs were intended as diplomatic gifts from the Safavid court to the Ottomans. The poetic inscription on the border is in nasta`liq script, in Persian verse & includes the name of Sultan Murad.

Prayer Rug, 16th century, Turkey, Walters Art Museum.

This Ottoman rug depicts a floral pattern. While the central arch has no columns to reflect the prayer niche, the arrangement of the blossom pattern is a kind of floral translation of the architecture.

Prayer Rug, 16th century, India. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This weaving is part of a group that uses the most popular motif of the emperor Shah Jahan’s reign: the single flowering plant, in this case a poppy, set within a niche.

Prayer Rug, late 16th century, Istanbul, Turkey. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Ottoman workshops produced a great variety of carpet designs that usually employed a group of familiar elements, consisting of naturalistic flowers, lotuses, and palmettes, often combined with arabesques.

Prayer Rug, 16th century, Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Identified by its central niche design, the Qur’anic inscriptions in its border & names of God in its spandrels, relates to a group of rugs which were a diplomatic gift from Safavid Shah ‘Abbas I to Ottoman sultan Murad III.

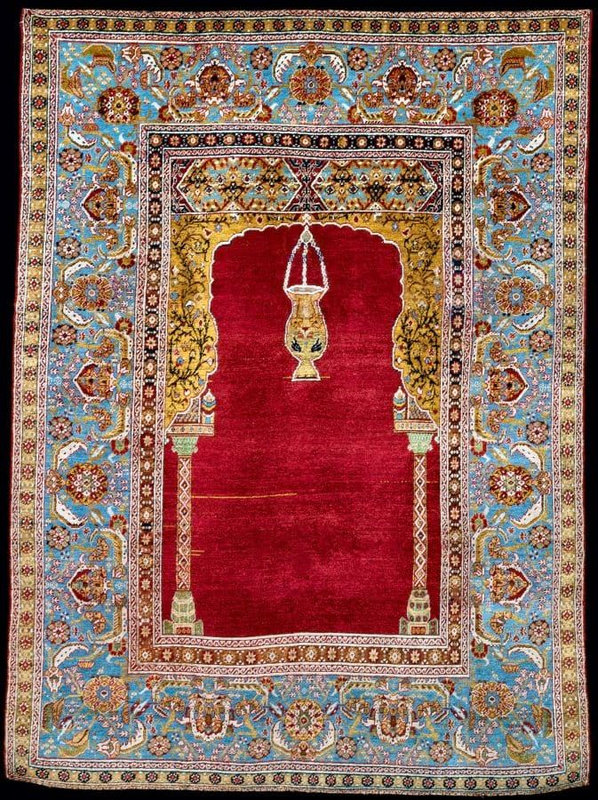

Prayer Rug, late 16th or early 17th century, Istanbul, Turkey, or Ottoman Cairo, Egypt, The Khalili Collections, London.

With a central niche is in the form of a mihrab, with decorative side-columns & a hanging mosque lamp & was hung on a wall, to serve as a mihrab for communal prayers.

Prayer Rug, Early 18th century, Kashmir. Harvard Museums.

Prayer carpet, Indian or Mughal, in so-called Millefleurs design; a vase with a single stem bearing multiple blossoms between two cypress trees.

Prayer Rug, 18th century, Turkey, Museum of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities, Stockholm, Sweden.

This rug belongs to the group of prayer rugs from Ghiordes, a village between Izmir and Ushak, where most of the Anatolian prayer rugs were manufactured in the 18th–19th centuries.

Prayer Rug, 18th century, Kula, Manisa province, Anatolia, Turkey, Asia, Saint Louis Art Museum.

Prayer rugs often feature a mihrab, or arched niche. This carpet is distinctive for its pairs of slender columns, a characteristic of Nasrid architecture from Muslim Spain.

Prayer Rug, late 18th–early 19th century, Mudjar, Anatolia, Turkey, Saint Louis Art Museum.

Includes a less common depiction of stylized water pitchers in the green areas above the arch which may refer to ritual ablution, which is required of Muslims before performing prayer.

Prayer Rug, late 18th–early 19th century, Gördes, Anatolia, Turkey, Saint Louis Art Museum.

Traditionally prayer rugs feature an arched niche representing the mihrab of the mosque. This architectural element orients worshippers towards the holy city of Mecca during prayer.

Prayer Rug, 19th century, Turkey, The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, Washington DC, USA.

During their daily prayers, Muslims traditionally roll out small rugs to cover the ground, creating a ritually clean space for their devotions. Made using traditional techniques: knotted pile; symmetrical knot.

Prayer Rug, 19th century, Iran. Image courtesy Christie's

For believers in Islam, a rug is more than just a mat for praying; the rug’s design incorporates important Islamic symbols. This rug features the mihrab and depicts the gardens of paradise.

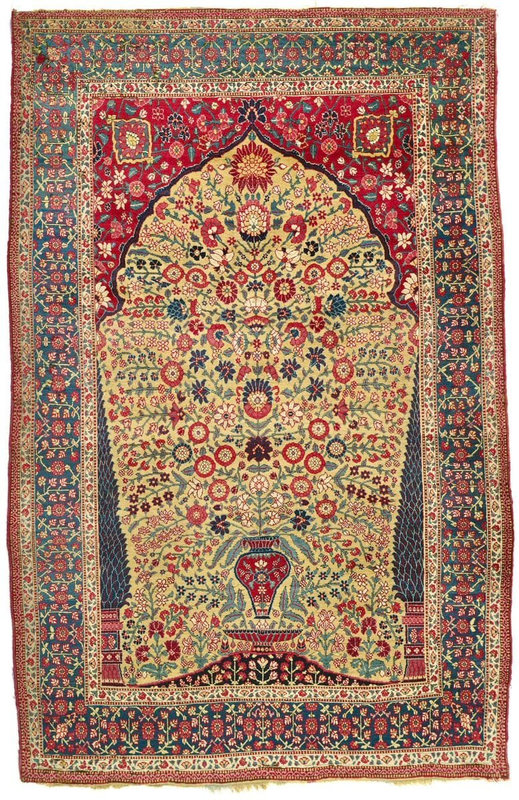

A Sarouk Fereghan prayer rug, North Persia. Circa 1890. Courtesy Sotheby's.

In rugs woven with the tree of life or with flowering vases the architectural nature of the mihrab is sometimes emphasized by thin columns flanking the central motif, as it is in the present lot.

Prayer Rug, 19th century, Iran. Courtesy Christie's

A silk kasha’s rug. The elegant niche suggests that this was a prayer rug, to be hung on a wall in the direction of Mecca, however, and not spread on the ground.

/https%3A%2F%2Fprofilepics.canalblog.com%2Fprofilepics%2F1%2F0%2F100183.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F03%2F02%2F119589%2F96711876_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F11%2F31%2F119589%2F94773502_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F20%2F83%2F119589%2F94772815_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F26%2F72%2F119589%2F75604929_o.jpg)

/https%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F59%2F60%2F119589%2F26458628_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F00%2F00%2F119589%2F129758935_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F29%2F28%2F119589%2F129637299_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F88%2F37%2F119589%2F129631480_o.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fstorage.canalblog.com%2F77%2F79%2F119589%2F129631259_o.jpg)